Remembering Stephen Huneck | The Artist Behind Dog Mountain

When artist Stephen Huneck died in 2010, he left behind his beautiful Dog Mountain park and chapel, his whimsical dog art and books, and so many questions.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

The gallery at Catamount Arts seems hardly large enough to fit it all: handcrafted furniture, sculptures, woodcut prints. In his 25 years as a carver, Stephen Huneck produced enough wood shavings to fill a room this size, but it will have to do. This retrospective is not just an opportunity to view Huneck’s lifework; it’s also one last chance for the town of St. Johnsbury, Vermont, to say goodbye.

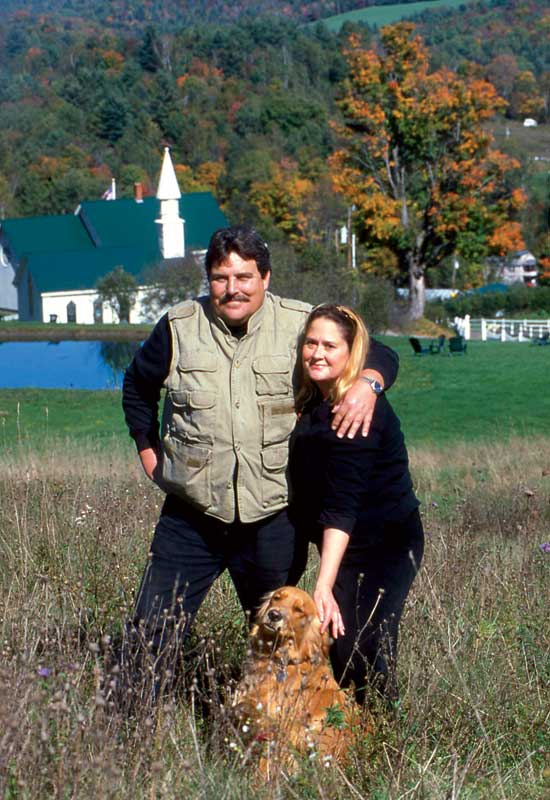

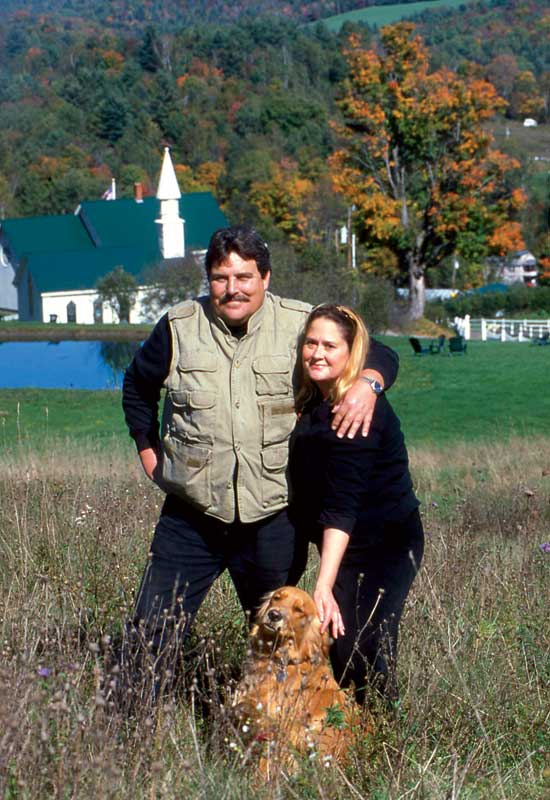

Stephen Huneck died in his car on January 7, 2010. The news couldn’t have been more shocking. In the art world, Huneck had made a name for himself as an upbeat artist with a whimsical style. In public, he was known as a jovial bear of a man with a personality as large as his overgrown mustache. To everyone, he was someone you wanted around when you needed a laugh. But in a flash on a cold winter morning, he was gone, and no one understood why. Every death leaves questions, some more than others.

On the edge of Faulkner Park in Woodstock, Vermont, there’s a house with a very odd weathervane. Instead of a thoroughbred or a rooster, Jim Bryant’s cupola is topped with a dog angel. “People will walk by and look up and recognize that it’s a Lab with wings, and they start laughing,” Jim chuckles. “Every time that happens, it’s another reminder of Stephen.”

Jim first met Stephen Huneck about 15 years ago, after frequent trips to Huneck’s gallery in Woodstock. “No one would leave the gallery without a big smile on their face,” Jim recalls. He remembers bringing his sister there for the first time: “Within minutes she was roaring with laughter. There was a piece of furniture; it was a life-size nun. To open the cabinet, you had to …” Jim trails off, laughing. “You had to put your hands on the nun’s chest!”

Stephen, raised in Sudbury, Massachusetts, began sculpting wood in the mid-1980s, and his puckish sense of humor quickly distinguished him from his contemporaries. “The art at that time was very angst-driven; very political and negative and dark,” recalls Gwen Huneck, Stephen’s wife and his companion since 1975. Stephen focused instead on subjects that made him happy, and more than anything he found joy in dogs. He’s probably best remembered for his series of woodcut prints featuring dogs in humorous situations, with pithy captions. One depicts a dog sniffing under another’s tail, with the caption “Greetings.” Another shows a dog surrounded by its family and reads, “Dogs make people human.”

Many of his prints featured the same dog, a black Lab in a red collar. She was modeled after Stephen’s own dog, Sally, and Stephen would go on to write a series of children’s books based on her adventures. His second book, Sally Goes to the Beach, was a New York Times best-seller. With his simple, upbeat message, Stephen quickly found an audience with both children and adults. “Who’s against nature and love and dogs?” Gwen asks. “Well, a couple people, but not many.”

As Stephen’s success grew, he and Gwen made a home for themselves in St. Johnsbury. They fixed up an old post-and-beam house, injecting Stephen’s imagination into every detail. The banister is a wiener dog, the bathroom faucet a bronze Labrador (pull the tail down for water). Stephen hand-carved most of the furniture and spent a summer inscribing bright, joyful sunflowers into the kitchen cabinets. He built an expansive studio where he’d go early every morning, still half-dreaming, and start on his next creation. A print above his worktable riffs on his “Greetings” piece with an image of himself sniffing under a dog’s tail, with the caption, “Dog Fanatic.” “We didn’t sell many of those,” Gwen jokes.

A mile down the road from his home, Stephen created his masterpiece: a 150-acre dog park, free and open to the public, with trails, forests, and a swimming pond. He dubbed it “Dog Mountain.” At the center of it he erected a classic Vermont chapel dedicated to the memories of lost pets. “Stephen wanted a place where people could find closure,” Gwen explains. “He also wanted to create the perfect spot to bond and have fun with your dog while your dog’s alive.” It’s become a pilgrimage site for dog lovers, drawing visitors from around the world.

Photo Credit : Proulx - Submitted by Dan

Despite Stephen’s success, the recession took its toll on his business. Usually jovial in public, Stephen began showing signs of strain. Just before Christmas 2009, Gwen and Stephen had lunch with Jim and his family. Jim noticed Stephen’s hands shaking and asked about it. “I have to get through this winter,” Stephen replied. “I just have to get through this winter.”

Then in January, Gwen got a call from Stephen’s psychiatrist, saying that he’d never arrived for his appointment. She went looking for him and found his car parked in front of his doctor’s office. From a distance it looked as though he were sitting in the front seat reading the newspaper, but as she approached the car, the truth became clear. Stephen had shot himself. “I think he was trying to spare me that,” Gwen recalls. “It ended up I was the one to discover him, but I think he was trying to spare me that experience.”

The interior of the Dog Chapel glows in the late afternoon. The sunlight catches in a row of stained-glass windows that celebrate the qualities of canine companionship: loyalty, play, trust. On every inch of wall there are remembrances, two or three layers deep in places: pictures of lost pets, with notes–some heartbreakingly raw and sincere–trying to put into words the complex bond of love and friendship we feel when we say, “Good dog.” It’s a peaceful, disarming space. Of all the small tragedies that befall mankind, the loss of a pet may be the most universal. It’s a pain that binds us together, and here in this chapel Stephen created a safe place to heal.

Gwen sits in one of the five small pews. Her own dogs–Molly, Daisy, and the current incarnation of Sally, the third one and the first male (his full name is “Salvador Doggie”)–mill about the chapel. Occasionally one of them nudges at Gwen’s hand for a scratch.

“I was surprised after he committed suicide when I talked to some people and they were totally shocked,” she says. “People who knew him very well, I thought. He just never shared that with anybody.”

Stephen Huneck had suffered from depression most of his life, although he’d grown adept at hiding it. Behind his jovial exterior was a man who could grow despondent at times, Gwen says. Like many artists, he had trouble internalizing the praise he received for his work, she feels, and he harbored a low self-image.

Gwen thinks it’s possible that some people just saw what they wanted to see in Stephen: a self-made man living his dream in the beautiful Vermont countryside. “People would say to us, ‘You’re so lucky. You have the perfect life,'” Gwen recalls. “And we were thinking, Are we going to make payroll this week?“

Certainly Stephen’s art didn’t provide any clues to his depression. Gwen jokes that maybe if he’d painted morbid things, people wouldn’t have been so surprised. Even through tears, she finds her laugh easily. Gwen has small, bright eyes and round cheeks that dominate her face when she smiles. Sadness doesn’t suit her, and it’s easy to see what she and Stephen saw in each other.

As the recession grew worse, Stephen began working less. He would close himself into the media room and watch cable news obsessively. “It was probably a bad business move, but we tried to keep people on as long as we could,” Gwen says. “It just sucked all the money, basically. And then we came to a point where we couldn’t anymore, and that was the breaking point for him.” On January 5th, they let go 10 of their 12 employees at the workshop and gallery on Dog Mountain, many of whom they’d known for years. They thought of them as family, and Stephen felt personally responsible. “He was all alone,” Gwen says, “watching CNN in the morning and thinking he was a failure.”

Later that day, Stephen talked to Gwen about suicide. “He said, ‘It will be better off without me,’ and he meant financially,” Gwen recalls. “I pooh-poohed that. I said, ‘That’s not true. Don’t even think that.'” Gwen’s voice fails her for a moment, and she wipes the tears from her eyes. “What he said to me basically was ‘I’ll talk to my psychiatrist on Thursday,’ which was two days away. I realize now he’d already made up his mind about what he was going to do.”

In the wake of Stephen’s suicide, Gwen had no idea what would happen next. But as news of his death spread, Web orders came pouring in from around the world. Longtime admirers and speculators scrambled to buy up his art. It saved the business, leaving Gwen to deal with a bittersweet reality. “Even though it was very sad and it didn’t make up for it, he was right in that it did help me,” she says.

Gwen cries now, her voice resonating off the chapel’s high ceiling: “You know, that’s why I’m still here. It’s not what I would have wanted to happen, but it allows me to …” Her voice trails off for a second. Then, resolutely, with only a slight tremor in her speech, she says, “I don’t feel any anger. I just feel love, and I feel sadness that he took that choice. But I think he did it out of love, really. Rather than see us lose our home or lose Dog Mountain, he did the only thing he could think of that might save it.”

In every suicide, no matter the circumstances, that person takes with him a whole universe of possible futures that include him. When survivors look to tomorrow, all they can do is choose the best of what’s left. Gwen would have gladly lost everything if it meant keeping her husband, but she didn’t get to make that choice. When Stephen died, he left her with a beautiful chapel on a beautiful mountain and the horrible question of what to do next.

On a sunny day in May 2010, a herd of dogs bound off a shuttle bus at the foot of Dog Mountain, their owners following behind them. It was important to Gwen that Stephen’s memorial service be pet-friendly.

It’s an informal affair. A hundred or so people sit in chairs set up by the dog pond. One by one, they get up to share their memories. Some knew Stephen for his art and others through his advocacy for dogs. Some are old friends, and a few are complete strangers who were inspired by his life. It’s a mixture of tears and laughter. Seemingly every time things get too heavy, the speaker is interrupted by the splash of another dog flinging itself into the pond. Everyone agrees that Stephen would have wanted it this way.

The group reconvenes at an overlook at the top of Dog Mountain for a final goodbye. They gather around a statue of a dog angel Stephen erected there years ago. A local minister begins reading from Stephen’s final children’s book, which he’d written just weeks before his death. It’s called Sally Goes to Heaven.

At the beginning of the story, Sally wakes up in heaven and is surprised that she’s no longer in pain. “‘She never felt so good,'” the minister reads. “‘The next thing Sally notices is a window. It was all that she could have hoped for. It was a window into her old house through which she could look anytime.'” He chokes up, and Gwen comes out of the crowd and gives him a hug. “‘Looking through the window,'” he continues, “‘Sally sees that everyone is crying. Sally starts to cry too. Sally’s tears are for her family. She wishes she could comfort them and explain to them about her pain being all gone. Sally is not too sad because she knows that they will all be together again in Heaven one day.'”

No one would have faulted Gwen if she’d decided to close Dog Mountain–if she’d found it just too sad to be around. But Gwen says the thought never crossed her mind. Dog Mountain was too important. “I think what Stephen did was really, really profound,” Gwen says. “It’s more than just nice art. It affected people. He intentionally tried to put healing energy into things. That’s what he wanted to give people.”

Stephen Huneck dealt with his depression by trying to make it into something positive. His art transformed his demons into laughter. And even if that wasn’t enough for him–even if his life ended in sadness–it doesn’t cheapen the gift he gave to other people or the gifts he gave to Gwen.

People still visit the chapel on a nearly daily basis. The walls are so thick with remembrances now that Gwen is concerned about where they’ll be able to fit new ones. “Maybe the ceiling,” she quips.

She’s left the chapel untouched since Stephen’s death, save for one addition: On one wall of the foyer she’s cleared a space for him. A handful of photos from their life together are wedged between those of the Dobermans and Labradors of strangers. It’s a slight aberration from Stephen’s original vision, but one that Gwen feels he would have approved of.

Gwen doesn’t see any of this as an ending. As she chooses the art for Stephen’s upcoming retrospective in St. Johnsbury this summer, she doesn’t approach it as a final viewing, but as the continuation of her husband’s legacy. “It gives me purpose in life,” she says. “It helps me feel connected to Stephen. I’m like the caretaker of it now.”

Gwen hopes Dog Mountain will always remain open, although she doesn’t know who will maintain it after she’s gone; she and Stephen had no children. With a wry smile at her black Lab, she ruffles his ears and says to him in an excited voice, “Maybe we’ll leave it to Sally.” Stephen would have laughed.

Chapel and gallery are located at 143 Parks Road, St. Johnsbury, VT. 800-449-2580; dogmt.com