Magazine

When My Father Calls

Sometimes peanuts and patience can help a heart mend. Such was the case when Everdeen, a tiny chipmunk, came into my father’s life.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Robert Crawford

—

When I was 8 or so, my father found a mouse nest in one of the air vents of my mother’s maroon Subaru. The tiny rodents were the size of chess pawns, all bald and pink, with their eyes closed. “They won’t survive if we move them,” he told me as I peered into the cavity. “They’re too young to disrupt their natural environment at this stage in their development.” My mother, standing beside me, pierced him with a look as though he’d scarred my innocence. “But we can try,” she said, pulling her blue fleece bathrobe tighter around her waist. “Come on, let’s go get a tissue box and make them a cozy little nest and find a bottle cap to put some water in so they can drink.” “But they’ll die,” I said, looking at my dad. “They won’t survive in here, though,” my dad said as he redirected my attention to the mice. “I bet you never thought mice would nest in a car.” My mother was already inside, rummaging for a suitable home in which to raise the litter into strong mice. She was likely thinking of what to name each of them or boiling oatmeal to hand-feed the tiny creatures. The mice died, of course, but not before my father had gently lifted the nest from the dashboard and into the small Tupperware container my mother had lined with soft dishtowels and strips of Puffs tissues.—

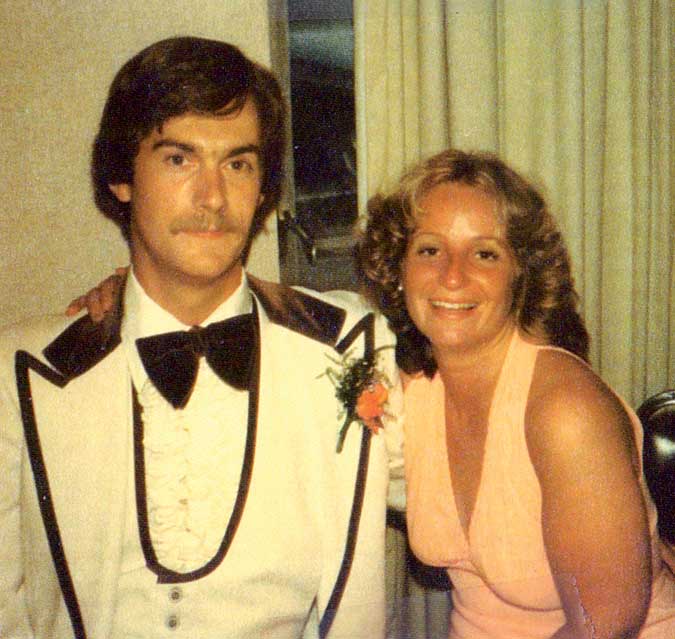

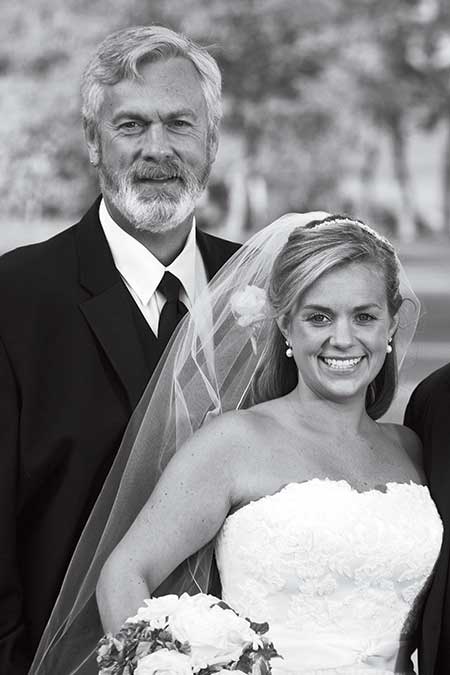

For a few years before my mother died, my grandmother lived with us. In the mornings, before filling out my father’s crossword puzzle, my grandmother would stare out the window, watching the squirrels and chipmunks quarrel over the corn my father had thrown for them and listening to the nasal calls of the nuthatches. After a few months of this, she named one of the chipmunks that she saw regularly: “Tippy,” because he had only half a tail. My father joked, only to me, about how there were hundreds of Tippys—a breed, or family, whose tails were cut short. It was when she started calling the chipmunk by different names that we realized that her memory loss was dementia. And then, when my grandmother forgot to take her insulin one too many times, my father promised her that there would be chipmunks at the nursing home. My dad never took to Tippy because he spent most of his time taking care of my mother after my grandmother had moved out. For the six months that hospice helped us nurse her, my father arranged for a hospital bed to be put in the family room, where my mom could look out the sliding glass door and onto the patio. He staged garden gnomes and ceramic hedgehogs throughout the annual garden because he knew that she loved to imagine they were real. He put out birdfeeders so that she could watch the chickadees, her favorite, and he baited Tippy with ears of dry corn that he hung from a shepherd’s hook. He would sit with my mother in the mornings after he brought her coffee with cream and two Splendas. He would hold her hand while she dozed and think of other ways he could make her happy. The day I told my father, two years later, that I was going to move in with the man who would become my husband, his eyes welled with tears. “The house will be so different without estrogen,” he said. “Even though you’re going to get married, you’ll still be my little girl, right?” It was after I married that my father adopted Everdeen. He would watch her gnaw on the sunflower seeds that had spilled from his carefully placed birdfeeders. He watched her patterns, replicating the sound of sunflower seeds falling from the feeder in order to lure her to the patio, where he’d toss a few seeds at a time. Two weeks later she was eating out of his hand.

