Walking the Entire New Hampshire Seacoast | A Short Coast with a Long Story

The New Hampshire seacoast encompasses only 13 miles. A day’s walk, however, proves that it’s long on character and characters.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanI’m walking the edge of New Hampshire from Massachusetts to Maine, and I’m having a hard go of it. The tide is in. It’s perfect for fishing boats and surfers. On the horizon I count 23 trawlers, their silhouettes like an eye chart, some with distinct prows, others faint. Closer, a cluster of surfers bask on their boards, sleek as seals in their wetsuits. However, the swells keep washing over the beach, and I’m not keen on hopping from rock to glistening rock, so for now I’ve retreated to the sidewalk between two extremes—this glittering ocean off my right shoulder, and off my left, the rumbling engines of Route 1A—the coast-hugging road with its current of summer traffic.

Others intent on enjoying America’s shortest coastline, regardless of tideline, are also improvising. One bikini-clad woman has abandoned her chair by the seawall and climbed atop it to read her novel. Another sunbather, undeterred, has planted his chair amid the mere inch of beach and inscribed CHEF’S DAY OFF in the slaked sand beside it. Farther on, a young couple pauses beside their pushcart of gear to gaze at the mesmerizing unfurling of surf.

New Hampshire’s coast is only 13 miles long, the shortest of all 23 states bordering an ocean. Even if you toss in the Isles of Shoals, a group of islands about 8 miles off the Rye shore, half of which belong to New Hampshire, their combined 5 miles of oceanfront boosts New Hampshire’s lump sum only to 18 miles—a drop in the bucket compared with Maine’s 228 miles, Massa-chusetts’ 192 miles, or even Rhode Island’s 40. (And we’re talking just “general coastline” here. If you take these states’ many islands, bays, and so on into account, their “tidal shorelines” encompass hundreds more miles.) Yet, lest you imagine New Hampshire’s petite landfall as one contiguous sandy swath, I can attest that it’s not.

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

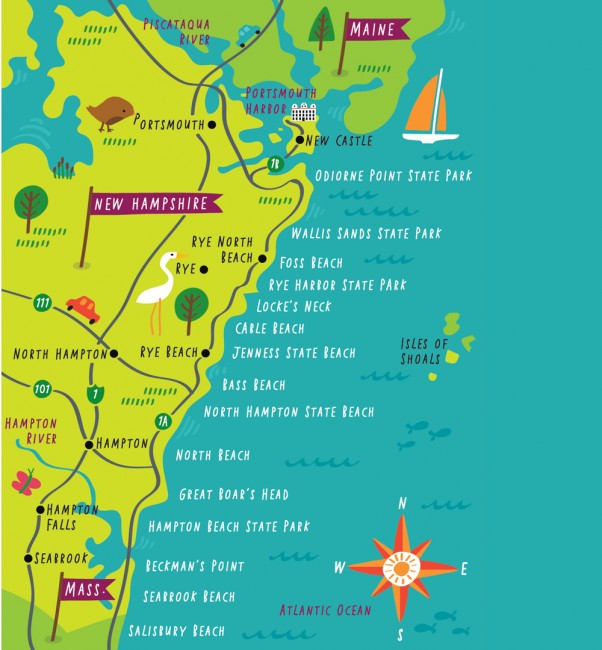

Approaching the New Hampshire Seacoast region from the south, as I did, arriving by a side street in the border town of Salisbury, Massachusetts, and following a slender footpath through the dunes to where the Atlantic Ocean nuzzles the North American continent, you’ll meet the first of several beaches tucked between rocky promontories—a score of unique sites, like the beads and pendants of a necklace.

Venturing north from the Massa-chusetts border there’s Seabrook Beach and Beckman’s Point; followed by the Mile-Long Bridge over the Hampton River to populous, hopping Hampton Beach; which is followed by Great Boar’s Head, and North Beach, and Plaice Cove, and North Hampton State Beach; then Little Boar’s Head, Fox Hill Point, and the crescent of Bass Beach; followed by Philbrick Beach and Sawyer’s Beach, which drifts into Jenness State Beach; then Cable Beach, and Locke’s Neck, and Ragged Neck Point, and Rye Harbor; on to Foss Beach and Concord Point; along Wallis Sands and Odiorne Point, with still more coast to cover, if time and tide are on your side.

