Bucksport, Maine | The Town That Refused to Die

When the paper mill that had defined Bucksport, Maine, for eight decades shut down just before Christmas 2014, the town, like others before it, could have withered away. Instead, something else happened.

Though the Bucksport mill was largely demolished after being shut down in 2014, its power plant still defines the landscape of this Penobscot River town. For many residents, seeing the smokestacks means they’re home.

Photo Credit : Gabe SouzaThe Last Shift

You learn what you’re made of not when life is good, but when the ground beneath your feet gives way, and you are left afraid and uncertain of what to do. In the past year, I have found the same may be said about a town.

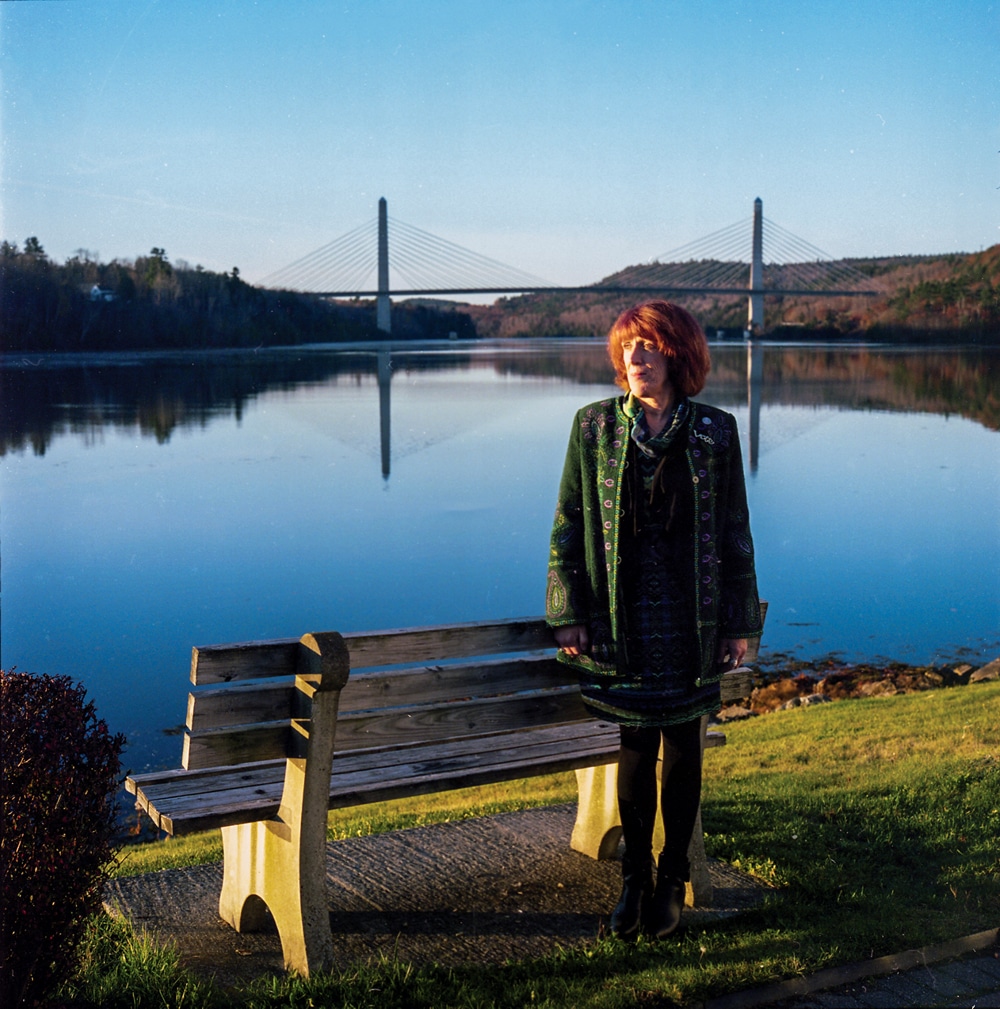

The one I am talking about is Bucksport, Maine. About 4,900 people live here, in modest, well-kept homes set back from the east bank of the Penobscot River where it spills into the deepwater bay. Important things have always been made here. Before the turn of the 20th century, shipbuilders lived along the river, and when Robert E. Peary set out for the North Pole, he sailed on the Roosevelt, built on neighboring Verona Island, with a Bucksport mariner as chief engineer.

At the northern edge of town, on a spit of land known as Salmon Point, a paper mill was built in 1930 where a tannery once stood. The site earned its name from the spawning runs that once churned the river thick with fish. Even with the Depression settling upon the country, Bucksport had resources needed to make paper: water, forests, and the newly constructed Wyman hydro dam in Moscow to power the immense machinery that transformed pulp into paper. There was a port for ships to bring supplies in and take tons of paper out. And there were people hungry for work.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

The men and women who lived in Bucksport and the rural hamlets that rimmed the town came from rugged stock: They were loggers, farmers, fishermen. Their families were large and self-sufficient, and they put meat on the table by knowing how to shoot game and how to fish on the lakes and ponds that rippled through the countryside. They would work themselves to exhaustion if asked—and they were.

Over the decades Bucksport became known for producing the finest lightweight coated paper in the world, paper that was used in such magazines as Time and Sports Illustrated and Good Housekeeping and Newsweek and catalogs like L.L. Bean and Sears and Victoria’s Secret and Avon. The boast was that any American who read magazines touched paper that came from the skill of Bucksport papermakers.

Hundreds of thousands of people pass by Bucksport every summer, on their way to Bar Harbor or Acadia National Park or the Blue Hill peninsula. They view the town from two tourist sites across the river: 19th-century Fort Knox, the largest fort in New England, and the Penobscot Narrows Bridge, which has the tallest bridge observatory tower in the world. They ride the tower’s elevator up 42 stories, and from that height Bucksport appears as a miniature village against the dark water, the smokestacks of the mill stabbing the sky. Crossing the river, they reach the town’s lone stoplight. A right turn leads to Down East tourist towns; left, to Bucksport. Few turn left. It was a point of pride for many residents that they did not scrub sidewalks for summer visitors. In Bucksport there is neither high season nor low season. There is football and hunting season, snowmobiling season, fishing season, summer-camp-by-a-pond season. It was always papermaking season.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

I learned much of this in the summer of last year, just before the 225th anniversary of the town’s founding by Jonathan Buck, which would be celebrated at the annual Bay Festival. It had been two and a half years since the paper mill was shuttered by its most recent owner—an out-of-state company called Verso—a decision that came with no warning and left the town reeling. Some 570 workers, half as many as had once worked at the mill, lost their jobs.

I had been invited to give a talk on the spirit of community at a weekly summer event called Wednesdays on Main, held at the historic red-brick Alamo Theatre. Community was not an abstract topic in Bucksport that evening. When a mill town loses its mill, it loses not only the core of its tax base, it loses its security, its future, its sense of who it is. “This was traumatic,” says Tom Gaffney, a psychologist who has tended to local families since the early 1980s. “There was numbness. Fear. They all asked, ‘What are we going to do now?’”

Photo Credit : Ashley L. Conti/Bdn

Everyone had seen what happened just 80 miles north when Great Northern Paper left town, wounding Millinocket and East Millinocket seemingly beyond recovery. Laid-off workers pulled up stakes, their houses on the market for $25,000 or less. Families were uprooted. Schools lost their students. Across the country, that’s how the story usually goes when a company town loses its company.

When my talk ended, a tidy procession of people from the audience followed me up the street to a reception at MacLeod’s, a restaurant that on Thanksgivings past had delivered more than 1,000 turkey dinners to mill workers round the clock, as papermaking did not stop for a holiday. Afterward, we continued to a new café called Verona Wine and Design, where we sat on an outside patio under twinkling lights.

They said the mill closing should have crushed the town—but didn’t. Now something remarkable seemed to be bubbling up, even as the ground remained unsteady. The mill and its 274 acres had been bought by a Canadian metal recycling company, and the town had little control over what might happen next. What people could control was how they reacted.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

They told me that listening to each other had become an urgent task. A local poet was collecting memories of the mill where her father had spent his life and was putting them into a book. Organized committees and teams of volunteers were listening to neighbors to find out what they hoped Bucksport might become. Past, present, and future were swirling around one another in a web of voices; sometimes they all got tangled. People said they were still learning how to seed hope where despair could easily take hold. They were still learning how to move ahead while the carcass of the mill was visible to everyone.

When the night ended, I said I would return. I’d listen too. It is the story I tell now. It begins with an ending, December 17, 2014, one week before Christmas Eve.