—

One of Everdeen’s kin had babies the next spring, my father told me the day we sat on the patio: “You cannot believe how cute they are. Not as cute as Everdeen, but still cute.” “How do you know they’re related to Everdeen?” I handed him another peanut out of the jar. “Because that’s what Mom would say.” We both laughed. “No, I know because Everdeen and her kinfolk all exit the same series of tunnels. They wouldn’t allow other chipmunks in their territory.” He set the sapling he was whittling against the glass table and sipped from his Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi. “Hand me the sandpaper, will you?” And then, “You know, I’m ready for a grandbaby.” My dad refers to her—my as-yet-not-conceived child—by her name: Caroline. He talks about how she’ll be a country girl; he’ll buy her a pony, and even if it’s blind in one eye the way mine was, she’ll ride it like the wind. And, of course, she’ll love visiting him, because where else can you feed a chipmunk out of your hand? “I’ll teach little Caroline that it takes time,” he said, lifting his white handkerchief to wipe the sweat from his brow. “To train a chipmunk, that is.” “What if I have a boy?” “Boys can train chipmunks, too,” he said. “And it’s worth the time it takes, because they keep coming back.”—

It occurred to me one day that Everdeen might not be a female; the Peterson field guide my father gave me for my 24th birthday says that you have to hold a chipmunk upside down and look at the bumps under its tail to determine its sex. I decided not to ask him why he thinks Everdeen is an Everdeen, after he drove two hours south one Sunday just to eat omelets with me and tell me about how he’d successfully made her jump for a nut the previous week. He’s always known the things that I have to ask: Clydesdale or Percheron? Poison ivy or Virginia creeper? Beech or aspen? Male or female? “It’s endless entertainment for Gram,” he called to tell me after he’d gotten home from breakfast. “She just plops down on the patio, feeds Everdeen, and is as happy as a clam.” I reminded him of the photo he had on his computer, showing that Everdeen doesn’t run now—that she’ll sit on her hindquarters shelling the peanuts, tucking away the fruit and starting over again after depositing her stash in the hole. We laughed the way you laugh when there’s nothing else to do.

I enjoyed this story very much for several personal reasons, nice read to start my day, thank you. Now I gotta run, my Chickadees are waiting for me to hand feed them on the deck.

A great story to read ….well crafted, skillful and put together. You will enjoy…..

Emily is the most talented writer. This is a perfect example of her innate ability to create a vivid image in the readers mind that evokes an intimate response, regardless of the readers connection to her. Outstanding piece! Get your autographs now…

So happy to see this on-line. What a sweet piece. I read everything that Emily writes!

Beautifully written Emily….makes me homesick for New England! Have not been able to find the Magazine here in Texas since I heard you were featured in it. Keep writing you have a wonderful gift!

This essay was fantastic, Tender and real and beautifully written. I hope to see more from this writer.

Just reread your story and it resounds within as I am a father and grandfather. Thank you Emily.

My dad also trained chipmunks in Maine to eat from his hand. When my children were little, they would also eat out of their hands, they were thrilled. We called ours Chippy.