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

For my day’s walk, I’ve come equipped with a pair of sneakers tied together by their laces and slung over my shoulders, and socks stuffed into my satchel. Also, I carry a map, a clementine, a quarter-pound of trail mix, a bottle of water, sunscreen, and a pad and pen. When you’re walking the beach, miles seem like a strange form of measurement. Better to walk toward something big looming in the distance, and reach it and rest, and then pick something else and walk to it, and then pick another, and another …

Since early this morning I’ve been meeting each place this way, one step at a time, by eyeing a distant landmark—the Mile-Long Bridge over the Hampton River, and from the bridge to The Surf, a five-story condominium overlooking Hampton Beach. And from The Surf to the snout of Great Boar’s Head. I continue setting out again for rocky outcrops, a distant flagpole, the crescent tip of a beach, a cluster of fishing shacks, then stalking off in its direction. Upon reaching it, I rest, and then shove off again, learning along the way that this short coastline has a long story.

—

Photo Credit : Nate Padavick

In 1888 historian and Hampton Beach native Lucy Dow described New Hampshire’s disparate coastal terrain in her book Beautiful Place of Pines. She portrays “the waves … [throwing themselves upon] a rampart of rocks, stretching far northward, and forming, in all ordinary weather, an effectual barrier,” in contrast to the tempting beaches where “one has but to lie prone … with umbrellas spread for protection from the sun and wind, and look down upon the dancing, flashing waves sweeping shoreward … till the roar tones into a gentle murmur and sky and wave and shore melt together in misty vision under closed eyelids.”

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

Wherever the beach ends and the cliffs or rocky spits begin, I hit the pavement. I wish it were contiguous, but coursing northward, I feel as though I’m following as best I can the sea’s bite marks, the shore’s serrations. I trek across wet sand, sidewalk, and rock, much of which is now managed as seven state properties—Hampton Beach State Park, North Beach, North Hampton State Beach, Jenness State Beach, Rye Harbor State Park, Wallis Sands State Park, and Odi-orne Point State Park—which are interspersed among town beaches.

Native Americans called this shoreline region “Winnicunnet,” meaning, “beautiful place of pines.” According to Dow, this coast was “an unbroken wilderness trodden only by savages” who “lay basking in the sun upon the sands, or launched their frail canoes and shot out fearlessly over the billows.” In 1974, archaeologists from the University of New Hampshire excavated a mile or so inland along the Hampton River and found bones, shells, tools, stone weapons, and clay pots—evidence that led them to surmise that this coast has been inhabited for at least 4,000 years.

As I descend from the sidewalk back to the sand and make my way amid the throngs on Hampton Beach, I pass a 5-year-old with a tousle of red hair murmuring to himself, “Nothing can destroy this.” I stop to watch as he overturns his bucket of packed sand and carefully lifts it, revealing a stout fortress. High tide is just beginning to recede, and his declaration is, if not entirely accurate, at least in tune with the town’s spirit.

Hampton, one of New Hampshire’s four oldest towns, celebrated its 375th anniversary in 2013. Two miles inland from this child’s castle, there’s a rock dedicated to the 1638 founders who “settled in the wilderness … to plant a free church in a free town.”

I wonder how those founding families—the Foggs and the Batchelders, the Moultons and the Laphreys, the Gookins and the Philbricks—would feel about their enduring town’s unfree parking. In 1956, to offset the cost of constructing a 3,300-foot-long sea wall stretching from Hampton Beach to Great Boar’s Head and another bit from Great Boar’s Head to the end of North Beach, 2,300 beachfront parking meters were installed, and remain today—one thing I needn’t worry about as I hoof it north.

—

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

At first, the day is cloudy, the sun caught in a net of high clouds. Later, the clouds wear off, the day grows bright and clear, and as I walk I observe hundreds of people fully spread out on their towels or in their recumbent chairs, basking like morsels on a cocktail napkin, offering themselves, it seems, to the sky itself. Meanwhile, the surf pushes and pulls on shore, a soft rowdiness.

I keep thinking, That’s Spain across the way. Other than the Isles of Shoals, it’s the next place out there, and the waves have come all the way over to fall on our shore.

Which sounds like I’m getting a bit precious, except: Way up ahead, on the far side of Jenness, there’s Cable Beach, named for the transatlantic telegraph cable laid down here across the seafloor in the summer of 1874, connecting this bit of Rye coast up to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, and thence across to Ballinskelligs Bay, County Kerry, Ireland. And oh, the messages this wrist-thick cable has carried across 3,104 miles of ocean. I learn that during the lowest of tides, you might glimpse vestiges of the old cable snaking through the “Sunken Forest,” where an ancient conifer grove once stood, before the glaciers of the last Ice Age sheared them away.

—

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

By the time I reach Jenness State Beach, morning has ebbed into afternoon, and now the tide is out. Generously out. It’s as if the sea has courteously moved over to accommodate the influx of people who are vying for places to spread their towels, unpack their gear, and lie prone to misty visions. Along my journey between firm sidewalk back to doughy sand, I’ve passed shell gatherers, plucking finds as though recovering pieces of a shattered vase, and stone pickers raking the pebbles around with their toes to churn up the best ones.

I’ve come upon John, a State Parks employee wearing a yellow polo shirt with his name badge; he’s tweezing bits of plastic and paper with his reacher/gripper, and plunging them into his trash sack. And Lance, the lifeguard, whose 9-to-5 involves manning one of the 18 highchairs spread out over miles of sand. And Gloria and Marsha, sisters in their late fifties, who’ve been returning to this shortest coast all their lives—first as children, later as young mothers, and now, “just chillin’.” Marsha says of their beachgoing habit, “We come in with the tide and we go out with the tide.”

I meet Ed, a retired steelworker, whose self-assigned duty is picking up after the public. On sunny days and on rainy ones, he walks the amber expanse, packing detritus into his garbage bag. “How bad?” I ask. “You wouldn’t believe what people leave,” he tells me. “Dirty diapers, juice boxes, a lot of plastic.”

Considering what might be found, the most material I’ve encountered is dark wisps of seaweed, which centuries ago was a commodity in such demand that the town of Hampton posted an ordinance in 1883 announcing that it would prosecute anyone who took it from the shore under cover of darkness. Meanwhile, the only warnings I find on my foray north are the yellow flags luffing by the lifeguard’s chair. “We always hang them,” Lance says. “Yellow means moderate danger—which is true, there’s always danger—but there’s no rip[tide] today.” That, and the metal sign at Northside Park warning beachgoers not to mess with the seals as they “haul out on the beach to rest.”

Yet in lieu of litter and danger and seaweed stealers, at intervals I find items that seem to epitomize the spirit of this place. For example, there’s a single sandal with silver straps nestled in the sand, as if it had switched allegiances from the foot to the shore.

Farther on I spot a shiny red tricycle resting all alone by the seawall. Its tassels spray from the handlebar ends and pedals spread on either side of the front tire. Just three steps down from the wall, where the surf-infused cobbles make a skittling sound as the water recedes, the tricycle rider is meeting the Atlantic Ocean, perhaps for the first time, as her father bends over her and lifts her up each time a wave kisses her shins.

And then there’s a yellow toy shovel lying facedown in the gravel parking lot of Rye Harbor State Park, which also contains a granite obelisk celebrating Captain John Smith, who mapped this coastline on his voyage 400 years ago and gave it a name: “New England.” Could he ever have imagined all of us here today, playing, lifeguarding, picking up trash? I’m startled at how close I’ve come to the beginning of this country; inspired by Smith’s voyage, the Pilgrims sailed six years later. Smith described this continent as a place where a person who could use “a pick axe and a spade” would fare better than “five knights.” And by consequence, I suppose, he anticipated the small hand of the boy who recently plied this yellow shovel.

—

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

I’ve paused upon a granite bench inscribed Cherish this day, and, having peeled the rind off my clementine, I’m savoring each segment. Ahead of me lies Wallis Sands State Park, a former lifesaving station; Odiorne Point State Park, with its remnants of gun turrets from World War II; the Seacoast Science Center, with its extremely rare orange lobster; Wentworth by the Sea, the grand hotel on New Castle Island, where Japanese and Russian delegates stayed while meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt’s representatives in Portsmouth to hammer out a peace treaty in 1905; and still farther on, the bridge leading to Kittery, Maine.

But those are a few hours and thousands of steps away. I think of Marsha’s observation—“We come in with the tide and we go out with the tide”—and how we beachgoers are, year after year, day after day, a corresponding tide, arriving in waves as we fill up parking spaces, spill across the sand with towels and umbrellas, brim against the water’s edge. We flow into these unique parcels of our country’s shortest coast.

And then, eventually, we stand up, brush off the sand, collect our buckets, trundle our surfboards, scoop up the tricycle, stash the sandal—and take one last look at the mesmerizing surf unscrolling on shore. Then we, the high tide of humans, begin to trickle back out. Or, in my case, keep strolling north.

Nice article!

This is a very good article.

Loved this article!