Yankee

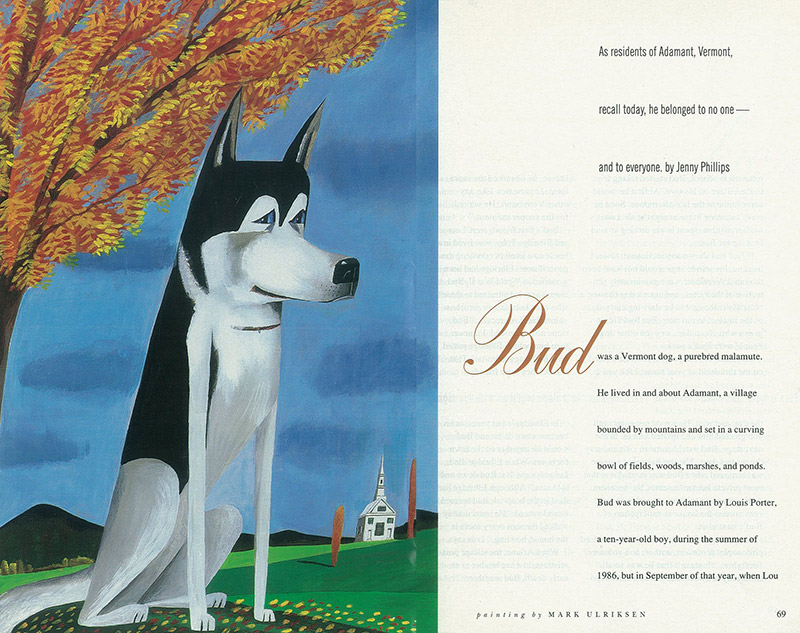

Bud | A Vermont Dog

Bud was a Vermont dog, a purebred malamute. He lived in and about Adamant, a village bounded by mountains and set in a curving bowl of fields, woods, marshes, and ponds. Bud was brought to Adamant by Louis Porter, a ten-year-old boy, during the summer of 1986, but in September of that year, when Lou […]

Bud was a Vermont dog, a purebred malamute. He lived in and about Adamant, a village bounded by mountains and set in a curving bowl of fields, woods, marshes, and ponds. Bud was brought to Adamant by Louis Porter, a ten-year-old boy, during the summer of 1986, but in September of that year, when Lou returned to school, Bud started taking trips to the village on his own. At first he would come home in the late afternoons. Soon he wasn’t coming home at night at all. Louis’s mother, Ruthie, spent hours driving around looking for Bud.

If Bud had shown any inclination toward hunting, his wanderings would not have been tolerated. Vermonters are passionately protective of their deer, and even a dog chasing a butterfly is thought to be showing early signs of the instinct to run deer. But Bud didn’t give a whit about deer, or even other dogs. People were Bud’s pack.

Bud liked to visit people. He would stand on the threshold of your home, look you in the eye, and wait. He would not enter until you greeted him and invited him in. In the next stage, Bud would come to visit and stay for several days. The last barrier of reserve was removed when Bud was invited into that most private human sanctum, the bedroom. At this stage, special bowls and food were seen around the house in anticipation of Bud’s next visit.

According to Forrest Davis, a local retired philosophy professor, author, and volunteer firefighter, “It wasn’t that he was so all-fired easy to know. There was a certain politesse; he observed the more formal courtesies, like any other Vermonter. He waited for the proper moment.”

Bud’s first friends were Lois and Elbridge Toby, who lived in a house on a knoll overlooking the general store. Elbridge had been wounded in World War II. Bud always seemed attracted to those who were hurt, sad, or somehow vulnerable. Lois recalls, “Bud came nosing around. I’d never seen him before. Elbridge patted him. Bud wagged his tail. That was it. They were friends.”

In Elbridge’s last years, as he became more ill, he and Bud would lie together on the lawn for hours. When Elbridge died, Lois says she “sat Bud down and told him.” Although Elbridge had died in the hospital, Bud seemed to understand. “He immediately walked through every room in the house, howling,” Lois says.

When Arlene, the village postmistress, lost her brother to an early death, Bud was there. “I was devastated, but I didn’t want to share my grief with anyone in the village. Every day, after I sorted the mail, it was my custom to walk home. Throughout that spring, Bud would meet me at the store when I was finishing. Then he would walk up the hill with me. I would sit in the window and cry, just sobbing. Buddy would sit there beside me and listen to my crying. Sometimes I would put my arm around him. It was so helpful.”

Alison Underhill is a staunch defender of wildlife and a skeptic about dogs. She used to call Ruthie to complain whenever she saw Bud roaming loose. But Bud won her over. “Bud belonged to himself. He was all of ours, but we were also his. He was aloof and independent, not needy like many dogs. He seemed to let people know, ‘You may pat me if you like,’ yet he had a way of showing real affection and caring. He let you know that he visited you because he wanted to be with you. He chose you. I always felt honored when he came to visit.”

Dogs were not allowed in the community store back then, but gradually the rules were relaxed for Bud until, at some point, he was expected and welcome. On cold days, he spent hours in front of the woodstove, a handy place for him to meet new owners and generally work his social traplines.

Tim Cook, whose sister Polly manages the general store, moved into a cabin in the woods on the quarry road a half mile from the village. Tim was 85 percent deaf and blind from a progressive neurological condition. By living in a cabin without water or electricity, Tim was fending off the realization that he couldn’t live independently much longer. Bud must have noticed Tim’s struggle because he became a self-made seeing-eye dog, walking back and forth with Tim, guiding him away from traffic and obstacles.

The amazing thing was that Bud could maintain such a tight schedule of duties, obligations, and social calls. Over the years, Bud knit the village together with his zigzag trail. One resident said, “We all had this dog in common. We called around on the phone to see what he was doing.” In the end, nobody really owned Bud. He became a public institution.

Dr. Eleanora Sense, at 100-plus years old, was one of the deans of the Adamant Music School, which draws piano students and masters from around the world every summer. She is described by those who remember her as imperious and magisterial, with a daunting ability to control and dominate those around her. The story goes that Eleanora would bring a string when she walked down to the general store. If Bud happened to be at the store, Eleanora would loop her string through Bud’s collar and lead him to her cabin. Bud would spend a few days and nights under her tutelage. It is also said that she and her willing prisoner enjoyed tea and Lorna Doones together. On one Fourth of July, Eleanora led Bud in the village parade with a crown of flowers on his head.

It was on a wintry walk with Marion Parauka and Lois Toby up by the county road that Bud first showed signs of kidney disease. “Buddy took his first spell over by Mary Radigan’s house. He fell down in the road for no apparent reason,” Lois remembers. The local veterinarian prescribed a special diet and, pretty soon, village houses and the general store were stocked with cans of the right food. The store bulletin board carried alerts on Bud’s condition. Word spread that people should stop feeding him cookies and ice cream: Bud needed protein. People took cooked meat, often moose meat, to the store for Bud when he stopped by.

Later, Bud’s declining health necessitated that he be administered medication every day. A sign-up sheet was posted in the store with instructions on when and how to give Bud his medication. Bud began to spend more time in front of the general store’s woodstove as he became less able to work his territory. He shifted his locations less frequently, and he lengthened his visits.

When Ruthie noticed that Bud was failing to the point that he could no longer maintain his customary lifestyle, she took him to a homeopathic veterinarian and left him there for several days of treatment. “We were just trying to help Bud feel more comfortable, but when we brought him home, he was so sick he couldn’t even walk. We knew we were going to have to put him to sleep. We decided we would give Bud a few final days so everyone could come and say good-bye.” Word spread quickly. Someone posted a notice: “Buddy is dying.”

Ruthie recalls that over the next few days there was a steady stream of Bud’s people. “There were so many people I didn’t even recognize, much less know. But Bud knew everyone.”

Some chose not to visit Bud’s deathbed. As one person put it, “I didn’t want to embarrass Bud. He had had such dignity in his life.

On February 24, 1996, Ruthie’s journal reads, “Buddy can’t even stand. His face is all swollen and he can’t stop shivering.” On February 28 she wrote, “Today is the day. My heart is aching. I found a little girl sitting and sobbing by Bud’s side. I had never seen her before.” That afternoon, the veterinarian was called, and Bud died in Louis’s kitchen surrounded by a small circle of family and friends.

They brought Bud’s body down into the village at nightfall on March 3. An icy wind blew fresh snow in swirling eddies. His body was shrouded in a blanket and laid across the back seat of an old red sedan. As the car slowly wound its way along the steep, twisting dirt road, a crowd of Bud’s friends, lining both sides of the road, was caught and held by its headlights. Next to a frozen pond and beaver dam was an open grave bordered by mounds of loose dirt. The body was lifted out of the car, gently lowered into the grave, and then covered with a brilliant red scarf. The villagers silently took turns shoveling dirt into the grave. Someone murmured, “We’re sure going to miss him.”

Bud was a Vermont dog, a purebred malamute. He lived in and about Adamant, a village bounded by mountains and set in a curving bowl of fields, woods, marshes, and ponds. Bud was brought to Adamant by Louis Porter, a ten-year-old boy, during the summer of 1986, but in September of that year, when Lou returned to school, Bud started taking trips to the village on his own. At first he would come home in the late afternoons. Soon he wasn’t coming home at night at all. Louis’s mother, Ruthie, spent hours driving around looking for Bud.

If Bud had shown any inclination toward hunting, his wanderings would not have been tolerated. Vermonters are passionately protective of their deer, and even a dog chasing a butterfly is thought to be showing early signs of the instinct to run deer. But Bud didn’t give a whit about deer, or even other dogs. People were Bud’s pack.

Bud liked to visit people. He would stand on the threshold of your home, look you in the eye, and wait. He would not enter until you greeted him and invited him in. In the next stage, Bud would come to visit and stay for several days. The last barrier of reserve was removed when Bud was invited into that most private human sanctum, the bedroom. At this stage, special bowls and food were seen around the house in anticipation of Bud’s next visit.

According to Forrest Davis, a local retired philosophy professor, author, and volunteer firefighter, “It wasn’t that he was so all-fired easy to know. There was a certain politesse; he observed the more formal courtesies, like any other Vermonter. He waited for the proper moment.”

Bud’s first friends were Lois and Elbridge Toby, who lived in a house on a knoll overlooking the general store. Elbridge had been wounded in World War II. Bud always seemed attracted to those who were hurt, sad, or somehow vulnerable. Lois recalls, “Bud came nosing around. I’d never seen him before. Elbridge patted him. Bud wagged his tail. That was it. They were friends.”

In Elbridge’s last years, as he became more ill, he and Bud would lie together on the lawn for hours. When Elbridge died, Lois says she “sat Bud down and told him.” Although Elbridge had died in the hospital, Bud seemed to understand. “He immediately walked through every room in the house, howling,” Lois says.

When Arlene, the village postmistress, lost her brother to an early death, Bud was there. “I was devastated, but I didn’t want to share my grief with anyone in the village. Every day, after I sorted the mail, it was my custom to walk home. Throughout that spring, Bud would meet me at the store when I was finishing. Then he would walk up the hill with me. I would sit in the window and cry, just sobbing. Buddy would sit there beside me and listen to my crying. Sometimes I would put my arm around him. It was so helpful.”

Alison Underhill is a staunch defender of wildlife and a skeptic about dogs. She used to call Ruthie to complain whenever she saw Bud roaming loose. But Bud won her over. “Bud belonged to himself. He was all of ours, but we were also his. He was aloof and independent, not needy like many dogs. He seemed to let people know, ‘You may pat me if you like,’ yet he had a way of showing real affection and caring. He let you know that he visited you because he wanted to be with you. He chose you. I always felt honored when he came to visit.”

Dogs were not allowed in the community store back then, but gradually the rules were relaxed for Bud until, at some point, he was expected and welcome. On cold days, he spent hours in front of the woodstove, a handy place for him to meet new owners and generally work his social traplines.

Tim Cook, whose sister Polly manages the general store, moved into a cabin in the woods on the quarry road a half mile from the village. Tim was 85 percent deaf and blind from a progressive neurological condition. By living in a cabin without water or electricity, Tim was fending off the realization that he couldn’t live independently much longer. Bud must have noticed Tim’s struggle because he became a self-made seeing-eye dog, walking back and forth with Tim, guiding him away from traffic and obstacles.

The amazing thing was that Bud could maintain such a tight schedule of duties, obligations, and social calls. Over the years, Bud knit the village together with his zigzag trail. One resident said, “We all had this dog in common. We called around on the phone to see what he was doing.” In the end, nobody really owned Bud. He became a public institution.

Dr. Eleanora Sense, at 100-plus years old, was one of the deans of the Adamant Music School, which draws piano students and masters from around the world every summer. She is described by those who remember her as imperious and magisterial, with a daunting ability to control and dominate those around her. The story goes that Eleanora would bring a string when she walked down to the general store. If Bud happened to be at the store, Eleanora would loop her string through Bud’s collar and lead him to her cabin. Bud would spend a few days and nights under her tutelage. It is also said that she and her willing prisoner enjoyed tea and Lorna Doones together. On one Fourth of July, Eleanora led Bud in the village parade with a crown of flowers on his head.

It was on a wintry walk with Marion Parauka and Lois Toby up by the county road that Bud first showed signs of kidney disease. “Buddy took his first spell over by Mary Radigan’s house. He fell down in the road for no apparent reason,” Lois remembers. The local veterinarian prescribed a special diet and, pretty soon, village houses and the general store were stocked with cans of the right food. The store bulletin board carried alerts on Bud’s condition. Word spread that people should stop feeding him cookies and ice cream: Bud needed protein. People took cooked meat, often moose meat, to the store for Bud when he stopped by.

Later, Bud’s declining health necessitated that he be administered medication every day. A sign-up sheet was posted in the store with instructions on when and how to give Bud his medication. Bud began to spend more time in front of the general store’s woodstove as he became less able to work his territory. He shifted his locations less frequently, and he lengthened his visits.

When Ruthie noticed that Bud was failing to the point that he could no longer maintain his customary lifestyle, she took him to a homeopathic veterinarian and left him there for several days of treatment. “We were just trying to help Bud feel more comfortable, but when we brought him home, he was so sick he couldn’t even walk. We knew we were going to have to put him to sleep. We decided we would give Bud a few final days so everyone could come and say good-bye.” Word spread quickly. Someone posted a notice: “Buddy is dying.”

Ruthie recalls that over the next few days there was a steady stream of Bud’s people. “There were so many people I didn’t even recognize, much less know. But Bud knew everyone.”

Some chose not to visit Bud’s deathbed. As one person put it, “I didn’t want to embarrass Bud. He had had such dignity in his life.

On February 24, 1996, Ruthie’s journal reads, “Buddy can’t even stand. His face is all swollen and he can’t stop shivering.” On February 28 she wrote, “Today is the day. My heart is aching. I found a little girl sitting and sobbing by Bud’s side. I had never seen her before.” That afternoon, the veterinarian was called, and Bud died in Louis’s kitchen surrounded by a small circle of family and friends.

They brought Bud’s body down into the village at nightfall on March 3. An icy wind blew fresh snow in swirling eddies. His body was shrouded in a blanket and laid across the back seat of an old red sedan. As the car slowly wound its way along the steep, twisting dirt road, a crowd of Bud’s friends, lining both sides of the road, was caught and held by its headlights. Next to a frozen pond and beaver dam was an open grave bordered by mounds of loose dirt. The body was lifted out of the car, gently lowered into the grave, and then covered with a brilliant red scarf. The villagers silently took turns shoveling dirt into the grave. Someone murmured, “We’re sure going to miss him.”

***

An adamant music school postcard with Bud’s picture on it is still sold in the general store today. And a granite gravestone, paid for by donations collected in the store, still marks Bud’s grave by the upper Adamant Pond dam. An old dog named Eric now enjoys Bud’s spot in front of the woodstove. Some say that Eric is trying to take Bud’s place. But everyone agrees that no dog can really ever do that. Excerpt from “Bud,” Yankee Magazine, December 1999.