A Fatal Mistake | The Sinking of the El Faro

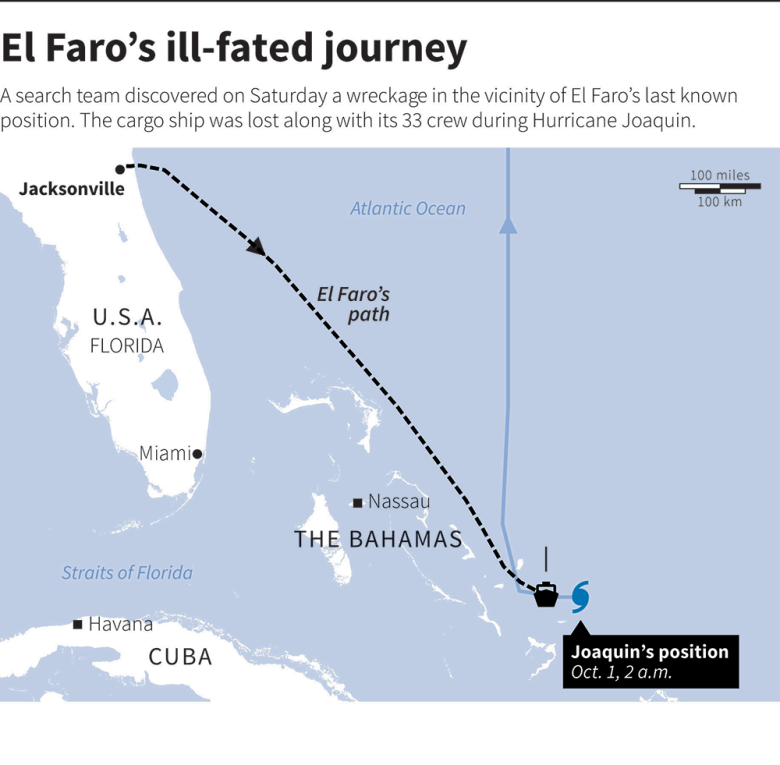

On October 1, 2015, the container ship El Faro sailed directly into the path of Hurricane Joaquin. When it sank it took the lives of all 33 aboard, including eight New Englanders. Rachel Slade wanted to know what happened and why. You will not soon forget what she found.

Videos taken 15,000 feet below the ocean surface showed the ghostly sight of El Faro’s stern, which became the epitaph of a

maritime tragedy whose final hours will likely forever be shrouded in mystery.

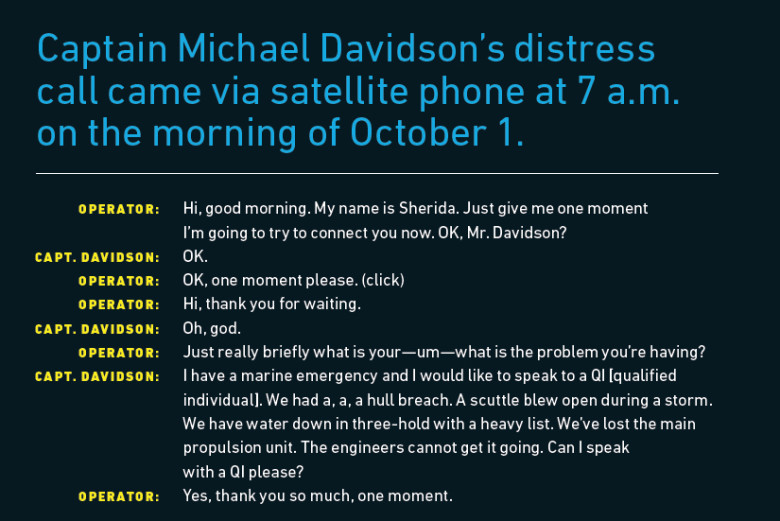

The operator put Davidson on hold and then the line went dead. Captain John Lawrence, the shipping company’s designated person on call, had received a similar voicemail from Davidson just minutes before and was trying in vain to reconnect with his colleague at sea. Seventeen minutes later, three automated distress signals from the El Faro triggered a massive Coast Guard search. After flying and sailing for eight days over 183,000 square miles around the ship’s last known position, the effort turned up an oil slick, a debris field, and a person so battered as to be unrecognizable floating in a survival suit.

When news broke of the vessel’s disappearance, people wanted to know how a modern American ship as big as Boston’s Hancock Building could sink without a single survivor. Why did the captain steer directly into the path of a hurricane? Why did the engines fail? Who’s responsible? Marine experts pointed to El Faro’s advanced age, or the company’s alleged greed, or the captain’s supposed arrogance in single-mindedly pursuing what became his deadly route.

In November 2015, a remote-controlled deep sea explorer launched from Woods Hole, Massachusetts, plunged 15,000 feet below the Caribbean Sea to photograph El Faro’s bruised, twisted hull. The ship’s bridge had been violently torn from the boat, and lay half a mile away on the ocean floor.

