The Maine Peninsulas | A World of Their Own

The wildly beautiful Maine Peninsulas invite ambling and stopping … And returning again and again.

Reid State Park’s distracting beauty encompasses Atlantic views, large dunes,

and miles of sand.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Harpswell Peninsula

Midway down the western side of Harpswell Peninsula, the choppy blue water is spotted with two islands, John and Joe, named for a long-gone shipbuilder’s sons. “I’m not partial, but of all the peninsulas, this is the best,” declares Albert Allen, standing on his family-owned wharf at Lookout Point, where Allen’s Seafood sells fresh lobsters, crabs, and clams, with a side order of impossibly lovely island views, shimmering water, and a picturesque jumble of shacks, barns, bunkers, and traps.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

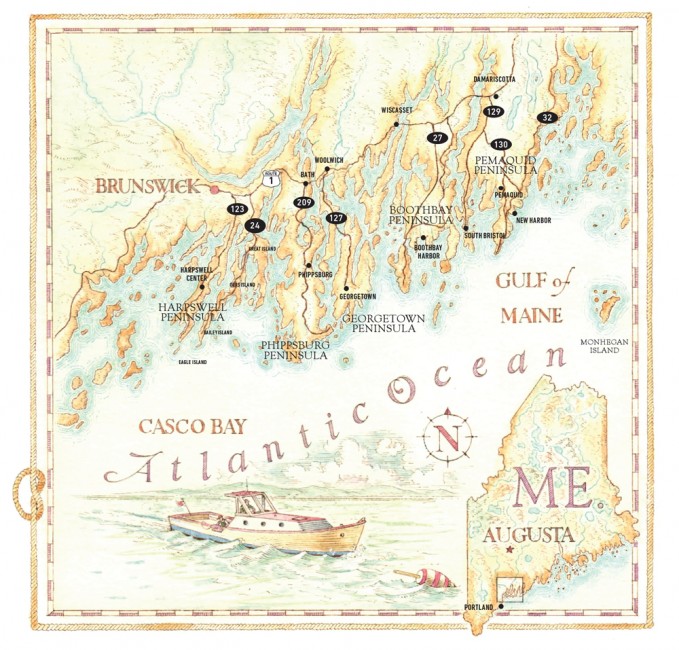

We’re at the start of a five-peninsula-hopping expedition that begins just over a half-hour north of Portland, where a series of tentacles dangles down into Casco Bay. Harpswell, Phippsburg, Georgetown, Boothbay, Pemaquid: names that sound like fingers plucking strings, like wooden ships. We’ve left U.S. Route 1 at our backs, heading south to the fierce Atlantic on our first skinny peninsula. Maybe it’s the nature of peninsulas: Neither mainland nor island, separate yet connected, but already it feels as though we’re adrift in time.

The next days will be the perfect collusion of “ambling” crossed with the notion of “by chance.” If it’s open and looks inviting, we’ll stop. If a road winds seaward, we’ll go down it.

To land’s end and back, over and over and over.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

The Allens built this wharf in 1956, and Albert’s stepdad, Dain, 79, began lobstering here when he was 5. Sporting an Allen’s Seafood cap, he grins, “I’ve done a little bit of everything and haven’t had to work a day yet.” Most mornings he’s here by 5:00 a.m. and out on the water by 7:00, trailed by Mr. Wrinkles, his 10-year-old pug. Neither has any plans to retire.

“I’ve got a perfectly good boat,” Dain says, “and I’m putting together another one over they-ah.” And yes, he talks that way.

Photo Credit : Dave Stevenson

“The man’s never going to give up; he’s a local legend,” Albert says proudly. “His wrists have been broken so many times from working so hard, but he’s rebuilding that boat,” and he nods at the hulk resting nearby on land.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

A breeze blows up the road, pushing us a short distance to The Harpswell Inn, where Dick and Anne Moseley have owned this 1761 landmark for the past 10 years. Anne grew up and has deep roots in Harpswell. “I’m never giving up my point,” she says. (Though the inn is for sale, their “other” house is just across the street.) Breakfast is 8:00 to 9:00, no fooling around, when Anne’s famous blueberry cake will appear.

Meanwhile, there’s supper to be had. Erica’s Seafood, on Basin Point, is near to closing, but the shack’s still hopping when we arrive at 7:00 p.m., blue umbrellas raised over picnic tables and a pier loaded with yellow lobster traps in reach. Rather than rush, we cross the parking lot to the Dolphin Marina & Restaurant’s indoor dining room—same view, related family. “Hope you’re enjoying the sunset,” beams owner Mimi Saxton, as if she cooked it up specially. Light bathes the sailboats in deepening gold; six puffs of juicy local scallops materialize.

Next morning, we’ll return to the marina to catch the Marie L. to Eagle Island, for the short boat ride to Robert E. Peary’s summer home. Buoys flash by, tethered to invisible lobster traps below, and on the horizon the island rounds like a bowler hat. Peary built his house to look like a ship (he was a civil engineer before he became a famous Arctic explorer), and it’s decked out with the fascinating flotsam of an extraordinary life: narwhal tusks that look like unicorn horns; the megaphone that he used to yell at his dogs (in “naughty” Inuit) on nearby Upper Flag Island.

Phippsburg Peninsula

Just past Bath, Route 209 South twists by lobster shacks, aging boats in backyards, and flashes of salt marsh that expand into vast plains, greener than any field. And when the road takes a turn, there’s no major sign, more like a big roadside Post-It, announcing: Popham Beach State Park.

Certainly it’s no preparation for the Saharan plain of sand that shimmers and spreads for three fearless miles. A whistle shrieks and a lifeguard races by, frantically waving at four waders struggling to reach the temptingly nearby island, water swirling around their thighs. Fox Island Closed Due to Incoming Tides reads the sign they apparently ignored in the parking lot. Chastised, all turn back. Chunks of driftwood stumps lie strewn on the beach; the sand seems molded into tiny silent waves.

If you don’t know how to eat a lobster, Spinney’s Restaurant, three miles away in the shadow of Fort Popham, on the banks of the Kennebec River, offers an instruction chart. You can also absorb visual pointers on how to build a spectacular driftwood fence, which is all that separates us from the sand and water. Bathrooms are labeled Buoys and Gulls (“You want the mermaid, hon”); the wood interior is draped with sea paraphernalia; and the haddock chowder is addictively good. Chunks of fish, potatoes, and a reddish tang of paprika: A second cup feels inevitable.

Civil War–era Fort Popham is weird and wonderful, like the bottom half of a more modern-day Colosseum. All archways, tunnels, and half-moon curves, it’s a haunting relic that echoes with children’s shouts and offers shade to fishermen casting their lines. The view across the water to Georgetown foreshadows our next stop, which is another poetic truth of peninsulas: You’re always looking over to the next point of land.

Georgetown Peninsula

Coveside B&B in George-town feels like a secret tucked down a lane, overlooking Sheepscot Bay. Gardens edge the shingled house and cottage that Tom and Carolyn Church have brought back to life; our deck overlooks a verdant lawn sloping to Gotts Cove. In the morning we linger over strawberry shortcake and a mix of scrambled eggs with goat cheese, red fingerling potatoes, bacon, arugula, and nasturtiums. “Less schmoozing, more schlepping, those are my instructions,” Tom says, before setting down the coffeepot and joining the lively talk between tables. “The thing about Maine,” he says, “you begin to let go.”

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Naturally, he has a few suggestions: Five Islands Lobster Co. and Reid State Park, Maine’s first state-owned saltwater beach. “Each of the fingers [peninsulas] has its own personality,” Carolyn observes. “Topographically they may be similar, but Georgetown is the wildest. You couldn’t get here until the early days of the 20th century—it wasn’t served by the bridge.” (Nice, too, that we can see across the water to Southport Island, where Rachel Carson built her summer cottage in 1953 and found inspiration for her environmental classic Silent Spring, and where her ashes are scattered. “Here at last returned to the sea,” reads the bronze marker.)

Reid State Park is the perfect place to walk off breakfast. Distractingly beautiful, its Half Mile Beach is mounded with smooth stones, like slumbering elephants; beach roses crowd the sand; golden tidepools are edged with algae; and Mile Beach curves like a smile. The convergence of colors—sand, sea, stone, and sky—is a palette of perfect paint chips for creating your own oceanfront room. If time seems to slow down on the peninsulas, you could say that it stops on the beaches.

That’s not the only thing that stops. “I can’t feel my legs!” a delighted teen, up to her waist in the sea, announces to her brother. Ethan, a lifeguard who trains at Mile Beach every morning, sometimes in a wetsuit, confirms that today’s late-June water temp is a frosty 50 degrees. (Popham, he says, is warmer.) So is Mile Beach really a mile? It doesn’t look it. “Mile-ish,” he smiles, “but almost two miles with all three beaches combined.”

Post-beach, we succumb to the tiny Post Office Gallery, brimming with the work of four local artists, from wood-fired pottery to landscapes (cards, too). I’m admiring Lea Peterson’s color-splashed portrait of a lobsterman at Five Islands Lobster Co., a lively wharf/eatery where families crowd picnic tables, butter dripping from fingers and chins, celebrating the day’s catch. “He’s over there right now, working on his pots, cleaning them up,” she says of the lobsterman. Small peninsula: Paint or be painted.

Frankly, it would probably be a peninsular crime to slink past Georgetown Pottery, an institution since 1972. The porch groans with pots and bowls, and in the studio, you can watch the artisans at work. Owner Jeff Peters doesn’t look like a ceramics mogul—he’s busy lifting a heavy tray of mugs—but this is the mother lode of pottery. Room after room displays sinks, lamps, clocks, anything that can be rendered in clay. The patterns are pure Maine—blueberries, lighthouses, birches filled with light. It’s the best kind of success story: Guy starts off in a one-room log cabin (sound familiar?) and makes good.