—

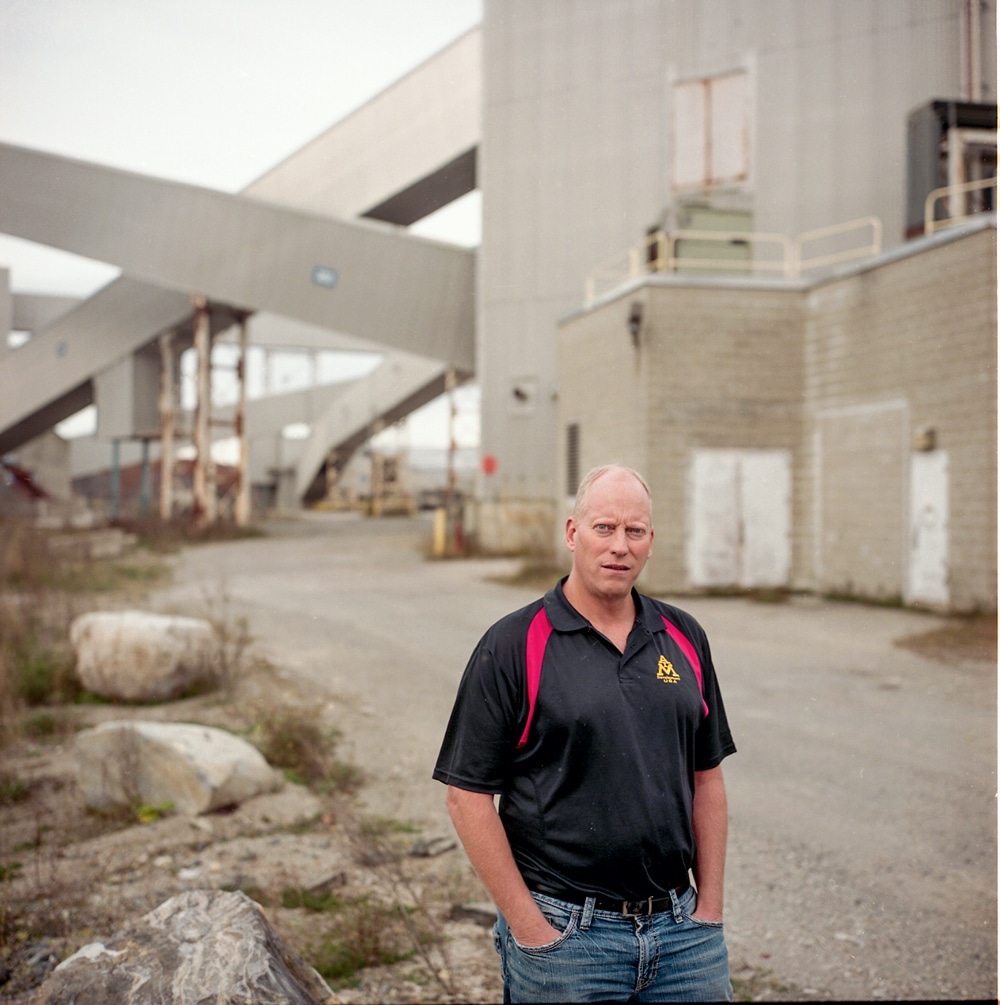

Everyone in Bucksport knew the mill would close one day—they could see what was happening in a world where people read magazines on their phones—but they thought it was still years away. For Danny Wentworth, whose family’s papermaking roots go back more than 80 years, here is what that meant. He was driving home from the Fryeburg Fair on October 1, 2014, when his cellphone rang. His supervisor said the mill was closing. Forever. Wentworth threw the phone against the dash and yelled, “We’re done!” Panicked calls and texts flew back and forth across the towns that were home not only to mill workers but also to many who depended on the mill: loggers, truck drivers, shopkeepers, town officials who managed the local tax rate. Pretty much everybody.

Danny remembers the final weeks this way: coworkers struggling with anxiety; the bitter reality that the mill had been sold for scrap; shutting machines down one by one, like the lights of a city going out. He knows it’s impossible for outsiders to understand the depth of feeling you can have for a machine that you’re with as much as you are with your family. “When I shut down No. 1 paper machine, I got real emotional,” he says. “It was the first one to start up when they opened the mill. That was my baby.”

He tried to stay hopeful. But even as rumors spread that other paper companies wanted to buy and reopen the mill, “we all knew a scrapper was coming. We’d see them come in with their dark suits, and they seemed to be drooling over the brass in the machines. And we were all thinking, This is what we’ve done our whole life.”

On the final shift of the last day of papermaking in Bucksport, Danny walked past the main gate just before 7 a.m. On this day, it was quiet. The scents of ground spruce and fir pulp swirled with chemicals had all but disappeared. He had eight hours to linger, with little to do except brood about the legacy he was leaving behind.

His maternal grandfather, Arthur Wight Sr., was a New Brunswick native who came to Bucksport with his wife and children from Berlin, New Hampshire, and found work when the Maine Seaboard Paper Company opened the mill here in 1930. Danny’s father, Charles Wentworth Sr., started at the mill after graduating from Bucksport High School in 1942, then went to war in the Pacific. When he came home in 1946, he went back into the mill, now owned by St. Regis, where he would spend the next 40 years. He helped build No. 4 paper machine, then supervised the flow of paper stock. When Danny and his siblings were young, he would sometimes sneak them past the gate on nights when he had to come in to deal with a problem. To the children, with the rumbling noise and clouds of steam, it was a strange and exciting world.

For a long time, the mill was Danny’s only real job. He graduated from Bucksport High School, tried college for a year, and then in 1981, at age 20, he came home and “went into the mill.” That was how you said it—“went into the mill”—as if it were a world unto itself. And it was. You spoke paper mill language: beater rolls, wet end breaks, drum barking, groundwood, swipers, riggers. Even with ear protection, the noise was so loud and piercing that you and your coworkers communicated with hand signals that would be a foreign code to much of the outside world. You shared the certainty that accidents happen and that machinery moving at high speed is unforgiving—“a lot of thin ice in a mill” is how they said it. You earned some of the highest wages in a poor state, and the heat, noise, bone-wearying hours, and lifetime of disrupted sleep cycles were the price you paid. In return, you escaped to the woods and camps in trucks, snowmobiles, and four-wheelers that took you to fresh air.

The mill was humming when Danny first came and would soon swell to 1,300 workers. His father told Danny he could expect to be there for a lifetime. Danny’s brother, Jamie, came on later; with their uncles there too, it was a family affair. In time, Danny rose to become tender on No. 1 paper machine. He was there when Champion International bought out St. Regis, and when International Paper forced Champion out, and when Verso took over in 2006. Every day he drove four miles across the bridge from Verona Island feeling the calm certainty of being where he belonged. Love is not a word used loosely about this work, but he’ll say to anyone who asks, “I loved it there.”

On December 17, in the final hours, Danny felt “like a family is breaking up. We are connected. And the connection is about to break.” Later he would search for words to describe the days of demolition that followed. The dust of crushed concrete swirling like clouds. Seeing the gigantic paper machines ripped apart by excavators that looked like dinosaurs, then loaded onto railroad cars and carted away by AIM, the metal recycling company that now owned the property. The sound of metal clanging against metal as the cars rolled out of town.

—

He tells me this as we sit at a table on Bucksport’s mile-long Waterfront Walkway. It is a warm afternoon in September 2017, nearly three years since Verso announced the mill would close. Danny is soft-spoken, friendly, a youthful-looking 55. He says that in the first months after the mill closed, he could not sleep. He was hired as a sander at Hinckley Yacht on Mount Desert Island but developed symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. “I never felt old until I went there,” he recalls. “They called me ‘the old guy.’”

He eventually was hired by a tissue-making mill near the Canadian border, more than 100 miles away, and retrained to run their machines (the man who hired him had also worked at the Bucksport mill). He keeps a small apartment up there and drives home every few days. His wife works as a nursing assistant at Blue Hill Hospital. He has two grown sons who live within an hour’s drive: One is a policeman, the other is in the oyster business. His third son, Andrew, was a standout pitcher for Bucksport High whose winning hit in the Eastern Maine baseball championship was one of the proudest moments of Danny’s life. He shows me that on the back window of his Toyota 4Runner, in fact, is a decal with Andrew’s jersey number, 19.

A few months after the mill shut down, Danny’s mother died. His father followed soon after, and then 10 days later Andrew was gone too. “Time passes,” Danny says, “it gets a little easier. But there are days when it hits me.”

Danny is not someone who talks easily about tears. He tells me that when he and his brother walked out of the mill and through the gate for the last time, with townspeople waiting in the cold rain to applaud and hug them, he held it together. Then he saw Ed and Pat Ranzoni waiting for him. Ed had been his high school baseball coach. Danny did not expect what happened when Pat put her arms around him. He began to cry, for himself; for the end of 35 years of knowing where he belonged; for his friends; for his father, who would sit by the window and look out at the smokestacks without smoke until the day he died; and for the ground giving way beneath his feet.

A Daughter of the Mill

Within a few days after Bucksport heard that the mill would shut down, two things happened that would come to be seen as igniting the town’s resolve to survive. One was about the future, the other was about the past. They would come to intersect in a way that will undoubtedly change the town forever—but this was impossible to know during that grim October four years ago.

The first thing happened when about 70 townspeople came together at the Alamo for the screening of a documentary about the restoration of a gristmill that now housed the Lost Kitchen, one of Maine’s most acclaimed restaurants. The evening morphed into a kind of emotional pep rally: We have to find our own way. We won’t let our town be broken. People who had arrived somber and in shock, fearful they would be forced to move, left buoyed by what they would come to call their “Night of Hope.” One woman whose husband worked for the mill for three decades told me she knew then they would “stay and defend our town, much like a sibling when his brother or sister is threatened. We wanted to help our community go forward in a new way.” Within months, there were so many community groups forming in Bucksport that town officials joked they needed a duct tape committee to hold them all together.

The second thing happened when Pat Ranzoni was in her car, crossing the river into Bucksport and looked out on the mill. Earlier that year, the town council had proclaimed Pat their “poet laureate for life.” She was known for her bone-deep images about the lives of “my people”—a phrase that encompassed Native Americans, mill workers, and rural Mainers who lived on the edge. In one poem she writes of being a teen, wanting to accept a party invitation / from friends. Management families. / ‘Who do you think you are?’ her / bitter father instructed. / She hadn’t understood.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

As Pat looked at the mill that day, two words came to her: “Still Mill.” And a mission was born in her to create a book with that title, a book that gathered the memories of mill workers and their families—nobody would be able to dismantle and cart those away. “I didn’t know how I was going to do it,” she recalls, “just that I had to do it.” Last summer, Pat published the anthology Still Mill: Poems, Stories & Songs of Making Paper in Bucksport, Maine, 1930–2014. Of her title, she writes in the preface: “STILL in that it would soon be quieted. STILL in that as long as we live and after, as long as stories are told, the mill and the people who made it what it was—with all its flaws and wonders—shall live on.”

Though Pat was shy about talking with me—“I come from a culture that if a stranger shows up, you run and hide,” she says—we meet up at her home on a bright September afternoon. She lives with her husband, Ed, about four and a half miles outside town on the rustic homestead her parents moved to when she was a teenager. Even out there in what people called “outback,” she could hear the mill’s “rumble and roar.” She and Ed bought the place in 1970, when her father’s body was “breaking down” from his work in the mill.

Pat pushed past 70 a while ago and recently had her knee replaced; there is pain. While we talk, she rests on a cot beside a window that looks out on gardens and fields. Ed knows his way around the woods, and a deer skull from a hunt for the winter’s meat adorns the wall in a room dominated by a great stone fireplace. A small red pan hangs from a rafter to catch a leak. “There’s some leaks you never can catch,” she says.

I hold Still Mill, the culmination of nearly three years of “listening as hard as I could, for as long as I could,” Pat says. She signed copies in July at the local bookstore until her hand ached, the line stretching out the door, with proceeds going to the historical society. Wherever she went, people thanked her. One woman said that her father could read only three pages at a time before tearing up. I ask Pat why her readers might react that way. “It’s the recognition that somebody values what they have done, that it will be remembered,” she says. “Many probably thought they’d have their private memories but they would be lost [to the world] forever.”

To gather stories for the book, she put out a call through newspapers, friends, family, schools, and churches. Danny Wentworth posted her request on Facebook. A modest grant came through to help fund the project. Submissions started coming in, many handwritten. One woman told of hearing blasts of dynamite when the mill site was first cleared. Another woman wrote about the heat—“up to 120 degrees by paper machines”—and added, “Once I broke a finger and didn’t say anything, feeling I needed to tough it out and be a man.” Another resident lamented that there would be “no more stopping for workers crossing the street, after a long hard shift. A small courtesy which bound us together as a community.” There were also hard truths shared by many mill families. When Pat asked for memories of Thursday paydays, when grocery stores cashed checks, a mill worker’s daughter wrote, “Oh, no. Not on your life. Paydays meant a gallon of wine and a bad night for the family, and I won’t go there.”

When people were reluctant to write, Pat went to them, and listened. “People would just start talking,” she says, “and keep going.” She worked until nightfall, and when sleep eluded her, she would sit up and write more. Pat would pin the pages to clothesline strung across the living room, moving them around until a story unfolded that said, This is who we are. This is our culture. Of the finished book in my hands, she tells me, “This is the most important work of my life.”

Pat’s father, Percy Smith, had been one of the mill’s riggers, the construction crew. He would clear snow, drive trucks, repair whatever broke down, load and unload ships. He came from what Pat calls “deep poverty,” the kind that compelled him to leave school after eighth grade. Pat herself holds complicated feelings about the mill. She saw the toll it took on her father, but she also knew his pride—his children would not go hungry.

Pat harbors no romantic nostalgia. She tells me about a visit she once made to the mill. “I climbed up these metal stairs, and it got louder and louder, and when I got to the top there were three of my classmates tending a machine, and it was so loud. I tried to smile. I felt like I’d gone into the diamond mines. And I thought, They have lived their lives like this.”

And yet. As the hours pass, listening to Pat, her voice soft, gaze steady, I think of what Joan Didion once wrote: “A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively.” Every page of Still Mill is infused with deep respect for the men and women who walked through the gate day after day, year after year. Pat wants their lives remembered.

She frets that the rush to create a new, thriving Bucksport might eclipse what the mill workers’ lives had meant. She admits she is struggling with the influx of well-meaning programs, some coming from outside the community.

She has baked me a fresh wild blueberry pie, and as we sit at the table, Pat Ranzoni, poet laureate of Bucksport, wonders aloud if the past will still matter, or simply be swept away. Will there be a place in this still-to-be-determined Bucksport for someone who long ago laid claim to its memories?

Every Voice Matters

When I went back to Bucksport last fall to see how the town had kept its resolve, no matter whom I talked with, the conversation always came back to Susan Lessard.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

Lessard had been hired in late summer 2015 only as the interim town manager. The energy that had emerged on the “Night of Hope” was still bubbling up but tempered by knowing the town had no control over what the mill site might become. The future rested in AIM’s hands. “It was like being tied to a runaway train,” one woman told me. Lessard had spent 22 years as a town manager, first on the island of Vinalhaven and then in Hampden, five miles south of Bangor, and was hoping to ease into the role of a consultant. The two previous town managers for Bucksport both left after short tenures, and Lessard had signed only a 10-month contract. “I was the dust-settle girl,” she says.

A lot of dust settled—and Lessard stayed on permanently. “I will tell you, at first I was ashamed,” she says when we meet in her office in Town Hall, set on a rise above the river. “I was born and raised 20 miles away in Belfast and had driven the bridge a million times. But I never looked beyond Bucksport as a mill town. And I never looked beyond that to see everything that was here. I had no idea what Bucksport was. And I stopped to see.”

When she looked, here is what she saw: a brick-lined river walk, a nationally known film archival center, hiking trails, a tradition of championship high school teams, an ice cream stand that had been a fixture for more than 60 years, a bookstore with a buff-colored cat that cozied on readers’ laps, a community that bestowed a “golden snow shovel” to the business that did the best job of keeping the path clear after a storm. And there were townspeople eager to roll up their sleeves to find a way for their town to survive. Their infectious energy gained notice beyond Bucksport’s borders. At one community development meeting, a state official remarked, “You guys are the standouts from all towns who have lost their mill.”

Bucksport had also benefited from the prescience of a previous town manager, Roger Raymond, who had served for 27 years before retiring in 2012. Long ago, he had asked what would happen if the mill shut down, draining 70 percent of the town’s tax revenue with it. Gradually he had taken steps to wean the town of that dependence. By 2014 the town had saved more than $8 million in its rainy-day fund—so when the storm hit, it was ready. Property taxes, which were among the lowest in the Midcoast, needed to be raised, but only a little. Lessard tells me it helped that “when the mill closed, it closed. It stung, but it was over. We hadto move ahead.”

Less than a year after she arrived, she helped persuade the town council to fund a local director for a project called Community Heart & Soul that originated with the Vermont-based Orton Family Foundation. Its essence—adopted by several other struggling Maine towns—was to connect with people, listen to their stories, learn what they most wanted to see happen in Bucksport. With financial and organizational support from the foundation, Heart & Soul took over the former Rosen’s Department Store, which had been rooted on Main Street for nearly a century. Its windows became plastered with note cards filled with the ideas and wishes of townspeople. “It’s grass-roots,” says Lessard. “It’s listening to people who don’t usually have a voice, like the guys who hang out at Dunkin’ Donuts each morning.”

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

Hundreds of ideas flew about like so many birds taking flight. Some were practical: more affordable housing, a long-term-care home, more benches along the river walk. Others were fanciful: a huge indoor water park at the former mill site, for instance. More than just ideas, Heart & Soul came to symbolize a place where people were asserting ownership: This is the town we want. Their commitment was palpable.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

Then, late in 2016, when nobody knew what lay ahead for the mill site, an entrepreneur from Portland came to see Susan Lessard. He was looking for a town that had specific physical advantages. And, equally important, he was looking for a town with spirit.

—

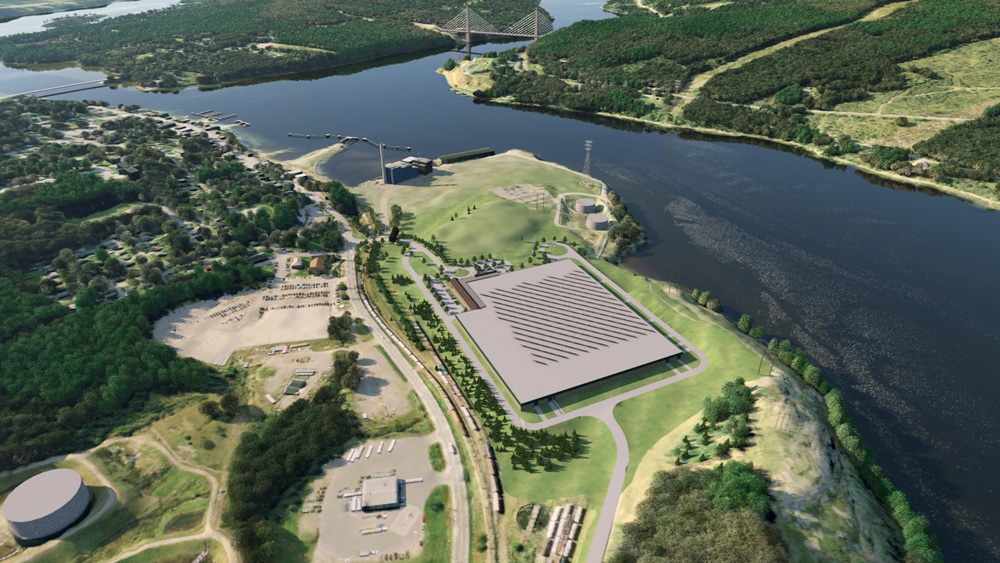

If everything works out the way people hope, one day 10 or 20 years from now, historians will look back on how Rob Piasio and Whole Oceans came to Bucksport and built one of the leading land-based salmon production operations in the world, and it will all seem as if it was meant to be.

Piasio, who grew up on Casco Bay in Yarmouth, Maine, had become obsessed with aquaculture while working in Europe as an investment banker. He came back to his home state to make his dream a reality, founding Whole Oceans in Portland in 2014. He had a plan and backers, but he did not have a location. For the next several years he scouted sites where he might raise thousands of salmon—not in ocean holding pens, but in special buildings using innovative technology, with clean water recirculating constantly. He concentrated his search on a 140-mile-long Maine coastal corridor that stretched roughly from Hallowell to Bucksport and beyond. The site would demand both fresh water and salt water, and ready access to transportation lines to bring salmon eggs in and adult salmon to market. He culled his list to about 18 potential places.

When Piasio first came to Bucksport to kick the tires, he met in secret with Lessard and economic development director Rich Rotella. He toured the mill site: There was the salty mouth of the bay, there was a pipeline to Silver Lake. There were train tracks. And good access to power. He left. He kept looking. He wanted more than a physical site—he wanted to be sure there was a “cultural fit.” He was drawn to Lessard’s optimism about the town and the hope that hung in the air, but when you’re about to spend tens of millions, you move with caution.

Then, months later, he read Still Mill. In its pages he found a story by the town barber whose father had been badly hurt in the mill. The worker refused to sue, saying the mill had given not only him but his friends good jobs. He read about lunch baskets being passed down from father to son. He read how a town lined the walkway to hug the workers leaving their jobs for the last time. He read that “nothing is impossible when hearts and minds work together as one.” He read how Pat Ranzoni looked to the mill crossing into the river and knew what she needed to do. “I was left with profound observations,” he tells me. “It’s the story of a community and how it changes and how it was formed by its mill. I said, ‘Wow! Here’s an opportunity to write a new chapter.’” He had found his cultural fit. He told Lessard he wanted to be the town’s next 100-year-old company.

On December 17, 2017, the third anniversary of the final shift, the town council honored Pat Ranzoni for the gift she had given everyone with her work. At the time, few people knew about what was coming. One was Susan Lessard. She told Pat that her book had been a way to not forget the legacy of the mill and its people. “This book helps provide closure through understanding,” she said. She called Still Mill the “springboard to the future.” Tears flowed as the past, present, and future entwined in a single moment. Two months later, in early February, Whole Oceans officially announced its agreement to build on the former mill site.

—

Late one afternoon in early June of this year, I walk north along Bucksport’s waterfront, toward what remains of the paper mill. The sun is strong. Rose bushes press against the bank. Water laps against the rocks. Seagulls swerve over the bay and a loon dives maybe 100 feet out in the water. Weeds grow tall along the train tracks. A young woman jogs by. I walk past the year-old art gallery that anchors the downtown; a few years ago it was an empty eyesore. I pass the new Friars’ Brewhouse Tap Room, where two Franciscan brothers brew craft beer and make the food. Its “Papermakers Lunch” is a special. I dined there the night before, and Danny Wentworth came in. He said he was glad that soon most of the mill would be gone.

