New England Boiled Wool Mittens | Yankee Classic

The art of knitting boiled wool mittens, the top choice of fishermen, was highlighted (with instructions!) in this Yankee feature from 1983.

Boiled wool mittens pattern directions.

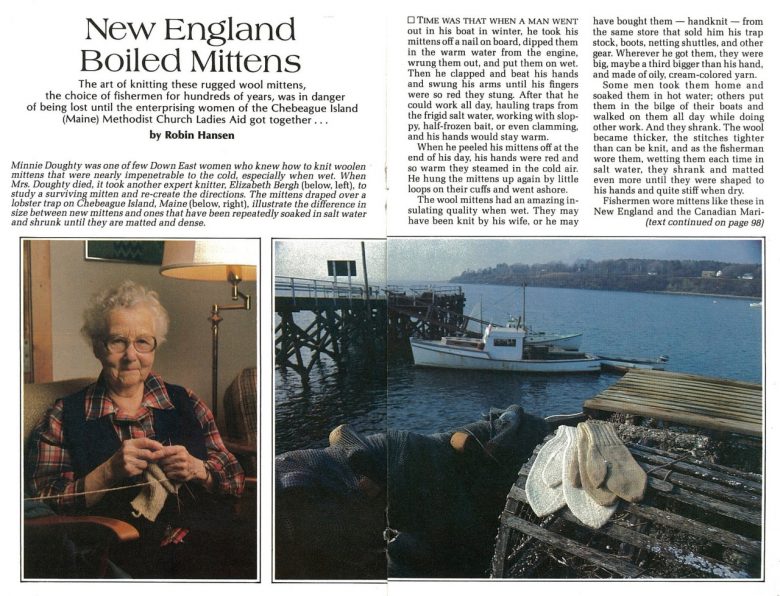

Photo Credit : Yankee Magazine/February 1983The art of knitting rugged boiled wool mittens, the choice of fishermen for hundreds of years, was in danger of being lost. That is, until the enterprising women of the Chebeague Island Methodist Church Ladies Aid in Maine got together…

Photo Credit : Yankee Magazine/February 1983

Time was that when a man went out in his boat in winter, he took his wool mittens off a nail on board, dipped them in the warm water from the engine, wrung them out, and put them on wet. Then he clapped and beat his hands and swung his arms until his fingers were so red they stung. After that he could work all day, hauling traps from the frigid salt water, working with sloppy, half-frozen bait, or even clamming, and his hands would stay warm.

When he peeled his mittens off at the end of his day, his hands were red and so warm they steamed in the cold air. He hung the mittens up again by little loops on their cuffs and went ashore.

The boiled wool mittens had an amazing insulating quality when wet. They may have been knit by his wife, or he may have bought them — handknit — from the same store that sold him his trap stock, boots, netting shuttles, and other gear. Wherever he got them, they were big, maybe a third bigger than his hand, and made of oily, cream-colored yarn. Some men took them home and soaked them in hot water; others put them in the bilge of their boats and walked on them all day while doing other work. And they shrank. The wool became thicker, the stitches tighter than can be knit, and as the fisherman wore them, wetting them each time in salt water, they shrank and matted even more until they were shaped to his hands and quite stiff when dry.

Fishermen wore mittens like these in New England and the Canadian Maritime Provinces for hundreds of years. Some still do, when they can get them.

The downfall of the fishermen’s boiled wool mittens came with the rise of the insulated glove, which on the surface sounds a lot more reasonable. Bulky and rubbery, the insulated glove is warm enough, but doesn’t permit much fine finger movement or any feeling through its layers. Some fishermen use them only for the prickly work of handling bait, complaining that they “can’t work in them.”

In many fishing communities, the art of knitting fishermen’s mittens has been lost, and even those women who wanted to knit them for their husbands couldn’t. There were no mittens left to measure, and no women left who knew how to make them.

This was the case on Chebeague Island, off Portland, until a few years ago. Minnie Doughty, the one woman who had maintained the skill, died, taking her knowledge with her. Like many other coastal women, Mrs. Doughty had had a difficult life and had lost several of her six sons to the sea. In her lifetime she had knitted a great many pairs of fishermen’s mittens — so many that when she died, the single remaining new pair was treasured as a keepsake by her daughters.

One of the expert knitters of the Chebeague Island Methodist Church Ladies Aid, Elizabeth Bergh, took these old mittens, counted stitches, measured, found a loose end to determine the thickness of the yarn, and put together instructions for fishermen’s mittens. The Ladies Aid knitters tried out the instructions, then continued knitting until they had a small pile of mittens. They “sold like hotcakes” at their fair, Miss Bergh recalled.

If you have a fisherman in the family, or if you spend much of the winter by the sea, try knitting a pair of these remarkably warm, thick, almost water-repellent mittens for someone in your family.

Here are Elizabeth Bergh’s instructions, based on Minnie Doughty’s mittens. They are probably the only instructions in print anywhere for this kind of mitten. But beware! They make a huge mitten that must be shrunk in salt water, and really can be used only in the traditional way.

The yarn traditionally used for these mittens on Chebeague Island is cream-colored, 3-ply natural Fisherman Yarn from Bartlett yarns in Harmony, Maine. This is half again as heavy as worsted weight yarn and makes an astoundingly dense mitten. Some women use Bartlett yarns 2-ply Fisherman Yarn, a worsted-weight, oiled, wool yarn, which is easier to knit and makes a lighter, more flexible mitten. The pattern is the same for the two weights of yarn. Any oiled fisherman yarn in these weights can be substituted for the Bartlett yarns Fisherman Yarn.

Instructions are for a man’s medium-sized mitten. To knit a child’s size, find a mitten pattern for worsted-weight yarn and knit a full size larger—for example, a size eight for a six-year-old—then shrink the mittens. Wool mittens shrink anyway, but few patterns take this into account.

BOILED WOOL MITTEN PATTERN DIRECTIONS

Yarn: Two skeins Bartlett yarns, 2- or 3-ply fisherman yarn, or other worsted-weight wool with lanolin, used singly.

Equipment: Four number 4 double-pointed needles, or size needed to knit correct gauge.

Gauge: Five stitches equal one inch.

On size four double-pointed needles, cast on 12, 15, and 15 stitches, a total of 42 stitches on three needles. Knit two, purl one until wristband measures four inches.

Then, first round: place last purl stitch on first needle. Purl one, knit two, purl one. Knit rest of round, increasing two stitches on each needle for a total of 48 stitches.

Second round: start thumb gore. Purl one, increasing one stitch in each of the next two stitches, purl one. Knit around, and knit rounds three, four, and five, maintaining the two purl stitches as a marker.

Sixth round: purl one, increase in the next stitch, knit two, increase in the next stitch, purl one (eight stitches, including two purls). Knit around. Knit three more rounds.

Continue to increase this way every fourth row until you have 14 stitches for the thumb gore, including the two purl stitches. Knit three more rounds and place the 14 stitches on a string.

Cast on 10 stitches to bridge the gap and divide the stitches 18 to a needle (total 54 stitches). Knit up 4 to 4-1/2 inches from thumb for the hand.

Begin decreasing in next round:

Knit two together, knit seven. Repeat around. Knit two rounds. Knit two together, knit six, and repeat around. Knit two rounds. Knit two together, knit five, and repeat around. Knit two rounds. Knit two together, knit four, and repeat around. Knit one round. Knit two together, knit three, and repeat around. Knit one round. Knit two together around. Break the yarn and draw up the remaining stitches on the tail, using a yarn needle. Darn the tail back and forth across the tip of the mitten. Thumb: Pick up from thumb gore seven stitches on each of two needles and one stitch from each side of the thumbhole, a total of 16 stitches on two needles. Pick up the 10 stitches from the palm side of the thumbhole on a third needle. Knit two rounds. Next round, decrease one stitch on each end of the third needle. There are now eight stitches on each needle. Knit 2 to 2-1/2 inches.

Next round, decrease: knit two together, knit two, and repeat around. Knit one round. Next round, knit two together, knit one, and repeat around. Break yarn and draw up remaining stitches on the tall, using a yarn needle. Darn the end into the tip of the thumb. Work all other loose ends into the fabric of the mitten.

Crochet a loop at the edge of the cuff for hanging the mitten to dry. Use the tail left from casting on, if possible. To shrink: soak the mittens in boiling hot water, squeeze them out and dry them on a radiator. I shrink mine in the drier on the hot setting, but this takes out some of the oil. Some men say to dry them in the freezer. This takes a long, long time. Some claim they soak their mittens in fish gore, then wash them in hot water. However you choose to shrink your mittens, the first shrinking will not complete the trick, but the mittens will continue to shrink in use. Don’t give up.