The Man Who Invented Nostalgia

If necessity is the mother of invention, what gives birth to reinvention? Is it dire necessity? A quest for perfection? Or a deeply personal conviction? Whatever the case, scrapping something back to its beginnings and re-creating it is a monumental task. Don’t ask me how, at the age of 43, Wallace Nutting had the energy […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanIf necessity is the mother of invention, what gives birth to reinvention? Is it dire necessity? A quest for perfection? Or a deeply personal conviction? Whatever the case, scrapping something back to its beginnings and re-creating it is a monumental task.

Don’t ask me how, at the age of 43, Wallace Nutting had the energy to do it. Not only did he reinvent himself midway through life, he also reinvented our very notions of Early American life and helped spawn American Colonial Revivalism. Then he sold that ideology to millions of middle-class Americans eager to embrace the simplicity of a bygone era.

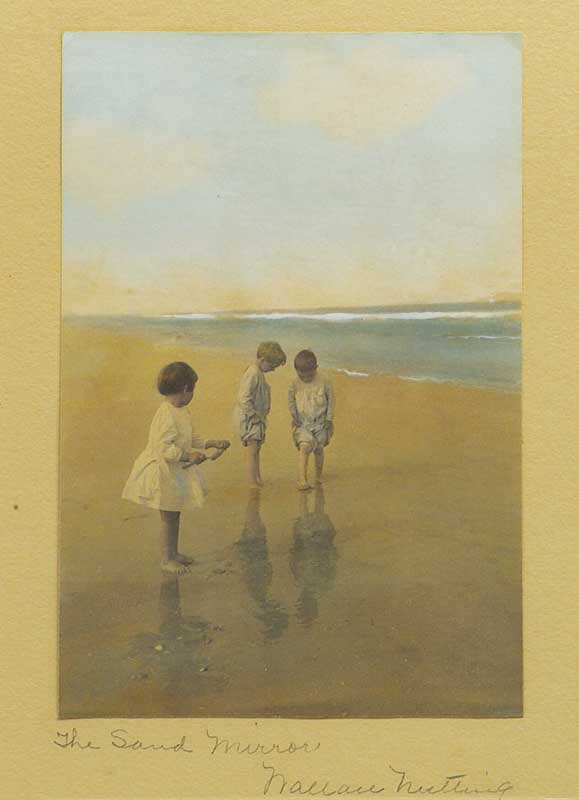

Born in Rockbottom (now Gleasondale), Massachusetts, in 1861, Wallace Nutting became a Congregational minister, serving in Providence, Rhode Island. Suffering from nervous and physical exhaustion, he reluctantly left the pulpit in 1904, a decision he called “the greatest sorrow of my life.” His doctor prescribed photography as therapy. On long bicycle rides, Nutting found his healing muse as he photographed the New England countryside. He also recognized that America’s bucolic landscape was disappearing quickly. He chose to record it on film, capturing rivers, streams, pastures, country paths, orchards, and mountains. He hand-colored the photographs, then sold them as visions of “Old America.”

Nutting opened a studio in New York and moved to Southbury, Connecticut. In 1912, with business booming, he moved again, this time to Framingham, Massachusetts. Nutting’s pictures, produced by an army of colorists who also titled and signed them, were priced from 75 cents to about $2 apiece. They sold by the millions and were found in homes throughout New England and across the country. My own working-class grandmother had a Nutting photo of a cherry tree in full bloom hanging in her living room.

As Americans’ interest in “Old America” grew, so did Nutting’s evangelizing on the subject. He embarked on a series of photographs depicting interior scenes of an idealized Colonial existence: evenings by the fire, a ladies’ sewing circle, a mother rocking her child to sleep. These quaint images, suggesting a time when home, family, and simple pleasures were at the center of American life, were highly sentimental and likely far from reality. Nevertheless, they struck a chord with the middle class. Sure, they were a bit of a fib–a reinvention of sorts–but they got Americans energized about their nation’s past.

Continuing in his crusade, Nutting wrote books and countless articles on American antiques. Fueled by the success of his picture enterprise, he then began designing some of the finest-quality reproductions of Early American furniture ever made; his craftsmen used traditional woodworking techniques to create these pieces. The venture never made a profit, but it became Nutting’s personal calling. From his new pulpit, he spoke to a flock of homemakers, designers, antiquarian scholars, historians, furniture makers, and collectors, all eager for advice and a taste of his knowledge. By the 1930s, interest in Colonial Revivalism had waned, but when Nutting died in 1941, he nevertheless reigned supreme as the definitive tastemaker of the early 20th century.

Nutting’s work still resonates today. His pictures, once so affordable, are now the Holy Grail of hand-tinted photography, selling for a few hundred to several thousand dollars at auction. His reproduction furniture fetches five figures and graces the galleries of several museums.

Let’s face it: Reinventing anything, much less oneself, is difficult work. Perhaps Wallace Nutting found it too difficult to do on his own; he needed all of America along for the ride.

Catherine Riedel represents Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers of Boston and Marlborough, Massachusetts. 617-350-5400, 508-970-3000; skinnerinc.com