The Tinkerer of Dickinson’s Reach

Five wheelbarrows are scattered haphazardly around a large ground-floor workshop in an eccentric, circular building in the woods just a two-minute walk from Maine’s rocky coastline. None of the wheelbarrows looks like the others, and frankly, none looks much like a wheelbarrow. They’re all handmade, four of them by a man named Bill Coperthwaite. (The […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanFive wheelbarrows are scattered haphazardly around a large ground-floor workshop in an eccentric, circular building in the woods just a two-minute walk from Maine’s rocky coastline. None of the wheelbarrows looks like the others, and frankly, none looks much like a wheelbarrow. They’re all handmade, four of them by a man named Bill Coperthwaite. (The fifth was made by a Coperthwaite friend who was inspired by him.)

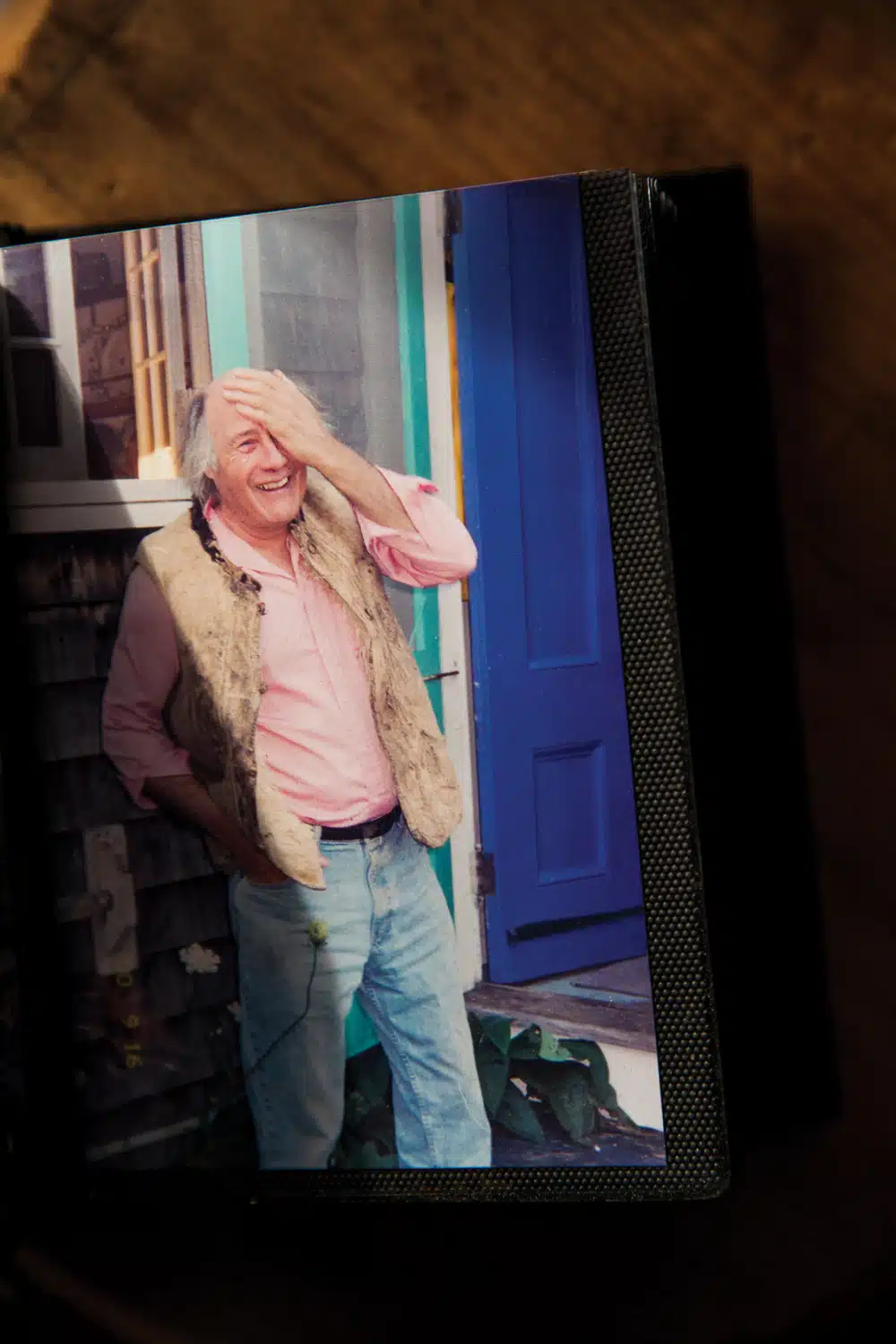

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Most have a single wheel located closer to the rear than usual. One has a pair of wheels that angle inward from the sides, nearly meeting directly under the bed. Coperthwaite was always mystified by the traditional American wheelbarrow—why put a wheel way out front that required you to hoist more weight in the back? It made far more sense to load as much directly over the wheel as possible. So Coperthwaite kept building them, and building them, in search of the ideal wheelbarrow. “These are incredibly maneuverable, and you can walk on the trail at regular walking speed,” said Scott Kessel, a museum designer from Connecticut who was poking around the building with me. “That’s the thing—he was always tinkering.”

His wheelbarrows weren’t theoretical design projects, either. Coperthwaite used them heavily and constantly. He lived at this compound on and off for more than 50 years, amid 550 acres of tangled forest he owned south of Machias. By design, he couldn’t drive to his front door—he’d park near the road and then walk a mile and a half on a narrow footpath, groceries and supplies in tow. (When the tides allowed, he could also canoe about the same distance from a cove across the way.)

Just as his wheelbarrows were ongoing experiments, so too were the structures scattered about the property, which represented an evolution in the type of circular building known as a yurt. Consider the one in which the wheelbarrows are now stored: One of the grandest yurts ever built, it’s four stories tall, with each story partially nested within the next, giving the impression of a backwoods pagoda. The main level is 64 feet across. It has a dirt floor and is lined with stacks of firewood, and along one side there’s a workshop well stocked with wood-carving tools. Upstairs is a kitchen with a woodstove, a library filled with an array of books, settees upholstered with old sweaters, and all of this crowned with a skylighted sleeping space.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

And this is only one of a dozen yurts at Dickinson’s Reach, if you include the outhouses and cooking sheds. (Coperthwaite named the property after Emily Dickinson, one of his favorite poets.) Set amid stately birches and beeches and murmuring white pines, the compound seems as if it were built by elves and gnomes in medieval days. Yet Coperthwaite’s passion was actually not the building of wheelbarrows or yurts. It was encouraging people to live on their own, full of intention, purpose, and simplicity, preferably amid a like-minded community.

Five years ago, Coperthwaite, a complicated man who lived his life with equal parts intensity and purpose, died in a car accident while heading toward a Thanksgiving dinner with friends in Brunswick. He was 83 years old. His sprawling compound was then passed on to five families with instructions to … well, Coperthwaite didn’t leave much of a blueprint. He mostly explained what he didn’t want: a museum, something preserved for future visitors, a place to marvel at what he had wrought. He wanted Dickinson’s Reach kept alive and the community to continue to grow. Somehow.

“He gave us an incredible gift,” said Peter Forbes, a conservation educator and advocate who is one of the original overseers, as well as the author of a 2015 book about Coperthwaite, A Man Apart. “But it’s a huge responsibility too. He wanted his tools used. He didn’t want things numbered and put aside. And he wanted it to change. And that’s a big deal.”

“One of the greatest gifts he gave us was not telling us what to do,” said Julie Henze, another one of the original overseers.

But along the way, the group learned one other thing: The greatest gifts can be the most complicated.

In August 1976, patent no. 3,972,163 was issued to William S. Coperthwaite of Bucks Harbor, Maine. It granted him the intellectual rights to multilevel concentric buildings with rigid walls secured by tension cables. These usually began as a small yurt that would be raised with jacks so another circular structure could be built around it. Then the process was repeated, jacking up the two to build a third structure. And then, sometimes, a fourth.

Coperthwaite’s yurts rarely fail to amaze—for either their simple genius or their offbeat aesthetics—but in truth he was less concerned with appearance than practicality. “Personally, I’m not interested in buildings that you can’t build,” he once wrote. “Our craft world is full of specialists. I’m interested in design that anyone can build and people can gather around.”

Bill Coperthwaite was born in remote Aroostook County, Maine, in 1930, the youngest of four siblings. His family moved to southern Maine when he was young, and he went on to graduate from South Portland High and Bowdoin College. He then attended the influential if short-lived Putney Graduate School of Teacher Education, where he came under the sway of director Morris Mitchell, who himself had been influenced by John Dewey, the progressive educator and philosopher. Mitchell averred that a proper education was best accomplished by doing rather than by note-taking, and all the better if that doing involved social justice and bettering the community.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

From there, Coperthwaite set off on trips around the globe. He was fueled by a curiosity about how native peoples lived and how their cultures were transmitted from one generation to the next. He went to Venezuela to study rural development, then spent two years in northern Scandinavia living with the Lapps. In 1966 he drove from Maine to Alaska to study native crafts and tools, eventually using what he learned to earn a doctorate from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

“That’s what Bill liked to do: to experience things that are really authentic from a deep-seated, deep-rooted tradition,” said Peter Lamb, a former museum director now living in Kittery, Maine, who is another of the original overseers. “He liked being able to see a place before it made a huge shift.”

The outlines of Coperthwaite’s quietly radical life began to come into focus in the early 1960s. With notions of opening his own alternative school, he started acquiring property outside Machiasport in 1960—several hundred acres of cut-over forestland that bordered a tidal pond, for which he paid $3.50 per acre. In 1963 he met Scott and Helen Nearing, who lived a few hours down the coast on the Blue Hill peninsula, and who were pioneers of what was then called the back-to-the-land movement.

Coperthwaite, then 33, took inspiration from the Nearings’ embrace of nonviolence and simple, intentional living. In 1962 he came across a National Geographic article about Mongolia written by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. It featured photographs of yurts, which captivated Coperthwaite with their straightforwardness and the fact that they could be built by those who lived in them. This set him on a quest to adapt the yurt’s basic design for life in northern New England. Instead of using felt, he sided his with locally milled wood. Instead of a single story, he nested them one inside the other. On Google Earth, his largest yurt looks like a bull’s-eye dropped into the Maine woods.

As with so much that Coperthwaite was involved with, his notion of the yurt was never fixed. He was always looking for ways to make them “sturdier, simpler, cheaper, more accessible,” said Forbes. After his first 10 years of building them, he settled into a basic form but continued to tweak the details, like rooflines and interior supports. “To his eye, they would be changing all the time,” Forbes said. At one point Coperthwaite calculated the outward-leaning angle of the walls simply by leaning back in a chair until he felt comfortable, and asking someone to measure that angle. As a result, a built-in bench along a curving wall could become a welcoming place to sit back and read or talk, and eliminate the need for another piece of furniture.

After experimenting with structures on his own land, Coperthwaite brought the idea of the rigid yurt to the world, conducting workshops and offering advice to aspiring builders. He was involved in building an estimated 300 yurts over the years. If you know what a yurt is without resorting to Google, you can thank Bill Coperthwaite.

Yet with all his travels in the United States and abroad, he was always eager to return to his home, where he maintained a rolling stockpile of seven years’ worth of firewood, assuring himself of seasoned wood and comfortable winters amid snow and pines.

While Coperthwaite was a fan of Henry David Thoreau—whose quotes, among others, are tacked up on the walls here and there in his buildings—it wasn’t for the reasons that many have revered the bard of Walden. “Thoreau is an icon of the conservation movement,” Forbes said, “but Bill saw him more for his social justice.” Unlike Thoreau, Coperthwaite did not see untrammeled wilderness as a worthy goal. He was fine with human trammeling, as long as it improved the environment rather than degraded it.

“It wasn’t about ‘leave no trace’ for him,” said Forbes. “It was actually ‘make a trace.’ Make a place beautiful.” Forbes himself had been schooled to think that humans only harmed nature, but Coperthwaite pointed him in another direction: “Bill showed me humans are part of nature and we can create beauty.”

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Forbes noted the path that extended from the main yurt toward the water’s edge. “I never understood completely how this happens, but you can see here just when someone walks on a trail, grass grows and it’s green and it’s a different color than the land that people don’t walk on. It has to do with disturbance. And what Bill taught me is that disturbance can actually create beauty.”

Coperthwaite never fulfilled his early vague plans to establish a school on his land, but he did create what amounts to an informal school. Through word of mouth, people interested in simple living would hear about Coperthwaite and seek him out. (Letters addressed simply to “Bill” and sent to Machiasport invariably managed to reach him.)

“Bill always said, ‘I don’t want to live too close to the road. Too many crazies will come in,’” said Forbes. “But if someone was willing to walk in a mile and a half, he’d at least take the time to say hello to them. And if they stuck around, he’d teach them how to carve a spoon.”

Carving a spoon accomplished several things. Working with their hands allowed Coperthwaite and his visitor to talk more naturally, connecting in ways that sitting and staring at each other across an expanse of a table didn’t offer. It opened the door to talk about beauty and simplicity. “The handcraft was really a way to get at good conversation,” said Peter Lamb.

Over time, those who visited regularly and were most aligned with Coperthwaite’s ideals formed a close-knit circle around him. Many were a generation behind—about the age of his children, had he chosen to sire any. As he reached his 70s, he became more interested in building a lasting community in his forest, and offered parcels of land to his innermost circle if they wanted to build their own yurts. “Every time he came back from a trip, he said, ‘Maybe I’ll see a wisp of smoke,’ suggesting somebody was already there,” said Julie Henze. “The land was important to him, but so was community.”

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Most of his friends already led full lives elsewhere and were unable or unwilling to establish themselves in the woods. Only Peter Forbes and his family took Coperthwaite up on his offer. In 2011, Forbes’s yurt was erected by family and volunteers on a bluff on the far side of the tidal pond, much of it during a summer workshop, near an old spring once dug by early farmers. Coperthwaite set up camp on the site and helped oversee construction.

And so a seed of a community was planted. Yet after the structure went up, Forbes said, Coperthwaite visited only once. “He was constantly talking about community here,” Forbes said, “but there were a lot of tensions in his life. He wanted to be deeply engaged in community, and he couldn’t. He both encouraged me to do the most important things I’ve ever done with my life, and he pushed me away. I think he’s not so unique with that. I think great, great mentors sometimes are like that.”

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

A few years before his car accident, Coperthwaite invited six families to Dickinson’s Reach and asked them to join him by assuming shared ownership of the land. (One felt unable to shoulder the additional responsibility and bowed out.) They formed an LLC such that when Coperthwaite died, the group would assume control of the land.

In some ways, this was simply an update of an old New England way of planning for a certain future with uncertain timing: You take care of me, and I’ll take care of you. “That used to happen with New England town government,” Forbes said. “The town would take care of the people, and after they died the town would get the home. Basically, it’s a very practical thing. But what Bill added was this whole idea of apprenticeship and mentorship. He said, ‘Listen, let’s spend 10 great years together. And we won’t know what will happen after that.’

“And we said, ‘OK.’”

On Memorial Day weekend 2018, I kayaked to Dickinson’s Reach from an adjacent peninsula to visit for two days during the annual retreat, when the families and friends who now oversee the property gather to do work, enjoy long meals together, and talk about what’s next. Of the original five families, only Peter Forbes and his teenage daughter, Wren, and Julie Henze were able to make the trip this year. But they were joined by more than a dozen others, including teens and children who showed a sensible disinterest in the doings of adults and disappeared for lengthy stretches into the woods. The teens knew one another mostly from early-summer visits, and several spent their weekend building an elaborately canopied raft of driftwood and planks. Its inaugural if inauspicious voyage on the tidal pond led to adult discussions on the principles of flotation, the hazards of imperfect balance, and the importance of life jackets. The kids nodded, then disappeared back into the woods.

Shortly before Coperthwaite’s death, the core families realized that keeping his dream alive would require assistance—not only with the work of maintaining the property, but also with giving advice on the future, performing administrative tasks from afar, and spreading the word about the community. So each of the original families invited one other family who had a connection to Coperthwaite to serve as additional pillars of support.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Among those who made the trip this past Memorial Day weekend were Josh and Melanie Wehrwein, who had built their own elaborate three-story yurt near Blue Hill, Maine, where they lived simply and deliberately. (Coperthwaite designed it, although he died before it was built. A friend told Josh that “Bill spent his whole life preparing to design this yurt,” which pleases the Wehrweins.) Kenneth Kortemeier runs a craft school in Midcoast Maine and feels Coperthwaite would be happy that he makes many of the steel tools he uses when teaching wood carving.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

The group gathered near the water’s edge at circular tables outside the cooking yurt. They split into smaller groups and worked on clearing trails, including a new public pathway leading to grassy ledges along the cove. They visited the buildings to assess conditions and discuss work that needed to be done.

Shortly after Coperthwaite died, his community paddled him home across Little Kennebec Bay in a simple spruce coffin, which rested atop poles lashed between two wooden canoes. It was a chilly, bleak November day, and the canoes and paddlers and coffin looked like something from a lost Ingmar Bergman epic. They found Coperthwaite’s yurt just as he’d left it: his desk with piles of letters awaiting responses, books partly read and left open. Here they also found designs for yet another wheelbarrow he planned to make, this one of lightweight Lexan that would be waterproof and shatterproof.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Scott Kessel mentioned that Coperthwaite had asked him recently about the best glues to use on his new wheelbarrow. Others overheard and piped up. “One person was supposed to bring graphite oars for handles, and someone else who was into bicycles was going to bring in a big bicycle wheel,” Kessel said. “And that was his way—crowdsourcing for information.” It would be a wheelbarrow built by a community.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

On Saturday afternoon, the time came for a more formal get-together, so the adults gathered and the kids scattered. About 10 grown-ups—from both the core group and outer circles—headed into the woodshop amid the drawknives and handsaws that had been used to create the small rustic chairs on which most sat. Three quietly carved spoons and ladles as the group talked. No agenda was evident, and at times the gathering had the feel of a Quaker meeting, with silences broken only by the patter of wood shavings falling on the floor.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

Discussions arose about communications among group members and the need for everyone to step up and take on some of the less glorious tasks, like maintaining the website and responding to inquiries. They talked of finding ways to educate the next generation, to make sure they knew that Dickinson’s Reach wasn’t just a playground but also a responsibility—that the kids now tree-climbing and raft-making would eventually help keep the mission alive. A consensus emerged over the hour that the group should take more assertive steps following their five years of mourning Coperthwaite, and position the property for a future beyond them. The year before, they had started an apprenticeship program, allowing one person to stay at the property for six weeks at a stretch, pursuing his or her own projects while helping out with upkeep and greeting the occasional seeker who wandered in. That seemed to be working to return a pulse to the land. Apprentice Leo Stevenson, a philosophy student who had been here much of the spring, was in attendance and reported that he’d spent his time reading, meditating, writing, carving, and taking “long aimless walks.”

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

The group also spoke of their hopes that the apprenticeship might lead them to someone inspired by both the property and Coperthwaite, someone who could help take the compound into its next phase: a retreat, a craft school, a center for intentional living, or something not yet imagined. “You need to have a heartbeat, and feet on the ground,” said Forbes.

Some further discussion ensued—about needed work on trails, about the possibility of building a new yurt for apprentices, about signage and visitors.

“The group has gone from what was to what could be,” said Forbes. A long silence followed. Then Forbes suggested, “Let’s go visit Bill.”

Everyone rose and stretched—Coperthwaite’s handbuilt wooden chairs are simple and inspired but not always conducive to sitting for a long time—and then slowly wandered outside and down a lightly worn path toward a thicket. About a hundred yards in, the group paused amid a stand of thin, leggy maples, then formed a loose circle around a low, long mound with a few struggling blueberry bushes. This was Coperthwaite’s final resting spot; at his request, there’s no marker.

Some heartfelt words were shared about Coperthwaite’s role in shaping their lives. Someone recalled that on his 80th birthday, Coperthwaite scrambled 30 feet up a tree to spend the night in a three-story treehouse he’d built near the water’s edge. “May we all lead lives that when we die we have 40 or 50 friends all over the world who will drop what they’re doing to travel to this remote place,” Forbes said.

Photo Credit : Sarah Rice

At the end of the weekend, all would leave and go back to their lives, save for Stevenson, the apprentice, who would remain another two weeks. To anyone looking around the circle of people—some lost in thought, some smiling—it was evident that Bill Coperthwaite had, in fact, built his community, albeit one less anchored to place than he had envisioned and more widely scattered across Maine, across New England, across the world.

“It’s somehow heartening in this day and age that one man can bring so many people into a remote spot in the woods,” said Forbes. “There’s the magnetic pull of the man.”

I’m 80 with a Brazilian wife, two kids and three grandkids. Feel most at home on a Colorado mountain homestead. Design and build with own hands everything from kitchens, outhouses, I workshops, gazebos and homes for family and friends. Mentored teachers in Colorado and upstate New York independent schools, deaned at Dartmouth, hung out on the shores of Lake Chesuncook in Maine. Love New England. Feel more than a little kinship with Bill—but I’m no blood relation that I know of.

If they need help I will come out from Oregon, just send me a note. Good with tools and people.

Lovely article. I lived in a yert community in the woods at Marry Meeting Farm near Bowdoinham Me. between 1976 and 1978 when I was a student a Bowdoin Collage. There were 9 yerts of various sizes including several large communal yerts, a cooking yert and a sauna yert. Lore had it that Bonnie Raitt and her brother built the community in the early 70’s as a free school. The farm by the road was owned by Priscilla Berry. In those years NY/Maine painter Charles Stanley brought us all together. At one point a self published book I think called Yert Yet was done with creative offerings of all who had lived there. In the spirit of Bill Copperweithe whom I never met I would love to hear from anyone who remembers the community and/or lived there.

Peter I remember you – long dark hair right? I spent a winter at the yurts in 76 or 77, hanging out with Michael – rest his sweet soul in peace. I was working at Stowe house. Something got me remembering that time today, and I looked online see whether any remnant of that community remains, and to try to figure where exactly they were. Such a wonderful part of my live. I loved meditating in the winter silence, and the communal meals and parties at the big yurt. And tromping through the fields to get to the yurts, often in the dark without a flashlight. And of course I also remember Charles, and another guy, Brian I think. I haven’t been to that part of Maine since Michael’s memorial (which was such a moving experience).

Have you seen this interview with David Berry?

https://vimeo.com/386085661

I hope you are well, wherever life has taken you.

Did a workshop with Bill at Mankato State back in the 70’s with a group of teachers from Project Challenge, an adapted Outward Bound program at Green Mountain H.S;, in Chester, Vt. We built a yurt out of miscellaneous materials salvaged there after driving to Mankato in old VW van. Visited Dickinson’s Reach years later and still have plans for three yurts. Farming and gardening in Lubec, just a few miles away. Used experiential approaches in helping folks learn other languages and build community many, many years. Bill’s spirit lives.

Really interresting to look at people and their connections to land and ongoing ideas…the challenges, stewardship, legacy, looking ahead. It’s in the looking ahead that I’m wondering about…how do we keep it ‘alive’ in the same way but with new energy, new ideals? All the issues of ownership, leadership, community rest on keeping it vital–not a museum. And we all can learn from the ethical relationships and bring this to our worlds. Wonderful to think of a place like this as a nucleation point for us all all. Of course I’m an Oregonian so thinking of Oregon Country Fair, and Pacific Yurt Works, and your Oregon kin…Thanks!

Sadly, not long after this article was published Dickinson Reach was vandalized: http://www.thecalaisadvertiser.com/articles/2019/01/23/sheriff%E2%80%99s-office-seeks-vandals-who-ransacked-coperthwaite%E2%80%99s-yurt