Antiques: Store Signs

Centuries before Nike introduced its signature swoosh, and Apple its nibbled pomme, the idea of branding — creating an iconic image and a distinct personality for a business — was simply old hat. It was called the “trade sign.” Early trade signs were America’s first attempt at branding, and a darned good one. The origins […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanCenturies before Nike introduced its signature swoosh, and Apple its nibbled pomme, the idea of branding — creating an iconic image and a distinct personality for a business — was simply old hat. It was called the “trade sign.”

Early trade signs were America’s first attempt at branding, and a darned good one. The origins of the trade sign may be traced back to ancient Rome, but gutsy colonial America injected a New World flavor into the concept. The late 18th century was a bustling time for the American merchant class. Eager to succeed, entrepreneurs took their competitive bravado to the street, ushering in a “golden age” of signmaking, the remnants of which are now prized examples of American folk art.

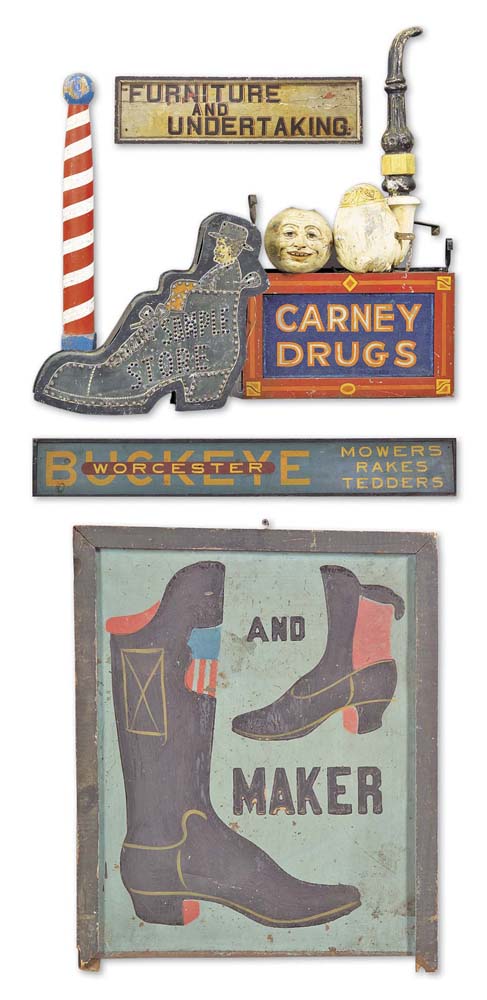

American trade signs fall into two general categories: 18th- to early 19th-century, and later 19th- to early 20th-century. The older the better for collectors. Earliest examples include inn, tavern, blacksmith, tinsmith, hatter, cobbler, apothecary, printer, and shop signs in the form of shields or placards, often double-sided, which hung on brackets off the side of an establishment. Signs were typically made of white pine, painted with a large image, few words, and often a date. Animals and political figures were popular themes for inn and tavern signs. Some wonderfully tongue-in-cheek shop signs were simply oversized versions of the products or services provided: a giant tooth, an enormous pair of eyeglasses, a great big boot. By the mid-19th century, signs were affixed horizontally across building fronts. Bold, often carved, lettering replaced much of the imagery.

Stephen Fletcher and Chris Barber, director and specialist, respectively, for Skinner’s American Furniture & Decorative Arts department, are devotees of the trade sign. “Trade signs not only offer visual appeal,” explains Barber, “but their words can strike a familiar chord with a collector: their name, the town where they live, their chosen profession. It adds a nice personal touch to a collection.”

“Trade signs were hung outdoors, so you’ll find that most examples have been repainted,” notes Fletcher. “Some have had only their lettering repainted many times over, creating a wonderfully raised, almost embossed, effect. A repainted surface is usually a red flag for diminished value, but not with trade signs, provided the repaint isn’t recent. Their value lies in their iconic appeal.”

Wannabe collectors should know that trade signs are pretty plentiful, even affordable. You’ll pay a few hundred dollars for a simple mid-19th century example; a few thousand for a large, colorful, intricately carved sign; and up to $200,000 for an early tavern sign in mint condition.

Reproductions abound, but skip them: They’re just too shiny, too bright, and too manufactured-looking to ever be confused with the real thing. Should you find yourself at an auction or flea market contemplating the purchase of an early trade sign, follow the simple yet brilliant advice of one modern-day brander: Just do it.

Catherine Riedel represents Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers of Boston. 617-350-5400, 978-779-6241; skinnerinc.com