The Man Who Writes Nightmares | Yankee Classic

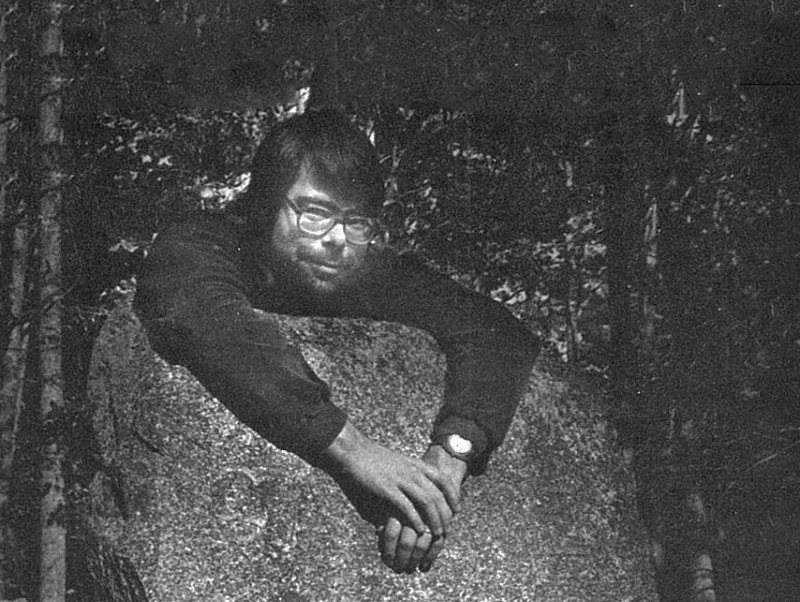

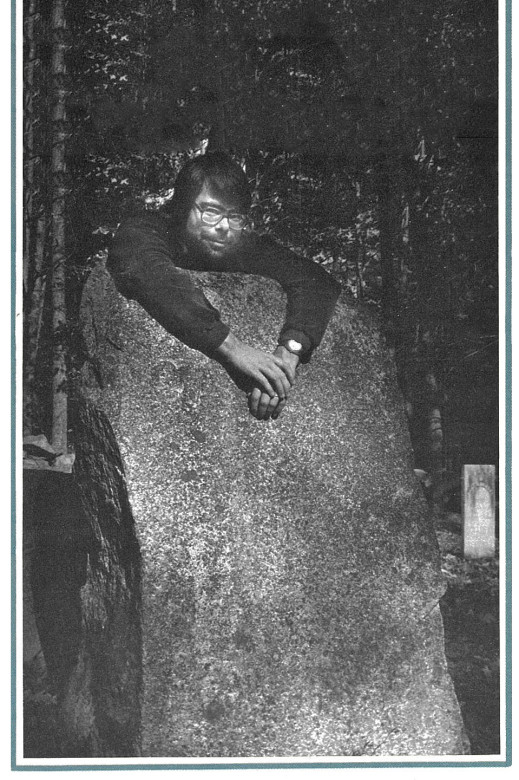

We take a look back at our March of 1979 interview with legendary Maine author Stephen King in this Yankee Classic.

HEAR HOW THE STORY HAPPENED:

Photo Credit : Carole Allen

Stephen King’s novels of terror are enjoying tremendous popularity right now, a fact which perhaps brings the Maine native more notoriety than he wants. But there is no way he could ever stop writing, because he is obsessed with the macabre, the horrific, and the demonic. It’s a marketable obsession, he’s quick to point out. “But there are madmen and women the world over who are not so lucky.”

“At night, when I go to bed, I still am at pains to be sure that my legs are under the blankets after the lights go out. I’m not a child anymore but … I don’t like to sleep with one leg sticking out. Because if a cool hand ever reached out from under the bed and grasped my ankle, I might scream. Yes, I might scream to wake the dead. … The thing under my bed waiting to grab my ankle isn’t real. I know that, and I also know that if I’m careful to keep my foot under the covers, it will never be able to grab my ankle.”

–Stephen King

The tall man is leaning against his Scout, grappling with a handful of 800-page books and a pen, with hands that are slow to unlimber from the cold. The wind whips across the parking lot of the supermarket and finds the man where he stands pinned to his car in the school parking lot, writing inscriptions inside the books with the cautious rapidity of a man who wants to say something well, but who is getting colder by the minute.

His denim jacket is badly frayed, and there are holes in the sleeves. Years before, as a student at the University of Maine-Orono, his courtship with Tabitha Spruce, daughter of the owners of a Maine general store in nearby Milford, nearly stumbled on his personal dress code. Once, as a high-school student in Lisbon, Maine, he was preening in front of a full-length mirror, trying to look like his friends. His mother, a tall, thin, but powerful woman who bequeathed her son her Irish blue eyes, threw him against a wall. “Inside our clothes, we all stand naked,” she thundered.“Don’t ever forget it.”

His shirt flaps loose in the back and he wants to tuck it back into his jeans, but that would mean putting the books on the ground, so he finishes his business with the pen and walks quickly past the football field into a side door of the school.

The name of the school is Hampden Academy. It is a small public school despite its highbrow name, located in Hampden, Maine, across the Penobscot River from Bangor. He knows his way around, he thinks, until he opens the door of what he remembers to be the teachers’ room, and finds a startled photography student hanging prints to dry in the school’s darkroom.

***

“I won’t walk under ladders. I won’t light three on a match. I’ve offended people by blowing out cigarette lighters and lighting my own cigarette. These things are handed down and handed down, and people willfully ignore this fact. I’ve never had a night that I can remember when I haven’t checked all the kids before I went to bed, when I haven’t thought that if I don’t check the kids at night the trolls and boogies will know. And I don ‘t believe it. I don’t believe I’ll have bad luck if I walk under a ladder, anymore than I believe someone in my family will die if a crow or black cat crosses my path. But I mean: why take chances with that stuff!” –Stephen King

***

The tall man is confused and runs a hand through his thick black hair that hangs to his left eyebrow, as it always has, except when it’s groomed by an expensive hairdresser for publicity photographs. The student stares at the intruder, knowing he has seen that face somewhere. It is a striking face, with or without the dark beard that appears and disappears each year like autumn foliage. After writing ‘Salem’s Lot, the novel about vampires ravaging a small Maine town that increased his already considerable fame and fortune two-fold, the man remarked ruefully that unlike his vampires, he, “unfortunately, could still see himself in the mirror.”

He opens more doors, sees familiar faces, smiles, says hello, and by trial and error finds the teachers’ room that by 12:45 is deserted. A place for a quick smoke. He has smoked since he was 18, and now, at 31, says he’s trying to quit, as he said the year before, and the year before that. He fights his personal demons one by one, he says, and this one clings to him like quicksand.

Others have described him as hyperkinetic and he roams the small room restlessly, taking in the titles of the paperbacks used in the English courses. He picks up a well-worn copy of ‘Salem’s Lot. It is a cover that created a sensation a few years ago with its single drop of crimson drooling from the icy blue lips of a child.

The bell rings. In the rapid scuffling of feet past the door he looks up to greet his friend Everett McCutcheon, head of the English Department. “Are you ready?” asks McCutcheon. McCutcheon hefts the book now presented to him. “I knew it would be a big one,” McCutcheon says of The Stand, a book which today rests comfortably near the top of the bestseller lists. “I’ve cleared my calendar to tackle it tonight.”

McCutcheon has just concluded teaching ‘Salem’s Lot to his Science Fiction and the Occult literature class. That class will be joined this period by another class in creative writing to hear Stephen King speak about the success of horror: Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, Night Shift,and now The Stand.

For a moment, as Stephen King pauses outside the door, he realizes that the circle has come around. For the next 50 minutes the world’s best-selling writer of the macabre will stand in a classroom at Hampden Academy and talk about vampires, as he had eight years before. Eight years filled with so many changes, they might well have been 800 . . . .

***

“I was teaching Dracula here at Hampden Academy. I read it twice and taught it twice to two different classes over a three-week period. I was also teaching Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in freshman English. I was moved by what he had to say about the town. The town is something that doesn’t change. People come and go but the town remains. I could really identify with the nature of a very small town. I grew up in Durham, Maine, a really small town. I went to a one-room schoolhouse. I graduated at the top of my grammar class, but there were only three of us. We had an eight-party line. You could always count on the heavy breathing of the fat old lady up the street when you talked to your girlfriend on the phone. There was a lot to love in the little town. But there was a lot of nastiness too. So I was thinking about Dracula a lot, and I was thinking about Our Town. We were eating supper one night in our crummy little trailer and I was spouting off about Dracula. Tabby said suddenly, ‘What would happen if Dracula came back today? Not to London, but to Herman?’ where we were living. I sort of shrugged it off, but good ideas stick to you like burrs — they won’t let go. I began kicking it over in my mind.

“It always seemed when I taught Dracula that Stoker wanted to make science and rationalism triumphant over superstition. But Stoker wrote his book at the turn of the century. I started mine when we’d seen all the flies on modern science. It doesn’t look so great anymore when you have spray cans dissipating the ozone layer and modern biology bringing us such neat things as nerve gas and the neutron bomb. So I said, I’ll change things around. In my book superstition will triumph. In this day and age, compared to what is really there, superstition seems almost comforting.

“There will always be a special cold place in my heart for ‘Salem’s Lot. It seemed to capture some of the special things about living in a small town that I’d known all my life. It’s funny, but after reading the book people will say to me, ‘You must really hate Maine.’ And I really like it here. The book shows a lot of scars about the town. Yet so much of it is a love song to growing up in a small town. And so many things are dying in front of us—the small stores where the men hang out, the soda fountains, the party lines. Maybe it’s just that when I wrote the book we were so poor and the trailer was little and cold and I could go down to my little furnace room where I wrote with a fourth-grade desk propped on my knees. And when I got excited it jiggled up and down as I hunched forward. Maybe that’s why I like it so much. I could go down there and fight vampires whenever I wanted.”

***

King’s New York agent has said that one of his great appeals is that he places very ordinary people in very scary situations. “People whom you see at McDonald’s. People who listen to rock music on the radio and follow the ball teams and go out for beers.” The kids in this class look at the big guy slouched forward at the podium, his hands used as punctuation marks, and sense he’s really not much different from them.

Their intuition is correct. The big guy, whose book contracts hover near $1,000,000 now, has been a Little League coach; has worked 12-hour shifts in the wet wash of a commercial laundry; has worked in knitting mills from 3 to 11, after attending high school until 2; has pumped gas at an Interstate 95 station; and has picked potatoes for 25¢ a barrel. “I guess the only thing I’ve missed is blueberry picking,” he says.

They open up with questions right away, unlike the uncomfortable diffidence of so many such guest lectures. How about writing? he’s asked. How does he do it? He tells them he writes three single-spaced typewritten pages a day. Every day, with only his birthday and Christmas off. To write these pages he’s at his desk by 8:30 a.m. and stays there until 11.

There will be several more hours after lunch, and, if necessary, after dinner as well. He says that at this rate he can almost always complete a first draft in three or four months, a second draft in another three, and have the whole book out of the toaster within a year. To back him up, there are his five published books, and three more novels completed and on the desk of his publisher.

It sounds so easy. But there’s not time to tell them about the four long-unpublished novels that will take up space in a dusty trunk forever. Lessons in humility that remind him where he came from in the days when he submitted incessantly to Startling Mystery Stories, awaiting their $35 acceptance check, more often than not receiving regrets. When the pulp magazine, the kind that people read on long bus rides, finally accepted one, the editor wrote: “This young man has written many stories for us and we are pleased to be able to publish one at last.” “There were so many times I thought I was pursuing a pipe dream,” King says.

Nor is there time to tell about his concoction of“fried peanut butter and corn chips to keep body and soul together,” while he trained his sights on literary markets named Swank, Cavalier, Gallery,where fiction fleshed out the magazine, so to speak. Something else he doesn’t tell them, but which is obvious to these kids, especially to the ones who even now write their own stories late at night when the house is still, is that this sort of thing has got to be in the blood. It can ‘t be taught and it can’ t be bought.

When people ask, as they usually do, why he writes such horrifying details, he answers, “Why do you assume I have a choice?” He wrote, “My obsession is with the macabre. I have a marketable obsession. There are madmen and women in padded cells the world over who are not so lucky.”

His wife Tabby says, “Steve wrote before anybody was interested, and he’ll write after they’ve stopped being interested in him. I’ve never known him when he didn’t write. And when he’s not writing he ‘s reading. Even when he worked all those hours in the laundry, he’d drag himself to his desk and write. He’s constantly convinced he’ll never finish another book,” she says. “Or when he finishes that he’ll never write another one. I think,” she says, “that if the day comes when he can’t write anymore he would just kill himself.”

***

“My mother brought me and my brother up because our father deserted the family when I was very little. I was always interested in monsters. I read Fate Magazine omnivorously. There are good psychological reasons for my attraction to horror stories as a kid. Without a father I needed my own power trips. My alter ego as a child was Cannonball Cannon, a daredevil. Sometimes I went out West if I was unhappy, but most of the time I stayed home and did good deeds.

“My nightmares as a kid were always inadequacy dreams. Dreams of standing up to salute the flag and having my pants fall down. Trying to get to a class and not being prepared. When I played baseball I was always the kid who got picked last. ‘Ha, ha, you got King,’ the others would say.

“Home was always rented. Our outhouse was painted blue and that’s where we contemplated the sins of life. Our well was always going dry. I’d have to lug water from a spring in another field, and even now I’m nervous about our wells.

“My mother worked the midnight shift at a bakery. I’d come home from school and have to tiptoe around so as not to wake her. Our desserts would be broken cookies from the bakery. She was a woman who once went to music school in New York and was a very good pianist. She played the organ on a radio show in New York that was on the NBC network. My feeling is she took herself and her talent to New York to see what she could find.

“She was a very hardheaded person when it came to success. She knew what it was like to be on her own without an education, and she was determined that David and I would go to college. ‘You’re not going to punch a time clock all your life,’ she told us. She always told us that dreams and ambitions can cause bitterness if they’re not realized, and she encouraged me to submit my writings.

“We both got scholarships to the University of Maine. When we were there, she’d send us $5 nearly every week for spending money. After she died, I found she had frequently gone without meals to send that money we’d so casually accepted. It was very unsettling.

“I had some running battles with those teachers in college who sneered at the popular fiction I carried around all the time. They’d go around all day with essentially unreadable books like Waiting for Godot. I was their court jester. ‘Oh King, he’s got some peculiar notions about writing,’ they’d say.

“When I started Carrie I had finished my first year of teaching. I was working in summer at the laundry to try to make ends meet.

“I started writing but after four pages thought it stank and threw it in the rubbish. I came home later and found Tabby had taken them out and had left a note, ‘Please keep going— it’s good.’Since she’s really stingy with her praise, I did.

“When I finished it I sent it off to Bill Thompson at Doubleday, whom I’d talked to on the phone when I was in college. We were having a really tough time. We had our daughter Naomi, and our son Joe. (There is a third child now, Owen.) Our phone was taken out because we couldn’t afford it. Our car was a real clunker. When the telegram came saying it was accepted with a $2500 advance Tabby had to call me at school from across the street. I was in the middle of a teachers’ meeting and was on pins and needles waiting to get home and hug her.

“Later my agent told me the paperback rights were bought for $400,000. I said, ‘You mean $40,000?’ He said, ‘No, I mean $400,000.’ I realized that meant $200,000 for me and I wouldn’t have to teach anymore.

“My mother was dying then. But she knew everything was going to be all right. She was old-fashioned about Carrie. She didn’t like the sex parts. But she recognized that a lot of Carrie had to do with bullying. If there’s a moral in the book it is: ‘Don’t mess around with people. You never know whom you may be tangling with.’ Ah, if my mother had lived, she’d have been the Queen of Durham by now.”

***

The kids don’t squirm. The low coughing usually present in an English class is absent—because somebody has asked Stephen King about nightmares, about the unspeakable things that everyone carries around from infancy, like secret moles: the voices no one else hears, the night shadows that take form, the impulses to run past the graveyard, even though they have walked past it hundreds of times before, but always in the light. They know this man knows of such things. How else could he have created a Carrie who, in the ultimate dump-on, destroys her high school with her powers of telekinesis? Or the terrifying claustrophobia in The Shining when a family of three is snowbound in a malevolent hotel, as a small boy’s psychic powers unleash the dry charges of evil? Or the trucks that run down their owners in his collection of short fiction called Night Shift? Or the toy soldiers in the same collection that begin firing real bullets? Or the man who gets something bad in his beer and begins to turn into a puddle of goo? Or, finally, The Stand, his tale of the survivors of a flu epidemic who converge on both sides of the Rockies, drawn in turn to forces of evil and of good, knowing only one side may endure? And they want to ask him: “How can you write about a man of goo, then sit down upstairs with your children and eat pizza?”

***

“After ‘Salem’s Lot we went to Colorado because I wanted a book with a different setting. And nothing was coming. Somebody said we should go to Estes Park, which was about 30 miles away, and stay at the Stanley Hotel, a famous old hotel that supposedly was where Johnny Ringo, the legendary badman, was shot down.

“We went up there the day before Halloween. It was the last day of the season and everybody had checked out. They said we could stay if we paid cash because their charge-card blanks had been shipped off. Well, we did have cash and we did stay. We were the only guests in the hotel and we could hear the wind screaming outside.

“When we went down to supper we went through these big bar-wing doors into a huge dining room. There were big plastic sheers over all the tables and the chairs were up on the tables. But there was a band, and they were playing. Everybody was duded up in tuxedoes, but the place was empty.

“I stayed at the bar afterwards and had a few beers and Tabby went upstairs to read. When I went up later, I got lost. It was just a warren of corridors and doorways, with everything shut tight and dark and the wind howling outside. The carpet was ominous with jungly things woven into a black and gold background. There were these old-fashioned fire extinguishers along the walls that were thick and serpentine. I thought, ‘There’s got to be a story in here somewhere.’

“That night I almost drowned in the bathtub. They were great deep tubs that ought to have had hash marks on the side. I thought if I could get just a few people in there and shut them up . . . .

