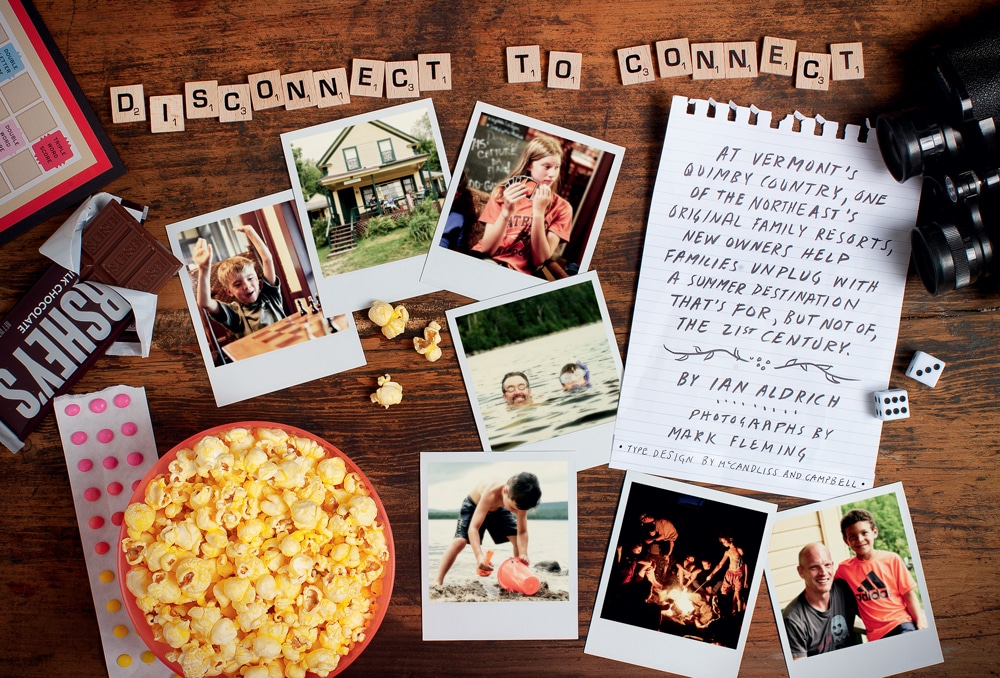

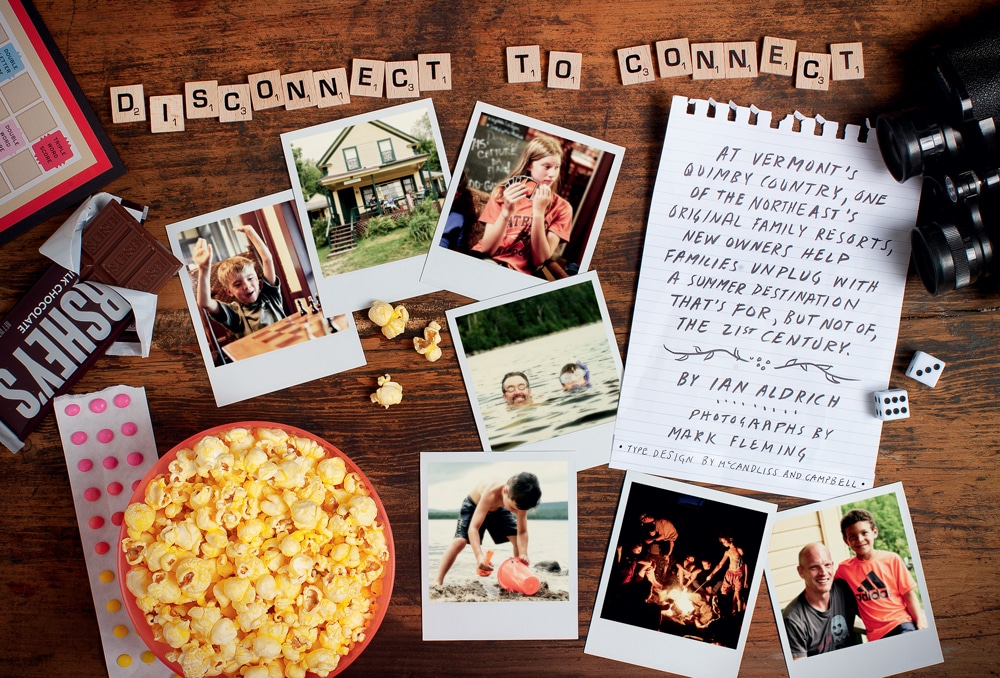

Quimby Country | Disconnect to Connect at This Vermont Family Resort

At Vermont’s Quimby Country, one of the Northeast’s original family resorts, new owners help families unplug with a summer destination that’s for, but not of, the 21st century.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming | Type Design by McCandliss & Campbell

It was in the middle of Big Averill Lake, a cold, clean body of water located in the eastern tip of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, that my 7-year-old son, Calvin, began lamenting our departure. We’d idled away the past five days amid exquisite summertime weather at Quimby Country, a family resort in the tiny town of Averill (population 24). We’d hiked, paddled, ridden our bikes, played tennis, battled at Ping-Pong, sat by campfires, and even managed to win at bingo.

Calvin had made friends with a couple of other boys his age, and together they roamed around with a casual freedom that seemed lifted from some kind of idealized version of a child’s summer. They’d hunted for crayfish, gorged on s’mores, navigated shoreline rocks under an evening sky, and slept out under the stars. There had been impromptu soccer games, archery lessons, and bike races.

“I wish we didn’t have to leave,” Calvin said, dipping a hand in the water.

I wasn’t sure how to respond, because frankly, I didn’t want to either.

_

Even by northeast kingdom standards, Quimby is remote. Averill, after all, is not a place you stumble upon. Up and up you go, past St. Johnsbury and Burke, practically scraping the Canadian border, before you arrive. Quimby land extends more than 1,000 acres and includes two lakes. It practically is Averill.

In addition to all those woods and waters, Quimby Country includes a lodge, a clubhouse, and 19 lakefront cottages. You’re in the backwoods but in cottages with kitchens, full baths, and wood stoves. They extend like a ribbon from the main building, where guests gather for three big meals a day and a lot of porch-time reading in between. Staffers serve the meals; cleaning crews turn over the cottages each morning. Everything’s rustic but not uncomfortable—and at times it can even feel a little sophisticated.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

It’s like one-stop vacationing. There are bikes and boats to use, counselor-led biking and fishing sessions for kids, and evening games for everyone. I fired up my car only once, and that was because I’d forgotten to bring enough saline solution for my contacts. In some ways, the rhythm of our days was not that different from that of guests who had been coming here for generations.

The story of Quimby Country begins in 1893, when Charles Quimby, a local hardware store owner, took on half-ownership of the property in lieu of payment for the materials used to build it. Cold Spring House, as it was then known, catered to anglers and hunters from around New England, the earliest of whom slept in platform tents. Just getting there was an ordeal: a long train ride, then a horse-and-buggy escort. The journey’s length no doubt explains why visitors often stayed a month or two.

In 1904, Charles Quimby bought out his partner, built the first nine cottages, and changed the name to Cold Spring Camp. But the big change came when Quimby’s 29-year-old daughter, Hortense, inherited the property 15 years later and set forth a vision for the place that far exceeded anything her father ever imagined. Hortense transformed the camp from a retreat for men who wanted a respite from indoor life into a new kind of vacation for a growing class of Americans with more leisure time. She built more cottages, added horse stables, constructed a clay tennis court, and hired staff to manage children’s activities. For weary city folks who wanted a shot of true Vermont, there was no better place. Over the next half-century, Hortense was the face of what became known as Quimby Country. She was a forceful, confident woman who knew how to push her ideas through even when others weren’t ready to accept them. She was a conservationist long before that ethos was in vogue, and a successful businesswoman at a time when there was little tolerance for that kind of thing.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

“She built the place up all alone … without the help or encouragement of anyone,” wrote Robert Pike in his 1959 classic, Spiked Boots, which chronicled life in the North Woods. “It must have near broke her heart more than once, but the tougher the sledding, the harder she pulled. She never quit.”

The loyalty she inspired was evidenced by what came next. When illness and age prevented Hortense from managing the camp any longer, she sold it in 1965 to a group of longtime guests. Over the next 50 years, they both expanded and adhered to her original vision.

In early 2018 the camp again came under new ownership, as Lilly and Gene Devlin, two Vermonters with a background running wilderness and school programs, took over. In this age of hyperconnectivity, the Devlins, who are in their mid-40s and the parents of three teenage boys, are attempting something ambitious: to build an experience that’s for, but not of, the 21st century. There’s no cell service, and while Wi-Fi exists here, the Devlins make it available only briefly in the mornings and evenings.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The effect is vacation time that allows for more serendipity. Oh sure, there are structured activities—canoe trips on the Connecticut River, hikes up nearby Brousseau Mountain, archery lessons, baking classes for kids, Friday massages for the parents—but there are also wide-open stretches of the day to explore, to play. I saw a 12-year-old girl sitting quietly on a rock by the water, writing in her journal. Later, a jolt of excitement ran through the camp after a teenage boy helped a counselor rescue a lost loon and return it to the lake. Calvin and his buddies organized their own tennis matches, bike races, and soccer games. They built a fort. They kayaked. They swam. Just a little bit of time away from a screen created a surprising distance from any kind of digital connection. Not once did he ask if he could watch something.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The Devlins know that gone are the days when families had the time and resources to block out weeks of vacation—work is always calling, kids’ sports schedules can be all-consuming. But they believe that even a short break from some of these pressures can make a big difference not just in what parents and kids do together, but also in how they relate to one another.

“We want this to be a place where families can take a real vacation,” Gene told me, “where they can truly spend time with one another in a way they can’t in the rest of their life.” He gestured toward some parents who were trading turns at the new archery area while their children waited to go next. “This is what we want. People getting out of their confined roles. Kids doing something new because they see their parents doing something new.”

_

It was midafternoon on a Saturday in late July when Calvin and I arrived at Quimby Country. Inside the main lodge, a few other guests were already checking in. “We should just be parents by committee,” joked one mother to another. “I’ll take them for 12 hours and then you do the same.”

Around us were all the hallmarks of a world that had not changed much since Hortense Quimby’s time. A large fieldstone fireplace anchored a seating area; just beyond was a sprawling dining area flush with natural light. In a part of the building that served as a sort of headquarters, a bookshelf was lined with photo albums that went back to Quimby’s earliest years. On a back wall were wooden mail slots for each of the cabins, all named after Hortense’s favorite fly-fishing ties: Ginger Quill, Silver Doctor, Parmachenee, Brown Hackle. An old chest freezer filled with cold drinks and candy hummed. Guests were instructed to write down their purchases in a credit log, which was tucked into a weathered leather-bound book. As I registered with Lilly Devlin, Gene showed my son the cooler. Calvin looked over at me in bewildered amazement. All of this? Anytime I want? he seemed to ask. Within a couple of days he and his new crew of friends would make a freezer stop a regular part of their midafternoon itinerary.

We soon found our days stocked with such gentle familiarities. Easy routines filled our easy days: runs and bike rides and reading on the front porch. On Sunday evening the Devlins hosted the camp’s customary welcome cocktail hour. On Wednesday there was the annual Quimbledon tennis tournament; those who didn’t play sat on a lawn bank to cheer on the action. Families competed in a high-stakes Olympics (archery! slingshots! scavenger hunts!) on the final full day, then gathered around a large lobster bake.

As it was for other parents and kids, entire chunks of the day would pass before I’d see Calvin again. He’d be under the watchful eye of another adult as he splashed around in the lake, or sitting in the shade with a fellow guest who showed him how his drone worked. It’s probably the closest I’ve comfortably and willingly come to communal living.

Many of the families we met had ties that went back decades—generations, even—and often chose the same weeks each summer so they could join their Quimby friends. One guest told me she’d never been to her young grandson’s birthday because it always fell on her Quimby week. “He lives only a mile from us, so we do see him—but I’m still not sure my daughter understands it,” she said.

The pull was the same for others. There were the Martins, Ginny and her husband, Dick, a retired AT&T executive, who live in New Jersey. They’d started coming in the early 1980s, when their kids were young. Now those children were grown with kids of their own, and they were all here together. The same was true for Chris Dotterer and Richard Butcher, a pair of Pennsylvania physicians who were visiting with their two adult sons. Richard, who’s 71, experienced his first Quimby summer when he was 10.

“This is where my dad and I took up fishing,” he told me. “I’d buy him lures, and this is where we’d use them. My dad was pretty shy, but up here he had more friends and was more outgoing. I saw a different side of him.”

Not far from Richard and Chris’s cabin were the Patakis, who had taken over several cottages. Lou and Jane of New York City had committed to nearly three weeks at Quimby for what basically amounted to a rolling family reunion. It was their summer center point, a legacy that had begun in the early 1950s when Jane was a young girl. She introduced Lou, an astronomy professor at New York University, to the camp in 1966, after they married. Both their kids, Jon and Daisy, eventually worked as camp counselors. Now, with two sets of children of their own, Jon’s and Daisy’s families were here, too, with Daisy traveling all the way from London to keep her tradition going. Altogether, there were 17 Patakis vacationing with us.

“I came up here with a couple of things to do,” Lou told me as we sat out on the lodge porch during the Sunday evening cocktail. He shook his head and took a sip from his drink. “I did one of them and then said to hell with the rest. It can wait until I’m back home.”

_

A confession: I’d arrived at Quimby with a skeptical eye. I enjoy staying connected (and being on my phone) far more than I like to admit. What if I missed a headline, a tweet, a text, or an email? And just how were Calvin and I going to fill our days?

But then something kind of marvelous happened: I made do just fine without my phone for much of the day. The world marched on without me. I also learned a few things, such as: My son is probably going to beat me in Ping-Pong in a couple of years, but it’s going to be a little longer before he takes me in tennis. Other things: He really likes building forts, tag is an endless obsession of his, and an expensive mountain bike is most likely in his future. Gene was right. At Quimby, I saw Calvin—and my relationship with him—in a completely different way.

There was something else, too. Calvin was absolutely enchanted with the freedom he had. He roamed with total confidence, blazing down the camp roads on his bike, securing his own breakfast while I went for a run, formulating his own games and schedule without some micromanaging adult to mess up his plans. He owned his days, and he couldn’t get enough of it. After we returned home, Quimby was the very first thing he talked about when he was asked about his summer.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

It continued for months afterward. Over breakfast last December I asked Calvin what he wanted to do most in the new year. He thought about it for a moment. “I really want to go back to Hawaii,” he finally answered, recalling a memorable family trip we’d taken a few years before. Then he paused again. “Actually, Quimby Country,” he said. “That’s where I want to go. Not Hawaii.”

I couldn’t really argue with him. We plan to return this July.

My Mom as a teenager worked as a nanny to three little boys one summer for Miss Quimby. My husband and I spent 4 days one spring on a birding trip there with Bryan Pfeifer, had a cabin to ourselves, tended the wood stove and had a wonderful time viewing all the warblers, lady slippers and lake amenities that Quimby’s had to offer, to say nothing of the delicious meals and friendly staff. Would love to do it all again!!!

Hello Diana, thanks for your comment. What a wonderful reflection. We would love to welcome you back. In fact, we are trying to get Bryan Pfeifer back for a visit to offer our guest a very similar experience to the one you had. We’re glad you have so many fond memories of Quimby Country!