Fruitlands and State of Grace | Book Review

The word eccentric means, literally, “off-center.” These two books examine New Englanders who, like all true eccentrics, never thought of themselves as strange; it’s everyone else who’s off-center. Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia, by Richard Francis, is the story of a motley band of 19th-century idealists–deeply influenced by Transcendentalists such as […]

The word eccentric means, literally, “off-center.” These two books examine New Englanders who, like all true eccentrics, never thought of themselves as strange; it’s everyone else who’s off-center.

Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia, by Richard Francis, is the story of a motley band of 19th-century idealists–deeply influenced by Transcendentalists such as Emerson–who in 1843 moved to a rundown farm in Harvard, Massachusetts. There, with a handful of followers, Francis says, “they tried to live a self-sufficient life, eating their own produce and wearing homemade linen clothes. (One of them believed in wearing nothing at all, in imitation of Adam and Eve.)”

Francis, who has written both history and fiction, brings a novelist’s eye to the often-comical story of what he calls a “Transcendental zoo.” On one occasion, Abigail Alcott, the long-suffering wife of the colony’s leader, Bronson Alcott, sent one of her daughters to persuade the philosophers to stop talking and start working. She came back to report, “Mamma, they have begun again!” That little girl happened to be Louisa May Alcott, later the author of Little Women, in which her mother is portrayed as wise and loving, and her father as largely absent, in both mind and body. The effort to “reproduce Perfect Men,” as Alcott put it, without sexual intercourse lasted only 14 months, the final 7 of them at Fruitlands, ending in bankruptcy and bitterness.

But Francis avoids the temptation to sneer. “Despite their eccentricity, many of the Fruitlanders’ ideas ring bells today,” he writes, acknowledging their prescient notions of ecology, their opposition to slavery, and their support of women’s rights.

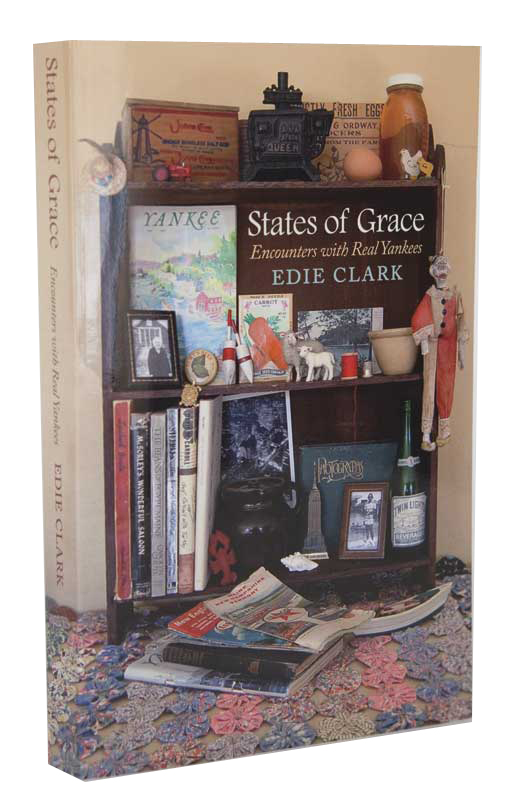

By contrast, the subjects of Edie Clark’s States of Grace: Encounters with Real Yankees have more modest ambitions. Though not famous, they’re not unsung: Shirley Center, Massachusetts, once celebrated Melvin P. Longley Day, to honor a local farmer who knew all there was to know about wild grasses; Bill Souza’s scale-model cars and a village made entirely of scrap aluminum and beer cans reside proudly at a museum in Portsmouth, Rhode Island; Thelma Hanson’s quilt celebrating the life of bear trainer Murray Clark is still on display at Clark’s Trading Post in Lincoln, New Hampshire. Eccentric they may be, but all possessed a deep and abiding passion at the center of their lives.

–Tim ClarkFruitlands by Richard Francis (Yale University Press; $30)

States of Grace by Edie Clark (Benjamin Mason Books, P.O. Box 112, Dublin, NH 03444; $19.95 plus $4 shipping)