Bud Thompson | The Man Who Loved Shakers

For the sisters of Canterbury Shaker Village, their way of life seemed nearly at its end—until a singing cowboy named Bud Thompson came along.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanEditor’s note: Shortly after the September/October issue of Yankee went to press, we were saddened to learn that Charles “Bud” Thompson, whose legacy is celebrated in “The Man Who Loved Shakers,” passed away on August 12, 2021, at the age of 99. A memorial service will be held on September 25, 2021, at the Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum, which he created, in Warner, New Hampshire.

——

The summer that Bud Thompson met the Shaker sisters he was young and they were old.

There were then, in the mid-1950s, 14 Shaker sisters living at Canterbury in New Hampshire. The last brother had died in 1939. There had always been more Shaker women than men, all the way back to 1747, when the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing was founded in England and later brought to America by Mother Ann Lee. Their enemies had named them Shakers or “Shaking Quakers” for their ecstatic worship, for trembling and throwing themselves about and speaking in tongues. Those days were more than a century gone. The Shakers Bud met were a quiet, pious, dedicated lot, their lives shaped by thousands of days of work and devotion into a work of art itself. The Canterbury sisters were living in the twilight of the Shaker utopia.

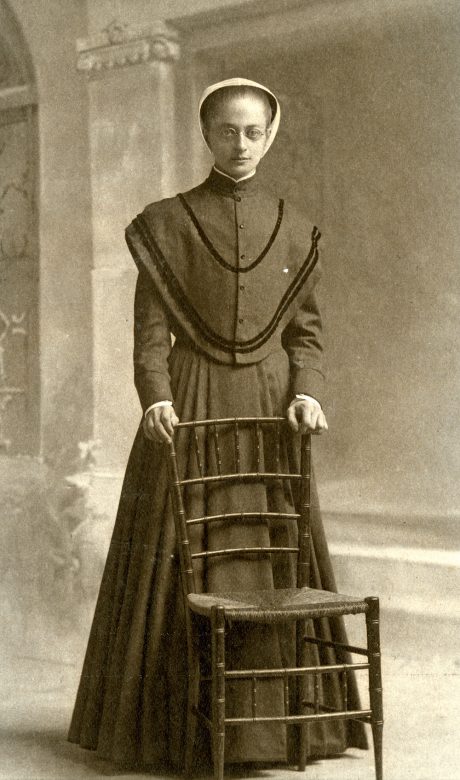

Bud was 33 years old, a big strapping guy with a broad smile and lively blue eyes. He was a traveling troubadour knocking around the West, booked into schools by an agent back east. Before that, at age 16, he was a singing cowboy with his own radio show, 15 minutes a week on WMEX in Boston. He may have been the only teenage singing cowboy from Rhode Island in the whole curious history of singing cowboys.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village

He visited the three remaining Shaker villages at Canterbury; Sabbathday Lake, Maine; and Hancock, Massachusetts. At their peak in the mid-19th century there had been 19 Shaker communities and perhaps as many as 6,000 Shakers. Bud was looking for new folk songs, and his booking agent told him the Shakers had written or adopted some 10,000 songs. The songs weren’t written, the Shakers said; they were received.

His Canterbury visit changed his life and the lives of the Shaker sisters. Walking around the village, he met Sister Lillian Phelps. Lillian came to Canterbury at age 16 sick with tuberculosis. The sisters nursed her back to health. Lillian played the organ every Sunday for the sisters and she gave music lessons. She offered to play for Bud.

“They had this lovely Hook and Hastings organ” in the chapel, Bud recalled. Lillian played “Méditation” from Thaïs—“did a beautiful job”—and two or three other pieces. Then Lillian, who had “a little bit of teasing way about her,” said, “‘Now wait, Bud. We talked. We played a few things for you, and now we’re expecting you to do something for us.’

“I said, ‘I don’t have my guitar. I don’t have any music.’

“‘Now you’re not getting away with anything,’ Lillian said. She was full of fun. She was a serious and smart lady, but she also had that kind of light. She lifts up the piano seat and she pulls out some schmaltzy thing like The Bells of St. Mary’s. So she played the accompaniment as I sang. We became instantaneous friends.”

Music had shaped Bud his whole life. Music led him to the Shakers and to his two wives. His first wife, Harriett, was an organist and choir director at a church, and his second, Nancy, was a soloist at another church. He fell in love with her when he heard her sing.

Bud left to sing in small-town schools on a route that took him through the Midwest and on to Oklahoma. But each Monday he’d get letters from Sister Lillian or Sister Bertha Lindsay waiting for him in Rolla, Kansas (population 464), Hurley, Missouri (population 117), and all the other spots on the map where at the end of the day he knew no one. Bud had given them his schedule before he left. He saved the letters in a big photo album.

This is the kind of devotion that happens in first love, with teens writing letters that cross towns, the country, the seas. But this was the romance of an aging, celibate Christian order and a young man who sang cowboy songs and folk ballads.

The sisters were at loose ends. With the death of their last brother in 1939 they had lost a powerful dynamic. They believed that God was male and female, that men and women, each working in their own sphere, were equal. And they were short of labor. They could no longer run their farm. For that they had to rely on hired hands. They turned to fancy work, to sewing and selling baked goods. If the Shakers’ work was participating in God’s creation, what happened when their work no longer sustained a self-reliant community?

Bud even won the measured approval of Eldress Emma B. King, whose stern manner had left her to be called, out of her hearing, Emma be King. She was in charge of the hardest decisions of their declining years, including closing other villages and the religion itself to new converts. As they closed buildings and villages, she had to weigh many requests by those looking to carry off a piece of Shaker heritage. The sisters were often asked to sell their furniture, tools, music, and historical documents.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village

Eldress Emma wrote to Bud, delivering her verdict, “I believe you are trying to do good in the world and are sincere in your efforts so it is a pleasure to encourage an honest seeker after truth and a high standard of living.” Implied in her judgment were the others she had sent away—or maybe in a Christian way, hosted, fed, and sent away. But the sisters loved Bud from the first.

“He hung the moon in their eyes,” June Sprigg told me. Sprigg spent two summers at Canterbury during her college years and later became a Shaker museum curator and the author of many books about the Shakers. “They saw him as a son. I think he could do no wrong in their eyes. He was just utterly devoted to them.”

They asked Bud to come work for them. He had no idea that he’d be there for the next 31 years.

Eldress Emma was right: Bud was a seeker, but one with a touch of Barnum. He was a showman and a salesman, and that mix would come to their rescue.

He was a high school dropout whose education never ended; he was determined in everything he did. He had become a singing cowboy on a bet. He’d picked up his friend’s guitar and plunked away on it. His friends said: You’re pretty good; you should be on the radio. Maybe I’ll try that, said Bud. They bet $25 that he couldn’t do it in six months. Bud auditioned at radio stations, his older sister Margaretta helping look up stories of the old West to tell. He landed gigs all around Boston.

“I was curious about everything. I still have my ear to the ground,” he told me at his home in Warner, New Hampshire, a week before his 97th birthday. Bud was a seeker, but never a convert. “I’ve had a guiding power, a guiding spirit,” Bud said at lunch one day with his wife, Nancy, and his son, Darryl.

“We’re a religious family,” said Darryl, who was one of the last children to grow up at Canterbury. “We feel that God has led us. I mean that humbly—that God has opened doors for us.”

“So many things have dropped in just at the time I needed them. The right things came. I have to believe it’s more than just luck,” said Bud.\

Photo Credit : Peter Bloch/Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village

Since their earliest days, the Shakers had invited the World’s People—as non-Shakers were called—to witness their worship services. The sisters welcomed everyone who found their way to their hill in Canterbury, a small town 14 miles north of the state capital, Concord. Canterbury Shaker Village was 29 buildings on a hill, mostly wooden, mostly painted white, lined up neatly with rows of old maples and white fences. It was pleasing, the buildings—large and small houses and barns—set out as a child might, lacking the usual configuration of buildings facing a street or a parking lot. In this setting visitors found harmony, serenity, simplicity, solace for the soul. That’s what they told the sisters over and over. They found virtue; they found belief, even if they themselves were not believers. And the sisters took delight in the World’s People, and they charmed many of their visitors.

In their last decades, they didn’t play the part of the pious Shakers. They did sing Shaker songs, but they surprised people with their sense of humor and TV watching—Sister Gertrude Soule loved watching Wall Street Week best of all because Louis Rukeyser was “so handsome.” Sister Ethel Hudson liked watching General Hospital until “all the nurses started getting pregnant.”

There were, by the 1950s, more buildings than sisters. At the village’s peak in the 1840s there had been 260 Shakers living and working in more than 100 dwelling houses, barns, workshops, farm buildings, and nine water-powered mills running on an extensive system of seven ponds and dams. On 3,000 acres they grew apples and peaches, made maple syrup and candy, and ran a productive dairy in New Hampshire’s largest barn. They sewed distinctive women’s cloaks; made wooden pails, boxes, and baskets; sold packaged seeds; ran a print shop; and patented a steam-powered washing machine. Their neighbors may have been puzzled by, or even hostile to, their faith, but they respected the Shakers’ prosperity. As their population shrank they took down buildings and sold land until they had about two dozen buildings and hundreds of acres in hay fields, orchards, and woods.

The Shakers had a wild beginning. In England, the woman who was to become Mother Ann Lee joined a small group of renegade Quakers who regarded themselves as the only true believers. They would charge into churches to disrupt services. They repeatedly spent time in jail. Mother Ann, with seven others, arrived in America in 1774 on the eve of the Revolution. Being English, they were suspected of being spies and spent more time in jail.

Mother Ann’s Shakers are not the Shakers we know. They are not the pious, well-ordered, “hands to work, hearts to God” industrious makers of spare, beautiful chairs, songs, and art. The Believers are spirit-drunk; they speak in tongues, dance and shout, make so much joyful noise unto the Lord that their church services are “a perfect bedlam.”

Ann and her small band travelled through Massachusetts and Connecticut seeking converts. They were attacked, clubbed, caned, whipped, thrown from bridges. In Petersham, Massachusetts, Ann was dragged down stairs “feet first” and thrown into a sleigh like “the dead carcass of a beast,” fracturing her skull, an injury which may have led to her untimely death a year later at age 48.

After Ann’s death, Father John Meacham established the leadership of elders, eldresses, deacons, deaconesses, and trustees. He set up communal villages and formalized the three key tenets of Shaker belief: celibacy, communal life, and confessing your sins. Order was now the face of Shakerism. But the spirit life broke out once more in the 1830s.

Spirits directed the Shakers to create holy feast grounds and to take up holy names for their villages. Canterbury was Holy Ground, and nearby Enfield was Chosen Vale, and so the map of America was populated with the holy: Holy Land, Holy Mount, Holy Grove, Lovely Vineyard, Pleasant Garden, City of Love, City of Peace, Vale of Peace, Wisdom’s Valley, Wisdom’s Paradise.

The Shakers no longer shook and trembled, but they still “lived life on the boundary between this world and the next,” said Shaker scholar Priscilla J. Brewer. Another monastic, Thomas Merton, knew that boundary. Merton had visited the Shaker village not far from his own Kentucky monastery. He wrote, “The peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is due to the fact that it was made by someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it.”

The Shaker sisters Bud knew stood at another boundary: They were almost all orphans. The sisters’ lives as Shakers began with a death in the family. They were passed from hand to hand until they arrived under the Shakers’ care. One of the sisters who Bud knew best, Eldress Bertha Lindsay, arrived at Canterbury in 1905 on a stagecoach. Her parents had died within a month of each other. Her older sister, headed west to get married, left Bertha, almost 8, in Canterbury.

“I will never forget my first day,” she said. “My sister, Mae, left me here with tears streaming down my face. Then Sister Helena Sarle came along and said, ‘Don’t cry, little girl. I’ll be your sister.’ And she was a sister to me as long as she lived.”

The next Sunday was Apple Blossom Sunday in Canterbury Village. “Everyone was singing and marching and they swept me right along to the apple orchards where they gave praise and thanks to God. Birds were singing, the trees were filled with apple blossoms. I began feeling the love and warmth of the people here. This has been my home ever since.”

“That’s the best thing the Shakers ever did, was raise all those kids who fell through the cracks,” said June Sprigg. “That’s better than any round barn or oval box. They provided homes for kids, and most of them left over time. It was a very generous thing to do. I’m a stepmother and I think about Bertha raising these girls and then having them leave and not come back and not live there. She was very brave. There’s a lot of courage in that.”

Alberta MacMillan Kirkpatrick was the last girl raised by the Canterbury sisters. By age 11 she had lived in six different foster families. “I was very upset,” Alberta recalled. “I had considered suicide.”

The day Alberta arrived in 1929 she was scared. “I remember sitting in the parlor at the office and they had called Sister Marguerite and I saw her come running from the Dwelling House. And it was wintertime, December 29, so she had her heavy wool cape on, was holding her bonnet. I could see the cape fly in the wind. That’s how fast she was running down and I thought to myself how disappointed she’s going to be when she gets here and sees me. She’s not going to like me. When she got into the door she fell right down on her knees and put her arms out to me and said, ‘Darling, I thought you would never arrive.’ It was very emotional for both of us…. She was the first person who hugged me since my mother died when I was 6.… She made me into somebody entirely different than the little girl that arrived here. There wasn’t anything I wouldn’t have done for that woman. I adored her.”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village

Alberta grew up, and at 18 she wanted to go out into the world. “It was a very sad thing leaving Sister Marguerite. She had always called me Birdie—she never called me by my first name. And she said, ‘Birdie, it’s your time now to fly…. There’s no life here for you. If you stayed your life would be taking care of older sisters and sick people. And I don’t think that’s what a young girl should face.’”

The sisters had adopted Bud and he had adopted them. Late in life they faced losing their home again. Eldress Emma was prepared to close the village; she was selling furniture. (She’d knock on the door to tell a sister to empty out her desk. It was sold.)

Bud thought Canterbury could become a museum, but one that was more than they could imagine. The entire village, and the old orchards and hay fields and ponds, would be an “open-air museum.” Bud had to show them; he had to sell them on his idea, and here’s where they were fortunate that this “honest seeker” was also a salesman who knew how to put on a good show.

He took his allies, Sisters Lillian, Bertha, and Marguerite, on field trips to Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, and Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Canterbury could be like those museums, collections of old buildings and tools with guides who were sometimes in costume, except that those museums had been assembled with buildings from many places and the guides were dressed up to portray the past. Canterbury was in place, and there were even a few living Shakers who could play themselves—but there would be no dress-up. The Shaker costume was a religious habit. They wouldn’t have their villages turned into a masquerade.

The sisters liked Bud’s idea, and they eventually won over several other sisters, but they had to convince Eldress Emma and then have all the sisters agree. Lillian, the first Shaker Bud had met, had a keen understanding of strategy.

“Don’t call everyone to a meeting in a room and present the idea to them as a group,” she told Bud. “If one person speaks against it, the others will be reluctant to speak for it. Instead, present the idea to each sister individually. Discuss it with each, ask for the thoughts of each, and refine your ideas to incorporate as many of their suggestions as possible. Build consensus and a community of support. Then, you can present the idea to Eldress Emma.”

Lillian told him how. “I will arrange for [Sister] Aida to go to Eldress Emma’s office and express her full support for the project. Then I will contrive to meet Eldress Emma on the walkway as she crosses over to the Dwelling House and I will say, ‘Eldress Emma, did you hear about Bud’s wonderful idea?’ Later in the day I’ll arrange for [Sister] Ida to visit Eldress Emma and give her full backing.”

Emma agreed to the museum—temporarily—until the village was sold to a religious or charitable group, and the last sisters were in a nursing home. In some ways the change to a museum was a new “gathering into order,” the next generation of the Shakers’ idea. Bud set up a museum in the Meetinghouse and they opened a few buildings. He had been collecting Shaker furniture and tools for years. When visitors began arriving, Bertha and later Gertrude welcomed them—they were “guests, never tourists”—and sent them out with Bud. “I’d finish taking a few people around, and a few more, and a few more, and I’d be worn out,” Bud recalled. “Then I’d get a call from Lillian and she’d say, ‘Oh, Bud there’s the most lovely people here.’” And around Bud would go again. The first year as a museum in 1960, 500 guests dropped in for a visit. The young museum was amateur in the best sense of the definition: “something done for the love of it.”

The World’s People came first a few dozen at a time, then 50 to 100 on a summer’s day, and then 40,000 and 75,000 in a season. Some were surprised to be greeted by a living Shaker. Mostly it was all they could do to keep from saying, but-we-thought-you-were-all-dead.

Bertha and Gertrude looked like grandmothers from another century. People saw what they wanted to see in the sisters: living antiques; models of serenity and sanctity in a time of Mutually Assured Destruction. Constancy. They were formal. They lived their belief, to do good work aiming for perfection, but accepting that they’d fall short. They were sure in their faith even as the Shaker life was fading. They were still Believers, and that’s what they wished people would see.

Eldress Emma B. King died in 1966. With Marguerite and Bertha in charge, the museum would be permanent. It was formally incorporated in 1969. Bud was no longer the only tour guide, but he trained everyone. It was his tour. Bud always focused on the positive. The Shakers were unique, benevolent, and charitable. We can learn from them and try to be better people. “What is Canterbury Shaker Village?” asked one newspaper advertisement. “Bud Thompson’s Spirited Tours.”

The Canterbury sisters had left the young museum a puzzle: How do you make a museum about faith? At each stop on the tour, in each building, Bud had a showpiece, something that would grab the attention of even the husbands trailing along at the back of the group. He’d show them the Shakers’ cleverness—the tilting feet on chairs, a long-handled broom to sweep the ceilings of barns, the clothes-drying racks that rolled out of the wall. Then they came forward to talk to Bud as they walked along. “By the time I got done the guy would be all turned on,” Bud said.

This was a show he also took on the road, lecturing about “The Friendly Shakers,” as the promotional flyer said. (“DO YOU KNOW that the Shakers … were the FIRST people in this country to raise, package, and sell Garden Seeds and Medicinal Herbs … were the ONLY successful communal organization in America.”) Sometimes he would bring the sisters with him. “It was a lovefest,” recalled June Sprigg.

If the tour guides strayed too far from “Bud’s tour,” as it was known, they might get the “cookie talk.” Bud would say, let’s you and me go have a cookie. He’d tell them that there were too many facts in their talks and not enough heart. He wanted visitors to be inspired.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village

“People come here to get away from the world and to escape their problems, and we want to leave them with a good feeling,” Renee Fox recalled of Bud’s cookie talk. Renee had started at Canterbury with a summer job in the gift shop more than 30 years ago and was a tour guide before becoming the museum’s archivist. Bud “definitely kept an eye on us,” she said.

Bud didn’t talk about the early radical days of Mother Ann and the later spirit fever. He avoided anything that was messy. Guides were frequently asked about the Shakers’ celibacy. “So if someone asked, ‘Well, did the Shakers ever run away and get married?’ And if you said, ‘Well, yes, they did,’ and then came up with some examples, I mean, that wasn’t part of Bud’s tour,” said Renee. “If someone asked him one of those difficult questions, he would say, ‘I’m interested that you’re interested in that question.’” He didn’t answer; he put it back on the visitor. “Bud didn’t want us to go in that direction,” said Renee. “Bertha used to say how she was witnessing for the Shakers who had gone before. Bud was witnessing to the existence of this community and the things they had done, rescuing them from what could be oblivion.”

“He saw in the Shakers this wonderful potential of the human spirit,” said another former tour guide, Brad Fletcher. “It was very idealistic. People going to the village and on the tour reacted in ways that [showed] this was far more than just visiting a historical site. There was something authentically spiritual about the place, and that is Bud’s gift.”

Bud can be impatient with anything he sees as criticizing the Shakers. One day he said to me, “So there’s the guy Darryl told me about, just coming out with a new book. And I think he made the criticism that I was too idealistic. Well, all I knew was what I knew. I knew them and lived with them—he didn’t. By and large I never worked for people that to me were more what I think Christianity ought to be—not what it is, but what it ought to be.”

Bud ended his evening tours by taking out his guitar and singing “Simple Gifts” and other songs at the candlelit Meetinghouse. He’d then tell a story from Robert Louis Stevenson’s boyhood. Stevenson was very sick; he spent months in bed looking out at the streets of Edinburgh watching “people coming, people going. Everybody busy. The sounds of horses’ hooves and wagon wheels rumbling over the cobblestone streets …. He said that as twilight came, from out of the night came an insignificant little man. Insignificant even by daylight, let alone by night. He was the old lamplighter of Edinburgh whose job it was to light the lamps along the street. But he said wherever this man stopped to light his lamp he left a beautiful, glowing lamp.

“It kind of reminds me a little of the Shaker story,” Bud would say. “Because when the Shaker people started out they were considered an insignificant little group. People didn’t pay much attention to them. Some of the more sophisticated people described them as just a candle in the sun. Not very important. They went about living their life quietly. There was a period when people looked and said, ‘Oh they’re dying out. They were good people, kind people. Too bad.’ And then students and scholars took a second look and they jumped back in utter amazement at what this little group of people had achieved. Insignificant, perhaps, but like the old lamplighter of Edinburgh, what a lovely light. Their membership started decreasing. They’re almost gone. But you know what? There’s never been a time that the light has shone brighter. There’s never been a time when more people have come to listen to their words and find out who they are. People are amazed at what this group has done. I think they let us see that people don’t have to live by greed and aggression.”

He closed the evening by leading everyone in singing “Edelweiss,” because he had taken the sisters to see The Sound of Music and all the way home they had sung “that lovely melody.”

“It was romantic,” said Renee Fox, recalling songs rolling out into the night. It was stirring. She doesn’t remember anything else about that tour, but she remembers that. A romantic evening, the starlight, the crickets, the mist coming off the hills, moving through the orchard and Bud singing. People didn’t forget it. Maybe they couldn’t have told you anything about the Shakers’ travails, or explain what they believed about Christ’s second coming, but they knew the Shakers were special people.

The Shakers, by the 1970s, were like a national pet. They were seen as a living museum of old-time American values of hard work. There were lavish books, museum exhibits, documentaries. Shaker furniture was bringing astounding prices. Celebrities were bidding serious money to collect simplicity and grace. To the World’s People in the late 20th century, the Shaker religion was an American edition of a Vermeer painting: a few objects, daylight slanting in the window, stillness, silence, and grace.

“We’re an endangered species, so people like us,” said Sister Gertrude.

The Shakers became a product with Shaker chair kits, all manner of “authentic” Shaker touches like Shaker kitchen cabinet pulls, and “Shaker polo” shirts from Lands’ End. The Shakers were upstaged by their good work, their beautiful furniture and villages, their smart inventions. They were prisoners of their furniture. “I almost expect to be remembered as a chair or a table,” said Eldress Mildred.

By dying off the Shakers had fulfilled the definition of utopia: the good place that is no place.

Photo Credit : Erin Little

In the end, only two sisters lived in the 56 rooms of the large Dwelling House, Sisters Alice Howland and Ethel Hudson with her six-toed cat, Buster. One sister and a longtime resident who had never signed the covenant lived in another large house. The other three sisters—Lillian, Bertha, and Gertrude—lived across the road in the Trustees’ Office. They were too few to pray in the Meetinghouse. Bud drove them to church in Concord.

“We are now just a group of older people trying to care for each other, maintain our homes, doing what good we can and salvage what good we can from Shaker history of the past,” Eldresses Frances Hall and Emma B. King wrote to a reverend in Ohio.

And at the only other surviving village, Sabbathday Lake, Eldress Mildred said, “It is good and therefore of God and no good is ever a failure.”

Carrying a belief across generations is an achievement, a Herculean effort to maintain clarity of purpose and practice amidst the muddle of human emotions. The question isn’t why they died off, but how did they hold it together for so long?

Eldress Lillian Phelps died in 1973, Eldress Gertrude Soule in 1988, Eldress Bertha Lindsay in 1990, and the last, Sister Ethel Hudson, in 1992, and for the first time in 200 years, since they were “gathered into order” at Canterbury, the Believers were gone. A few Shakers remained at Sabbathday Lake, but that part of America that was the City of Peace, the Chosen Vale, Holy Ground, that part of America was no more.

Bud was asked to sing at their funerals, but he couldn’t do it. He had trouble even talking about losing his sisters, decades later. He left Canterbury to found the Mount Kearsage Indian Museum in Warner. He had been collecting Native American baskets and canoes and pottery and clothing his whole life. At age 68, Bud wasn’t too old for new ventures. People around Bud tried to talk him out of it. After all, even established historical museums were struggling to hold the public’s interest. Dartmouth wanted his collection, but Bud refused. He put everything he had into the museum and it took hold. He was celebrated for his tenacity and vision. Two years ago, at age 97, Bud was awarded an honorary high school degree.

Photo Credit : Geoff Forester/Concord Monitor

On the night she died, Bertha wrote her last letter on earth. It was to Bud. It was found at her bedside the next morning. In a shaky hand that fell crookedly across the page, she wrote: “Please dear Bud take time to care for yourself better….You are so dear to me. I wish it possible for me to take away all your worries, but I have you lovingly in the hands of our Father to ask [him to] walk with you, guide you & bless you…. With all my love, Bertha.”

“What were you worried about?” I asked him one afternoon.

“About the village and the end of it. I didn’t want to see that happen. And the worry that I would lose them. It was Darryl and I that spread Bertha’s ashes after she died. It was her request that we do that. She loved Darryl and she loved me.”

On a raw, windy day in March, I was early to meet some people at Canterbury so I walked uphill to the front of the Meetinghouse and stood there looking out at the rolling fields below. I felt reassured standing there. The place hums; it smiles back at you. It’s what the ancient Celtics called a thin place, where heaven and earth are close, a holy place.

Two hundred years of devotion changed this hilltop. But there’s also a lot of hardship in the Shakers’ story. Hiding in there is an unreckoned ratio of suffering to contentment. What does it take to create a few acres of peace? And would we know peace—true peace, not just the walled-off opposite of no war and no hate, but peace—would we know it if we see it? It’s here on this New Hampshire hill. It feels powerful, deep, resonant. No good is ever a failure. That’s what I think about as I drive down the hill, round the corner, and Holy Ground disappears from view.

Adapted from Chasing Eden: A Book of Seekers by Howard Mansfield, due out this October from Bauhan Publishing.

Celebrating the Shaker Legacy

The longest-lived religious communal society in American history, the Shakers at their mid-19th-century height numbered some 4,000 to 5,000 members living in nearly 20 communities from Maine to Indiana. New England was home to roughly half of those settlements, a handful of which have been preserved to this day—including the last active Shaker community in the world. Note: Since some places may still be operating under Covid restrictions, please check in advance before making travel plans. —The Editors

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village: Two members of the Shaker sect still live in this c. 1783 village, which maintains 18 original structures—six of which are open to the public—and offers the largest existing repository of Maine Shaker culture. Sabbathday Lake, ME; maineshakers.com

Canterbury Shaker Village: Guided tours and educational programs tell the stories of more than two centuries of Shaker life on this property, which today invites the exploring of 29 historic buildings on nearly 700 acres. Canterbury, NH; shakers.org

Enfield Shaker Museum: The centerpiece of this handsome village turned museum is the Great Stone Dwelling, the largest-ever Shaker edifice, where you can actually stay overnight in an original Shaker bedroom. Enfield, NH; shakermuseum.org

Hancock Shaker Village: Called “the City of Peace” by the Shakers who once dwelled here, the Hancock settlement today is home to 20 original buildings, a working farm, a scenic walking trail, and a significant cache of Shaker furniture and artifacts. Hancock, MA; hancockshakervillage.org

Wonderful article! I have ordered the book. I’m curious why Watervliet isn’t mentioned? My 5th great-grandmother and two of her grown children were part of that community and they are buried near Mother Ann. My sister and I visited there a few years ago. Now I’m interested in visiting the other Shaker sites.

Unfortunately, not much left of that village. I’ve been there and to the cemetery.

I enjoyed this article about the shakers. I have read just about anything I can get my hands on about them.I can’t help but make a comparison (for lack of a better word)to Catholic priests and nuns..I am very sorry that this valuable and so vey interesting piece of history is almost over.

It was nice to read about the shakers once again. I first heard about them when I took US History in college. Having had my other school years outside the US I was amazed by their commitment to their way of life and worship. Thank you for this piece.