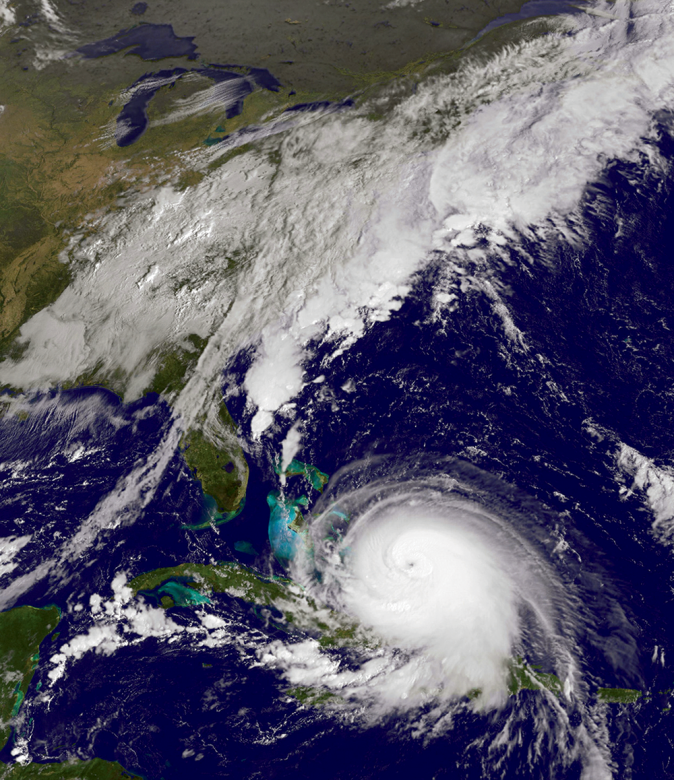

Photo Credit : NOAA via Associated Press (Satellite Photo)

A federal investigation—four weeks of hearings held three months apart in Jacksonville, Florida—was jointly conducted by the U.S. Coast Guard and the National Transportation Safety Board. The proceedings produced copious testimony from former crew members, weather experts, shipping professionals, and shipping company executives. But no clear answers. In August 2016, another deep sea explorer retrieved the ship’s voice data recorder, which provided audio from the bridge, recorded in the hours leading up to the sinking. On it, you can hear the captain order the crew to abandon ship. It will likely take months before an official report is issued, and even then, we may never know exactly what happened on board El Faro that day.

In the spring of 2016, I became obsessed with shipping and the mystery of the El Faro. As I dove deeper into the tragedy, I began to ask a different question: What forces had brought that ship, and those sailors, including eight New Englanders—Michael Davidson, Danielle Randolph, Michael Holland, and Dylan Meklin from Maine; Jeffrey Mathias, Mariette Wright, and Keith Griffin from Massachusetts; Mitchell Kuflik from Connecticut—to that particular place at the particular moment, when a normally calm sea surged dozens of stories high, rolled the enormous vessel, unseated its cargo, and sent it to the deep?

Few Americans spend much time thinking about the industry, but cheap global shipping is the backbone of 21st-century life—it’s how we get $300 Chinese-made laptops and $12 Indian-made cotton T-shirts. About 90 percent of worldwide trade travels by sea. Sift through stacks of H&M jeans or walk the shoe aisles at T.J. Maxx and inhale the shipping container’s stale perfume; that’s the scent of commerce.

From an airplane, cargo ships look like steel alligators creeping up brown rivers, or barely visible specks cutting a perfect wake in the open sea. Dockside, they’re awesome and remote—with steel prows rising 30 feet up above the waterline, blue and red containers stacked eight stories high, and enormous propellers below.

The huge boats have their fans, too: With vessel-tracking websites like marinetraffic.com, you can follow ships as they travel around the globe. Each fuel-guzzling leviathan transporting millions of dollars of cargo, crewed by a handful of sailors watching the horizon for pirates or weather, appears on the screen as a small, colored blip. Hobbyist ship-spotters regularly upload time-stamped photos of the boats they’ve seen.

Throughout the spring, I streamed the hearings while driving or doing the dishes. I eavesdropped on chat rooms where professional seamen debated every revelation or news report. I researched the history of international shipping and the U.S. Merchant Marine, and visited the Maine Maritime Academy in Castine where young men and women were preparing to sail to Europe aboard the school’s training ship, the State of Maine. Their excitement was so contagious that I felt the pull to steam across the Atlantic with them. I wanted to experience the vastness of the ocean among confident young sailors and knowledgeable mariners. What was it like to be cut off from the world, focused only on the rigors of seafaring?

Instead, I sat for seven hours a day in the overly air-conditioned Jacksonville convention center-turned-courtroom listening to testimony. Relatives of those lost occupied the front rows facing the investigative panel, while TV crews and journalists watched from the back. Under oath, experts and mariners answered the panel’s questions with their backs to us; unable to see their faces, I could hear the concern or fear in their voices.

During breaks, many of us escaped the room’s chill to thaw in the Florida sun. That’s where I met Jill Jackson-d’Entremont, who’d recently moved from Philadelphia to Florida to be closer to her brother, Jack Jackson, an able seaman. When he was lost on the El Faro, Jill went to clean out his house and found his laundry still in the dryer.

Each lost sailor had stories he or she could not tell. To learn them, I needed to get closer to those they left behind. One chilly Sunday morning, I headed north to meet Deb Roberts.

Photo Credit : Photograph by Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images | El Faro crew courtesy of their families.

Wilton, Maine, is landlocked and rural. To get there, take Route 4 out of Lewiston and follow the trail of used car dealerships, gun stores, and gas stations, over the Androscoggin River (just around the bend from the ailing Verso Paper Mill) to the foot of Wilson Lake, where a hard right gets you to the town of 2,000. Main Street’s offerings: a public library, bank, and post office. This is where Michael Holland lived—raised in nearby Jay, where he played high school football and got his first shotgun at age 16. This is lake and mountain country; the ocean seems worlds away.

Deb Roberts sent two sons to the Maine Maritime Academy. Michael was her oldest. After graduating in the spring of 2012, he went to work in the hot, humid, earplug-and-earmuffs-loud El Faro engine room to finance his life on land.

Southerners send their children to the military. New Englanders send their children to sea. Even before the American Revolution, a 12-year-old Maine boy could work in a ship’s galley and emerge a decade later as captain of his own vessel. After the revolution, the country depended on New England’s maritime prowess to feed its people and drive its economy. By the late 1700s, 90 percent of federal revenues came from the region’s merchants, so much so that when drafting the country’s first laws, Alexander Hamilton continually consulted with his Essex Junto—merchants who had opened up trade in places as far-flung as Guangzhou, the Pacific Northwest, and Fiji, and were now running large fleets from Salem, Newburyport, and Boston.

Like countless Maine boys before him, Michael had a plan: He’d bought a house in Wilton where he hoped to start a family, and once he owned the house outright, he would give up his life at sea for a job running a local power plant, just as his football coach had done. To Michael, friends came first, and he had plenty of them. “Michael would just be the first to volunteer, to try something crazy, to live life to the fullest,” Deb says, sitting across from me at her dining room table. “He had no idea that he just had 25 years to do it, but he lived as though he did.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Behind her, a corner cupboard had been given over to “El Faro 33” gifts and mementos, which spilled onto the adjacent sideboard. On a shelf, a photo of Michael next to his first deer kill shows him long and lean—a boy who had suddenly found himself in a man’s body. In his Maine Maritime Academy graduation picture, you can see the wispy hint of a nascent mustache; his white officer’s uniform is snug in the middle where four years in a classroom softened the former athlete.

While Michael was at sea, Deb kept busy. She lobbied Maine legislators for a tax exemption for young mariners, worked as an administrator in the Jay school system, raised her other two children, and went at the weeds in her garden with a vengeance.

Michael preferred doing rather than pondering, just like his mother. “I never really got into a lot of conversations with Mike about the nitty-gritty details of shipping,” Deb says. “When he was home, it was about, What you making for dinner, mom? You got any leftovers? Did you go hunting? Did you go fishing? Did you catch any fish? Did you go to camp? You know, those types of things. We never talked shop, just the big things.”

But Deb noticed a change in Michael over his final summer. “We saw him more than we had seen him at all before,” she said. “You know, he lived 10 minutes away and we’d hardly ever see him. He was a single guy and when he was off on his Saturdays, he was off having fun.” Now that Michael had starting dating a nurse from Jay named Kelsea who worked in Farmington, Deb says, “I saw him settling down. I really did—I saw him becoming a grown-up.”

On Tuesday morning, September 15, Michael flew down to Jacksonville to join the crew of the El Faro for its final Puerto Rican run. Kelsea drove him to the Portland airport. The evening before he left, Deb brought him his favorite Greek pizza and reminded him to work on his Christmas list and text it to her so that she could start shopping for him. “Then I gave him a hug and a kiss, told him I loved him, and to have a great trip and I’d see him in November.”

Hurricane Joaquin began as a tropical depression in the Atlantic Ocean on September 28, the day before the El Faro left Jacksonville. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) predicted that as it intensified, the storm would get pulled north toward Atlantic City by a low-pressure system. This forecast proved dead wrong.

Even with all our technology, predicting the weather is still very much an art form. It begins with plugging raw data—temperature, barometric pressure, and regional systems—into dozens of computer models, which then generate various storm trajectories and strengths. The models rarely show identical storm paths and intensities, but often, a pattern emerges. Specialists analyze these patterns using their knowledge of past storms to guide them. By the time an NHC forecast is published, the data on which it’s based is at least six hours old.

More information increases accuracy. On land, data is in abundance. Every city, town, and airport across the country constantly records and reports minute changes. At sea, information is spottier; raw data comes from aircraft, ship-to-shore reporting, and weather balloons.

Storm intensity and trajectory are notoriously difficult to predict in the tropics. Due to winds, ocean temperatures, and changing currents, systems bounce around in confounding ways. Tom Downs—a professional meteorologist for Weather Bell, a private service that independently analyzes raw data and comments on the official forecasts—compares predicting tropical storms to trying to follow the end of an uncontrollable fire hose.

Photo Credit : Rueters/NOAA

But on Tuesday, September 29, at 6 a.m., 15 hours before the El Faro left Jacksonville, Downs and his fellow Weather Bell analysts saw enough in their models to challenge the NHC forecast. They sent their clients a warning that the nation’s weather prediction was wrong: “While acknowledging this is tricky and not as obvious to me as Sandy,” the report said, “I am not just winging it … to be blunt it really has an ugly idea and is farther to the west than NHC. Given what is setting up in front of this (with the rain and easterly flow), this would be a disaster.”

That evening, Captain Eric Bryson, a ship’s pilot for Jacksonville Port, was waiting at home when the call came: The container ship El Faro was ready to leave port for its usual run south to Puerto Rico. At 7:30 p.m., he walked up the gangway of the ship to the top deck, then up several flights more to the bridge, where he met with the ship’s master, Michael Davidson. After a cup of coffee, Bryson stepped out into the night air on the port-side balcony. It was a balmy 80 degrees and calm under mostly cloudy skies. Looking up St. Johns River, Bryson prepared to guide the huge ship from the busy port east to the sea.

As a pilot, he was familiar with many of the El Faro’s crew, and had a special fondness for second mate Danielle Randolph, whom he’d known since she was a cadet working on the sister ship, El Morro, 12 years before. “On the bridge, she was always happy and friendly, and certainly all business,” he told me over the phone. That evening, he had heard Danielle on the walkie-talkie reviewing the cargo—294 cars, trucks, and trailers below deck, as well as 391 containers on its top deck. Remembering her, Bryson said, “She was uncommonly nice.”

—

Danielle spent her childhood in Rockland on the Penobscot Bay, determined to work on the ocean. Her passion started early: “I remember taking Danielle to kindergarten,” her mother Laurie Bobillot tells me, “and, you know, being my oldest, when I took her to school I was bawling my eyes out. I said to her, ‘Oh, I don’t want you to go to school.’And Danielle goes, ‘Mama! I want go! I want to learn about the water!’ And I’m thinking, ‘Wow, this is just kind of weird.’”

In the summers, Danielle worked on the docks of Port Clyde for her aunt’s lobster business, and at the O’Hara Corporation—a fishing consortium and marina in Rockland. In the fall of her senior year at Rockland High School, Danielle only applied to the Maine Maritime Academy. That’s not how it works, her mother counseled her. You apply to a lot of schools and hold your breath. Danielle replied, “Mother, I’m going to MMA and that’s that.”

During her freshman year at the academy, Danielle phoned home to ask Laurie, a hairdresser, about hair loss. Was it normal to clog up the shower drain? Sure, she answered. Everyone sheds. When Laurie saw her daughter that spring, she was alarmed to discover that the stress of college had created bald patches in Danielle’s thick blonde locks. Her daughter shrugged it off. That was her way: She soldiered through.

Later, as a deck officer aboard container ships for TOTE Maritime, Danielle earned a reputation for holding her own as a cheerful, wisecracking, hard-working woman in the largely male industry. Still, she painted her stateroom pink and decorated the drab ships’ interiors for Easter and Christmas. As soon as she returned to Maine from each tour of duty, she’d shop for shoes and vintage ’50s dresses and snuggle with her calico cat, Spot.

For 10 years, she worked several stories above where engineers like Michael Holland labored in the engine room. She calculated loads, watched the weather, carried out orders. She was busy, and liked it that way.

But months-long stints away, hampered by limited cell and Internet service, made it difficult to maintain friendships. Danielle tried dating another sailor, but ended the relationship when she feared that settling down would ruin her career. When Danielle did reach out to her family while she was at sea, her messages were brief, impersonal, signed with a simple, brisk “-D.”

As a deck officer in a quasi-military industry, Danielle was trained to follow commands and avoid questioning her superiors. If she had concerns, her style was to walk away and think over the situation in private rather than confront it directly. Her stoic nature dovetailed well with the merchant marine, where life is about order, checklists, protocols. It’s an industry that attracts people who prefer solving problems with a wrench. Many mariners speak wistfully of the peace they find on board, where they are temporarily cut off from the noise of the world.

Though Danielle and her mother were close, she rarely talked about her life at sea. But lately, Danielle found herself serving under a steady churn of new masters. Some were hands-on—walking the decks and running daily drills to keep the crew up-to-date, alert, and engaged. Others disappeared into their staterooms and let the ship run itself, trusting their mates to be their eyes and ears.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the Randolph Family

Technology may have transformed the industry, but the captain still sets the culture aboard ship, just as he did in the 19th century. When Captain Ahab appears three days into the Pequod’s voyage, Melville writes: “Not a word he spoke; nor did his officers say aught to him; though by all their minutest gestures and expressions, they plainly showed the uneasy, if not painful, consciousness of being under a troubled master-eye.”

In May, TOTE had forced the resignation of Captain Jack Hearn, who’d served the company on and off for 28 years, 25 as master. Same with Captain Peter Villacampa, who had originally hired Danielle. Steven Shultz, the first mate on the El Faro’s final voyage, had been in that position only since August. There was barely time for each new captain to establish a rhythm, and there was even less job security. Nearly everyone was considered temporary.

In shipping, where you learn on the job, turnover can lead to a critical loss of knowledge. Some former El Faro crew members testified that they gleaned more about the aging boat they served by stumbling onto manuals on board. At the hearing, former Captain Hearn testified, “When I first transferred [to TOTE], there was tremendous experience on the specific run. After 10 years in the company moving up through the ranks, they knew their job, and they had a good mentoring program. By the time I was leaving [in 2014], that was changing. There was less experience both on the deck and in the engine room.”

Thousands of containers are lost at sea every year because they weren’t securely fastened. When a storm batters a boat, improperly tied cargo can crash onto the decks or slide around in the hold, compounding a ship’s roll. Hearn described using a tool for testing the “button”—the latch on the deck floor to which lashings were fixed. Later, a TOTE chief mate claimed that he’d never heard of the tool. Marine architects specified that El Faro’s cargo lashings should come from the button at a 45-degree angle, but some crew members said they didn’t know why that angle was important, or even how to test the lashings. Lashing tension—critical to its performance—was tested on board by feel. At sea, knowledge can be the difference between life and death.

Privately, Danielle hinted to her mother that she might be over it. The culture at TOTE had changed. She considered going back to school to study maritime law, or working on an oil rig.

On September 28, as she was preparing to fly down to Jacksonville for yet another tour on the El Faro, Danielle hemmed and hawed. It wasn’t like her. “She just felt that something wasn’t right,” Laurie says. “She didn’t want to go out shipping this past September, which was really weird. That was the first time ever, ever, that we heard the kid say, ‘I really don’t feel like going.’”

By 8:25 on the evening of September 29, the El Faro’s crew dropped the last of its lines and Captain Bryson guided the boat down the river. While he worked, he chatted with the ship’s master, Michael Davidson, and Jack Jackson. The men discussed the usual things, Bryson testified, including water traffic. They also touched on the tropical weather system building in the Atlantic. “I don’t recall what I saw or said,” Bryson told the investigative panel, “but Davidson said, ‘We’re just gonna go out and shoot under it.’ It was audible to everybody. No one reacted.”

An hour later, Bryson had navigated the El Faro to open water off the coast of Florida and prepared to disembark. He climbed down the side of the cargo ship by rope ladder and onto the pilot boat. At 9:30 p.m., the tug turned and headed back to land. Bryson would soon be the last person alive to have stood on the El Faro’s decks.

Through the night and into Wednesday, the tropical storm lumbered stubbornly along its southwestern path, just as Weather Bell predicted, slowing down and gaining intensity. By daybreak on September 30, the NHC declared the system a Category 1 hurricane named Joaquin, with a center located approximately 125 miles north of the Turks and Caicos Islands, but the forecast didn’t alter its predicted path. The El Faro sped down the Florida coast along its usual southeasterly route.

Captain Davidson had graduated from Maine Maritime Academy more than a decade before Danielle and Michael. Slim with salt-and-pepper hair, 53 years old, he had grown up on the Maine coast, where reminders of a glorious maritime past haunt every corner; where majestic inns are named for sea captains, like Camden’s Captain Swift Inn, Searsport’s Captain A.V. Nickels Inn, and the Captain Jefferds Inn in Kennebunkport; where official town welcome signs often depict schooners at full sail. Even the names—Searsport, Bucksport, Kennebunkport—speak to their nautical importance. This is where, for generations, boys went to sea to support their families through shipping, whaling, or fishing. Some never came back.

Davidson had spent his youth on the water. He’d mastered boats for Casco Bay Lines along the Maine coast and tankers in the Gulf of Mexico for ConocoPhillips before joining TOTE Maritime in 2013 to tag-team the Puerto Rican run. He made a good living, enough to maintain a 4,100-square-foot home on a cul-de-sac outside of Portland for his wife, Theresa, and his two athletic daughters. Now that the girls were in college, expenses were high. Fortunately, mastering container ships paid well, if you could get the work.

The day before, TOTE had offered Davidson time off. He declined, saying that he didn’t want to lose vacation days because he wanted to complete his shift in time for his 25th wedding anniversary.

The El Faro was 28 years older than the average cargo ship docking in American ports, ancient by international shipping standards. It had already lived several lives since it had been built in Pennsylvania during the Nixon administration. Originally christened the Puerto Rico, it was one of the last vessels produced by Sun Shipbuilding & Drydock Co. before the yard shut down. For nearly two decades, the ship carried cargo between San Juan and the East Coast of the U.S. for a Puerto Rican outfit. In 1991, Saltchuk, the Seattle-based parent company of TOTE, assumed ownership. The boat was conscripted to transport military cargo for two wars, and after being lengthened 90 feet in 1993, served in the rough Alaskan waters as the Northern Lights before traveling through the Panama Canal one last time to do the San Juan run again as the El Faro.

When news of the El Faro’s disappearance hit, a handful of Sun retirees reminisced on online message boards about building it. After the accident, Deb Roberts received a ship in a bottle handmade by a former Sun shipbuilder named John Glanfield, who said he had worked on the El Faro; he still felt a connection to the boat he’d help construct so many years ago.

The El Faro flew the American flag, and this is significant. One of the earliest acts of the U.S. government was to protect its maritime interests by forbidding foreign ships from participating in the country’s coastal trade. Some 200 years later, vessels hauling cargo between American cities must be domestically registered, built stateside, and crewed by citizens—members of the unions—following American labor laws. This legislation, known as the Jones Act, is designed to ensure that the U.S. isn’t forced to depend on a foreign entity for transporting goods, cargo, or troops during wartime. It also guarantees that America retains a certain level of nautical knowledge, should it ever find itself globally isolated.

And yet, the laws plague American shipping. Because U.S.-built vessels cost at least twice as much as those made in Asia, shipping companies often keep their woefully outdated boats longer than they should. It’s simply too expensive to upgrade their fleets. Many of the El Faro’scomponents, including its open lifeboats—just like those you’d find on the Titanic—were grandfathered in. Its power plant was also ailing. A compliance agent testified during the hearings that she wouldn’t bring its boiler up to full pressure because, well, it was old. In fact, one of two boilers on the El Faro’ssteam plant had been shut down for inspection just before its fateful run, and was found to have significant problems. For this reason and others, the Coast Guard put the boat on a watch list; the El Faro was scheduled to be dry docked and overhauled in November before going back to Alaska.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of TOTE Maritime

At its peak, the American merchant marine moved 40 percent of the world’s trade. Then shippers began registering their boats in foreign countries to get around Jones Act requirements. Now the American merchant marine carries just one-half of one percent of global trade.

An ever-diminishing fleet means fewer job opportunities. Often, captains will take a first- or second-mate position on a boat to earn a paycheck. When oil prices dropped last year, petroleum companies reduced output, requiring fewer tankers and barges, and fewer crews to helm them. Mariners took another hit; good-paying jobs in the merchant marine protected by American labor laws are scarce indeed.

In this climate, Davidson was angling for a promotion. To comply with new emissions regulations in the Caribbean, TOTE had ordered a pair of liquid natural gas ships to replace its three aging vessels—El Morro, El Yunque, and El Faro—and Davidson hoped to captain one of these. He interviewed for the position in May, and was awaiting an answer when he arrived in Jacksonville in September. If Davidson didn’t get the promotion, he would probably follow the old boat through the Panama Canal back to Alaska, where it was slated to do the Northwest route once again. Michael Holland had already been told that he’d join the El Faro on its West Coast run in the spring of 2017. That was a long way from Maine.

In fact, TOTE wanted younger captains to helm its gleaming LNG Caribbean fleet. That makes sense, a veteran mariner tells me. “I’ve seen it’s much harder to train experienced captains for these vessels. What you need is video game experience. With non-feedback of a vessel, it’s more intuitive.” Besides, he adds, “knowing how to run an antique steam plant, not many captains can handle that kind of vessel. TOTE probably decided Davidson was more valuable in Alaska.” TOTE had identified its LNG captains, but probably hadn’t yet notified Davidson that he was not one of them.

On Wednesday afternoon, a day after the El Faro left port, former second mate Charles Baird was at home in South Portland watching the Weather Channel, and what he saw of the developing storm worried him. He texted his concerns to Davidson, who at that point was still close enough to the coast to get cell service. Like all deck officers, Baird knew that captains ultimately decide the route, but there’s often room for debate. Charlie Baird was navigating when Davidson took the same inland route during tropical storm Erika. A former first mate of the El Faro told me, “He was the one who’d convinced him to go inland.” He adds, “I challenged the masters all the time. I said, ‘Captain, you need to take the old Bahama channel.’ I said, ‘I’m putting it on you.’ You gotta threaten them.”

This time, on land and off-duty, Baird’s powers of influence were limited.

Davidson assured Baird that he was aware of the storm. Hurricanes were almost always pulled north at some point before hitting the Caribbean island chain, and a Category 4 hurricane hadn’t tracked through the Bahamas since 1866. But Joaquin was taking its time; its path defied the odds.

Later that day, an increasingly concerned Baird texted Davidson again: What was the captain’s plan for avoiding the storm? Davidson replied that he was heading along the normal route at full steam (20 knots), and would sail under the system. Baird followed up, reminding Davidson of the escape routes available to him—the channels cut between the islands that would get him to the lee side if he found himself in trouble.

Twelve hours later, Joaquin had inched southwest while escalating to category 3—a major hurricane with winds up to 129 miles per hour—while the El Faro continued on its collision course with the storm. Now the ship was east of the Bahamas as Joaquin closed in.

Captain Kevin Stith was steering El Faro’ssister ship back up to Jacksonville and didn’t like what he saw. He was on the other side of Joaquin, closer to Puerto Rico, when he sent an email via satellite to Davidson to report that he’d just recorded 100-mile-per-hour winds. He warned him about the errant NHC forecast, and asked about his plans.

In his testimony, Stith said that Davidson replied that he had been watching the storm, had altered his route southerly; he expected to be on the back side of the hurricane in a few hours. But GPS tracking later revealed that Davidson hadn’t changed course. In fact, Davidson continued full steam ahead on a straight southeastern course up to the end.

During the hearings, Davidson was described by those who worked with him as conscientious, if not hands-on. He wasn’t deeply involved with the minutiae of ship operations; like many captains, he relied on the other deck officers—like Danielle—to be his eyes and ears. Stith, who frequently served as Davidson’s first mate before becoming master of the El Yunque, testified,“I did not see him on deck often. Maybe twice during my time with him.”

But Davidson’s cautiousness may have gotten him into trouble with employers in the past. Some news services reported that he had lost his previous petroleum company job because he’d elected to have his ship towed to port when it developed steering problems. Just a month before his final voyage, he’d rerouted the El Faro to avoid Tropical Storm Erika. After the El Faro sunk, experienced mariners online often theorized that TOTE had chewed out Davidson for this longer voyage, which would have cost the company time and fuel.

Like any company, privately owned TOTE needed to be profitable. In the early 2000s, it played a cutthroat game of chicken with two other U.S.-flagged transportation companies to monopolize the Puerto Rican route, a major run protected by the Jones Act. In an attempt to bankrupt each other, the three carriers deliberately cut their shipping prices to unsustainable levels, and TOTE, along with Horizon, emerged victorious.

Eliminating the competition wasn’t enough to satisfy TOTE’s executives. In 2008, a federal antitrust investigation uncovered a years-long price-fixing scheme that the two surviving companies had worked out to ensure that each made money from the Puerto Rican route. Both companies pled guilty and paid millions of dollars in fines. High-level executives from TOTE and Horizon went to jail. TOTE restructured and cut management.

It’s possible that this history, combined with his need to impress TOTE, colored Davidson’s judgment when confronted with a storm as he steamed south in the Atlantic Ocean.

Then again, it’s possible that Davidson didn’t understand what he was up against. Stith says that when he served as Davidson’s first mate, he observed that the captain relied heavily on the Bon Voyage weather reporting system, a proprietary service paid for by TOTE. “I think that was probably his primary resource; it had been proven over the years reliable,” he said during his testimony. “I think in our conversations he had full faith in that Bon Voyage System.”

At the hearings, Bon Voyage representatives revealed that they generally repackaged National Weather Service forecasts, a data-inputting process that took several hours after the original report had been issued. Their predicted trajectory for Hurricane Joaquin, sent out on September 30, was as much as 21 hours old and 500 nautical miles off.

Slow-moving hurricanes are hell for mariners. With hours and hours of high winds and high seas, even the saltiest sailors get seasick as the enormous boat rolls, dips, rises, and slams down into the troughs of the waves. “It’s a big danger,” testified Hearn, who’d been at sea during Hurricane Sandy. “When you’re in the grip of heavy seas for a longer period of time than a front, my experience is, once you start fighting weather, cargo lashings come loose, and there’s the fatigue of crew. More than 24 hours of that, the cargo is in danger. It’s a hazard to go out because the cargo is heavy and could crush a person.”

One former El Faro first mate told me, “In rough conditions, the first thing you do is throw up. All get seasick, plus you’re scared, as the seas are breaking over, with the ship rolling, making its own wave.” He’d worked with Danielle—he was very fond of her, called her Dani—since she was a cadet. He was furious that the El Faro had taken her into the storm.

Joaquin was the slow and powerful storm all mariners dread. As the El Faro approached the Category 3 hurricane, Danielle and the crew tried to hang on as the vessel rose and fell, struggling to power through the high seas, straining cargo lashings to the point where some may have given way.

In huge swells, its massive propeller would have come in and out of the waves, putting excessive strain on the 40-year-old steam engine trying to keep pace. Hearn said, “If you’re slamming your stern out of the water, then the boat settles in the next trough of a wave. With the force of tonnage, it slams. It’s a pounding that could be catastrophic to the machinery.” Hearn describes a dire scene: “If your stern is slamming, you need to get into a head sea and reduce the speed. You risk [propeller] cavitation [a violent reduction in pressure that sends shock waves through the shaft] if the prop comes out of the water. You can feel the vibration when it does.”

Photo Credit : National Transportation Safety Board via Associated Press

Down in the engine room, Michael doubtless labored with his fellow engineers to keep the old plant running, trying not to get knocked into the hot steam pipes all around him as the ship’s prow rose and then plummeted. One problem they faced was clogging of the fuel lines. During voyages, chunks of the asphalt-like fuel, called bunk, settle to the bottom of the fuel tanks, and that sediment can get shaken free by the sea’s churn. It’s likely that someone in the engine room spent a sleepless night clearing the fuel-line filters dozens of times an hour. It might have been impossible to keep up. At some point near dawn, the engine went out.

Without propulsion, the enormous El Faro was at the mercy of an angry ocean, slammed by waves, thrashed by winds. It was particularly vulnerable because it had been designed with a broad lower deck that served as a parking lot for the cars and trucks it carried. If water got down there through an open hatch, or worse, through the enormous door cut in the hull for roll-on/roll-off loading, she could quickly destabilize and sink.

At 7 a.m. on October 1, Davidson made the emergency call to shore. His voice on the recording is eerily calm. They’d lost propulsion. They were at a 15-degree list. They were taking on water. There was a breach in the hull. About half an hour later, the black box recorded Davidson calling for his crew to abandon ship. But they had little chance for survival in open lifeboats and rafts.

On land, the Coast Guard and TOTE’s designated contact discussed the severity of the El Faro’s situation. No one at TOTE had been following the El Faro; Davidson’s emergency call came out of the blue. Plotting his position, the U.S. Coast Guard was alarmed to discover that the ship was just 20 miles from Joaquin’s eye. The storm would soon escalate to Category 4.

But that, and the automated distress calls, were the final messages from the El Faro.

In the wee hours of October 1, Danielle sent her mother an email. She’d told Laurie about harrowing hurricanes before, but always after the fact. This time, she wrote, “Don’t know if you’ve been hearing, we’re in really bad seas and really bad wind and heading straight for the hurricane.”

Then she wrote, “Give my love to everyone.”

“As soon as I read that, I knew we were done for,” Laurie tells me. “She never, ever, ever, ever would write Love, Danielle or anything like that. She wasn’t cold-hearted, she just had a really hard time saying—like I always had to finish the phone call, ‘Love you,’ and she’d say, ‘Love you, too.’ She would never be the one to generate the Love you, Mom type thing, you know what I mean? And for her to write on the email, ‘Give my love to everyone,’ I knew we were, we were, we were screwed.

“So when I got the phone call saying that they’d lost communication with the ship, ‘We’re sending people to look,’ I knew then and there that the ship went down. There was no doubt in my mind. I didn’t have to wait the seven damn days of them searching. I knew damn well that the ship went down.”

Strong and resilient, like so many parents of New England mariners before them, Michael Holland’s mom, Deb, and Laurie were among the first relatives of the lost crew to accept that the El Faro had been lost. During the agonizing week in Jacksonville while the Coast Guard combed the ocean for the survivors—and then any evidence of the enormous ship—they became the public face of maritime grief.

They worked with the Red Cross to set up a Facebook page with regular updates for anyone connected to the El Faro. They gave TV interviews to ensure that the human side of the tragedy wasn’t lost in its telling. Pictures of Michael, and Danielle—smiling in her crisp white uniform, her hair tucked beneath her hat—appeared everywhere.

After the final meeting in Florida, when relatives were told that the search was finished, Deb, her husband, and Kelsea navigated rush-hour traffic to get to the beach. Eight years before, Deb had driven to Castine to see Michael off before he sailed to Europe aboard the Maine Maritime Academy’s training ship. Now she was saying a different goodbye.

Holding her shoes, she walked to the water to be closer to her son. She said, “We had this beautiful moment on the beach where Kelsea and I just felt Michael.

“We went in the water, and obviously just lost it, and cried and hugged. I was crying, really crying hard,” she says. “And I was leaning down and then this huge wave came and got us soaking wet. And I was like, All right, Michael, I get it, I get it. OK, I’ll stop.”

UPDATE:

On December 13, 2016, the National Transportation Safety Board released a 510-page transcript of conversations recorded on the El Faro’s bridge during the cargo ship’s final hours. The transcript, taken from audio recovered from the ship’s data recorder, is the longest ever produced by the NTSB. It can be read in full here: http://dms.ntsb.gov/public/58000-58499/58116/598645.pdf

Correction: Charlie Baird’s texts were sent to Captain Davidson on September 29 while the El Faro was still docked at Jacksonville.

SEE MORE:El Faro Update