The Promised Land | Blue Star Equiculture Draft Horse Sanctuary

When working draft horses grow old, their future can be bleak – unless they find themselves at a draft horse sanctuary like Blue Star.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

On a late-summer Saturday morning, a truck pulling a silver horse trailer slows to a stop in front of a big red barn in a small Western Massachusetts town. Two men step from the cab and stretch away the miles they’ve just driven from a carriage stable in downtown Philadelphia. They walk to the back of the trailer and swing open the door. Inside, a newly retired carriage horse, Sam—a quiet, 20-year-old, chocolate-colored Belgian cross—shifts his 2,200-pound self. He sniffs the air. He swishes his docked tail. He knows he’s somewhere different. He doesn’t yet know what soon will become very clear: that here he will become part of a herd. Perhaps become part of horse-powered farming, transport, and teaching efforts; maybe even go on to enjoy a perfect match with an adopted family. All are shining alternatives to the more typical fate of aging or ailing draft horses, whose massive size and weight mean more meat on the bone, thus more money for kill buyers who purchase the estimated 180,000 American horses annually auctioned for slaughter. Sam could live another 15 years, maybe more. And he’ll start those next years here, where he’ll be loved and appreciated and safe. Where he will be home.

My childhood bedroom windows looked out onto a green field and a stretch of poplar and oak woods. My dreams looked out onto that same green field, but added a white board fence. Inside the white board fence was a small red barn. And inside the small red barn was my very own palomino pony. I’d dash down the stairs at the back of my family’s duplex, unlatch the gate, tack up, and ride blissfully into the woods, which had grown a network of tree-shaded bridle paths.

For a kid so equine-crazed that until my teens I dressed like Roy Rogers during any moment that didn’t require my parochial-school uniform, waking always was a bit of a disappointment. There was no palomino pony outside my window.

Adulthood is a different story, as that long-ago dream actually has come true. There’s a field, but I have to walk a little farther than my back steps; after only a few minutes’ cycle or cross-country ski, I’m standing there. Inside a white board fence. At a red barn. Next to not a palomino pony but a really big horse. One measuring 6-foot-8—just at the shoulders—and weighing in at 3,000 pounds. He and his fellow herd mates are my neighbors at Blue Star Equiculture, the draft-horse rescue and organic farm in Bondsville, Massachusetts, a village within the town of Palmer.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

Over the past seven years, this 129-acre haven—complete with a circa-1890s barn, 20 box stalls and a run-in, four paddocks, and a trail looping for a mile around the edges of pasture, river, and woods—has taken in or fostered approximately 300 homeless working horses. It’s licensed to care for 32, and vacancies are rare. Between 25 and 30 horses have been adopted out annually, including Daisy, an 18-year-old Belgian mare retired from farm work, and Carter, a 15-year-old Percheron gelding who once pulled carriages in Philadelphia. The team now lives in the Berkshires, on a wooded farm that last logged with horses in the 1940s. Former New York City carriage horse Silver Too arrived at Blue Star just as the original Silver (“Silver One”), an Amish-bred Percheron former farm horse and Philadelphia carriage horse, was adopted by a Maine farmer. A New York City carriage driver came here to test-drive Silver Too and soon was driving his new horse around Central Park.

Eight herd members are “ambassadors”—permanent working residents who lead city parades and country weddings, log, plow, and help tomorrow’s farmers learn the true meaning of “horsepower.” The rest of the able-bodied in the herd await new homes. The elderly or ill are lovingly cared for until the end of their days. Thirty lie buried in a quiet corner of the back field.

—

Greeting me inside the white board fence running along Route 181 is a herd representing all five of the big breeds originally used in war during the Middle Ages. Clydesdales, Belgians, and Percherons are familiar to many, while the Shires, numbering roughly 2,000 worldwide, and Suffolks, with only 1,200 left in North America, actually are endangered. For all, picture one-ton-plus heft, all muscle and might, the kinds of horses you see marching across the pages of history books, pulling wagons full of newcomers, skids piled with logs, plows carving out fields of corn, helping to form our world.

Paddy, a 30-year-old gray Percheron gelding, spent a dozen years as a New York City carriage horse. Lucy, a dun-colored Fjord cross in her early thirties, served on the police force at the University of Massachusetts for a quarter century. Romeo, 29, is a former champion racehorse who then pulled an Amish family’s buggy before completing a decade of carriage work in New York City.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

But others had less-storied careers. Gentle roan Clydesdale mare Luna, 9, was rescued seven years ago from a small enclosure in Central Massachusetts after subsisting on dirt and meager portions of hay. Piper, a 9-year-old gray Percheron mare, was given to the farm in 2010, along with three brothers, by a Maine couple whose lives were derailed by illness. Gulliver, a 30-year-old white Percheron who once worked as mascot for the Entenmann’s pastry company, was found wandering in the Vermont woods.

Also filling the stalls at Blue Star are horses whose keep, an average of $3,000 to $5,000 annually, became financially impossible, or whose extent of care was someone’s sad surprise. Still others were plucked from kill pens. For all, the next step was a clean, wood-chip-lined stall in the big red barn at Blue Star, named for the Hopi Native American prophecy that a blue star heralds the coming of a new world, new beginnings.

—

Back when I was dreaming of a horse outside my window, that barn sheltered a dairy herd. When the farm went on the market in the early 1980s, I remember clearly how the suggested uses, including “condos” and “golf course,” shot into my gut as I imagined the gorgeous span being developed, and my town becoming that much less rural and open.

Then a young couple purchased the farm and began tending a small herd of cattle. A cozy breakfast place was built next door. I prayed that the remainder of the farm would go untouched. Gears indeed were turning in the universe—specifically, six hours south, where Philadelphia carriage driver Pamela Rickenbach was troubled about the retirement options for a mid-twenties Belgian/Morgan gelding with whom she’d worked.

Rickenbach joined fellow teamsters Christina Hansen and Justin Morace in researching farms where large horses could happily live out their years. There had to be a few in a country home to 9.2 million horses, one to two million of which are heavy horses known as “drafts,” a reference to the line of the draft from the harness collar to the implement being hauled. The trio found retirement organizations for sport or companion horses. Few focused on draft horses, and fewer used them for anything other than lawn ornaments, or mascots to protest animals working for humans.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

“Being a carriage driver and tour guide in Philadelphia were some of my happiest years,” Rickenbach tells me while leaning against the white board fence and watching the larger horses head into the pasture. “I fell in love with this country, and I fell more in love with horses. We had to come up with something for the horses, and for the world that could benefit from learning about them and with them.”

This 55-year-old native of Manhattan, who grew up in the Andes and the Amazon, had studied horticulture and indigenous cultures before taking the reins of tourist carriages in 2004. Her turf was the pavement; her best instructor that Belgian/Morgan, Bud, who loved nothing more than clip-clopping his passengers past historic landmarks.

In 2009 Rickenbach contacted a former professor about finding land on which to create a horse rescue. She was directed to the Leo S. Walsh Foundation, based in Quogue, New York, and run by Sandy Walsh. She knew of a farm in Western Massa-chusetts, next to the village of Three Rivers, where she’d been raised. Walsh offered to pay the rent if the place could be used as a rescue. Stars—of all colors, including blue—aligned. The owners became the landlords, and Bud became the reason a Blue Star began to shine.

—

The men from the truck lead Sam into the big red barn and the first stall on the right. Nine horses poke their heads from stalls as a young woman directs a hose into buckets of grain. A few stamp their hooves. One lets out a cry of breakfast anticipation. Just outside the door, six hungry horses are tethered to a section of the white board fence. A teenaged boy in T-shirt, shorts, and laced-up work boots sets a rubber bowl of grain on the floor of Sam’s stall. Sam doesn’t seem to know it’s his. The boy stoops to point. “It’s all yours,” he tells Sam. “All yours.”

—

Six-foot-two and slender, with a year-round tan and straight brown hair usually braided, Rickenbach dresses in jeans and T-shirts most days, and is never without shoulder-brushing earrings bearing an equine image, shells, feathers, or a combination of all of them. She is at once a warrior for horses and for the Earth; an adoption counselor; a deft fund-raiser; an expert on horses and history; a businesswoman juggling phone, laptop, social-media accounts, checkbook. Blue Star’s monthly bills total some $20,000. Beyond the Leo Walsh rent payment, much of the rest is up to donors, including 250 “herd members” who pledge to donate at least $10 monthly.

Well-known author and journalist Jon Katz, a newer friend of the farm, in the past year has focused many of his online columns on Blue Star and has established crowdfunding efforts for expenses, including the care of a new Blue Star charge who is nearly blind. The money arrives. Not always in a timely fashion, but it gets there. And sometimes what’s needed costs nothing; it may be as simple as time spent.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

Rickenbach brings an eight-foot ladder over to Tex and braids his mane. At 20 hands (six-foot-eight at the shoulders), Tex has been measured by Guinness World Records as one of the world’s five largest horses. He still easily can pull some 9,000 pounds: three times his body weight. “He’s still in the prime of his life, too, a youngster at 12,” Rickenbach notes. “He came to us with a lot of anxiety from an obvious accident he was in. He has scars on his eyes and one of the pectoral muscles in his chest is severed.”

Tex was given two years to rest before Rickenbach decided to put him into harness last year, and the time off helped. His enthusiastic work has included pulling an oak tree from the river last summer, and he goes into fifth gear as a saddle horse when equipment manager Brian Jerome gallops him over the fields.

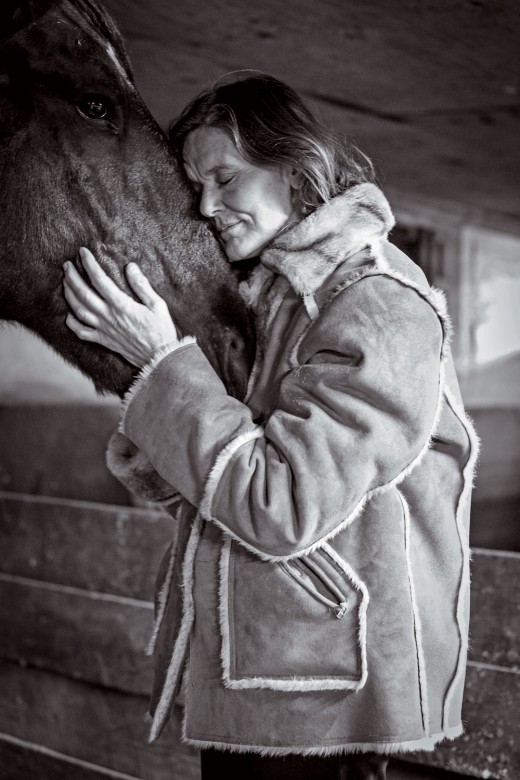

In the feed room at the end of the aisle, Rickenbach measures dinner portions of grain and supplements into the horses’ feed bowls. I stand with local teens and regular volunteers Brandon Carney, Jaci Olson, Josie Desroches, and Gabe Toelken to dole out the bowls. Mucking is done, the manure now heaped in hills of what will become the farm’s best-selling compost. Jerome will start the tractor so that two round bales of hay can be fetched from down the lane behind the barn. It’s body-testing farmwork, the kind I’ve learned can replace any gym. Like the gym, the work is there every morning and evening of the year, in all weather. Unlike at the gym, the smells here can enrapture: the sweetness of the grain, the endless field that a pitchforkful of hay brings to mind, the feel of snow approaching in the cold damp, and, yes, the manure. This from someone who can’t leave the farm without sticking her face deep into a horse’s neck and just breathing in whatever mysterious thing has always drawn me to this animal.

I’m not the only one lost in the experience. “Literally thousands of volunteers have come and helped, and the beauty of all that is that all these people have been given the opportunity to connect with these horses,” Rickenbach says. “But probably one in a hundred actually stay on to help long-term. It’s not for everyone.”

—

The gate is held open as Sam is walked into a paddock that’s a salad bar of green. Just as he begins to nibble near the fencing separating him from five nearby horses who stand watching, gigantic Tex rushes forward, then stops short. Sam doesn’t startle, just moves away with a wave of his tail as Tex takes a few steps along the fence before pawing the ground, making clear who’s in charge.

This is a new herd for Sam, with a new hierarchy to match. But for now, there’s the security of a fence, and the enthusiastic trailing of someone who’s appeared at his back hooves: Three-year-old Sonny, who came to the farm as a starving colt, stands eager. Ears up. Ready to meet someone new.

—

“I always loved horses,” Rickenbach says as she microwaves a plate of leftover chicken and rice for a late supper at the farmhouse’s kitchen table, which also holds a bunch of bananas, an apple pie, a bridle, and a stack of books, including a text on horse-powered farming. “From when I was just a baby, I would arrange grass and little toy horses and build stables in the yard. The other day I looked at this farm and said, ‘That’s why I was doing that back then. I’m actually doing what my spirit is here to do.’”

She’s doing that with horses who are here to work, too. They’re bred for work. It’s good for their spirit, and for their very lives: Muscles kept in good condition mean that a horse who has fallen or is sleeping will be able to stand. Herd members who can work are used in driving and horsemanship lessons, for carriage rides, and for working the organic vegetable and flower gardens that greet visitors to the fields out back. On a given day, a team of Shires might be tacked up to pull a carriage at a wedding, a funeral, or a festival. Carriages and wagons pass my house on test drives, or simply en route to the Dunkin’ Donuts drive-through. Since 2010, in the state’s first official certification program for draft-horse care and use, Blue Star teams have been helping UMass/Amherst students learn a horse-powered way of life.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

If Blue Star is healing and helpful for equines, it’s nothing but the same for humans, who bear their own share of change, age, and issues. Whether military veterans, kids with special needs, retirees, or anyone craving an hour in the open air, just being at Blue Star is an incomparable balm.

Last year, the farm was essential medicine when Blue Star lost a vital member of its human herd. Mainer Paul Moshimer first visited the farm in 2010 and soon was an integral part. A former fire chief and emergency medical technician, an artist and writer, he became the farm’s hardworking operations manager. He and Rickenbach were the heart of the place for the five years until Moshimer’s sudden death in May 2015. Every chance she gets, Rickenbach rides Piper, trying her best to fit in this pleasant therapy before the demands of the day arrive.

Photo Credit : Cheryle St. Onge

Rickenbach acknowledges what Piper and the rest of the herd do for her soul and her journey through grief, but clarifies the balance. “It’s not so much that horses need us. We need them more,” she says as she sits on the grassy slope behind the farmhouse, stripes of pink and blue coloring the sunset. “There’s nothing wrong with them. We’re the ones who are disconnected and fried. They’re the ones who can restore our natural connection to the Earth, and from there we can begin to grow roots again.”

—

Sam is back inside for the night, looking out the barn door again. It’s easy to imagine that he’s also looking back on a day that began with that long road trip and arrival—not to mention working the chain on his stall until he managed to unclasp it and wander over to the white board fence. There were horses to meet. People to meet. Countless pats and comments about his Mohawk-style mane. There were two apples in his dinner grain, two buckets of water, fresh and cool hanging nearby. Now there’s a bed of clean shavings beneath his hooves, a pile of fresh hay in the stall corner. There’s a teen who’s closing everything up for the night. Hollywood casting couldn’t have done better on this day when a draft horse who needed a home landed at one so fitting and hopeful, for both humans and equines. “Good night, Sam,” says the girl, whose first name, not unlike Blue Star itself, is Destiny.

For more on Blue Star, go to: equiculture.org.

What a fantastic article!! I have met Pam and been to Blue Star! It’s a world all it’s own..never want to leave!

I am a proud supporter of this wonderful organization that takes in retired, neglected and surrendered work horses and I believe in their mission. So much so that I am part of “the Herd”. I joined because my sister, Miki, who died in 2012 from cancer was an animal lover and rode horses when she was a teenager. I loved to go and watch her ride and jump in the ring. I know if she was still here, she would be a supporter too.

I have been to Blue Star and met the incredible Pam, whose huge heart and hard work have sustained this wonderful farm. She is one of the most spiritual people I have ever met. I am involved in the care of one of her adopted out horses, Rooney, and he is a joy to have in my life. These horses deserve our love and care so much. May God continue to bless all the hard workers at Blue Star, and may we all come to love and appreciate horses, and all animals.

I met Pamela and rode Pipers at the Bedlam Farm Open House in Cambridge, NY last year. I am also a member of the herd. I have tremendous respect for Blue Star and the work that it does. I am a member of an organization, Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, that rescues retired racehorses and gives them a future as well. When I walk into that red barn all my cares and worries wash away.

Wonderful article that gives depth and character. You have to visit Blue Star you will likely find your soul there.

Beautiful photographs and subjects. Thank you!

The spirit of Cleveland Amory is shining down on Suzanne,Pam and all like souls

I read this story when it was published last year in Yankee Magazine and as soon as it popped up in my email from Yankee, I had to read it again, tears in my eyes thinking about the horses that are still sold for slaughter and grateful for Blue Star and Pamela and crew who not only rescue these horses but give them a purpose as well. I live in Aroostook County in Maine, so I am too far to volunteer, but will be glad to help financially, I do volunteer for the Ark Animal Sanctuary here locally and was a volunteer for 20 yrs for the Houlton Humane Society. I too used to dream of having my own horse, wished for one each year on my birthday, unfortunately it was not to be, but we did have cows & chickens for our own milk and eggs. I would love at 62 yrs of age to have a small farm where I could do that and more again. I would take this place any day over any vacation in the city. Thank you Pam for living your dream and creating a life for these beautiful animals.

Living in HI this was a great person and group of young to rread about. New England still there! Mahalo