Yankee

Silhouettes | Antiques & Collectibles

As a fashion statement, the chic and classic all-black look has been around for a long time; it predates Coco Chanel and Johnny Cash and transcends mere clothing styles. Universal in its appeal, black has been used throughout the ages to symbolize eternity, solemnity, elegance, and formality. A light-absorbing mass, black masks imperfections and swallows […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

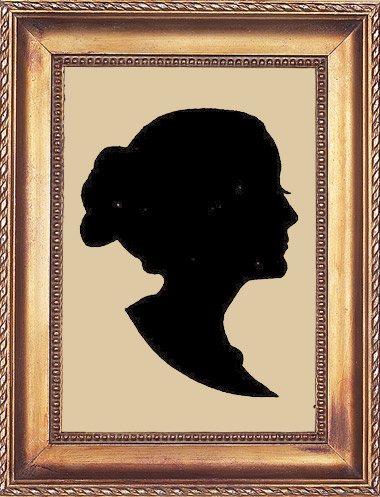

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan As a fashion statement, the chic and classic all-black look has been around for a long time; it predates Coco Chanel and Johnny Cash and transcends mere clothing styles. Universal in its appeal, black has been used throughout the ages to symbolize eternity, solemnity, elegance, and formality. A light-absorbing mass, black masks imperfections and swallows details. But that weightiness is also what gives black its clarity. When used delicately, black can feel as fine and crisp as script from a fountain pen; at its most powerful, it hits us as forcefully as a blacksmith’s anvil. It is these two opposite effects that are at visual play in the fashionable all-black art form known as Early American silhouettes.

Silhouettes are miniature portraits, either busts or full figures, in which the sitter’s profile image is presented as a black solid on a white or cream ground. Faces are typically featureless, though bodies, clothing, and surroundings are sometimes embellished with touches of gold, bronze, or even watercolor. Originally called “shades” or simply “profiles,” silhouettes were first seen in Europe as early as the 17th century, but were highly fashionable in America from the mid-18th through the mid-19th century. They were the snapshots of their day. They could be completed in one sitting and at significantly less cost than a formal portrait. (Advertisements from the early 1800s price silhouettes at around 10 to 20 cents apiece.) Fittingly, this art form soon took the name of an obscure mid-18th-century French finance minister, Étienne de Silhouette, known primarily for his tightfisted austerity and short tenure in that position and secondarily for his penchant for these charming pictures.

Silhouettes’ black-on-white effect was achieved in any of a number of ways, including black paint on a white ground; a black paper cutout mounted on a white paper ground; or hollow-cut white paper mounted on a black ground, revealing the image in the negative space. Silhouettes hark back to classical antiquity: They’re reminiscent of figures found on Greek and Roman pottery, architecture, and coins. And though the imagery is simple, there’s nothing clumsy or folksy about it. The figures are so solid that they feel nearly three-dimensional, and the detailed precision of the cutting and embellishment gives them an uncanny accuracy.

Artists were able to capture a near-perfect likeness of a person by shining light upon the sitter and using a

double-ended drawing device to trace his or her shadow on a wall while simultaneously copying the profile onto paper and miniaturizing it. The artist then cut the profile, whether by hand or machine. Some highly skilled artists even cut images freehand without the aid of tracing.

Silhouettes were created by professional and itinerant artists and by skilled dabblers alike. Many of the most prolific and famous silhouette artists were based in New England; still others traveled here, leaving examples of their work behind. New England silhouettists included William Chamberlain, Martha Honeywell, James Hosley Whitcomb, and Mary Pillsbury Weston, all of New Hampshire; Justin Salisbury of Vermont; William King of Salem, Massachusetts; William M. S. Doyle and Henry Williams, of Boston; Everet Howard of Maine; and Samuel Metford and Orson C. Warner of Connecticut. Because most silhouettists were self-taught in the craft, each had his or her own unique style and subtle flourishes, enabling today’s experts to identify their work.

Finding silhouettes in good condition can be a challenge; most examples have suffered some toning of the paper, but stay away from those with tears or stains. Entire collections may come up at auction, and you may also find single silhouettes in shops and online. Prices range from $200 to $2,000 apiece. Affordable 20th-century reproductions, popular during the 1950s, can offer some of the same charm as 18th-century examples. Their simple imagery and basic-black style make them a timeless American collectible.

As a fashion statement, the chic and classic all-black look has been around for a long time; it predates Coco Chanel and Johnny Cash and transcends mere clothing styles. Universal in its appeal, black has been used throughout the ages to symbolize eternity, solemnity, elegance, and formality. A light-absorbing mass, black masks imperfections and swallows details. But that weightiness is also what gives black its clarity. When used delicately, black can feel as fine and crisp as script from a fountain pen; at its most powerful, it hits us as forcefully as a blacksmith’s anvil. It is these two opposite effects that are at visual play in the fashionable all-black art form known as Early American silhouettes.

Silhouettes are miniature portraits, either busts or full figures, in which the sitter’s profile image is presented as a black solid on a white or cream ground. Faces are typically featureless, though bodies, clothing, and surroundings are sometimes embellished with touches of gold, bronze, or even watercolor. Originally called “shades” or simply “profiles,” silhouettes were first seen in Europe as early as the 17th century, but were highly fashionable in America from the mid-18th through the mid-19th century. They were the snapshots of their day. They could be completed in one sitting and at significantly less cost than a formal portrait. (Advertisements from the early 1800s price silhouettes at around 10 to 20 cents apiece.) Fittingly, this art form soon took the name of an obscure mid-18th-century French finance minister, Étienne de Silhouette, known primarily for his tightfisted austerity and short tenure in that position and secondarily for his penchant for these charming pictures.

Silhouettes’ black-on-white effect was achieved in any of a number of ways, including black paint on a white ground; a black paper cutout mounted on a white paper ground; or hollow-cut white paper mounted on a black ground, revealing the image in the negative space. Silhouettes hark back to classical antiquity: They’re reminiscent of figures found on Greek and Roman pottery, architecture, and coins. And though the imagery is simple, there’s nothing clumsy or folksy about it. The figures are so solid that they feel nearly three-dimensional, and the detailed precision of the cutting and embellishment gives them an uncanny accuracy.

Artists were able to capture a near-perfect likeness of a person by shining light upon the sitter and using a

double-ended drawing device to trace his or her shadow on a wall while simultaneously copying the profile onto paper and miniaturizing it. The artist then cut the profile, whether by hand or machine. Some highly skilled artists even cut images freehand without the aid of tracing.

Silhouettes were created by professional and itinerant artists and by skilled dabblers alike. Many of the most prolific and famous silhouette artists were based in New England; still others traveled here, leaving examples of their work behind. New England silhouettists included William Chamberlain, Martha Honeywell, James Hosley Whitcomb, and Mary Pillsbury Weston, all of New Hampshire; Justin Salisbury of Vermont; William King of Salem, Massachusetts; William M. S. Doyle and Henry Williams, of Boston; Everet Howard of Maine; and Samuel Metford and Orson C. Warner of Connecticut. Because most silhouettists were self-taught in the craft, each had his or her own unique style and subtle flourishes, enabling today’s experts to identify their work.

Finding silhouettes in good condition can be a challenge; most examples have suffered some toning of the paper, but stay away from those with tears or stains. Entire collections may come up at auction, and you may also find single silhouettes in shops and online. Prices range from $200 to $2,000 apiece. Affordable 20th-century reproductions, popular during the 1950s, can offer some of the same charm as 18th-century examples. Their simple imagery and basic-black style make them a timeless American collectible.