Magazine

The Long-Dead Native Language Wopânâak is Revived

The long-dead Native language Wopânâak that once greeted the Pilgrims is today again being spoken.

Photo Credit : Kozowyk, Jonathan

Kuweeqâhsun … This was the first word that Jessie Little Doe Baird spoke to her daughter, Mae, the day she was born. The birth hadn’t gone as planned. Jessie had spent most of the last four months of her pregnancy in bed. She was 40 years old and already had four grown children, but Mae was no accident. Jessie took this last risky plunge into motherhood with her eyes wide open.

On July 4, 2004, her home was full of guests. Not only was it Independence Day, but the annual three-day Mashpee Wampanoag powwow was also going on, and Jessie’s relatives were suitably boisterous. “I just went downstairs to tell them to shut up when I started bleeding,” she recalls.

Jessie was rushed to the hospital for an emergency caesarean. Mae was born fine and healthy, but her mother’s bleeding wouldn’t stop. Jessie lost consciousness. In her dreams, she saw herself die on the table–and things easily could have gone that way. But Jessie held on. She knew she had work left to do.

Jessie believes that in 1993 she was given a special task by her ancestors. She experienced a series of dreams in which they spoke to her in a language she didn’t understand: Wopânâak, the ancient language of her people, which had died out sometime in the mid-1800s. She took it as a sign. A Wampanoag prophecy spoke of a time when their language would leave them, only to return when the people were ready. Jessie believed that her dreams were a message from her ancestors, telling her it was time.

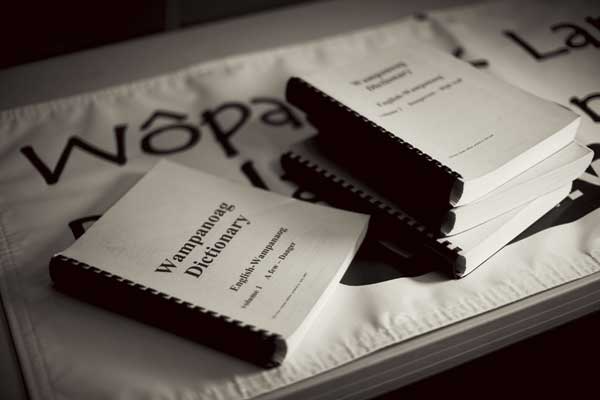

Since then, Jessie has devoted her life to resurrecting Wopânâak, working toward the day when the language that greeted the Pilgrims could once more be spoken aloud in southeastern Massachusetts. Her path has required one leap of faith after another, but she’s had more successes than failures along the way. She’s written a dictionary, gotten a master’s degree in linguistics from MIT, and has even won a MacArthur “genius grant.” But Mae remains her greatest achievement. She was born to be the first.

Before July 4, 2004, there hadn’t been a native speaker of Wopânâak born into the tribe for six generations. Jessie marked the end of that sad legacy with a single word: Kuweeqâhsun … Translated as “good morning,” it literally means “you are in the light.” Jessie always warns that metaphors don’t translate, but it’s impossible not to see optimism in that phrase. On that day, the hopes of an entire people shone down upon one little girl, the seventh generation, wrapped in the arms of her exhausted mother.

—

In a tiny classroom at Boston College, Nitana Hicks waits for an answer. She hasn’t been teaching long, but she’s mastered this skill: staring down her students after a difficult question and willing one of them to answer. She’s had a lot of practice at it. Many of her questions leave her students speechless.

Eventually the silence breaks. A female student volunteers to conjugate the verb on the board. She walks to the front of the class, picks up a marker, and starts writing words that to most anyone outside this classroom seem like complete gibberish.

The consonants and vowels align in ways that defy pronunciation. At least one word ends in the syllable ukw and the numeral 8 is being thrown around as though it’s a letter. (It’s pronounced something like the English oo sound.)

Nitana looks over the work and says, “Close,” then erases an accent from one of the words. The student objects. “I swear to God there’s an accent in the red book,” she says, as she starts flipping through a workbook at her desk.

Nitana looks honestly puzzled for a second, and then, almost questioningly, replies, “I swear to God you’re wrong.”

Some of the other students start weighing in, half on either side. Eventually they figure out that Nitana and her student have different editions. “It’s the updated one,” Nitana says, holding up her workbook. “It should be right-er.”

When Jessie began her work, Wopânâak existed only in written form, preserved on aging documents. Her ancestors were members of one of the first literate Indian nations, owing in part to the colonists’ eagerness to spread the Gospel; the first Bibles published in Boston were in Wopânâak. (Some experts believe the language was Massachusett, which is very closely related to Wopânâak.) The Wampanoag embraced literacy, having learned early on that when doing business with the English it helped to have things in writing. They’d left behind reams of contracts and letters.

When Jessie Little Doe Baird looks back at her early linguistics textbooks, she’s surprised she’s made it this far. “The writing is a little opaque,” she admits. When she began her studies, she was already in her thirties, a working mother with no better understanding of morphology or umlauting effects than the rest of us. “I literally cried reading this,” she recalls. “I thought I’d feel like I’ve been tasked with this as my life’s work, and if this is what I have to deal with, it’s not going to happen.”

But Jessie couldn’t walk away. She enrolled in the graduate linguistics school at MIT, where she began working with Kenneth Hale, Ph.D. Hale was fluent in 50 languages, an expert in indigenous linguistics, and a direct descendant of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. It was that last qualification that got Jessie’s attention.

The Wampanoag prophecy also stated that the children of those who had had a hand in breaking the language cycle would help heal it. That was the moment when the prophecy truly became real for Jessie Little Doe Baird. Any chance of a normal life was gone.

—

The first step in reviving the language was to free those words from the page and put a living breath behind them. Jessie and Dr. Hale scoured the language’s written record. Using related Algonquian languages as a guide, they stitched Wopânâak back together, one word at a time. When Hale passed away in 2001, the language was in good enough shape for Jessie to deliver a eulogy in her ancestors’ tongue. But delivering a speech was one thing; teaching the language to the rest of her nation would prove far more difficult.

The students in Nitana’s class continue to struggle through their lesson, sometimes breaking into laughter over their shared frustration. Wopânâak is not easy to learn. Language is more than just a tool for communication; it’s a philosophy. The way words and thoughts are constructed in Wopânâak is fundamentally different from the way that’s done in English. Take, for instance, the formation of nouns. If an English speaker were to encounter a new animal in the wild, he would likely give it an arbitrary name, like dog or cat or emperor penguin. A Wampanoag, on the other hand, would describe the animal’s key features–its size, its action, and how it moves in relation to other things–and that whole description would become its name. For example, the Wopânâak word for ant comprises individual syllables that convey the following information: It moves about, it does not walk on two legs, and it puts things away. If you were to add another syllable indicating that the animal is large, the word is no longer ant. It’s squirrel.

To make things even more difficult, the Wampanoag were starting from zero. When Jessie and Dr. Hale launched the Wopânâak Language Reclamation Project (WLRP) in 1993, there was no one alive who’d grown up speaking the language; thus, even today, no one is fully fluent. Just as Nitana is teaching this class to beginners, she’s taking lessons from someone further along. All of their teaching tools–workbooks, dictionaries, and curricula–they’ve had to create themselves, revising them as the language comes into better focus.

The process seems impossibly desperate, like renting out the bottom floors of a tower you’re still building–but it’s working. Nitana is the only person in this classroom who’s actually a student at BC. Everyone else has come here after work to slog through conjugation drills and grammar lessons. And they’re not alone. Classes like this have sprung up in various towns on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard as well. One student, Jonathan Perry, drives at least two hours round-trip every week to attend Nitana’s one- to one-and-a-half-hour lesson. When asked why he puts in so much effort to struggle with a language that has less in common with English than it does Klingon, he smiles. “If you want to get an Indian excited about something,” he says, “tell him it’s something that’s just for him.”

—

The first gift we give our children is language. That whispered welcome between a mother and her baby when the child is first laid upon her breast begins a lifelong dialogue through which all subsequent gifts are given. Our beliefs, our dreams, our heritage–we pass these things on through the spoken word. Biology gives us our body, but language delivers our soul.

Before the language died out in the 19th century, Wopânâak was passed down from parent to child for thousands of years. That language cycle formed a link between each new generation and every one that had come before. When they lost their language, the Wampanoag were severed from one of their most basic birthrights. The prospect of winning it back is powerful: powerful enough for Jessie and people like her to devote their lives to it.

The dining room of Jessie’s home in Mashpee is packed with Wopânâak material. Workbooks are spread out on the table and handmade teaching posters are taped to the wall. Jessie is joined there by three women: Nitana Hicks, Tracy Kelley, and Melanie Roderick.

In the next room, Melanie’s son, Muhshunuhkusuw (his name means “he is exceedingly strong”), a toddler, is bouncing off the walls. She occasionally calls out to reprimand him, sometimes in English, sometimes in Wopânâak. She hopes he’ll pick up the language passively and avoid all the bookwork she’s had to do. Asked if it’s hard to raise him in two languages, she just laughs and says, “At this age, you have to tell them everything six times anyway before it sinks in.”

These three young women are Jessie’s apprentices. In 2010 the WLRP received a federal grant that would pay them to learn the language, train as apprentices, and develop early-childhood curricula, with the intention that they’ll go on to teach others. The training is for two years, but it would be a mistake to call it a two-year commitment. “If anyone leaves after two years, we’ll hunt them down and kill them!” Jessie says with a laugh. “We’ll all be with each other, in sickness and in health, for a very long time.”

“As long as we all shall live,” Melanie adds.

The women are chatty and comfortable together, and sometimes the lessons veer off into personal matters. “It gets easier for us everyday to just sit around and talk about everyone else’s business in Wopânâak,” Jessie quips.

There are four major surviving Wampanoag communities in Massachusetts: the two large tribes in Mashpee and Aquinnah, a smaller tribe at Herring Pond, and a band in Assonet. Together they number about 4,000 people. Of the 69 Wampanoag tribes in existence in 1620, today’s Mashpee, Aquinnah, and Herring Pond groups, descended from historic tribes, are still on their original lands, the lands their ancestors settled more than 10,000 years ago, with tribal governments that have never ceased to function; the Assonet are descended from historic tribes that no longer exist as governments. The WLRP is the only project on which all four groups work jointly, because as the United States grew up around them, the Wampanaog largely blended in, and speaking their own language again is about blending in a little less.

Tracy says that as far as she’s concerned, the world is separated into two parts: Cape Cod and “over the bridge.” While she was attending UMass Amherst, she was so determined to return home after graduation that it affected her dating life. “‘Sorry, if you have no passion to stay in Massachusetts, preferably near the bridge, I really can’t,'” she recalls saying.

Becoming apprentices was no idle choice for these women. Jessie regularly refers to the project as “a lifetime’s work,” and the meaning there is literal. These women are expected to contribute to the project, in one way or another, until they simply can’t work anymore.

In the other room, Muhshunuhkusuw loses interest in his toys and comes bounding onto his mother’s lap. Jessie explains that although the apprentices are helping to take some of the teaching burden off her shoulders, the future of Wôpan&aˆak, if it is to have one, must come from their children.

“This is only a means to an end,” she says, gesturing to the materials around her. “The whole purpose of this is to open a Wopânâak immersion school. So by 2015, we’re going to have a school you can take your child to from kindergarten to grade 2. Once schools open, you’re good. You’re golden. That’s where our fluent speakers will be developed.”

The plan is audacious. Jessie’s generation isn’t that interested in being the first to speak the language in 150 years; they’re more interested in being the last not to. Jessie estimates that about 425 tribal members have taken language classes. Some can barely say hello, while others are carrying on entire conversations. Slowly, the language is leaving the classroom. Mothers are speaking it in the home, teaching their children by osmosis. The apprentices chat freely in the language at bars and restaurants. There are even Wopânâak Facebook posts floating around the Internet.

But there remains so much work ahead. Not only do Jessie and her apprentices need to secure a charter for the school, they must write a Wopânâak-language curriculum and train enough adults in the language to serve as teachers. Jessie tries not to get overwhelmed by the enormous size of the task.

“No, I don’t go there. I try not to think about it,” she says. “You know, it will take care of itself.” Pointing to each of her apprentices, she adds, “And if I can’t do it, she’ll be able to do it, or she’ll be able to do it, or she’ll be able to do it. It’s a community effort. You couldn’t do it alone.” She also knows that all they can do is get the language ready and pass it on. What the children choose to do with that gift is up to them.

—

It’s early spring, and the sky over Martha’s Vineyard is a field of unbroken gray. Jason Baird, Jessie’s husband, is taking me on a tour of the tribal land in Aquinnah. We’ve stopped at the Gay Head Cliffs, and we’re walking through a small shantytown of souvenir stands that have been boarded up for the season. Mae follows a few paces behind us. She is a slender 7 years old, with the willowy arms and legs of a dancer. Her puffy pink jacket swallows her whole.

In Wôpan&aˆak, Aquinnah means “the end of the island.” The way the cold Atlantic waters crash at the base of the cliffs, it looks like the end of the world. As far as the U.S. government is concerned, this is all that remains of the Wampanoag nation. Of the four main Wampanoag communities, the Aquinnah are the only tribe with a reservation. It isn’t big–these cliffs, some cranberry bogs, and a few other parcels amounting to no more than 485 acres in all–but it’s theirs.

As we reach the cliff edge, Jason points to the shoreline below. “There used to be a pier out under the tip,” he says. “Until about 10 years ago, you could see the last pylon still sticking up out there at low tide.” He explains that around the turn of the 20th century, tourists would board steamers to come out here and buy trinkets from tribal members.

Jason knows these cliffs. He points out where an ox cart used to run to the shore, and where the army built bunkers during World War II. He talks about how he ran up and down these hills as a child, and how a few months earlier the tribe collected clay here for a pottery class he took Mae to.

“My pot was an indecent-looking teacup,” Mae chimes in.

“Oh, it was a nice pot,” Jason says.

“No it wasn’t,” she shoots back.

It’s hard to imagine now, but there have always been Wampanoag here. Unlike other tribes, these people were never fully forced from their land. After King Philip’s War, 1675-76, their territory shrank to a few small enclaves; the rest of the country has simply grown up around them.

In the language project, the word “birthright” gets tossed around a lot. For many people this concept is vague, but for the Wampanoag it’s as solid as the ground beneath our feet. At the core of Wampanoag society, there is a visceral link between man and earth, as natural as tendon to bone. As long as the Wampanoag stay on their ancestral land, they are linked, spiritually and naturally, to the first ancestors who walked these shores.

“In the philosophy of our people, you’re rooted in the earth just like the plants,” Jason says, “because what comes out of the earth is what sustains you, and when you die, you go back into the earth. That cycle creates this existence where you’ve never been separated. That philosophy is one that we’ve lived with since the beginning of time. When colonization came upon us, there became this idea where you could possibly be severed from that connection. If you’re removed from the chain of life … I can’t even think of a word for it. You’re taken away from everything you’ve ever known … from your existence.”

I wonder how much of this lesson is for my education and how much is for Mae’s. In our mobile age, when success is so often linked to a willingness to move across the country for work or education, a philosophy that preaches staying put is a hard sell. As Mae grows older, she’ll be increasingly exposed to the values of the rest of the nation, and it will be up to her to decide how best to balance the teachings of her parents and the demands of the 21st century.

The three of us reach the crest of a small lookout where the cliffs come into sharp relief against the cloudy sky. Once, clay of every color could be seen in the cliff face, but erosion has dulled it to an earthy, reddish-brown hue. After a heavy storm, trails of color can be seen drifting into the ocean.

Not far from here, beach homes and summer cottages dot scrubby forests. Until the 1960s, the Wampanoag here and in Mashpee had their towns mostly to themselves, running their local governments as extensions of the tribe. But over the past few decades, they’ve become minorities in their own homeland. New developments have blocked off old hunting grounds. And town governments are more often challenging the Wampanoag’s aboriginal right to fish without a license. “We find ourselves in a shrinking territory,” Jason says, “a continually shrinking environment.”

Aquinnah, “the end of the island”: The Wampanoag have been pushed literally to the edge of the map; the language project is a gentle but powerful push back against the tide. It’s something to rally around, a reminder of all they have to fight for and a declaration that they’re not going anywhere. With every new speaker, the roots of their community grow deeper into the soil that has nourished them through the ages.

—

Mae’s version of her birth story is somewhat different from her mother’s: “When I was born, people were so excited they set off fireworks, and now they do it every year.” She tells people this every Fourth of July.

If you frequent the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard, odds are you’ve seen her, folded up on a bench playing games on her mother’s iPhone. She’s clever for her age, perhaps a little mischievous, but there’s nothing to suggest that she was born with a destiny.

Jessie and Jason learned early on that they had to let Mae find her own way with the language. After she was born, they’d tried taking a hard-line approach: For the first four months, she wasn’t exposed to English at all. Jessie remembers this as a difficult time. Even with all her training, speaking Wôpan&aˆak 24 hours a day was something of a strain.

“But it wasn’t as big a problem as it was telling our loved ones basically to ‘shut your mouth,'” she says. Friends and family members, even Mae’s own siblings, were informed that if they couldn’t communicate in Wôpan&aˆak, they couldn’t come over. “‘Sorry, if you’re going to use English around her, then you can’t play with her, you can’t talk to her,'” Jessie recalls telling them. “People were really pissed off.”

Gradually Jessie and Jason realized that what they were doing was counterproductive: A birth that was supposed to rally the community around Wopânâak was instead making people resent it. Mae’s parents realized that if the language were to truly return, it couldn’t be forced on anyone.

The influx of English into Mae’s world proved less disastrous than Jessie and Jason had feared. One day when Mae was a toddler, she looked at her parents and, in the garbled accent of infancy, said the Wopânâak word for “my father”–Daddy, essentially. “I said to Jason, ‘Did she just say what I think she said?'” Jessie remembers. “And he said, ‘I think so.'” Jason tried to play it cool, Jessie says with a bemused touch of jealousy: “I was the one up breastfeeding every two hours!”

Today, when Jessie and Jason speak to Mae, they alternate Wopânâak and English, and they don’t pressure her to respond in one language or the other. When it’s just the three of them, she’ll often use Wopânâak, but in mixed company she always defaults to English. Not long ago, Jessie tried to gauge how much Mae was using Wopânâak outside the house: “I just asked her matter-of-factly one day, ‘Do you use the language with your friends at school?'” Mae replied, “Not anymore.” When Jessie asked why, Mae said, “No one plays with me then.” Mae may have sensed that her words upset her mother, because she immediately went on to tell her that “Jesse” spoke with her in Wopânâak. Jesse was the elderly white man who drove her school bus. Jessie chalked this up as a juvenile white lie.

Not long after, Jessie walked down her long dirt driveway to greet Mae at the bus stop. The door slid open, and the bus driver beamed at her. “Kuweeqâhsun,” he said. He explained that little by little, Mae had been teaching him the basics of Wopânâak on their way to and from school. Hearing her own words come back to her through the lips of a near-stranger was a shock–but also a moment of pride. Mae had taken the language into the private part of her life, the part her parents didn’t oversee.

How Wopânâak will shape Mae’s life is still a question. How much will she use the language as an adult? How many people will there be with whom to speak it? It’s impossible to know, but Jessie has reason to be hopeful. Mae has accepted the gift of her birthright. She can choose to live as a modern Wampanoag and never have to fear that something is being lost in translation.

For more on the Wopânâak Language Reclamation Project, go to: wlrp.org

Justin Shatwell

Justin Shatwell is a longtime contributor to Yankee Magazine whose work explores the unique history, culture, and art that sets New England apart from the rest of the world. His article, The Memory Keeper (March/April 2011 issue), was named a finalist for profile of the year by the City and Regional Magazine Association.

More by Justin Shatwell