“I write my nightmares out. Occasionally somebody will say to me, ‘I got a nightmare from reading your book,’’ and my immediate reaction is, ‘Serves you right for reading it.’ Because when you get to the bottom of everything, what I’m involved in is trying to scare the bejeesus out of people. You aren’t there for tea and cookies, but to serve people’s darker tastes.

“When I was writing The Shining there was a scene I was terrified of having to face writing. Writing is a pretty intense act of visualization. I won’t say it’s magic, but it’s pretty close to magic. There was this woman in the tub, dead and bloated for years, and she gets up and starts to come for the boy who can’t get the door open.

“The closer I got to having to write it, the more I worried about it. I didn’t want to have to face that unspeakable thing in the tub, any more than the boy did. Two or three nights running, before I got to that section, I dreamed there was a nuclear explosion on the lake where we lived. The mushroom cloud turned into a huge red bird that was coming for me, but when I finished writing the scene, it was gone.

“My favorite scene in The Stand is when Larry Underwood, a rock singer, and his girlfriend are trying to escape New York City. You have to remember nearly everybody in the country is dead. He gets into an argument with her by the Lincoln Tunnel. The tunnel is jammed both ways with cars whose drivers died before they could get out. The only way out is to walk the two miles through the tunnel, around all the cars, and all the bodies inside. And there are no lights.

“He starts through the tunnel, alone, and gets about halfway. And he is thinking about all the dead people in their cars and he starts to hear footsteps and car doors opening and closing. I think that’s really a wonderful scene. I mean can you imagine that poor guy?”

***

The bell rings, breaking King off in mid-sentence. When the class is over he is going to the home of his former teaching colleague to listen to music and drink beer, maybe break into a poker game. He works almost as hard at keeping his perspective as he does on his writing. He has seen what eight years like these have done to other writers, seen them mutate into celebrities.

He is teaching this year at his alma mater, for “revenge on my old teachers,” he laughs, but more seriously admits he needed to rejoin the real world for a while.

But he must juggle demands on his time so that he feels already “a little pawed, like an item at a bazaar.” He doesn’t get to his lakefront home in Lovell often enough, and frets that perhaps he must move, and move again, until he finds the balance of peace and activity that he needs. With something akin to slowly dawning horror he is beginning to realize that perhaps, for one of the three or four best-selling novelists in the world, there is no such place.

When he lived on another lake, in Bridgton, the police remembered that he would buy his bologna by the case, just as they did themselves. That he went to bean suppers and the meetings at the elementary school. But if somebody asks his neighbors where Stephen King lives, there is the sudden silence of country people on their guard.

Because in their wisdom they know something King suspects, that despite bologna and torn denim jackets, he can never be just “the tall man” again.

***

“I’m very leery of thinking that I’m somebody. Because nobody really is. Everybody is able to do something well, but in this country there’s a premium put on stardom. An actor gets it, and a writer gets it. I read Publisher’s Weekly and more and more I see people compared to me. In the review of a horror novel they’ll write, ‘In the tradition of Stephen King ….’And I can’t believe that’s me they’re talking about. It’s very dangerous to look at that too closely, because it may change me from what I want to be, which is just another pilgrim trying to get along. That’s all any of us are.

“You know, my editor calls New York ‘GWOP’—the ‘glamour world of publishing.’ Everybody is really a little kid inside, and it’s like playtime in New York. It’s where we take off our Clark Kent outfit and turn into superwriter.

“We had lunch at the Waldorf with people who bought the movie rights to The Shining. (The Stanley Kubrick film starring Jack Nicholson is due for release Christmas, 1979.) We sat in leather chairs. Mine was dedicated to George M. Cohan because it was where he used to sit and compose. The waiters are all French. They glide over to you.

“And we sat around the table talking seriously about people to play roles in the movie. ‘What do you think about Robert DeNiro for the father?’ someone says. Somebody else says, ‘I think Jack Nicholson would be terrific.’ ‘And I say, ‘Don’t you think Nicholson is too old for the part?’ And so it goes. We’re tossing around these names from the fan magazines—except it’s for real. Then the check comes and it’s $140 without drinks, and somebody picks it up without batting an eye.

“Then I come back to Maine and pick up the toys and check if the kids are brushing in the back of their mouths, and I’m smoking too many cigarettes and chewing aspirins alone in this office, and the glamour people aren’t here. There is a curious loneliness. You have to produce day after day and you have to deal with doubts—that what you’re producing is trivial and, besides, not even good. So in a way, when I go there, to New York City, I feel like I’ve earned it. I’m getting my due.”

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen