Fighting for Survival | The Plight of Small New England Colleges

When small New England colleges fail, the towns they call home share the pain. But one Maine college has found the way to pass the ultimate test.

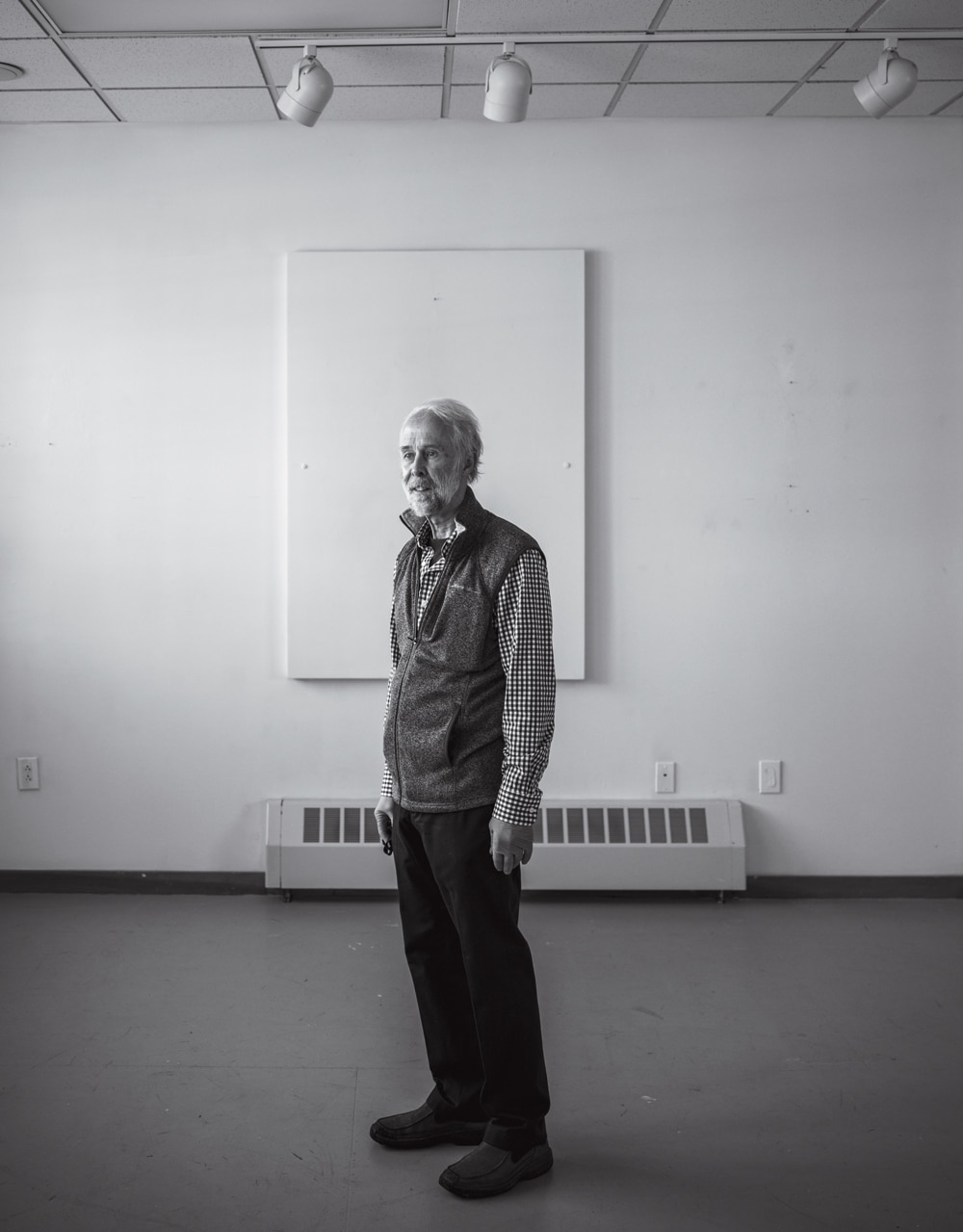

Founded in 1834, Vermont’s Green Mountain College closed last year in the face of declining enrollment and economic pressures, leaving former president Bob Allen to become a tour guide for prospective buyers. Hoping to avoid a similar fate, Maine’s 207-year-old Colby College is making new investments and forging closer ties with the larger community.

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

On sunny days like this, there once were students flipping Frisbees or crossing Granville Street to Main Street for a slice from the Poultney House of Pizza or a beer at Tap’s Tavern. Bob Allen sounds almost as though he can see them as he describes this during a walk across the vacant quad. The last president of this 185-year-old college in Poultney, Vermont, he remained almost alone on the abandoned campus, trying to find a buyer for the 22 tidy red brick buildings before they fall into ruin, to meet what creditors consider Green Mountain’s sole remaining purpose: paying off its $21.5 million worth of debt. In the end, the place was put up for auction.*

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

This will be the second successive fall in which the college won’t be opening its doors to students anticipating their independence and embarking on their higher educations. Green Mountain closed in 2019, after its final crop of graduates crossed the lawn outside the library in their caps and gowns with dandelions tucked behind their ears to symbolize persistence; the yellow weeds, one anthropology professor noted, are resilient and seemingly impossible to kill.

It was a nice thought. But Green Mountain and other small colleges like it, tightly woven into the history and culture of New England as in no other part of the United States, have been uniquely vulnerable to demographics, economics, and technology, among the other changes that have left many fighting for survival—now including a pandemic that is vastly worsening their already grave financial and enrollment troubles.

Theirs is a narrative of anger, worry, and frustration triggered by abrupt misfortune, poor decision-making, and a failure to stay relevant, with the resulting life-changing shock to students and alumni. Maybe there’s a tinge of smugness out there in the rest of society, too, at the spectacle of elitist academics proven to be not as smart as everyone thought.

There’s another side, however. Quietly and without as much attention, some New England institutions have been trying to take hold of their own fates in dramatic new ways that are restoring long-severed connections to their communities, with the added benefit of exposing their students to a world beyond the campus. More will shut down, of course—and at a much more rapid pace beginning this autumn, as the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic increases expenses while driving away desperately needed enrollment and reducing families’ ability to pay. (In the most dramatic example of this, the chancellor who oversees Vermont’s state colleges recommended closing three public campuses because of the financial downturn, though the idea was withdrawn after a public outcry.) The number of institutions at risk of closing in New England in the next six years has nearly doubled since the start of the pandemic, from 13 to 25, according to the Boston-based college advising company Edmit.

Whatever happens, New England will almost certainly see many more of its colleges—which have long been familiar features on the landscape—fail. And while the focus will likely continue to be on such things as the strain on suddenly displaced students, what to do with now-abandoned campuses, and how to settle those accounts, perhaps the greatest long-term casualties will be the ones that get the least attention: the surrounding towns.

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

For that perspective, Jonas Rosenthal picks up on a tour of Main Street in Poultney, one end of which is dominated by the idle college as if a continual reminder of what the locals now are up against. “That was the bank,” says Rosenthal, who was town manager in Poultney for 31 years, tilting his head toward an empty building with grand white columns and a “For Lease” sign in front of it. “They’re moving out too,” he says, gesturing at an insurance agency. A restaurant, a drugstore, and the co-op have all closed.

“There have been a lot of hurt feelings,” says Rebecca Cook, a Poultney native and director of the public library, which sits just a stone’s throw from Green Mountain—where her son was a freshman when it folded.

There were 427 undergraduates at the end, down from nearly twice that many 10 years earlier. Another 150 people worked at the college, which had a payroll of about $6 million—a big loss in this small town of 3,340. They shopped at the supermarket and the hardware store. Median home prices plummeted when many put their houses on the market.

The least apparent contribution of the college was perhaps the most important, however: A lot of Green Mountain students stayed around after they graduated, settling in town and often starting businesses or telecommuting. There won’t be any more of those now to bring their youth and energy to Poultney. And that matters, especially in a region with three states claiming the first-, second-, and third-oldest populations in the nation: Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. One in four Vermonters is 60 or older, which is expected to increase to one in three by 2030.

“There’s an economic impact, but there’s also a very human impact” of suddenly being without a college, Cook says. “So many students and faculty who were involved in things in town are gone.” Since the college closed, “you see the immediate effects, but it’s going to take a while to understand what the long-term effects are going to be.”

Cook pauses. If they ever even thought about it, she reflects, townspeople assumed the college would be there forever. Now, she says, “We could end up with a ghost town.”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

___

Eighteen New England colleges have closed or merged since 2016, and many others are on shaky ground. At least seven made the most recent list of institutions whose cash reserves and other assets are so low they require additional federal oversight. Accreditors for several more have put them on probation.

Vermont alone has seen the shuttering of Green Mountain, the nearby College of St. Joseph, and Southern Vermont and Burlington colleges. Even the public university system has already shrunk from five institutions to four, with the fusion of Johnson and Lyndon state colleges. Its enrollment down to 150 and running regular annual deficits, Marlboro College was scooped up by Emerson College in Boston. The two schools call this an “alliance,” but it resulted in the closing of Marlboro’s campus in Vermont after its final graduation was, in a last indignity, thwarted by the pandemic. Many such combinations are between unequal partners, and they leave the smaller institution essentially reduced to the name of a department or division of the larger one; in this case, Marlboro’s liberal arts and interdisciplinary studies program became the Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies at Emerson College. (The Marlboro property was sold in May to a network of public charter schools with aspirations to start a new college there.)

In Massachusetts, Mount Ida and Newbury colleges have closed, and Wheelock College was combined with Boston University, which took over its valuable real estate and its school of education—renamed, in a similarly symbolic gesture, the BU Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. Pine Manor College was acquired by Boston College. Hampshire College is revamping its educational model to stay relevant after its then-president announced it was the latest New England institution that might have to merge or shut down.

“The amazing thing is that there haven’t been more,” says Thomas Parker, a senior associate at the Institute for Higher Education Policy who taught higher education finance, administration, and history for 15 years at Boston University.

There almost certainly will be. That’s in part because there’s been a huge decline in their biggest pool of customers. Thanks to an anemic birth rate, the supply of 18-year-old high school graduates in the New England states has been steadily declining since its last peak, in 2011.

Demographics are not the only problem for New England’s colleges. High prices have also kept students away. Published tuition and fees at private nonprofit colleges in New England are, on average, 29 percent—and, in Massachusetts, 44 percent—above the national average. That’s partly a function of high energy costs, but in some cases it’s also a legacy of self-importance. After all, doesn’t everybody want to go to college in New England?

Not anymore. The number of freshmen coming here from out of state fell by about 40 percent in 2017, the last year for which the figure is available from the New England Board of Higher Education. And that was before the coronavirus shutdowns made students reconsider going to a college far from home, while also causing deep financial hardship on parents. Meanwhile, the decline in the supply of graduates from high schools in New England shows no signs of slowing. In fact, it is projected to speed up.

Many institutions now are doling out so much money in discounts and financial aid, just to attract business, that their revenues are falling even as their sticker prices climb. By the time Green Mountain closed, federal figures show, not a single student was paying the full tuition.

This is a problem for more than just the students who attend, and people who work at, New England colleges and universities. Higher education has an outsize influence on the economy here. It’s a major employer, purchaser of goods and services, and manager of real estate, and it produces research and graduates that fuel innovation. Although enrollment at New England colleges and universities has slipped below a million, that still has a significant spinoff impact. Nearly one in five students from outside the region who complete a bachelor’s degree were still here a year later, research shows, invigorating their communities.

There’s been little sustained public reaction, however—as seems to follow instantly when factories close or corporate headquarters move—to the existential crisis facing one of the region’s most important industries. Allen and others in Poultney wonder why the state didn’t step in to save Green Mountain, which made a bid to survive by merging with neighboring Castleton State University but was rebuffed.

This lack of response is in part because the scale of the predicament is not well understood. Colleges don’t like to talk about their shaky finances; it’s in their best interest to project a sense of permanence, and to make prospective applicants believe that they’ll be lucky to get in. That has so infuriated unsuspecting students and their families at institutions that abruptly closed, such as Mount Ida, that Massachusetts legislators passed a law requiring new financial disclosures that could expose potentially fatal shortfalls. College closings in New England are becoming so routine, in other words, that lawmakers are attempting to make them more orderly.

But something else is at work, too, in this broader failure of society to actually try to prevent more shutdowns: historic ambivalence in the relationships between these institutions and their surrounding communities, from which many are literally walled off.

“I think some people do” take for granted the importance of the colleges in their New England towns, says Bob Allen, back in Green Mountain’s otherwise deserted administration building. “Some will only acknowledge this when more institutions begin to close.”

Laird Christensen thinks so, too. A member of the faculty at Green Mountain, he has moved from Poultney to Prescott College in Arizona, which has also taken many of the last Green Mountain undergraduates.

A bearded mandolin player and songwriter who was a regular at bluegrass night at Tap’s, Christensen has a simpler way of summing up the situation: by quoting folk singer Joni Mitchell.

“You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone,” he says.

___

The tenor of town-gown relations in New England might best be traced to 1806, when students at Yale and off-duty sailors in New Haven faced off with knives and clubs. In 1841, still other Yalies attacked a firehouse, in revenge for which the townspeople tried to burn down the college. In 1854, locals wheeled two cannons to the campus and were about to fire them when constables intervened.

Today’s divides are less violent but still run deep. They’re largely cultural. Academics often speak the language of a doctoral dissertation, alienating many of their neighbors. And many students aren’t just occasionally unruly; they’re often from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds and hold different political views from those of the people in surrounding towns, especially in rural areas, inviting resentment.

Thomas Parker remembers talking to the Rotary and Kiwanis clubs in Bennington, Vermont, when he was vice president of Bennington College. “They were very interested, in the way an anthropologist might be interested in a primitive tribe,” he says. “There was never any sense that the college was important to the town.” On the other side of the equation, Parker says, “the faculty had a kind of liberal notion that they should be doing something for the town. And they didn’t know quite what to do. The town wasn’t really interested in a free ticket to a modern-dance performance.”

Even in Poultney, where town-gown relations were comparatively peaceful, “there were people of a certain age group who were causing trouble downtown and townspeople thinking they were from the college and that everybody at the college was like that,” says Jaime Lee, a Green Mountain alumna who stayed in Poultney, where she chairs the planning commission and runs a consulting business as a grant writer and digital media producer.

There was a political rift, too: Even in blue Vermont, 45 percent of Poultney voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election versus 49 percent for Hillary Clinton, a much closer outcome than was reflected by the sentiment on the liberal campus. “Green Mountain and the town didn’t coalesce as much as we would like. A lot of the time we were at odds,” says Danny Lang, another Green Mountain graduate who stayed, and who jokes about the college’s emphasis on environmental studies and the environmentally conscious and generally left-wing students it attracted. “You’ve got rural Vermont people versus hippies.”

Nor does higher education today enjoy the veneration that it used to. There have been athletics and sexual abuse scandals, and parents who have used their wealth to shortcut the admissions process. Colleges and universities pay generous salaries to their employees and are tax exempt—some in spite of having huge endowments—which means higher property taxes for their neighbors.

Gallup finds that fewer than half of Americans have a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in higher education, which has suffered the biggest decline by this measure of any institution. And while people feel more positively disposed to their local colleges or universities, a poll by Boston public radio station WGBH found that fewer than half have a positive view of even those.

“Colleges and universities can represent affluence, but sometimes they can also represent arrogance. I get it,” says Gary Stewart, a member of the board of the International Town Gown Association, or ITGA, who deals with this in his role as associate vice president for community relations at Cornell. “There’s just this sort of odd gulf sometimes.”

Colleges and universities are working to reverse this. Forty-four percent team up with their communities on economic development projects, according to the ITGA, and 29 percent are jointly building housing, offices, public transit, and other projects.

Some pitch in voluntarily toward the fire, police, and snow removal services they use, though generally in amounts far lower than their towns and cities ask them to. None of the institutions in Boston pay what the city has requested of them, for example, though they say they offer scholarships, business loans, and other benefits worth at least as much.

“When they’re working well, colleges and universities are letting people know about lectures and music, that there are students who want to volunteer in the community, that there’s the opportunity to take classes,” Stewart says. “Eventually you beat down some of the walls that prevent people from talking to each other. There are more connections than are obvious a lot of times.”

None of those things brought together the people in Poultney with the students at Green Mountain anywhere near as much as what finally united them in common cause, however, Lang says. “Now that the college is not in operation, the town and the students are on the same side,” he says. “They’re all pissed off. People in town were up in arms about the college closing, and so are the students.”

Laird Christensen, whose academic specialty is resilient and sustainable communities, says that for small colleges to survive they must be willing to adapt. “[They] need to be woven into the fabric of the community, so that they become impossible to take for granted.”

___

Construction noise rattles the windows of the many vacant storefronts on Main Street in Waterville, Maine. A new boutique hotel is going up. A block away, a onetime department store is being converted into a $20 million arts center. And in the heart of the downtown, on a former parking lot, a brand-new five-story brick-and-glass building has settled in among the early-20th-century colonial and Renaissance Revival architecture of the once-bustling business district.

“Colby,” it says near the top, in five-foot letters.

This is the anchor of an ambitious attempt by one New England college to help restore the flagging fortunes of its town: a dorm for 200 undergraduates from Colby College who are adding life—and much-needed commerce—to a street where they’ve already helped attract a few new pubs, restaurants, and coffee shops. It’s the other, less widely told story of how some New England colleges are quietly trying to heal their connections to their communities, and help themselves in the process.

Colby is also behind the new hotel, has plans to redevelop the long-empty building across the street that once housed the local hardware store, and is a big investor in the arts center, which will include an offshoot of the college’s art museum along with cinemas, studios, and a connection to the theater next door in City Hall.

Photo Credit : Trent Bell

It even loaned money to an alumnus who redeveloped the abandoned mill where Hathaway shirts were made during Waterville’s manufacturing heyday, which has been converted into apartments and retail businesses including the ultimate symbols of youthful hipness: a microbrewery, a CrossFit gym, and a coworking space. Along with a foundation and some private developers, Colby is seeding projects worth $50 million in all in a downtown where half the businesses had closed.

“None of this would be happening without Colby’s investment,” says Shannon Haines, president and CEO of the arts organization Waterville Creates. Main Street, she says, “was quite empty and depressing and lacked investment for a long time. It wasn’t until Colby came in that things started to change.” That spurred others to step in. “It feels hopeful again,” Haines says. “Everyone’s aspirations have been raised.”

Colby once needed Waterville more than Waterville needed Colby. A prosperous rail hub with paper and textile mills powered by the Kennebec River, Elm City—named for the elegant elm trees that hung above the graceful streets—was booming. Old black-and-white photos in City Hall show a busy Main Street filled with people riding on electric trolleys to and from stylish shops. Boxed in by the railyards and the river, however, Colby had no place to expand. It announced in 1930 that it was moving to Augusta, where a benefactor offered it a larger tract of land. But Waterville residents raised $107,000—$1.6 million in today’s money—to buy Mayflower Hill, a 714-acre wooded idyll at the edge of town on which the college could build a bigger campus.

There it would stay, largely removed from the forces that pushed the city into decline. Unable to compete with cheaper imports, the mills began to close, ending with the Hathaway factory in 2002. A Walmart opened at the highway exit, sucking business from downtown. Other chain discount stores would follow. The clothing shops on Main Street went under. Then the hardware store. Young people left. Even the elm trees died, from the wilt fungus Dutch elm disease.

In the 1999 movie Mystery, Alaska, written by Waterville native David E. Kelley—son of a onetime Colby hockey coach and creator of Chicago Hope, Boston Legal, and Big Little Lies, who still has a summer house near Waterville with his wife, the actress Michelle Pfeiffer—a rural town is facing the threat of a new, thinly disguised big box store called Price World. “Margie has relatives in Waterville, Maine,” one of the characters in the movie warns. “She said as soon as Price World moved in, all the local shops went right out of business.”

“It seemed obvious what we had to do,” says David Greene, the president of Colby. “We owed this to the city.” Besides, he says, “particularly when you live in a fairly small city, your fates are intertwined. If the city is having deep challenges, there’s no doubt that it’s going to affect Colby. If we’re in a place where faculty don’t want to live, staff don’t want to live, we lose the very best people.”

So Colby began investing in the world around it. Unlike many other small New England colleges, it has the resources to do that: an $870 million endowment. Compare that with Green Mountain, whose endowment when it closed was $3.6 million. But even in a city in such obvious need of help, the college’s sudden interest was not universally welcomed. “We’re down here. The college is up there on the hill,” says Mike Roy, longtime city manager, gesturing with his hands.

Roy grew up in Waterville and went to Colby, where he played hockey and remembers being called, disparagingly, a townie. “There certainly was suspicion and just plain opposition because ‘they’re not like us,’” he says of the initial reception to the college’s outreach. “There was that suspicion that Colby is just trying to take over and they’re only doing things to help themselves.” There was skepticism inside Colby, too. “At the beginning I was hearing we should be spending our money on campus, not downtown,” Greene says.

The biggest gesture was the Main Street dorm, whose hallways and public spaces still smell new. The 200 students who live there are required to do community service, but the greatest service to the community is their presence, says Brian Clark, the college’s vice president of planning. “The idea of getting 200 wallets on the street, that was as great of an economic stimulus as you could think of,” Clark says. Colby’s new hotel and the commercial properties it’s redeveloping remain on the tax rolls as wholly owned limited liability companies, which lessened some community resistance.

Before the dorm went up, “we would always talk up Waterville as a college town, but if you walked downtown there was no evidence of it,” says Haines. “Colby was always seen as being removed. Now there’s no question they’re becoming more integrated.”

Young people are returning. Greene personally lobbied a tech company called Collaborative Consulting, since acquired by CGI Group, to open an offshoot in a building Colby owns across the street from the new dorm; the college sweetened the deal by defraying the costs and the company will offer internships and jobs for students and graduates who want to stay in Waterville. Colby is even planting new, disease-resistant elms, Clark says.

“It feels nicer than it did before,” says Bobby McGee, who moved to Waterville from Florida (“People said, ‘Are you crazy?’”) and opened Selah Tea in the space where a drugstore had long since closed. Colby students make up a third of the business in his café, whose savory smells drift onto the resurgent Main Street. Even now, he says, some locals resent the college, “but I tell them, ‘Do you realize without Colby how many people wouldn’t have a job?’”

Home sales in Waterville are up 33 percent, to the highest rate in Maine, says Roy, who calls what’s going on a renaissance. “That’s a very good sign to us that people have decided to move here.” An analysis by economists at Colby finds the city’s population is, in fact, growing slightly, and the housing vacancy rate is lower than the state average. Things still aren’t great; unemployment remains higher than in the rest of the state, as does the proportion of residents on public assistance, and more than half of the students in the public schools are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

But Greene and others say the college’s reconnection with the city is the first step to helping solve these deeper problems.

Higher education “is much more relevant when it’s connected to the world, not disconnected from it,” he says on the genteel, hidden-away campus that remains a stark contrast to the still-gritty downtown. “Many colleges and universities have been insular in their approach to their communities. They could do a lot more, and recognize the role they play that goes beyond economic impact statements and platitudes. I hope we become a model for this.”

For his part, Roy says there’s a much stronger bond now between his hometown and his alma mater. “Each helps to define the other. Colby helps define what Waterville is, and Waterville helps define what Colby is. I’m surprised that more colleges haven’t made as big of an investment in their communities.”

Haines looks at things more simply. “It’s nice to be on the happy side of this story for a change,” she says.

Even before its last commencement, Poultney residents and civic leaders gathered under the championship banners in the high school gym to spitball some creative solutions to the closing of Green Mountain College.

They could expand biking and hiking trails and beef up outdoor recreation as a draw for tourists. They could try to reopen the co-op and lure a coffee shop to bring more foot traffic to Main Street. They could convert the college into an incubation space or satellite location for a research institution or another college, or a culinary school, or a conference space, or a boarding school, or even a casino or a prison.

But what happens to the campus isn’t really up to the town. The college had to sell it to the highest bidder to pay off its creditors. That wasn’t the only bad news. Without the college contributing its water and sewer payments, Rosenthal informed the gathering, everybody else’s rates were likely to go way up. Even if they do take root, few of the options available to the town are likely to return it to its more contented past, says Patty McWilliams, owner of Hermit Hill Books. “How do you replace a college?” she asks, exasperated.

Many of the college’s departing faculty sold her their books before they moved. “It was sad. I’ve lost some good friends and good customers,” McWilliams says, her cat on her lap on a sofa in the cozy shop. Business has fallen. “I just feel the vibrancy going out of the town.”

But there’s also hope. “People really care about what happens,” McWilliams says. “Where I’m seeing a lot of optimism is folks saying it’s OK and we’re going to find another way,” says Cook, the librarian.

Along with other Green Mountain alumni, planning commission chair Lee is determined to stay. She likes a comparison to How the Grinch Stole Christmas, in which the Whos in Whoville make a circle and sing carols, even though their gifts and all the other vestiges of the holiday have been stolen from them. In this analogy, the college is Christmas, Lee says, and “I’m still singing in the street without the Christmas tree.”

Lang is staying, too. He crafts fine wooden furniture at a workshop outside Poultney that’s redolent with varnish, and lives in a house he built himself. “There’s a lot of people who left town because they think the town is going to fall apart,” he says. “We’re looking at it through a very different lens. We’re starting again from scratch.” So many alumni have stuck around, Lang says, “that the people in Poultney are starting to recognize they’re lucky to have these people from Green Mountain.”

There are embryonic efforts to attract more. The nearby Rutland Economic Development Corporation, for example, rushed together a brochure not so subtly titled “We Want You to Stay: A Guide for Recent Grads for Life in Rutland.” But there aren’t any more students graduating from Green Mountain College. And it’s the town that’s facing many of the greatest consequences of its closing, Rosenthal says, just as more New England towns—to their frustration and regret—will likely have to.

“Some people,” he says, looking toward the empty campus at the end of Main Street, “thought that it would last forever.”

*Editors’ note: Green Mountain College was sold at auction in August for $4.55 million. The name of the winning bidder will be familiar to many Vermonters: Raj Bhakta, the ousted founder of WhistlePig Whiskey and a former contestant on The Apprentice, who recently launched his own Bhakta Farms company. Of his plans for the campus, Bhakta was quoted as saying, “We’re going to do great things in Poultney and Vermont and in America, and we’ll have more to say later.” To learn more about Bhakta’s history in Vermont, check out Yankee’s2017 profile, “The Education of Raj Bhakta.”