The Mysterious Siren Call of Appledore Island

Celia Thaxter found peace and rare beauty on a barren island eight miles out to sea. Visitors keep arriving to see it for themselves.

Her reconstructed garden today.

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

People fall in love with Appledore Island without knowing why or how. It’s little more than a granite mound rising out of the ocean. There are no sandy beaches here, just seaweed-strewn boulders ringing the shoreline. In summer, the sun is merciless. In winter, icy winds rake the island continuously. It’s as though God had scraped together all the harshest elements of the New England landscape and piled them in a heap, seven or so miles off the coast of New Hampshire. Yet for almost 400 years, people have called this place home. Generations of hermits, entrepreneurs, and romantics have cast their fate upon these forbidding shores, enchanted by the island’s siren song.

Ann Beattie can hum a few bars of that tune herself. As a historian, she’s spent much of her career studying Appledore and the eight other equally bleak islands that together are called the Isles of Shoals, some of which belong to New Hampshire, and some, including Appledore, to Maine. Today she’s passing on a portion of that knowledge to a gaggle of tour-guides-in-training. Her students, mostly older residents of the coastal communities, will lead a few dozen expeditions to the island over the summer—the only chance for casual tourists to visit Appledore. As Beattie leads her charges across the island’s rocky trails, she points out all the things that aren’t there anymore: a flat spot that was once a tennis court; a flooded foundation that used to be a carriage house. The island is littered with ruins, like mementos of old relationships.

The Isles of Shoals have proven adept at reinventing themselves over the centuries. “Whenever there’s a reason for one community to disperse … someone comes along with a new idea, a new reason for people to gather on these islands,” Beattie says. “It’s as though these islands refuse to remain uninhabited. They call to people.”

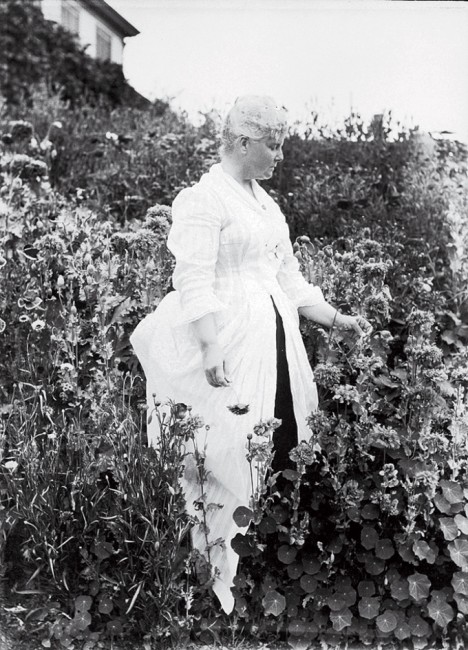

Above: Celia Thaxter in her garden, August 1889.

Photo Credit : MS Am 1272.2, Miscellaneous photographs of Celia Thaxter and Appledore Island (Me.), Houghton Library, Harvard University

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Shoals were home to reclusive fishermen who chased off the ministers sent by well-meaning mainlanders worried about their souls. When the fish stocks thinned, the islands diversified. In the late 19th century, Unitarian Universalists began holding retreats on Star Island (a tradition that continues today). During World War II, the Navy built a spotter tower on Appledore and turned tiny Duck Island into a bombing range. A plan to build an oil terminal on Lunging Island in 1972 fortunately amounted to nothing, given the Shoals’ prodigious history of shipwrecks.

Beattie halts the group at a grassy plain near the seashore. The other islands of the archipelago can be seen stretching to the south. A single boat bobs at anchor. Waves crash. Behind us, a few shingle-sided buildings hug the crest of Appledore’s only hill.

The island has no year-round residents, but during the summer it’s home to the Shoals Marine Laboratory, a joint venture of the University of New Hampshire and Cornell University, geared toward undergraduate education. Throughout the summer, hundreds of college students squeeze into the island dormitories for a week or two at a time to study things like field ornithology or to earn scientific-diver certification.

From here, researchers keep a keen eye on the Shoals’ rebounding wildlife populations. As humans have moved out, seals, seagulls, and endangered terns have reclaimed territory—just one more changing of the guard in a place defined by transformation.

—

But for all the odd hats Appledore has worn, its strangest chapter was during the late 19th century, when the island was a Gilded Age resort. In a fit of entrepreneurial madness, businessman Thomas Laighton built Appledore House here in 1848. It was one of New England’s first resort hotels—and an improbable hit. Laighton tempted visitors to the island by selling it as an exclusive destination and touting the health benefits of breathing sea air. For decades New York socialites flocked here to lounge on the rocks and cough the coal dust from their lungs.

Photo Credit : MS Am 1272.2, Miscellaneous photographs of Celia Thaxter and Appledore Island (Me.), Houghton Library, Harvard University

“The hotel had a billiards room, a music room, a bowling alley,” Beattie says as she marks off the hotel’s boundaries on the now-deserted coastline. “It was amazing.” But perhaps the biggest attraction was Laighton’s daughter, Celia Thaxter, who blossomed into one of her generation’s favorite poets.

She wrote with an aesthetic born of desolation. When she was 4 years old, her father took a job as the lighthouse keeper on White Island, a granite postage stamp at the southern tip of the Shoals. Her childhood was spent alone on a rock in the ocean, carrying a magnifying glass in her dress and pondering anything that washed ashore as though she could make her world larger by focusing on the details.

Her odd upbringing added to her mystique. For a time she was, perhaps, the most romantic woman in a romantic age—a literal Siren, luring dreamers to her island with her effusive verse. They came in droves. Artists and writers made pilgrimages to Appledore to meet her. The likes of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Childe Hassam, and Ralph Waldo Emerson knocked on the door of the humble cottage she kept by the hotel. “Pretty heavy stuff for a girl who grew up on a rock,” Beattie jokes.

Today her poetry is mostly forgotten. “A little too flowery and romantic for our tastes now,” Beattie explains. But to gardeners, Thaxter is still a saint. In 1894, the year of her death, she published An Island Garden, a memoir of her tireless efforts to coax flowers into growing on Appledore. It remains a classic. Thaxter adored flowers the way only a girl raised on a barren rock could, and that passion imbues every page. “Dearly I love to sit in the sun upon the doorstep with a blossom in my hand,” she wrote, “and meditate upon its details, the lavish elaboration of its loveliness, to study every peculiar characteristic of each, and wonder and rejoice in its miraculous existence.”

—

We march down the shoreline to a small stone foundation, half hidden in the grass. A fire in 1914 wiped the island clean. This is all that’s left of Thaxter’s cottage. Beside it, the Shoals Marine Laboratory has reconstructed her garden. It’s shockingly small, just a few raised beds surrounded by a picket fence.

“A lot of people show up expecting a lavish English landscaped garden, because it’s so famous,” Beattie says. But in truth, it was just a small cutting garden—an oasis of color in the blue-and-gray world Thaxter inhabited. “Mine is just a little old-fashioned garden,” she wrote, “where the flowers come together to praise the Lord and teach all who look upon them to do likewise.”

We linger for a few moments, then push on, following a narrow path through a thicket of wind-whipped sumacs and blueberry bushes. Baby seagulls, like fluffy brown bowling balls, peep in the underbrush. This is all new, Beattie explains. After the fire, seagulls claimed Appledore as a rookery. With the gulls came guano, which in turn became soil.

Later, Beattie shows me pictures of Appledore from Thaxter’s time. The island is entirely barren, without a tree or a bush in sight. The hotel and cottages cling awkwardly to the exposed rock like sunbathing crabs. I can’t help but wonder why anyone would have wanted to come here.

This question fascinates Beattie. She jokes that tourists always ask about the same three things: “Pirates, murders, and shipwrecks!” But to her, the most fascinating story is why people came to this lonesome place and why they stayed. What is it about Appledore that hooks people’s imagination and lets it rise from the ashes time and time again?

After a short hike, we emerge into the clearing where Thaxter was laid to rest beside her parents and two brothers. The whole family shared the same struggles on these islands, but each chose to stay, spending the majority of his or her life in this tiny kingdom in the sea. Before the brush grew up, this spot offered an unbroken view of a swath of the New England coastline, from Cape Ann in Massachusetts to Cape Neddick in Maine.

Glimpsing that view gives you a fleeting sense of why someone might fall in love with this place. The mainland is just far enough away to make you feel as though you’re someplace else—a world that’s small, but entirely your own.

“Many troubles, cares, perplexities, vexations, lurk behind that far, faint line for you,” Thaxter wrote. “Why should you be bothered any more?”

To attend a day tour of Celia Thaxter’s garden, visit: shoalsmarinelaboratory.org/event/celia-thaxters-garden-tours. For other day trips and retreats visit: www.shoalsmarinelaboratory.org/.

Justin Shatwell

Justin Shatwell is a longtime contributor to Yankee Magazine whose work explores the unique history, culture, and art that sets New England apart from the rest of the world. His article, The Memory Keeper (March/April 2011 issue), was named a finalist for profile of the year by the City and Regional Magazine Association.

More by Justin Shatwell