I gave Henry his first bike as a pre-birthday present, thinking that early November might be too late in the season to get him going. I needn’t have worried. The teaching-him-to-ride part was a snap. He simply assumed he could ride from determined viewings of Rad, an ’80s teen bike-racing film that he and I watched again and again. Henry hopped aboard that little fire-engine-red BMX-style bike, with its cool upsweeping handlebars and tiny six-inch wheels, and gave me a look that said,

What’s been keeping you so long? He was three.

That was then; this is now: We’re at the start line of the New England Regional Cyclocross Championship, among a field of 36 riders, on a cold, mid-December morning in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. We’re on bikes–the familiar part. But we’re racing against each other–the unfamiliar part. Henry is 15; his bike is a white Jamis with 18 gears and a sleek Italian-made racing seat. As father and son we’ve never raced against each other in anything. “You ready?” asks Henry.

I know what you’re thinking: that this is a story about a father and son jockeying to be top dog. Adolescence veers into adulthood and family fireworks erupt. I remember when I first knew I’d really beaten my dad in anything–in our case, singles tennis. Up until then, I was either furious at him for letting me win or furious at him for making me lose. On the day I finally won fair and square, I knew I’d probably never lose to him again.

I was pretty sure this bike race was not one of

those moments. When Henry asked, “Hey, Dad, do you want to race with me?” his invitation was more cerebral, more exploratory. After all the youth-sports years of me on the sidelines cheering him on, he’d arrived at an attractive idea: What if we competed together?

I’m not sure whether it was the crazy nature of these extreme “championships” or my worry about keeping up, but racing side by side with Henry made me very nervous. It occurred to me that at the exact time when a wise father might have coaxed his son to join him for a memorable rite of passage–say, a winter camping ordeal in the Whites–the storyline was reversed. The passage looked to be mine.

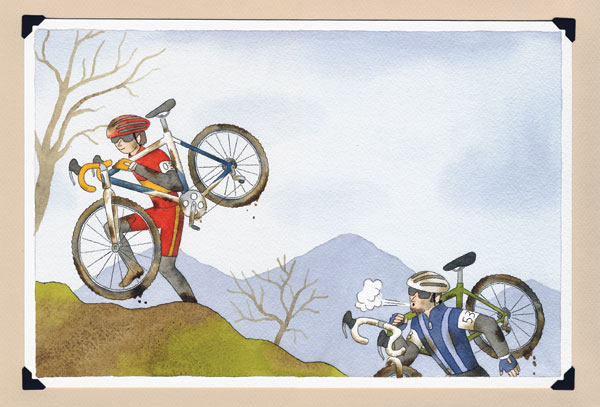

Soon after Henry learned to ride (I can’t really say I taught him), he began hurling himself and his mini-bike off roughly constructed backyard ramps. He wore his version of a Tour de France cyclist’s uniform: swim goggles and a red one-piece Power Rangers crime-fighting suit. He was still in preschool when he wrote on a Father’s Day poster that what he liked about me was riding up and down “whoop-de-dos” together. His doodle drawing depicting us on bikes wouldn’t make sense to others, but it did to me: He was riding in Power Rangers red, of course; I was in blue.

We did our fair share of whoop-de-dos for a few more years, Henry won a couple of local kids’ races, and then he discovered soccer. He grew out his hair to look like a South American star and collected imported English “footie” magazines. His coach was a wildly charismatic Jamaican who pinwheeled into bicycle kicks like Pele. Henry dreamed of playing abroad, and for a time was researching, and relaying to us, his very affordable finds in the West London real-estate market. The bike disappeared into a dark corner of the barn.

But we didn’t get to London. He was good enough to contend for a spot on the junior national team, but others were the ones who got the invites to the special trips abroad. I got the feeling Henry was coming to an understanding and was recalibrating his future. He didn’t say any of this, but I could tell something was up–and I was crushed. I’d fallen in love with his love.

Last summer I was still wondering how to rekindle his hopes and dreams when he began peppering me with questions about his first love. “Why didn’t I stick with racing?” he wondered. I noticed him watching YouTube videos of mobbed, cowbell-clanging Belgian World Cup races and inspecting blogs of top New England riders. He started talking about “bunny-hopping” things. Something was up.