Walking along the pathway, I come to an interpretative panel titled “Looking to the Future.” According to one section of text, the paper mill’s “sudden closing in 2014 pierced the heart of the community. But with … strength and determination … the citizens of Bucksport have embraced the reality of ‘going paperless’ and transformed the mill’s passing into a catalyst for new growth and prosperity for the future.” Beneath this is a poem by Pat Ranzoni about the “ancient power” of the Penobscot River.

Community Heart & Soul ended its two-year program just a few months before my visit. Now the Rosen’s storefront stood empty. The hundreds of comments that had been collected were reduced to a final 82 that were given to the town council to consider. They included a desire to start a farm-to-school food program, a community garden, a dog park, cross-country ski trails, community art classes, bicycling and running clubs, a bocce court on the waterfront. The emphasis was on making Bucksport a town where people wanted to live not just because there were jobs, but also because it was where good things were happening and good neighbors lived.

But there were still signs of a town in search of its new identity. One man in his 20s told me that there remained a disconnect between what he called “the gravel pit boys”—the ones who ride their trucks to the countryside and go target shooting—and the “Heart & Soul people.” He said they needed to know each other. And with so many action plans to consider, I heard concern that the council would need to find a way to know which ones, or even one, they would move forward on.

Earlier that day, I saw Susan Lessard. She had moved her boat to the Bucksport Marina. She and her husband have put their Belfast home on the market and are going to buy in Bucksport what she called “our forever house.” She said that town planners from all over ask to visit, wanting to see what they can graft onto their own communities. Thinking about Bucksport’s promising future, “I get goose bumps,” she said.

I visited again with Pat and Ed Ranzoni. Pat said she welcomed Whole Oceans and its promise to be an environmental steward. But her Native American roots made her sympathize with the fish. “Will they ever see sunlight?” she asked. It was clear she hopes a few will find a way to escape to the sea.

As I write this, I’m hearing that the Maine Maritime Academy will likely buy a slice of the mill site to create a safety and offshore survival institute. The expectation is that several thousand young mariners will stay in town while they study, letting Bucksport reclaim a part of its past as a place where great ships left for foreign seas. There is hope that some of these mariners will even return to live here one day. I also hear about the prospect of a new inn for those travelers who start turning left at the stoplight.

I learn that the Whole Oceans groundbreaking is planned for the end of this year, or soon after. The skeleton of the mill will be replaced by a gleaming indoor fishery on the spit of land known as Salmon Point to the ancient peoples who gathered there. After the plant is built, the eggs will arrive late in 2019. The first salmon will leave two years later. The first 10 years’ worth of adult salmon have already been presold. Initial plans are to employ 50 workers, and when production grows, so too will the workforce. Piasio says 100, 200, or even more will be needed in the years ahead. The world wants salmon, and America produces only 5 percent of the demand. The sky, I am told, is the limit.

When I reach the mill, I turn back along the river toward town. I think of the town planners who come here to learn how to turn hardship into hope. I wonder if some things, like the relentless character of people who show up in the winter dark at a paper mill for more than 80 years, belong solely to this place, and cannot be explained with a to-do list. Time and again I’m told about how competitive you have to be growing up in Bucksport—whether it’s in football, or wrestling, or softball. Even the high school robotics team made nationals in its first year.

Of all the memories I carry of my time here, the strongest is of the walk I took a year earlier along this path to the mill with Danny Wentworth. I had arranged a tour of the mill site with Jeff McGlin, vice-president of AIM, who was managing the demolition, and Danny had asked to come along. This was already the fifth mill McGlin had taken down. He was taken aback a bit when a former papermaker showed up with me, but he opened the car door and Danny climbed in.

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

It was like driving through the wreckage of a bombed-out neighborhood. Danny played tour guide, pointing out where various machines had once been fired up. He was surprised to learn that McGlin had spent more than 20 years working for a Wisconsin paper mill, one that had also been closed. Danny showed emotion once, when we came to the walkway between the parking lot and the gate entrance he had once used every day. Now, weeds had overtaken the landscape. “It used to be so cared for,” he said.

Twice, Danny told McGlin that “a very good source” had informed him there had been two offers to buy the mill and restart it. McGlin said rumors were always part of the business. “So it wasn’t true?” Danny persisted. “No,” replied McGlin. (Danny remains unconvinced on this point. “I know we had offers,” he will tell me later. “I know we could have kept going.”)

Photo Credit : Gabe Souza

As we walked back toward town, Danny shook his head. He had not expected to like the man in charge of tearing down the mill, but he did. “I can’t blame him,” Danny said. “He’s not the enemy. There’s probably a better market for former paper mills than new ones.”

When we parted, he said, “Look around at other places whose mills closed. People are flying out of them. Not here—I’m proud of my town.”

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen