Magazine

The New Yankee Craftsmen

Against all odds, these Yankee Craftsmen are keeping New England’s traditional arts and trades alive. Learn more about these talented New Englanders.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

Graham McKay, Boatbuilder

Graham McKay grew up near Lowell’s Boat Shop and apprenticed there as a high-school student. Although he left for college and lived in England for a time, he was drawn back to Amesbury, Massachusetts, and the life of a builder. “I’m drawn to old-timey things,” he says. “This place has so much character. Plus, I love playing with boats.” And you can’t beat the view: Perched along the Merrimack River, the shop’s windows frame a perfect and uninterrupted view of the water. The firm dates back to 1793, making it the oldest continuously operating boat shop in the United States. Simeon Lowell first began designing and building his signature dory skiffs, a popular fishing vessel of the time, in the late 18th century. For the next seven generations, Lowells built the boats here, right up through 1976, when Ralph Lowell finally sold the shop to Malcolm Odell. Today, McKay works with many of the same tools—giant chisels and hand planes—and techniques that his predecessors used more than a century ago. Some of these vessels are bought by local boating enthusiasts, others by people just looking for a high-quality rowboat for their families. And one, beautifully painted in deep hues of blue-gray, is waiting for its ride down to New York City, where it will serve as the dinghy for a much larger boat. The shop produces eight to ten of these skiffs a year to sell (in 1911, its peak year, Lowell’s produced 2,029); four to six more are built by students in the classes offered at the shop. A traditional painted dory might run $8,000 to $9,000. McKay says the price keeps the dories competitive with many of the dinghies that boaters buy to trail behind their yachts. There are always several boats propped up in various stages of completion at Lowell’s. Sawdust lightly coats the floor. McKay and the others who spend hours putting these boats together no longer smell the intense aroma of cut wood—once pine, now a mix of cedar plank, mahogany, cypress, and black locust—that permeates the building. The shop now runs as a nonprofit organization, school, and museum. Visitors are welcome to come by year-round and watch the boatbuilding process. “There’s still a market for this,” McKay says. “As a nation, or a world, we’re losing little bits of history, and then we try like hell to get it back.” Lowell’s Boat Shop, Amesbury, MA. 978-834-0050; lowellsboatshop.com

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

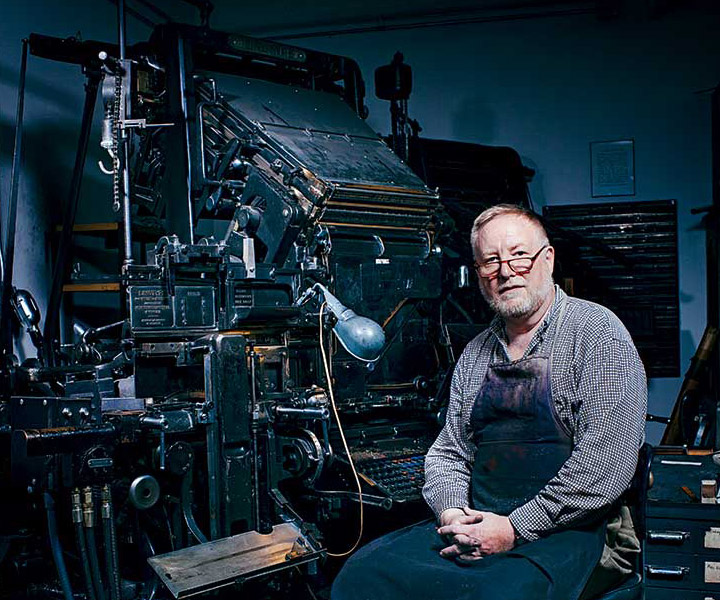

John Kristensen, Letterpress Printer

In his modest workshop on the western reaches of Boston, John Kristensen introduces a visitor to a row of antique machines lining the wall. “These are my dinosaurs,” he says, gesturing at two Linotype and three Monotype machines adorned with metal arms and movable parts. They seem to have personalities even when lying dormant. Kristensen runs Firefly Press, producing letterpress invitations, business cards, notecards, and other printed media. This is the three-dimensional, real-world version of desktop publishing. Kristensen chooses his fonts from among 300 different cases of type. He methodically places each metal letter in turn to form words, proclamations, invitations, and announcements. Then he threads paper into one of his machines, cranks a handle, and watches as the paper and letters meet, leaving behind a distinct impression. “The problem with letterpress is that it’s slow,” he says. He must continually load single sheets of paper one by one and crank the handle hundreds more times to complete just one order. But that’s one of the appeals for Kristensen: “I’m a traditionalist. I believe in the great tradition of letterpress.” There’s something so simple and elegant about the pressing together of paper and type. The imprint revealed is tactile, the smell of ink is intoxicating. But for all its appeal, letterpress nearly disappeared. “This is the way practically all text was produced,” Kristensen explains. “And then it wasn’t fast enough anymore.” A few letterpress printers remain around the country. Several are in New England, all enthusiastic, working to keep the art alive. “The human spirit isn’t willing to let these things go,” Kristensen says. Thanks in part to relationships with Harvard University and some other Boston colleges, Kristensen has much business to keep him occupied. “There’s a very great visceral attraction,” he says. “It’s so much fun.” Firefly Press, Boston, MA. 617-987-0599; fireflyletterpress.com

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

Andrew Pighills, Stone Wall Builder

Andrew Pighills learned his craft out of pure necessity. His father was a farmer; the fields needed delineating. He was 11 when he first assisted with the building of walls on the family’s land in Yorkshire, England. “As a small child I loved jigsaws,” Pighills says. “Dry stone walling is nothing more than a three-dimensional jigsaw.” In his craft, which he now practices from his home in Killingworth, Connecticut, Pighills seldom uses mortar. “The only two things holding a wall together are gravity and friction,” he says. Walls make up the majority of his commissions, but he also creates pillars and other landscape ornaments. (In a break from tradition, he’s also started building outdoor bake ovens, which do require some mortar.) Some of his customers have an understanding of dry stone walling as a craft, but Pighills says many come to him merely by reputation, drawn to the aesthetics but unaware of the method. He later convinces them that the mortar isn’t necessary, since it ultimately weakens the wall. Traditionally, New England stone walls were built with rocks and pieces dug up from the land as it was cleared for farming—a great example of the waste-not Yankee ethos. “Some clients insist that the stone come from their property,” Pighills says, but he uses stone from quarries or stoneyards as well. Working steadily, he can build about six linear feet of a four-and-a-half-foot-high wall per day. He’s outside until late December or early January, when the cold temperatures and frozen ground make construction impossible. He spends the winter indoors, designing gardens and other projects with his wife, Michelle Becker, for their landscape business, English Gardens & Landscaping. He usually starts building walls again in mid-March. “You get so focused on the work, you can let your mind wander,” Pighills says of his craft. “It’s a very rewarding feeling to step back and know that it’s lasting.” Ever aware of history, he has studied the evolution of stone-wall design, both here and in England, and keeps a collection of artifacts he’s unearthed during construction—such as cannonballs from the English Civil War in the 1640s, and antique glass. “Here in New England [the walls are] such a wonderful, historical record,” he says. “I try to make that history a part of people’s lives.” English Gardens & Landscaping, Killingworth, CT. 860-575-0526; englishgardensandlandscaping.com

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

Lisa Curry Mair, Floorcloth Painter

Once made from the worn sails that graced New England’s boats, floorcloths nearly disappeared after the invention of linoleum in the mid- 1800s. But Lisa Curry Mair, who completed her 1,000th cloth last year, has seen somewhat of a resurgence in these decorative and colorful floor coverings. Relying on historical patterns as well as some of her own designs, Muir paints vivid floorcloths and wall murals, all on 100 percent cotton canvas. Her murals mimic those of Rufus Porter, the renowned 19th-century artist and inventor, who is also a distant ancestor. After more than 20 years, she has mastered Colonial, Early American, and country styles, and often does work for museums. Canvasworks Floorcloths, Perkinsville, VT. 802-263-5410; canvasworksfloorcloths.com

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

We know our favorite New England artist/craftsman, Jonathan Gibson of Gibson Pewter, Hillsborough, NH, has been featured before in Yankee several years ago, but this is our go to place for wedding, baby, and birthday gifts. Handcrafted, exquisite items…and Mr. Gibson has expanded to wonderful jewelry as well. His barn/workshop is beautiful to visit, but he ships his beautiful art everywhere. Visit his website or the barn.