Boothbay Peninsula

Driving feels effortless with 360 degrees of classic scenery. We turn off Route 27 toward Boothbay Harbor, passing Wildcat Creek, patches of woods, and the Boothbay Playhouse, keeping an eye out for glints of water. It’s a busier stretch than anything we’ve seen so far, but a fun contrast. Our room at the Spruce Point Inn overlooks Boothbay’s bluer-than-blue harbor—and it’s Windjammer Days, a full-on celebration of wind, sails, and water, in a town that needs no excuse to celebrate any of the above.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

The inn’s motorboat, helmed by Captain Richard Baines, runs guests into Boothbay Harbor from 10:00 to 6:00. As we skim the water, he points out Ram Island Light, a bald eagle on Mouse Island, and Cuckold’s Lighthouse, a B&B. Among his recommendations? Lobster Dock for lobster rolls, Down East Ice Cream Factory for the cold stuff, and Blue Moon Café for breakfast. It’s morning, so we saunter into Blue Moon. Smells like fresh blueberry muffins. “Fred just made ’em,” the woman behind the counter tells us. She points to a photo on the wall from SKI magazine that reads Fred Munro. “And now you know everything I do,” she adds.

Well, the man of mystery makes a mean breakfast. “This is the best French toast I’ve ever had in my life!” exclaims a customer, polishing off his “Texas Toast,” a delirious mash-up of pecan crisp and French toast. People-watching is in a dead heat with Fred’s food: The café’s deck overlooks Pier 8, hub central for Balmy Days Cruises, Burnt Island Lighthouse Tours, whale watches, and puffin cruises.

You can cross the harbor via the long-est wooden footbridge in the U.S. A charming, wood-shingled house dangles off the bridge, perched on pillars: the 1902 Bridgehouse. A sign on the door says it’s for sale. At that moment, a man sets up a precarious ladder and begins touching up the red window trim. We shout hello, and in short order we’re inside Allan Miller’s shipshape shack, admiring the gleaming wood interior and the Adirondack chairs on the back deck, facing a long view out across the boat-strewn harbor. There’s no quirkier or more inviting waterfront property.

But when we learn that Allan also owns Pepe’s Café, the “oldest eating house” in Key West, it clicks. All the best coastal vacation towns feel like a cross between Provincetown and Key West—a mix of liveliness and looks—and Boothbay Harbor fits the bill. With no shortage of cafés, restaurants, and shops, there’s also enough beauty to stop you cold.

Pemaquid Peninsula

Depending on whom you ask, the Native American word Pemaquid means “situated far out” or “long point.” Either is perfectly suited to Rachel Carson’s peninsula, where the groundbreaking conservationist lived and studied tidepools, and where the Rachel Carson Salt Pond Preserve lives on, just north of New Harbor, on Route 32, on Muscongus Bay.

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Photo Credit : Sara Gray

Of all the peninsulas, Pemaquid is the one that most reminds me of a sailor’s knot. Roads curl and loop around; you may think you’re headed to Pemaquid Harbor, but somehow you wind up in South Bristol. Which, by the way, is a fantastic little harbor town, buoyed by water on both sides of a bridge that’s tight with buildings clinging like barnacles, including Maggie’s Fishmarket and rustic Osier’s Wharf for lobsters, clams, and a crunchy fried-haddock sandwich (“Eat Here or Take Out”).

Turn around and try again, and this time it’s a toss-up which way to go: left to Pemaquid Beach or right to Colonial Pemaquid, with reconstructed Fort William Henry, on a site that saw its first fort built in 1677. A handsome Colonial farm from the 1700s houses the archaeology lab, and a museum displays artifacts dug from the surrounding area, dating to the early 17th century. Paddlers can launch a kayak from the public landing into the Pemaquid River; experienced kayakers can cross John’s Bay and skim past South Bristol’s rock-perched cottages or circle Witch Island, with a chance to spot osprey and seals. Or … turn back and stretch out on Bristol’s long, curving Pemaquid Beach, an expanse of white sand.

But with daylight running out, it’s a straight shot down to iconic Pemaquid Point Light. The blindingly white tower sits high on a bluff that’s 100 percent Maine—sheets of rocky coast below, 180 degrees of pure ocean drama, waves crashing and spray flying. Really, how better to end than on this scenic high note, punctuated by a lighthouse wrapped in coastal beauty? Staring out to sea, I feel something cold nudge my leg: a wet nose, belonging to a black Lab, attached to a twentysomething hiker. “It doesn’t get any better, does it?” he grins.

Maine peninsulas are for savoring, for driving off the map, for returning to. And for always something more to see.Albert Allen claimed his peninsula was the best, and it was … along with the next one, and the next. A collection of dangling fingers, a perfect hand, with so many moments of beauty, so much wild peace, that all definitions of “sleepy” may have to be rewritten.

SEE MORE: Maine Peninsulas | Photographs Guide to the Maine Peninsulas | Where to Play, Eat, Shop, and Stay

Annie Graves

A New Hampshire native, Annie has been a writer and editor for over 25 years, while also composing music and writing young adult novels.

More by Annie Graves