Cyclocross isn’t a standard undertaking–and not just because it’s a series of bicycle races held exclusively in fall and winter. (Obsessed French and Belgian professionals originated the sport as an off-season cross-training alternative.) The lap course’s design is like a steeplechase, with hurdles to leap over, icy ladder-steep climbs to trudge up, and sandpits to plow through. Most of the time you’re on the bike, but the hurdles and run-ups require “flying dismounts,” which is exactly as treacherous as it sounds. With sprint-style races 30 to 60 minutes long, the cardiovascular demands are fierce.

But there’s also a free-spirited ethic at the core of the sport–the all-for-one, one-for-all spirit of folks who know that they’re doing something few others dare to. A midrace fall is greeted with “You okay?” from a rival. Maybe having been through the grind of highly competitive youth soccer, Henry might’ve been simply thinking, “Looks like fun.”

I wasn’t sure it was something I needed, however, and I steered clear of Henry’s first races in October. A part of me rationalized that this was Henry’s thing–stay out of it. A part of me thought it looked scary. And a part of me, not as emotionally agile as my 15-year-old son, was still consumed by the soccer-prodigy episode. Call it selfish, but I knew the immersion that was coming. He’d soon be teaching himself Flemish. I wasn’t sure I was ready yet.

I delivered Henry to the bike-shop owner at 5 a.m. on a Saturday in front of his store in Beverly, Massachusetts. Henry’s age category raced at 8 a.m. in a faraway place at the other end of the state. With a biting coastal wind whipping down Cabot Street, even Marc Bavineau, a former racer himself, looked at me and said, “Are we really doing this?”

But Henry was all in. He did well that day and had fun. He loved it, he said, phoning me to describe the course in surgical detail, especially the part where he accelerated up a launch ramp and sailed over a set of railroad ties. Could he sign up for the next one?

He set up a noisy indoor bike trainer upstairs, and before first light rode 10 miles before school. On weekends, he asked me if I wanted to join him. Henry seemed careful not to make me feel as though I needed to go with him–“If you have other things to do, no problem, Dad,” he said–but I began to understand that he might actually want his “whoop-de-do” partner again. Soccer had been different. It was all him; all me watching him. Cycling was somehow

us–and had been from the beginning.

We first went to Gordon College, a private college in nearby Wenham with a nice combination of campus terrain and fast forest roads. Henry had his team-issue 2010 bike, me an ultralight 1970s Raleigh I’d reclaimed from the curb years ago and restored. Now the rust had returned–an apt metaphor for my racing condition–but it still possessed a glimmer of its former panache.

In the shadow of the chapel’s white steeple and the red-brick library, we did loops of the quad’s fields and used long aluminum soccer benches as hurdles. The idea was to approach fast, jump off our bikes at full gallop, and shoulder them as we leapt up and over.

“I want to bunny-hop them,” Henry said. “Can I?” A bunny hop is an advanced, highly risky move, and in my “Not yet–okay” plea I wondered whether I was being sage or stifling. Allowing a three-year-old to ride or a teen to fly was fraught with exactly the same fatherly recrimination: reluctance to let go.

The next weekend we added the narrow paved roads from our house to Gordon, a five-mile warm-up in 25-degree cold. We started quietly, both of us trying to ignore the stinging discomfort in our hands, feet, and faces. We warmed just before Gordon, and from that time on, we rode as if we’d been granted a wish. A planned 45-minute ride expanded to two hours. We linked more trails together to create our own timed woods-to-road-to-pond circuit. We talked about recording our times, then charting them, to compare our improvement as the weeks passed. Actually, no, that was me.

Henry was soon “bunny-hopping” over blown-down limbs on the trails and speedily remounting like a pro. When the knotty roots hiding beneath maple and beech leaves loosened my bike’s old fork and made continuing impossible, Henry kept going, completing another lap. I waited for him by the pond, and waited, and waited some more. He should’ve been back by now, and when he finally returned, his leg was bleeding. “I might’ve hit a tree,” he pointed out. “Think the bike’s going to be okay?”

The season was almost over. He was really flying now, and he signed up for the last race at Fitchburg. I said I’d do it if I could find a dependable bike. The bike shop owner, Marc, perhaps sensing that I needed a nudge, proffered his own. I registered online hours before the deadline.

“Really!?” exclaimed Henry, when I told him I was in. “Really?” Before I could get a low-expectations word in, Henry was game-planning for the race, putting together tactics, and promising to sacrifice his well-earned position near the front of the mass start to join his first-timer dad in the back. It wasn’t that he needed to look after me, he assured me, but together we might be something special. I had the feeling he was imagining the cycling equivalent of Manny and Big Papi. I got nervous all over again.

The week before the race I rode almost every day, and when not riding, I was thinking about it. To acclimate myself to the cold, I went out mountain-biking in 20-degree weather. The next day I “crossed” in the woods. On Saturday Henry and I went out together; he was pushing me now, on the road, in the woods. The day ended with both of us tearing around the local park–using the steep slopes to practice carrying our bikes uphill, then gleefully bombing down. Evidently I bombed down a little too hard. “I think your tire is flat,” Henry informed me gently. “I hope that doesn’t happen to us tomorrow.”

On race day, we woke at 6:00 and were on the road 20 minutes later. I fixated on the dashboard thermometer, wincing when it crashed into the teens. Meanwhile, the few cars on the road featured ski racks and drivers wearing parkas. I pointed this out to Henry. He raised his clenched fist to mine for a bump:

“This is what we do,” he intoned.

The Fitchburg course, defined by orange plastic fencing, rolled across a long, low city park. As we tested the course before the start, we reached its signature feature, “the Flyover”: a 10-foot-high pyramid with steeply ascending and descending ramps. Slats were nailed into the “up” side as footholds, and a race volunteer was using a leaf blower on the green faux carpeting to melt a tongue of ice.

When the gun went off, there were 36 in our men’s Category 4 grouping, the bike-race division for the least-experienced riders. Henry dressed in shades, black tights, and a Centraal Cycle team-issue jersey. I was wearing underlayers and a blue Team Gloucester running jersey. On its front was the image of a big fat cod.

The plan was for us to ride in close proximity so we could encourage each other and help if we got into trouble. Unfortunately, I made the “rookie” mistake of trying to be safe at the start instead of blasting off.

Safe in racing equals

slow. Henry was gone before I knew it. A few minutes into the first lap, I realized with some horror that I was last. After the guy in front of me lost control of his bike in the volleyball pit and pitched into a steel fence, I was next to last.

Then a funny thing happened: I picked off a few riders. I survived the Flyover and even passed a team-affiliated racer at the hurdles–getting an “Attaboy!” from a course marshal. During the easier stretches on flat pavement I made myself shift to a bigger gear to gain more ground. I was racing now.

Then it was the last lap, and I finally saw Henry. Because the course doubled back on itself, two riders could be far apart in terms of time but still be in close physical proximity. So it was with the two of us. I was heading toward the parking-lot side of the course and a series of winding corrals, while he was en route to the finish, only the hurdles between himself and the end. I gave him a “Good job, Henry!” He beamed and flashed a thumb’s-up.

Minutes later we were both at the finish, and I was on a bubbly, chitchatty high, something that even I was a bit surprised by. I’d finished 29th out of 36 starters, about two minutes behind my son. He now knew that his dad was a lot like him–only slower. I’d failed to be his true racing partner, but in the panting high of the finish line I didn’t feel unworthy, or that I might not one fine day be the sidekick he was looking for.

A few minutes later, we got into the car and cranked the heat. We’d been in a race almost halfway across the state, and it wasn’t even 9:30 yet. As we pulled out of the parking lot, Henry looked my way and said, “Thanks, Dad–but what do you say we do

all the races next year?” I said, “Yeah, that’d be great.” What I didn’t say was that if he wanted to learn Flemish and bunny-hop a soccer bench, I was okay with that, too.