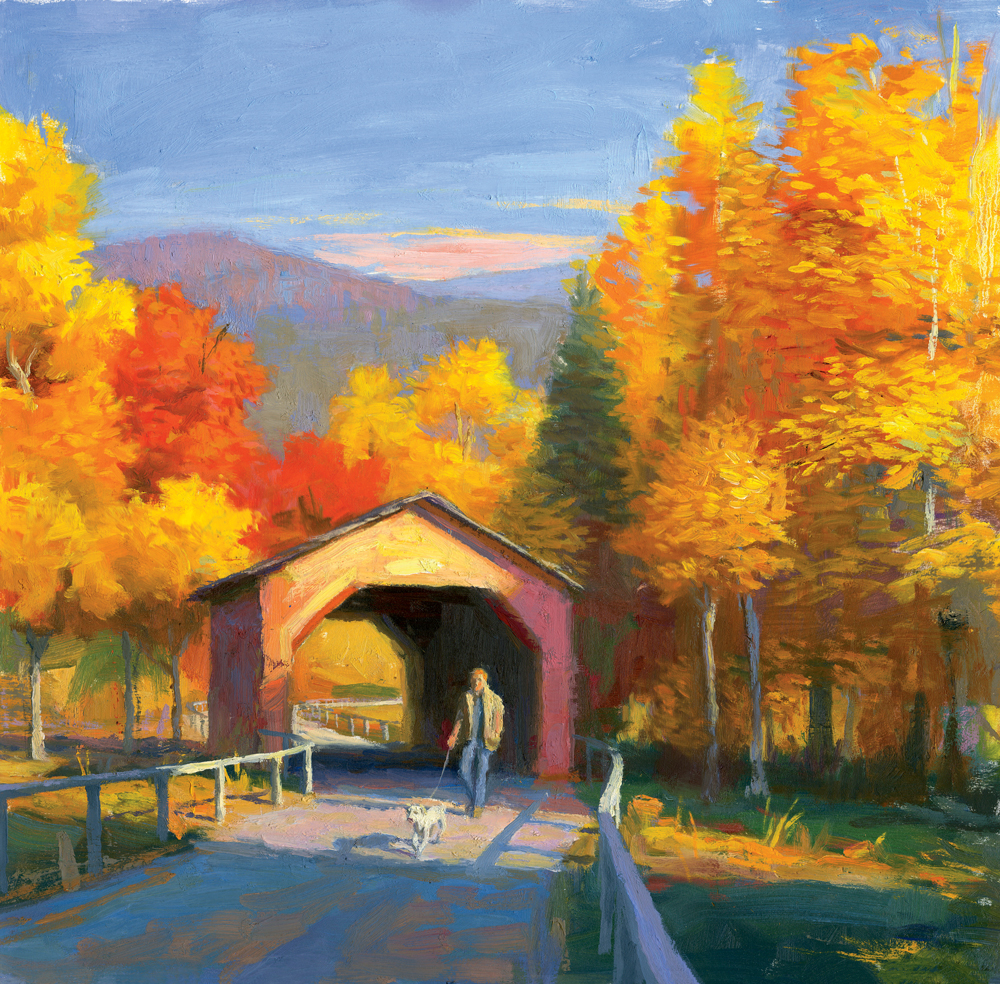

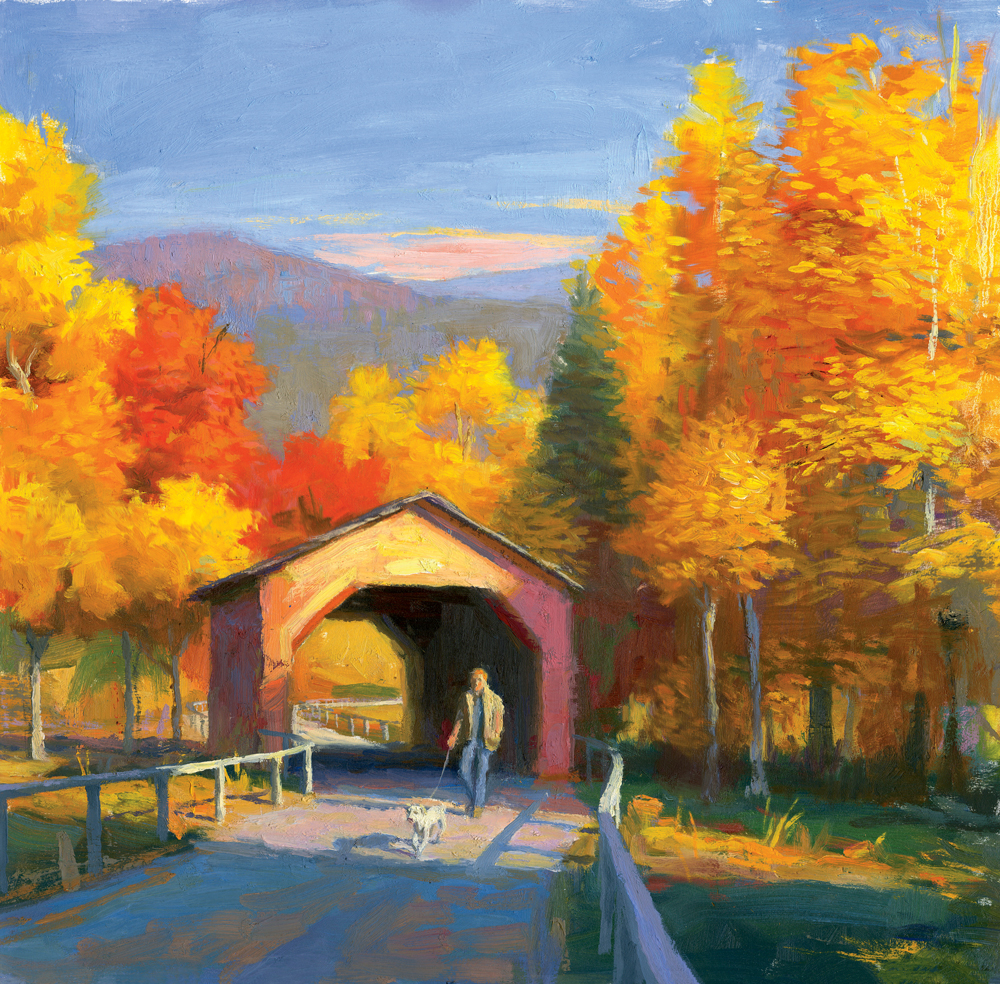

The Protector of Covered Bridges | New England’s Gifts

In the spring of 1954, Milton Graton landed a job that would change his life and the fate of covered bridges around the country, New England especially. A structure mover out of Ashland, New Hampshire, the 46-year-old Graton was a large-scale hauler, moving buildings mainly. Which is how he ended up in Rumney, […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Allen Garns

In the spring of 1954, Milton Graton landed a job that would change his life and the fate of covered bridges around the country, New England especially. A structure mover out of Ashland, New Hampshire, the 46-year-old Graton was a large-scale hauler, moving buildings mainly.

Which is how he ended up in Rumney, New Hampshire, home to a dilapidated, century-old covered bridge that for many years had sat neglected and unused. The bridge was now in private hands, and the owner wanted it moved to another part of town, where it was to be converted into a gift shop. But on the night of July 3, 1954, just a day before work was set to begin, the old bridge collapsed into the Baker River. Now the owner needed it gone. So Graton bought the remains, with an eye toward one day using the still-good timbers. As he worked, he came to admire the bridge’s construction. In many places the joinery had remained so tight that a century of sunlight had failed to penetrate the seams and discolor the wood. By the time Graton had hauled every scrap of wood out of the river, he now felt an obligation to protect it. “I was convinced at that time that to preserve the work of these great, honest, and true carpenters of 100 years ago was the duty of every good citizen who would save for posterity that which would never again be reproduced,” he wrote later in his book, The Last of the Covered Bridge Builders.

With his oldest son, Arnold, Graton took on the work around the country that nobody else could do, or, owing to tight town budgets, wanted to. The Gratons strove to replicate how the bridges had originally been built. They preferred hand tools over power machinery, pulled the structures into place with teams of oxen, and cinched together the framing with long wooden pegs, called trunnels, which they milled themselves. Crowds gathered to watch them work, and parties broke out as the men pulled the renovated bridges into place. In Woodstock, Vermont, in 1968, the Gratons built Middle Bridge, the first new covered bridge constructed in this country in the 20th century. It was 20 degrees below zero when father and son pounded in the last of the roof shingles.

When age slowed Milton down, Arnold helmed the projects. Then, when Milton passed away in 1994, his son became the face of the business. In all, Arnold has rehabbed more than 70 covered bridges and built another 16 new ones from scratch. And their significance means as much to him as it did to his dad. “I think it’s important to have a history behind us that we can use as we go ahead,” he says.

As it was to Milton, bridge renovation is more than just carpentry to Arnold. That’s because the bridges themselves are more than just timbers and trunnels. How they were built, why they were built, tell a story: about how we once lived, how we worked, how we made things. In rural towns all across New England, covered bridges transformed communities. They shortened travel between family members, brought farmers closer to markets, and just made the world a little bigger for so many 19th-century Americans. But once a bridge is gone, a lot of that heritage vanishes with it.

“I can’t think of any builders who’ve done as much for covered-bridge work as the Gratons,” notes David Wright, longtime president of the Vermont-based National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges. “The original old bridges would have been erased. They might have looked like covered bridges, but because they weren’t renovated exactly how they were built, they wouldn’t have been the same.”

—“The Man Who Saves Covered Bridges,” by Ian Aldrich, September/October 2013

Hi! I am an amateur painter and I love the photo of a covered bridge, on your page! Do you authorize me to take it as a model in one of my paintings?

Thank you!

Céline Magnan

Ottawa, On Canada

NB.

Hello Céline. Are you referring to the image on this page? The artist is Allen Garns — you can contact him here: https://allengarns.com/ Thanks!