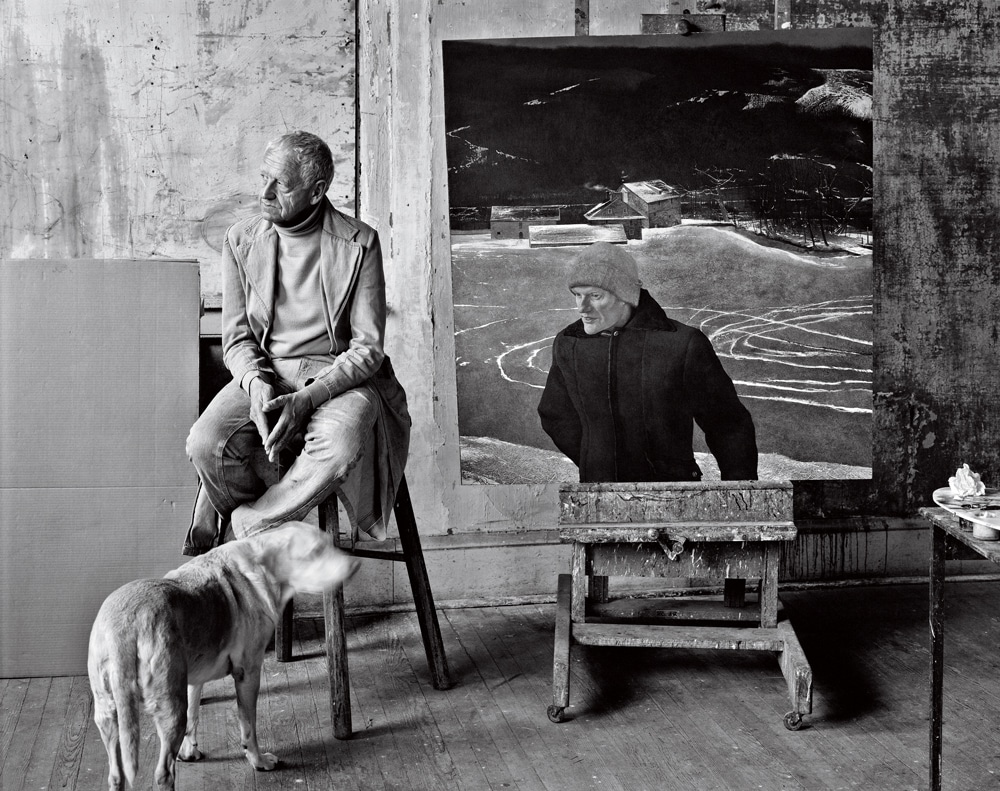

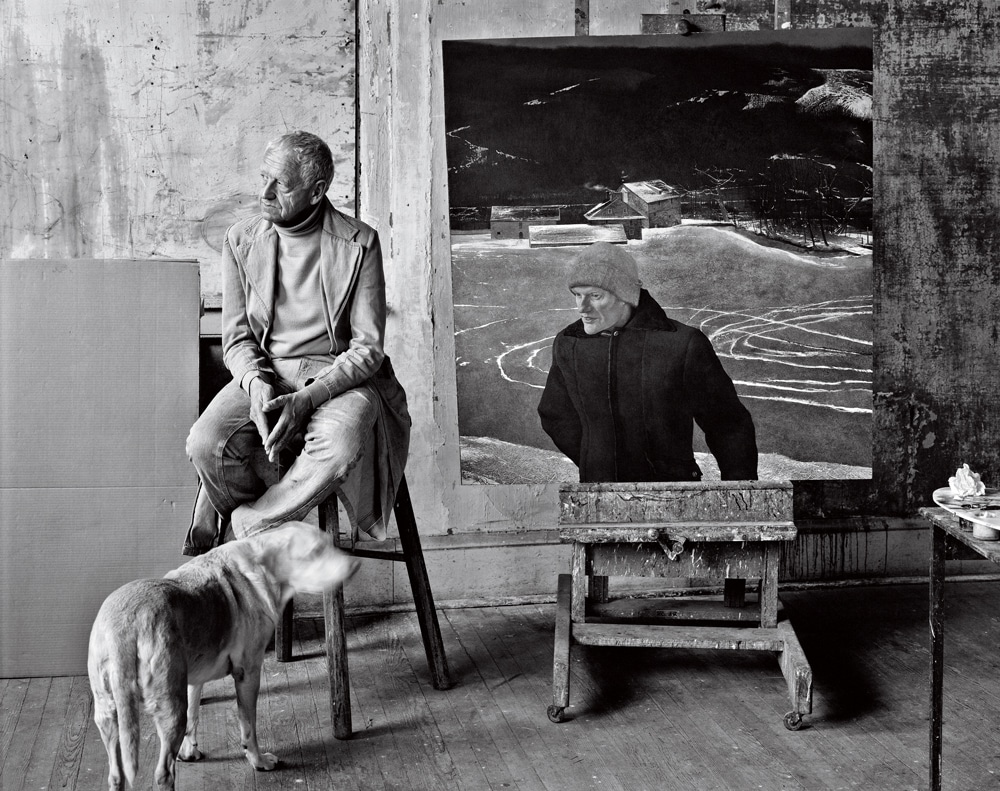

‘Wyeth World’ | First Light

On the centennial of the birth of Andrew Wyeth, a fellow artist and lifelong friend offers this one-of-a-kind remembrance.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

In 1957 my parents bought a house in then-unfashionable Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and Andrew and Betsy Wyeth bought the rest of that old Quaker mill property the next year. As a little boy I had free run of their place and the islands they owned in the Brandywine River, but it was the slow accretion of the many, many lessons and kindnesses they bestowed upon me over the years that shaped my life’s trajectory. Even when I was a child, they exposed me to the creative life in a way that was to fully inform my own.

I recall the day my education began. I was 11, and Andy and Betsy were in their great room. Andy told me to “have a good look” at the paintings hung there. Then he sprang The Game on me for the first time.

“Peter, the house is on fire … you can only save one painting on the way out. Which one?”

I was surprised, but thought it fun and quickly pointed to a work titled Young Bull.

“Good,” said Andy. “Now tell me why you chose that one.”

God knows exactly what I said, probably something vague about liking it the most of all the paintings in the room.

“OK,” said Andy, “but tell me why you like it.”

I ventured something to the effect of liking how the young bull’s coat and the wall and the hill beyond all seemed kind of the same.

Andy’s eyes narrowed until he was squinting, almost glaring, at me. He was standing close to me and he suddenly looked very fierce.

“Peter,” he said, “that’s good, but I mean I want you to really tell me WHY you like this one.” There were only three of us in the room plus their dog, Rattler. The fire in the hearth was lit, but I flushed from something besides the heat.

He pressed for “deeper”—and I cannot at all remember what else I had to say. This went on for what in my recollection seems an eternity, although I’m sure that it could not have lasted more than a minute or two, if that.

Andy was pushing me hard and he wouldn’t let up. I had no clue what was really going on, yet I felt dizzy and excited all at the same time. Then, it was over, and I recollect nothing else from the day. That was when I first had my awareness deliberately challenged to go beneath the obvious surface.

By the late ’60s the Wyeths would see me respond to the heady call of that era, traveling around the country with my camera and my curiosity. When, after a few photojournalistic years, I decided to base my work out of Chadds Ford, Andy and Betsy took me in hand again, and my education resumed at an even deeper level, although I was not always fully aware of the depth of their extraordinary mentoring.

Andy asked me to photograph his paintings with a big-view camera—yet another gift, one designed to instill in me a more reflective way of looking at the world. Perhaps the greatest encouragement that the Wyeths gave me was the idea that you could succeed in life by being curious and expressive. They also taught me about being disciplined in the business side of things. I will never forget the moment in my early twenties when Andy snapped at me, his eyes flaming, “Fuck being a starving artist.”

They brought me as a young adult much more deeply into their wondrous strange world—and what a unique world it was. Andy’s stories told of a fantastical childhood as the youngest and most precocious of N.C. Wyeth’s five children. His youth was a mélange of boundless fantasy and strict technical training. From within the firm grip of his father’s tutelage and influence, Andy learned that he could create and control his own reality, and that early independence played a huge role in how he would live the rest of his life. The Wyeth household was awash in imagination: the swashbuckling tales that N.C. illustrated, the lead soldiers that Andy constantly directed in epic struggles, the elaborately costumed scenes that Andy and his playmates would enact, the heady swirl of famous actors and writers who came to visit.

With his prodigal talent and early commitment as an artist, Andy was able to fashion a life that was entirely of his own creation. And he was blessed to meet and marry Betsy, a woman who could more than hold her own with him.

Thus, “Wyeth World” was, to all of us who orbited around its gravitational pull, wholly unlike conventional society. In fact, among insiders it has often been compared to life in a European court, a life unto itself, with a sense that the “real” world was generally to be kept at bay.

I had my own world, with all of its predictable ups and downs, but whenever I reentered the rarefied atmosphere of Wyeth World, everything felt and looked different. Inside that world we were all the “toy soldiers,” or characters in a lifelong play concocted, choreographed, and directed by the couple on the throne. Life there was layered, with every detail precisely considered and wrought, very much like one of Andy’s great, meticulously controlled temperas. There was frequent drama, but the center always held.

Though their encouragement and generosity were altogether intentional, Andy and Betsy were also tough. The family has a history of being unsparing with candor and criticism, and I learned even as I witnessed it directed at all of us. They did not suffer fools lightly, but as instinctive mentors they made sure that no lessons were lost on me or on others for whom they cared. They knew full well that you have to care about someone to be honest enough to hurt them—that which hurts, instructs.

Wyeth World was high Shakespearean, inked in nothing less than brilliance and steely determination to create and achieve strictly by Andy and Betsy’s own court rules. Banishment was not unknown, and I have seen people of considerable power reduced to tears by suddenly finding themselves on the outside. Life inside, however, was exhilarating and challenging, fun and edgy, loving but demanding, and it held me in full sway, providing a remarkable alternative perspective—or lens—through which I will always behold the larger world.

In 1978, the Wyeths invited me to spend the summer in Maine with them. Driving around with Andy and boating with Betsy, I was meeting the people and seeing the places I had vicariously known for years through his paintings. They gave me Maine, the gift of my lifetime, and it was here that I settled for good. They forever changed my life with Maine, as they absolutely knew would happen.

Photo Credit : Peter Ralston

In 1983, a few friends and I conceived of an organization we would call the Island Institute, and we went to the Wyeths with our draft business plan. They reviewed it, and in response to the part in which we outlined the need to publish something about our intended work and programs, their emphatic advice was: “Do not just offer mimeographed self-congratulatory crap like everybody else does! Go for real excellence, make it the best possible piece ever published about the islands and their people. Make it beautiful, combine stories and art and science, and make people yearn to get the next copy.” Thus was born Island Journal, the Island Institute’s award-winning annual publication, somewhere in format between a coffee table book and a magazine.

Encouraged by their advice, we bet two-thirds of our first year’s operating budget on production of the Journal. It was an immediate hit as well as a considerable factor in the rapid success of the institute. We had taken a chance, pursued excellence, gone far beyond what other organizations were doing, and it was a triumph—all a direct result of the Wyeth modus operandi. I dedicated much of the next 30 years of my life to the institute … seldom far from the Wyeths and their Maine islands.

Andy and Betsy’s lifetime of lessons for me was all about maintaining one’s own high standards and never compromising. They never, ever said as much, but they lived their lives passionately, and by osmosis that informs my life—and the lives of all those they touched—to this day.

And I now play The Game with my family and with special friends. “Which of my photographs would you grab on the way out my door?” I ask. And when they reply and think they have played it well, I come back: “Why?”

The major retrospective “Andrew Wyeth at 100” is on display at the Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, ME, through December. For more information, go to farnsworthmuseum.org.