Dahlov Where the Wild Things Are

Dahlov Ipcar, 92, is a Maine state treasure. The daughter of painter Marguerite and sculptor William Zorach, Ipcar is perhaps the best-known and best-loved artist in the state, celebrated for her lifetime of creativity and her sustained vision of the transformative power of the imagination. “I have come to feel that the reality created by […]

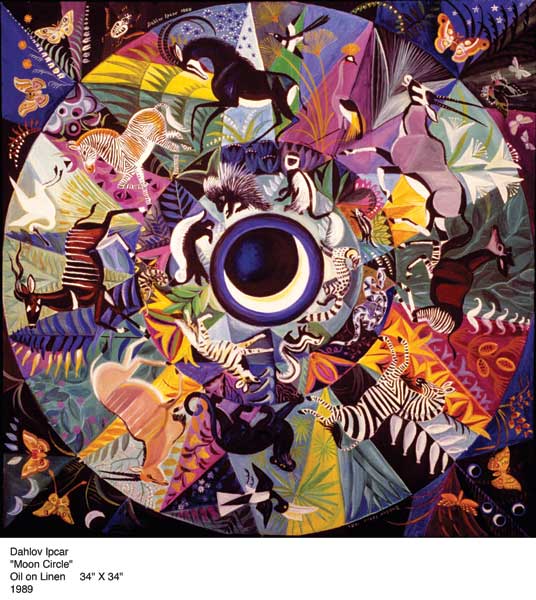

“Moon Circle”, by Dahlov Ipca

copyright 2010, Dahlov Ipcar, from The Art of Dahlov Ipcar, Down East Books, www.downeastbooks.com

Dahlov Ipcar, 92, is a Maine state treasure. The daughter of painter Marguerite and sculptor William Zorach, Ipcar is perhaps the best-known and best-loved artist in the state, celebrated for her lifetime of creativity and her sustained vision of the transformative power of the imagination.

“I have come to feel that the reality created by the artist is more important than actual reality,” Ipcar wrote in 1990 on the occasion of a major exhibition at the Bates College Museum of Art. “The real world may come to seem oppressively dull and barren unless transformed and revitalized by imagination.”

Dahlov Ipcar is now the subject of a delightful new book, The Art of Dahlov Ipcar (Down East Books, $50 hardcover) by poet and art critic Carl Little. Open the book on a dreary day and you will let light into you life as the chromatic fantasies of Ipcar’s fabulous animal paintings dance before you eyes. Barnyard roosters, calico cats, sleek hounds and sturdy farm horses run through the pages in pursuit of zebra, gazelle, lions, tigers, leopards, elephant and hippos.

Though she has painted the beasts of the barn, the field, the forest, the savannah and the jungle all her long life, Ipcar’s beautiful, benevolent bestiary evolved over time from the naturalism of her early years to the stylized, Cubist-influenced tableau of her mature style and on to the kaleidoscopic visions she has painted in recent years. At times it almost seems that animal life is just the armature to which Ipcar applies pattern and color.

Ipcar’s felicitous, fanciful style lends itself readily to illustration and, as author/illustrator of some 31 books, among them Animal Hide and Seek (1947), One Horse Farm (1950), Brown Cow Farm (1959), Lobsterman (1962), and The Calico Jungle (1965), she ranks right up there with Barbara Cooney and Robert McCloskey among Maine’s great children’s book artists.

The seat of Ipcar’s imagination is the family farm in the Robinhood section of Georgetown, but, having been born into a bohemian family of modernist artists, her imagination continues to run free, undiminished since childhood. Dahlov Ipcar is no Pollyanna, however. She employs art as a defense against despair, disillusionment, loss, and the ravages of old age. What amazes those who know her is simple fact that Dahlov just keeps going and going. She’s been painting about 10 paintings a year all her life. Last year, she painted 18.

“My hand’s steadier now than it was when I was younger,” Dahlov told me earlier this year when I talked to her about the making of a video documentary about her career.

So, too, is her faith in the power of art to make life meaningful. Carl Little concludes The Art of Dahlov Ipcar by quoting the artist as saying, “I hope I die before I run out of vermilion.”

Now that’s life as art for you.

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem