Yankee

Art and Artists of New England Islands | Drawn to Islands

The beauty of the New England islands has inspired an enduring legacy of artists and fine art, some 150 years in the making.

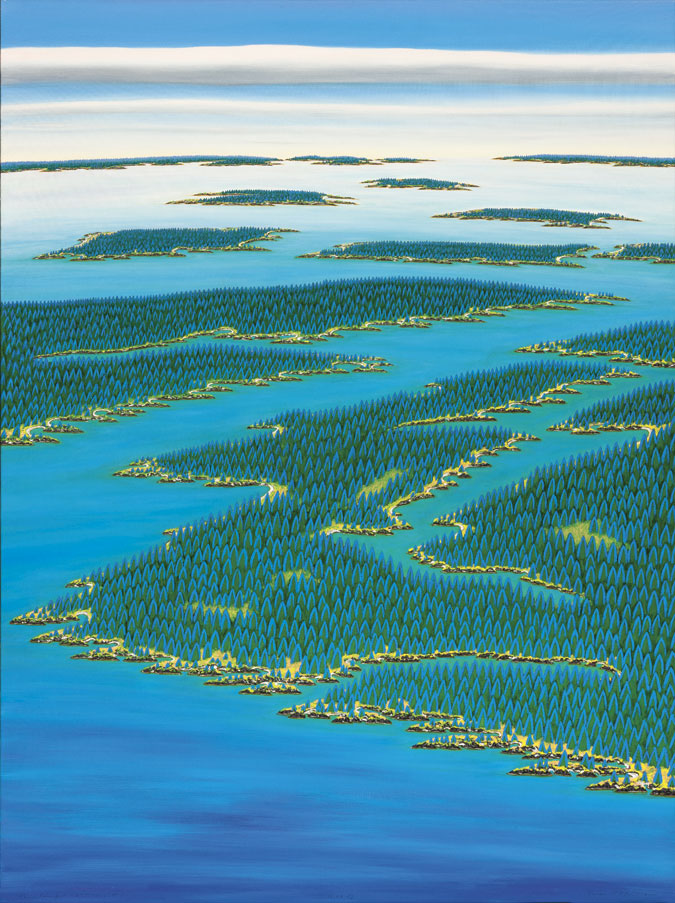

“Receding Islands #1” by Eric Hopkins, 2012. The artist is known for his vibrant depictions of natural and geographical forms.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Eric Hopkins“The whole coast along here is iron bound– threatening crags, and dark caverns in which the sea thunders,” wrote painter Thomas Cole on September 3, 1844, as he explored Maine’s Mount Desert Island for the first time. “The view of Frenchman’s Bay and islands is truly fine. Some of the islands, called Porcupines, are lofty and belted with crags which glitter in the setting sun. Beyond and across the bay is a range of mountains of beautiful aerial hues.”

In 1844, the bridge that connects the island to the mainland at Trenton was only seven years old, and the dramatic landscape of Mount Desert Island, the only place along the East Coast where mountains rise straight out of the sea, had yet to be discovered by the masses. Cole, founding father of the Hudson River School, and the 19th-century artists who followed him to Maine’s most majestic island–among them, Frederic Church, Thomas Doughty, and Fitz Henry Lane–provided America with so vivid a vision of Mount Desert’s natural wonders that journalists, sportsmen, and rusticators soon followed. By the 1880s, Mount Desert, the village of Bar Harbor in particular, was well on its way to becoming the thriving summer resort it still is today.

New England’s island landscapes differ markedly from one to another, ranging from the high, hard, stony coast of Maine to the low, soft, sandy shores of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The retreating Laurentide ice sheet deposited Block Island, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and Cape Cod as glacial outwash and terminal moraines some 15,000 years ago, while the rockier northern islands from Mount Desert to Vinalhaven, North Haven, Monhegan, and the Isles of Shoals were formed by glacial erosion of the underlying bedrock, already bucked and folded. And just as artists paint, draw, print, and sculpt in a wide variety of styles, so each island landscape seems to have its own art history.

The nine little Isles of Shoals on the Maine/New Hampshire border, for instance, are closely associated with American Impressionist Childe Hassam, who came to Appledore Island in 1890 at the invitation of poet Celia Thaxter, one of his former students. Thaxter’s family ran the inn on the island, and Thaxter herself became the center of a summer salon.

On Appledore, Hassam painted Thaxter’s gardens, the island’s low ledges, and the high horizons of the Atlantic Ocean, all in a felicitous palette of sunny oils. On Appledore, as well, Hassam, who’d begun his artistic career as an illustrator and watercolorist, made the first sale of what would become a celebrated series of works in his new medium to composer George Chadwick. The Isles of Shoals, Hassam wrote, were where “I spent some of my pleasantest summers [and] where I met the best people in the country.”

The “best people” to whom he referred were summering aristocrats, but artist Rockwell Kent was attracted to rugged Monhegan as much by the local fishermen as by the island’s monumental landscape. In his 1955 autobiography, It’s Me, O Lord, Kent recalled his first visit, in 1905, by extolling “those hardy fisherfolk, those men garbed in their sea boots and their black or yellow oilskins, those horny-handed sons of toil–shall I go on? No, that’s enough.”

Kent had followed his mentor, Robert Henri, out to Monhegan, the coastal island that eventually evolved into one of the most fully developed summer art colonies in New England. What Monhegan artists tended to look for was authenticity: hardworking people living close to nature in a wild and unspoiled place. Among the artists associated with Monhegan over the years have been George Bellows, Leo Brooks, Jay Hall Connaway, Lynne Drexler, James Fitzgerald, Alan Gussow, Edward Hopper, Eric Hudson, John Hultberg, Elena Jahn, Frances Kornbluth, Leon Kroll, Michael Loew, Hans Moller, Zero Mostel, Reuben Tam, Andrew Winter, and James Browning Wyeth.

Jamie Wyeth, son of Andrew and grandson of N.C., first visited Monhegan as a teenager, and on his 21st birthday, in 1967, he purchased Rockwell Kent’s seaside cottage there. Notoriously private, Wyeth grew uncomfortable with the presence of so many artists and art lovers on Monhegan and eventually sought solitude in the lighthouse on his own private island (which he purchased from his parents), Southern Island, off Tenants Harbor. He now paints on both islands. “One is people. The other is not. It’s that simple,” Wyeth says of his island art. On Monhegan, with its thriving population of summer residents and daytrippers, he paints the social life, and especially the lives of children, while on Southern he mostly paints landscapes, seascapes, and seabirds. “Islands tend to give me focus. They sure do eliminate things,” Wyeth says. “I can stand on Southern Island and see the borders of my world.”

—

The roots of many New England island art communities seem often to lie in New York cultural institutions, as urban artists over the years have sought cooler rural locales to escape summer in the city. A case could be made, for example, that the Art Students League of New York (ASL) colonized Martha’s Vineyard. Painter Vaclav Vytlacil, a teacher at the ASL and one of the founders of the American Abstract Artists group, brought Modernism to bear on island imagery during the 40 years he summered in Chilmark. And Thomas Hart Benton, the great American Regionalist painter and another ASL instructor, credited the social realism of Chilmark with inspiring his first forays into figurative work.

“Like all people who live in near-isolation for long periods of the year,” Benton wrote, “the Chilmarkers were friendly, glad to talk and visit at the general store and at their homes. Finding willing models among them, I began in the summer of 1920 my first essays in American genre painting.”

Benton, a hard-drinking Midwesterner, is still remembered on the Vineyard for bringing another hard-drinking Midwesterner to the island: Jackson “Jack the Dripper” Pollock, perhaps America’s greatest Abstract Expressionist painter. Pollock was a guest of the Bentons for several summers on Martha’s Vineyard. Arriving unannounced one summer, so the story goes, he proceeded to purchase a bottle of gin, rent a bicycle, and set out to pedal the almost 20 miles from Oak Bluffs to Chilmark. As the notorious Pollock became more and more intoxicated, he began chasing local girls on his bike, inevitably crashing and spending the night in the island jail. In his autobiography, Benton pronounced the episode “so hilarious that it was impossible to take his case seriously.”

Another ASL teacher, landscape artist Frank Swift Chase, came ashore on Nantucket in 1920, the same year Benton landed on Martha’s Vineyard. While more widely known artists such as Eastman Johnson, George Inness, and William Trost Richards had painted on the island earlier, Chase, by virtue of operating a painting summer school on the island until 1945, became known as the “dean of Nantucket art.” Chase’s students included Anne Ramsdell Congdon, Emily Leamon Hoffmeier, Harriet Lord, Elizabeth Saltonstall, Ruth Haviland Sutton, and Isabelle Hollister Tuttle, all mainstays of the Artists Association of Nantucket in the mid-20th century.

Cooper Union, another New York art school, was the tie that bound several of the artists drawn to the Cranberry Isles–lovely, low islands forming the southerly view from the mountains of Mount Desert and Acadia National Park. Cooper Union alums Ashley Bryan, Marvin Bileck, Emily Nelligan, Louis Finkelstein, and Gretna Campbell formed the nucleus of the little Cranberry art colony, along with painters Dorothy Eisner, John Heliker, William Kienbusch, Robert LaHotan, and Carl Nelson, several of whom also had ASL connections.

“Great Cranberry Island had a lively community of artists from the 1950s through the 1970s,” notes Henry Finkelstein, son of Louis Finkelstein and Gretna Campbell, “but the idea of it being an ‘artists’ colony’ doesn’t sound right to me. Artists were simply a fixture of the place, as were fishermen and some summer families going back 50 years by then.”

Many of the Cranberry artists were Expressionists, translating island imagery into personal abstract idioms, as does Henry Finkelstein today. Finkelstein claims Cranberry as a birthright, as do painter David Little and poet/art critic Carl Little, who inherited their uncle William Kienbusch’s island home.

Finkelstein sounds an all-too-familiar refrain when he says, “Someone scraping by as a young artist couldn’t afford to settle there, although, fortunately, artists can now come and at least visit through the Heliker-LaHotan Foundation.”

—

Island properties, once financially accessible owing to their remoteness, have become so expensive that struggling artists are often priced out of the market. As a result, several New England islands now have artist residency programs. Painters John Heliker and Robert LaHotan bequeathed their Great Cranberry Island cottage so that mid-career artists could spend three to four weeks at a time working on the island they loved.

On Monhegan, Carina House offers five-week residencies to emerging Maine artists. On Maine’s Great Spruce Head Island, where painter Fairfield Porter and photographer Eliot Porter once summered and worked, their niece Anina Porter Fuller now makes this private family island available to a dozen artists each summer during Art Week. And on Nantucket, the Nantucket Island School of Design & the Arts (NISDA) makes its 10 Harbor Cottages available to artists of all kinds year-round at affordable rates. “NISDA offers the opportunity to experience historic Nantucket,” notes director Kathy Kelm, an island resident for 40 years, “and a place for artists to enjoy the island’s beauty and isolation for creative purposes.”

Artists looking for a more affordable island alternative might want to consider Rhode Island’s Block Island. It may lack the deep art history of some of the other islands, but painter Jessie Edwards, who represents some 35 Block Island artists in her gallery above the post office, says that the island has a lot to offer an artist. “Block Island still feels untouched,” she observes. “It still has its natural beauty and charm.”

—

The first artists on New England’s islands were essentially visual explorers. Then came the artist visitors, summer colonists, and settlers. But while the best island artists were all once “from away,” some of the best and best-known island artists are now homegrown.

Martha’s Vineyard native Allen Whiting is the island’s favorite son when it comes to art. His grandfather was a New York artist who married an island woman, so Whiting likes to say that he has “200 years’ worth of relatives next door” in the local cemetery.

Whiting operates the family farm and renders gentle island landscapes in the popular, brushy style of painterly realism. He sells his work through the Davis House Gallery at his home in West Tisbury. “I don’t think any place makes a painter,” Whiting says, but he does liken his good fortune in being born on Martha’s Vineyard to winning the lottery repeatedly. “Three-quarters of my success is due to growing up and painting in a resort that has been growing my whole life.”

Eric Hopkins grew up on North Haven Island in Penobscot Bay. His soaring, simplified aerial visions of the islands and the bay have become icons of contemporary Maine art. For many years he maintained a gallery next to the island ferry dock, but it’s now located on the mainland in downtown Rockland.

Over the past three years, Hopkins has been spending much of his time on Mount Desert, connected to artists such as Thomas Cole and Frederic Church through the sense of awe that island landscapes can inspire–a sense of living on the very edge of the land, sea, and sky. “Growing up, I was totally surrounded by and submersed in wonder,” Hopkins explains, effectively summing up the magical attraction of island life–not just for artists but for all of us. “There’s a sense of place … Sometimes I didn’t even know where I was, but I knew [that] if I walked in a straight line, I’d come to the shore and find my way. Islands are finite places. The Earth is just an island in space.”

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem