Divide and Conquer

Fred Lynch is one of my favorite painters. He is a painter’s painter, rigorously disciplined about his work and primarily intent upon pleasing himself. In the catalogue of his 2005 Form & Counterform 20-year retrospective at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine, Lynch wrote as succinct an artist’s statement as I have ever read: […]

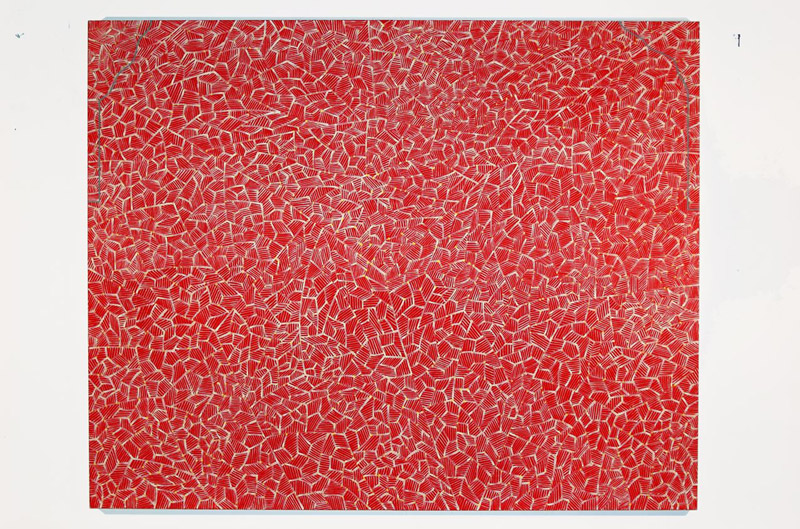

Painting by Frederick Lynch

Fred Lynch is one of my favorite painters. He is a painter’s painter, rigorously disciplined about his work and primarily intent upon pleasing himself.

In the catalogue of his 2005 Form & Counterform 20-year retrospective at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine, Lynch wrote as succinct an artist’s statement as I have ever read: “I like to paint. I like my studio. I spend most of my time there, combining things that I remember and imagine with things that I see and feel, translating all this into images that I want to look at. My intention is beauty – my goals, pleasure and joy.”

Shortly, Fred Lynch will have two solo exhibitions up in New England – Division and Discovery: Recent Work by Frederick Lynch at the Portland Museum of Art (February 27 to May 16) and Frederick Lynch: Visual Inquiries at Connecticut College’s Cummings Arts Center in New London (January 26 to February 26). Both exhibitions draw on recent bodies of work that extend Lynch’s sustained abstract inquiry into the nature of form.

For two decades now, Lynch has been primarily a formalist, working with pure geometry and patterns in ways that recall Josef Albers’ theoretical explorations of the square. But imagery that has long since become structural and formal began as decorative elements in his figurative abstractions of the 1970s and 1980s.

In a 1975 watercolor of a female torso hanging in my living room, folds of shirt striping form the background. In a 1982 print here in my office, another female form stands behind a tabletop still-life, all the elements of which are covered in patterns of stripes and checks. By 1990, when the red and white striped painting in my living room was painted (a deep, rich painting that looks rather like a fragment of the American flag), Lynch had abandoned representation altogether in favor of a vocabulary of pure form, shape, pattern, and color.

The works in his Portland Museum of Art and Connecticut College shows are from his Divisions and Segments series. I tend to think of them as exercises in visual logic. And while I have not always been able to appreciate the logic he finds so beautiful, I respect the tenacity and integrity of Fred Lynch’s work. Using repetitive branching patterns that have their genesis in nature, he undertakes an almost mathematical construction, sometimes metastasizing as over-all pattern abstractions, sometimes, as in the Segments series, concentrating on discrete elements, analyzing form even as he creates it.

“Divisions,” explains Lynch on his website, “is based on an idea that repeated sectoring of a given area can produce infinite shape variations. The resulting visual effect is a systematic display of controlled chaos and random patterns. Each shape, possibly unique among 1500-2000 adjacent shapes and framed by upwards to 15,000 lines, is initially formed by a more or less 120

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem