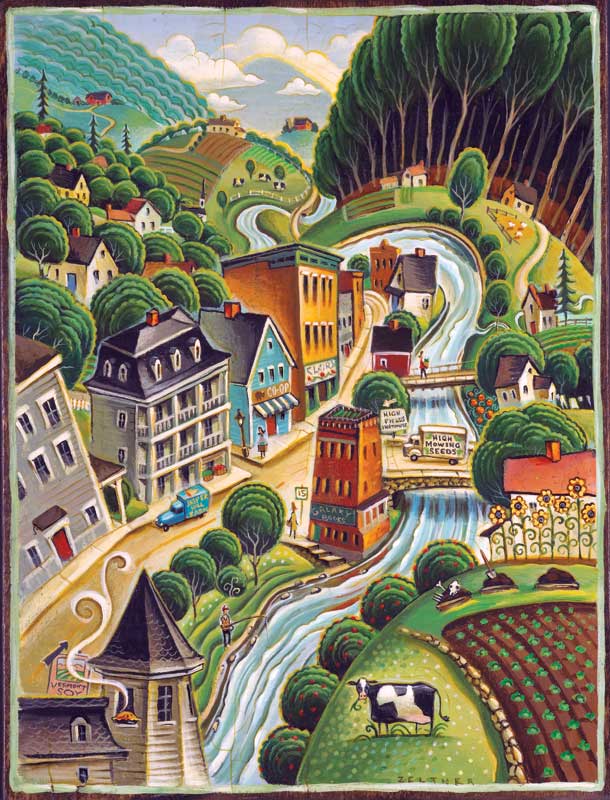

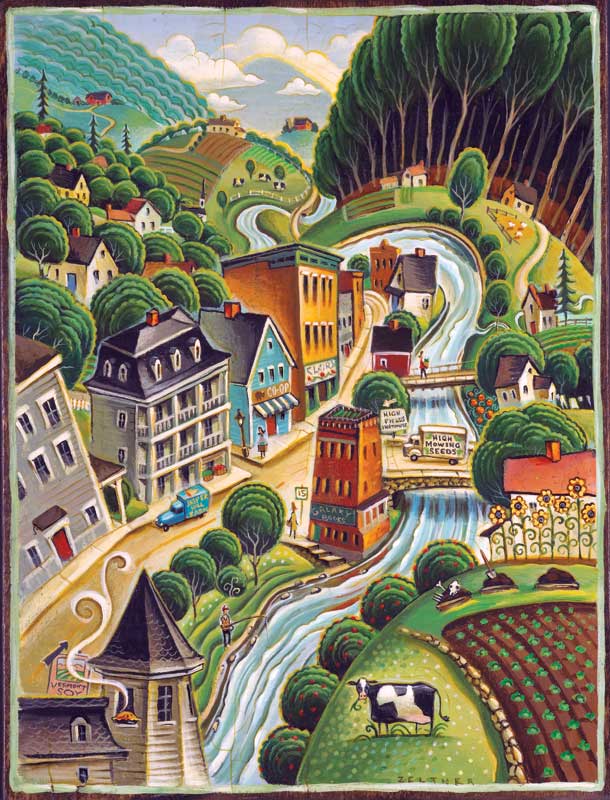

Hardwick, Vermont, and the New Frontier of Food | How New England Can Save the World

How New England Can Save the World, Part III in a series Part I: The Maine Way: Aroostook County Part II: Vermont Neighbors Part IIII: A Bang for Your Buck in the Berkshires When you think of Vermont–white church on the tidy green–you’re not actually thinking of Hardwick, which in its days as the “Building […]

Photo Credit : Zeltner, Tim

When you think of Vermont–white church on the tidy green–you’re not actually thinking of Hardwick, which in its days as the “Building Granite Center of the World” used to boast a dirty-movie theater and a lot of bars. And those were the good times. In November 2005 an enormous fire wrecked the historic Bemis Block in the middle of town. (It has since been reconstructed.)

Likewise, when you think of “compost,” you may imagine a healthy-looking gardener spreading the loamy remains of his erstwhile vegetable soup on the raised beds where he’ll grow next year’s carrots. That’s not Tom Gilbert.

He’s healthy-looking enough, but he’s standing in a dusty parking lot high on West Hill Road, overlooking town. “You’re surrounded now by three decomposing carcasses,” he says, pointing proudly to a trio of brown mounds. Tom Gilbert runs the Highfields Center for Composting, which introduced “livestock mortality composting” to Vermont. On a dairy farm, 5 percent of the herd is likely to die each year, so knowing what to do with the remains is important.

“You don’t want to just haul it out to the field,” Gilbert explains. “That’s a lot of blood and bone that will go to waste,” when it could be improving the soil. So here’s one recipe: an 18-inch base of woodchips, a 6-inch layer of sawdust, a thin layer of fresh corn silage (or haylage, or horse manure), the animal, and then a cap of silage–24 inches of material on all sides of the carcass. Done correctly, with proper siting (away from surface and ground water) and air flow, the process inactivates pathogens and produces a rich compost.

“There’s a full-grown Holstein in there–I put him in two weeks ago,” says Gilbert, who sticks a 2-foot-long thermometer into the pile. “One hundred forty-five degrees. If you go in with a shovel, you’ll find nice clean bone. We’ll leave it a while, and the skull and the pelvis will still be there, but now they’ll be brittle enough that you’re not going to pop a tire if you drive the tractor over it.”

Gilbert composts more than cows; in fact, he’s pioneered a rural composting system that gathers up much of the food waste from the surrounding area, including schools, farms, and restaurants. The collection truck drives a 76-mile route; some of the stops are 15 miles apart, which reduces the economies of scale. Even so, once the workers have the garbage up on the piles, where they can roll it with a backhoe every few days, it doesn’t take long before it turns into fertilizer. “If you assume that every cubic yard of compost offsets an equivalent amount of synthetic nitrogen (chemical fertilizer), and accounting for mitigated landfill emissions,” Gilbert calculates, “our little operation here is offsetting greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to not burning some 26,000 gallons of gasoline a year.”

If you want to change the world, or even a corner of it, compost helps a lot. If Vermont as a whole recycled all of its food waste, it could compost 20,000 acres of vegetable fields. Together with good cover crop practices, that could be enough to grow most of the produce its citizens consume. And Vermont is a little place. Imagine New York City composting; it’s comparatively easy to collect food waste when there are more households in Manhattan alone than individuals in all of Vermont. The resulting fertilizer would be enough to make New Jersey the Garden State once more. “Soil is the frontier of where we need to be going,” Gilbert declares.

But forget New York–Hardwick is interesting enough on its own. And compost is just, literally, the beginning. Almost everything here is conspiring to produce a produce renaissance, a (soy) milky way toward the future. In fact, it may be the single most interesting agricultural experiment on the continent. In a lovely new book, The Town That Food Saved, journalist Ben Hewitt declares that its residents “are more able to sustain themselves on food grown by their neighbors than perhaps any other community in the U.S.” To understand why, follow the local food chain.

Some of Tom Gilbert’s compost gets trucked about a mile down the road to Wolcott, to the gardens where High Mowing Organic Seeds grows its product. High Mowing is one of the country’s biggest organic seed companies, which means it isn’t all that big–a couple of million dollars a year in revenue. But it sure is beautiful.

“People say it’s hard to grow organic broccoli and cauliflower,” says Tom Stearns, the ebullient proprietor. “We try to find the ones that really crank–like these,” he says, pointing to specimens approximately the size of beach balls. “Organics need to be really vigorous to out-compete weeds. And they tend to need more root hairs, because their fertility is widely distributed instead of being intravenously injected. These guys here are perfect if you like radishes; I don’t much like radishes. This is spicy ‘Golden Frill’ mustard greens, a new variety we added in 2009. Here’s an Asian green, hon tsai tai–just eat, eat. We have two fields up here, and we keep them a mile apart to prevent crossing. We have zucchini in one and pumpkins in the other. Or else you get pumpkinis. Or maybe zuckins.”

The High Mowing warehouse is down the hill–metal shelves are filled with the beginnings of a million meals. Quinoa … spelt … a big bag of ‘Tom Thumb’ popcorn … Italian flat-leaf parsley. But not just flat-leaf: double-curl, triple-curl. Two young women are hunched over a cutting board, examining onions. “We have a new favorite,” one reports. ” ‘Rossa di Milano.’ It really stood out. It beat ‘Red Baron.’ High, blocky shoulders.”

Stearns is gushing on about his business–the fast growth, the network of small growers, the sterling germination rates–but I’m dizzy from the sheer fertility. “That bag over there has 30 pounds of cuke seed,” he says. “That’s 60 acres.” Orders come in by the hour: “People who used to get five or ten packets are suddenly getting 20 or 30. The 10-by-10 garden is becoming 20-by-30. People are trying to put food up. I love high oil prices.”

Lots of Stearns’s seed goes a few miles north, to Craftsbury, where Pete Johnson of Pete’s Greens has been pioneering year-round organic farming in northern New England. Johnson built a solar greenhouse as his senior project at Middlebury College, and then started thinking bigger. By now he’s figured out how to move his greenhouses on tracks, so that he can cover and uncover different fields, and as a result grow greens 12 months of the year without any extra heat. And that lets him run his CSA (community-supported agriculture) operation, dubbed “Good Eats,” year-round.

Say your family wants the spring share. You’d pay $748 for a weekly basket from February to June; in mid-April–a tough time of year for local farming–you’d be getting maybe a half-pound of mesclun, a bunch of parsley and some scallions, three pounds of carrots, some early radishes, two pounds of beets, two pounds of fingerling potatoes, a half-pound of oyster mushrooms, a loaf of local bread, a half-gallon of local cider, and a half-pound of local feta cheese. You can add a meat share if you like ($199 for monthly delivery): a five-pound chicken, some pasture-raised hamburger, a couple of locally farmed trout, and a pound of bacon cured without nitrates. By Johnson’s calculation, it all comes to 20 percent less than buying the same stuff at a supermarket.

But we’re used to thinking of local food as more expensive. “Compared with what?” Johnson asks, when a reporter from The Christian Science Monitor raises the price question. “Compared with the absolute junkiest food you can buy in a supermarket? It’s too bad we think we can’t afford the most important thing in the world, when we’re so wealthy.”

Other seed from High Mowing is dispatched a couple of miles in the other direction, to the headquarters of Vermont Soy, in Hardwick. They hand it out to four or five Vermont farmers, who in turn produce the beans that become tofu and soy milk in the small factory here. (Only half the space is used for tofu; the other half somehow turns cow’s-milk whey into varnish for furniture.) The owner, Andrew Meyer, grew up on a local dairy farm, the kind of farm that’s been going under for decades as the milk industry turns into a commodity business dominated by huge Western dairies. So he understands the need for a more regional food economy. “I think Vermont hasn’t even tapped its capacity for growing food,” Meyer says. “Someday the train will come back, and we’ll be sending a refrigerated car once a week right to Chelsea Market. We’ve got two of the biggest markets in the world right nearby: Boston and New York.”

But for now, forget about Boston and New York. A fair amount of the food from Hardwick is going to … downtown Hardwick. To, for instance, a lovely new restaurant, Claire’s, which in its first year of operation won a spot on Condé Nast Traveler’s “Hot Tables” list. Fifty local investors put up a thousand bucks apiece to help get it started, and they’re taking their money back out in the form of dinners.

And what dinners they are: Some weeks, local garlic, tomatoes, eggplant, and basil might combine for a Northeast Kingdom ratatouille; other nights an area apiary might pour its newest mead. Linda Ramsdell, a partner in Claire’s and owner of the uniquely delightful Galaxy Bookshop across the street, often brings in cookbook authors for special dine-and-read evenings; needless to say, the regular live music is as local as the food.

And, needless to say, the evening often ends with a plate of cheese. One of the real foodie highlights of the Hardwick area is the newly opened cheese cave in Greensboro, where many of Vermont’s best-loved artisanal products spend their final few months aging in the climate-controlled rooms.

Proprietors Andy and Mateo Kehler were already making award-winning cheeses at their Jasper Hill Farm, but they knew that many of their small-scale colleagues around the region had trouble storing and shipping their products. So when they were building a facility for their own stuff, they just kept building; it’s now 22,000 square feet, with seven underground vaults: different climates for everything from blues to clothbound cheddars. It can store 2 million pounds at a time, from 39 degrees to 55 degrees; it’s a pungent paradise.

But it’s also part of an economy. It’s a way to take fluid milk, which is currently a drag on the market–selling for less than it costs to produce–and turning it into something that goes for $20 a pound. That means jobs, and everyone on the Hardwick food scene is at least as serious about jobs as they are about flavor. This year, the Vermont Food Venture Center is moving into Hardwick’s industrial park. It’s a place where new “agrepreneurs,” to use a term coined by Ben Hewitt, can figure out how to make that new cheese, that new salsa, that new tempeh, all on a scale that will also let them make money.

“We need businesses that can feed off each other,” says Andrew Meyer. “The waste stream of one would be the feedstock of the next.” And all of it would provide real resilience for a rural economy that would like to depend neither on the boom-and-bust of quarrying nor on the quaint unreality of providing scenic vistas for summer homes.

Over lunch at the headquarters of The Center for an Agricultural Economy, which sits next to Claire’s and serves as the organizing hub for this food experiment, Tom Stearns points out that he’s had 40 job applications in the past week at his seed farm. No wonder: Some of the slots pay $40,000 a year, they come with benefits, and there’s all the produce you can carry away from the test gardens. “We still have to convince the local kids, though,” he says. “They’ve all grown up believing that there’s no future in farming. But now there is.”

To read more about Hardwick, we recommend Yankee contributor Ben Hewitt’s new book, The Town That Food Saved: How One Community Found Vitality in Local Food (Rodale, 2010).