Painterly Sleight of Hand in New Britain

John Haberle once painted a $10 bill with such verisimilitude that a critic of his day insisted it was real currency affixed to the canvas. That painting, “U.S.A (The Chicago Bill Picture), ca. 1889,” is one of some 20 paintings and drawings currently assembled as John Haberle: American Master of Illusion at the New Britain […]

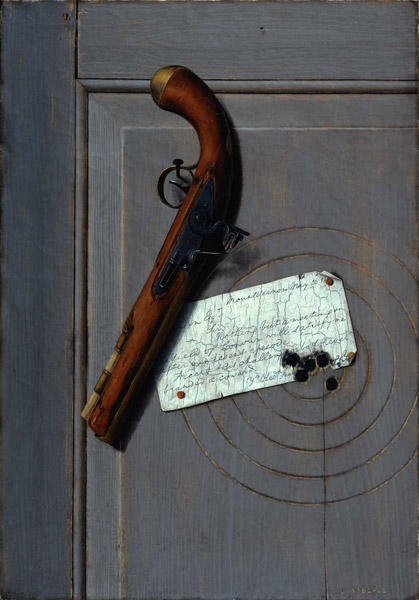

The Challenge, by John Haberle

John Haberle once painted a $10 bill with such verisimilitude that a critic of his day insisted it was real currency affixed to the canvas. That painting, “U.S.A (The Chicago Bill Picture), ca. 1889,” is one of some 20 paintings and drawings currently assembled as John Haberle: American Master of Illusion at the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut (through March 14).

Haberle (1856-1933) was, along with his better known contemporaries William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) and John Frederick Peto (1854-1907), a true master of the art of trompe l’oeil painting. The preternatural ability to create such vivid illusions with paint and brush as to fool the eye (trompe l’oeil) is by and large a lost art, but the work of these turn of the last century illusionists still holds a fascination for those who value imitative skill and, in Haberle’s case, paintings that are meant to be solved as well as seen.

John Haberle, who spent most of his life in New Haven, worked as an engraver and as an exhibition preparatory at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale. Between 1887 and 1909, he created some 40 incredibly detailed and enigmatic trompe l’oeil paintings before his failing eyesight (a result of years of painstaking, eye-straining work) put a premature end to his artistic career.

John Haberle: American Master of Illusion showcase and provides context for “Time and Eternity, ca. 1889-90” and “Night, ca. 1909,” both of which are in the collection of the New Britain Museum of American Art.

“Time and Eternity” is a vanitas painting that features objects – a pocket watch, playing cards, a rosary, a photograph of a girl from a cigarette package, a pawn receipt, a theater ticket, and a newspaper clipping – meant to conjure the transience of life. In keeping with the visual games Haberle liked to play, the objects appear to be hung on the backside of a painting that is tacked into the frame and facing away from the viewer.

“Night” is large by Haberle standards at 6 1/2 feet by 4 feet and creates the illusion of stained glass windows framing an unfinished painting of a nude. Such was Haberle’s sleight of hand and penchant for deception, however, that art historians differ on whether it is indeed unfinished. As the New Britain Museum didactic label points out, “Alfred Frankenstein, one of the most renowned Haberle scholars, believed that the artist had intended to trick viewers into thinking the painting was unfinished. Night, he says, ‘is a completely finished picture of an unfinished picture.'”

So if you get to New Britain, don’t be fooled. There’s probably more going on in any of the Haberle pictures than the eye can comprehend. John Haberle: American Master of Illusion is accompanied by a handsome catalogue (distributed by University Press of New England, $25 softcover)with new scholarship by art historian Gertrude Grace Sill and will travel to the Brandywine River Museum, in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, from April 17, 2010 through July 11, 2010 and to the Portland Museum of Art in Portland, Maine, from Sept. 18, 2010 through Dec. 12, 2010.

[New Britain Museum of American Art, 56 Lexington St., New Britain CT, 860-229-0257.]

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem