The Unfinished Journey of João Victor

Lives are changed when a young asylum seeker in Maine asks a teacher to help him win a national poetry recitation.

After arriving in Maine from Angola in 2016, João Rodrigues Victor rooted himself in a new language and a new home through the work of great poets.

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

On the evening of May 1, 2019, João Rodrigues Victor emerges onstage and strides to the microphone, ready to recite a poem that will take about three minutes but which he feels could impact his life for years to come. Later he will say that when he was waiting in the darkness of the wings, “my heart was beating so fast, I thought I was going to scream. I was overwhelmed sitting there waiting.

I asked myself, Am I good enough?”

He is 18 years old, a high school senior in Lewiston, Maine. In January 2016 he arrived in Maine from Angola with his father and two younger siblings seeking asylum. At the time, he spoke Portuguese and Lingala, a Bantu language, but no English. His father, an outspoken opponent of Angola’s ruling political party, had been imprisoned and beaten. A friend and neighbor who also opposed the government had been dragged from his house by authorities and was never seen again; his father felt that he would be next. He was able to obtain only four visas, so he fled Angola with his three youngest children, leaving behind his wife and three daughters. But the audience filling the Lisner Auditorium at George Washington University for the Poetry Out Loud national finals, as well as the thousands watching across the country on a live stream from the National Endowment for the Arts—they know none of this.

Photo Credit : James Kegley

Here is what they do know: Months earlier, about 275,000 high school students had memorized and recited a poem in their English class, and from that starting line, schools in every state plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands had chosen a champion. What followed was a steady winnowing of competitors, from state regionals to state finals. Now, each state winner has come to Washington, D.C. To the outside world they are all but unknown, but here they are celebrated. They have worked to perfect the art of bringing a poet’s words to life with their own voice—something one contestant has described as “crawling inside the poem.” The day before, 53 champions recited three poems before a panel of judges; only nine were chosen to perform on this night. The winner will receive $20,000, and two runners-up will get $10,000 and $5,000.

Here is something else the audience does not know: A week earlier, when I first met João Rodrigues Victor, he said, “With poetry I can express how I feel. If a day went bad, I recite poems.” As a young man who does not know when, if ever, he will reunite with his mother and sisters, who does not know whether he and his family will be denied asylum and sent back to Angola, he sees many bad days. Asylum seekers cannot apply for federal financial aid for college. He works washing dishes at a hospital every day after school and often does double shifts on weekends, but that money is needed for his family here as well as back in Africa. Though he has been accepted at a small college in western Maine, he does not have the $200 needed for registration. The college told him the cost for his first year would be $20,000.

Onstage in D.C., he wears a raspberry suit coat with black lapels, a red bow tie, and a black shirt, gifted from a J.C. Penney near Lewiston. He has already recited his first poem of the night, Vijay Seshadri’s “Bright Copper Kettles,” which imagines the dead coming to life not as threats but as comforts. His face is intense, his eyes darting left and right. His hands clasp and unclasp. He takes a deep breath. “‘A History Without Suffering,’ by E.A. Markham,” he announces in his lilting accent. He begins: “In this poem there is no suffering. / It spans hundreds of years and records / no deaths, connecting when it can, / those moments where people are healthy / and happy, content to be alive….”

The audience leans in, listening to his voice. After he ends, the ovation is loud and long.

He seems confident and composed, but when emcee Elizabeth Acevedo, the poet and National Book Award–winning novelist, approaches him as she does with each of the finalists after their second performance, he becomes shy, a bit awkward and self-conscious, responding to her comments with “Yes, miss.” She asks about his early memories of books. He smiles, says he comes from Angola, and he did not have books but remembers singing songs. He tells her he discovered poetry only this year. He waves to the cameras and gives a shout-out to Lewiston and to his brother and his sister, who are watching. He thanks the high school teacher who helped him believe he could do this. Acevedo asks him to pronounce his first name, and when he does it sounds like Shu-oun. He knows how strange it seems to American ears, which is why he tells everyone to call him Victor.

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

Journalists are not supposed to become invested in the lives of the people we write about. But as I watch this, I want Acevedo to ask different questions. I want her to ask how he came to recite intricate poems in a language he had only recently learned, and in a way that makes those who hear him feel he is talking just to them. I want her to ask about the first time he met James Siragusa, his teacher, or the last time he saw his mother. If those had been the questions, he would have started his story in a sweltering airplane terminal at 4 a.m. in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And then it would have become clear why he has wrapped his arms around poems as if they were hope itself.

When Victor tells me the story of coming to Maine, it starts like this: “The last time I saw my mom, it was a January night. We had escaped to Congo in a bus. She was sitting with me at the airport. I was looking at her, and she was making sure my tie was OK. She said, ‘You must find your way to succeed. You have to take it.’”

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

The next days are a blur. There’s a flight to Morocco, another to New York, then a bus to Boston, a bus to Maine. Along the way, there are brief stays with those who have already made the journey. One of them advises going to Lewiston, where many African immigrants have settled. Once in Lewiston, Victor’s father fills out an asylum petition. They need to wait six months before he can work, which means they must rely on charities and community programs. Victor remembers dragging his luggage against pavement and the bitter cold—“I couldn’t feel my hands,” he says. “I couldn’t talk.” Mostly, though, he remembers feeling confused and lonely.

Lewiston High School, with nearly 1,500 students, is the largest in Maine. It is also one of the most diverse in New England: Nearly one in four students in the Lewiston school system is enrolled in the English Language Learner program. Victor enters ninth grade, taking beginner English classes, all the while trying to navigate a school and a social landscape unlike any he has known. He finds if he translates all assignments into Portuguese and back into English, he can understand what needs to be done. Slowly, the new language begins to make sense. He grows less shy about asking teachers to repeat their instructions.

In the spring of his junior year, Victor is watching TV when he sees a Maine teenager named Allan Monga reciting Lord Byron’s poem “She Walks in Beauty.” He learns that Monga, a high school junior in Portland, is also an asylum seeker, from Zambia. Monga is in the news because he had won the state Poetry Out Loud competition but was being denied the chance to go to nationals because of his immigration status. Only when his high school and the city of Portland made a legal challenge to the contest’s permanent-resident requirement was he allowed his opportunity. Victor hears the passion in Monga’s voice. “When I saw him,” Victor recalls, “I said, ‘How can I do this? How can a teacher help me?’”

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

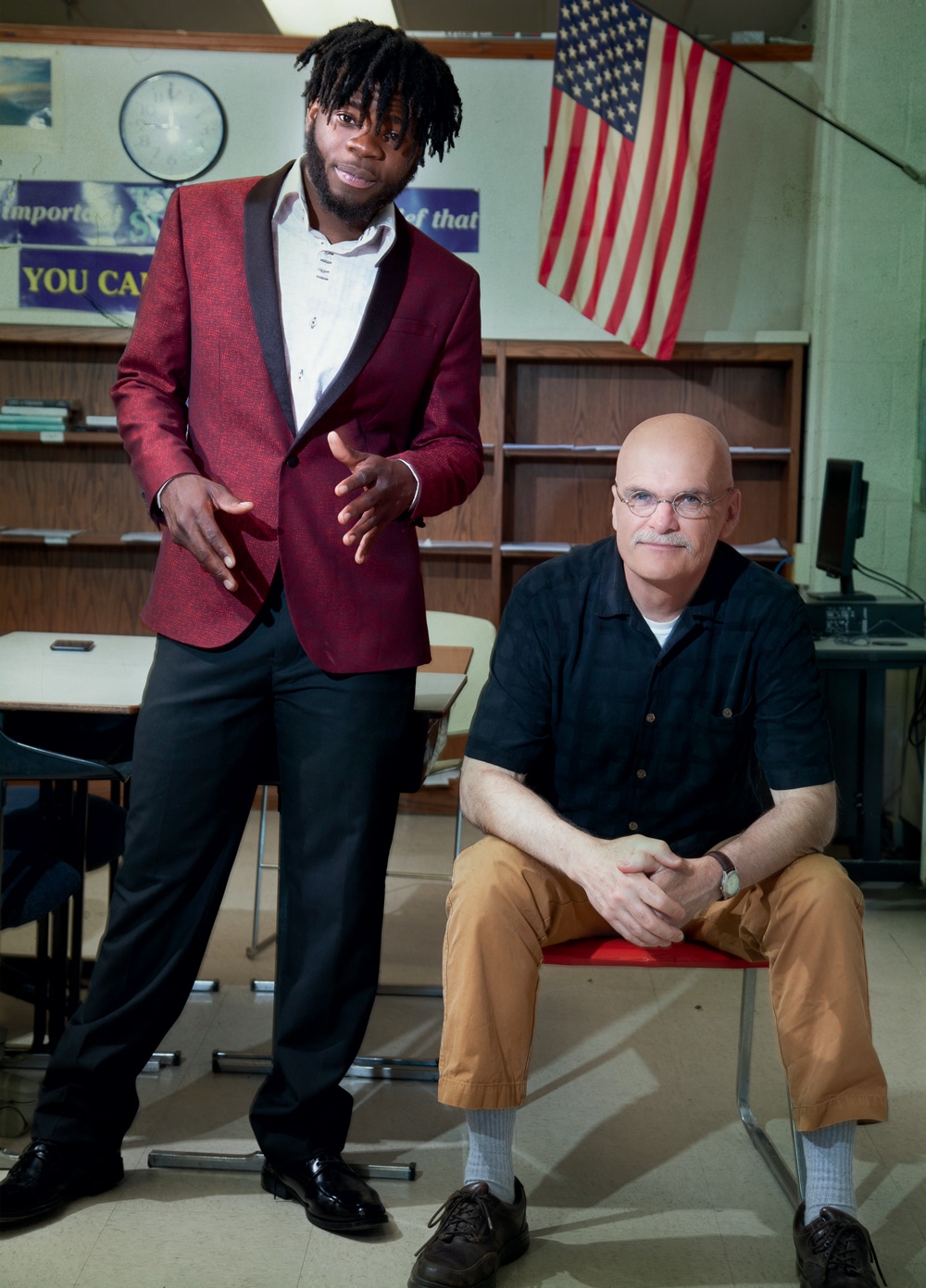

James Siragusa began teaching English at Lewiston High School in 1984, and in 2019 he was set to retire after 35 years. He is soft-spoken, tall and lean, bald, bespectacled. He is one of eight children; his mother, 96, still lives at the family compound by Lake Annabessacook, 20 miles north of Lewiston.

Siragusa has been involved with Poetry Out Loud since it began in 2005, and though he has seen hundreds of his students recite poems, he will always remember the early morning in September 2018 when he was getting his classroom ready for the day and a young man ran in straight from the school bus.

“He said, ‘My name is João Rodrigues Victor, but it’s easier to just call me Victor. Are you Mr. Siragusa? Can you help me do Poetry Out Loud?’” Siragusa tells me. “No one had ever done this. No one had ever come in and said, ‘Teach me. Show me how.’ Victor was so excited, so enthusiastic. I haven’t even heard him yet, but I think, He can do this.”

They begin by choosing poems together. There are more than 900 poems on the Poetry Out Loud website for students to select. “I’d never spent so much time reading the poems,” Siragusa says. “I’d never spent hours. But when I heard Victor read the first time, I knew we had to find poems with pathos and emotional range. He was a natural. You can’t teach expression. He just had it. I wanted to find poems that made you feel.”

Siragusa tells Victor not to memorize any poem until he knows its meaning. It wasn’t just saying words, it was saying words how the poet intended; you had to know it not just by heart but with your heart.

Victor is drawn to the Longfellow poem “The Light of Stars,” and when we meet shortly before he leaves for nationals, I ask him why. “Longfellow had a good life, and suddenly tragedy happens to him and he loses everything,” he says. “His house burns. He loses his wife and he is badly burned. That showed me I have to stay close to my family. When I talk to my mom I am sad. I say ‘I love you’ and I had never said that before.” And then, as casually as humming a tune, he recites: “O fear not in a world like this, / And thou shalt know erelong, / Know how sublime a thing it is / To suffer and be strong.”

Every morning Victor sprints from the bus to Siragusa’s room to practice before the first bell. He is almost always late to class. He returns every afternoon for a half hour more. He keeps asking, “What can I do to improve?” He finds YouTube videos of Allan Monga reciting, and he watches them over and over. He washes dishes at a local hospital for four hours every evening, and when track practice ends he runs the two miles to that job, reciting along the way. After his shift ends at 9:45, he runs the mile to his house. He finishes schoolwork at midnight. He hears his poems in his sleep.

Siragusa solicits coaching advice from poets and people who know theater and voice. When Victor selects “Bright Copper Kettles” to perform in competition, Siragusa makes a video of Victor and sends it to the poem’s author, Vijay Seshadri, a professor at Sarah Lawrence College. (Seshadri emails back, “[P]lease convey my gratitude to João. I’m a very lucky poet to have found such a connection to my world.”) Mentor and student sometimes meet on Saturdays, Siragusa sitting, Victor standing, as if they are in a room with judges and an audience watching.

And then they are. Victor becomes his high school’s champion, then wins the southern Maine regionals in February. At the state finals in March he finds himself seated next to Monga, who is vying for his second state crown and a chance to return to nationals. “I thought, Oh my God, I’m competing against my hero,” Victor says. “He is the one who led me to discover poetry. I couldn’t believe it. But I wanted to win. And only one of us can go to Washington.”

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

At the end they stand side by side, the two finalists. Before the winner is announced, they embrace, seemingly reluctant to let go; it’s a bond between two young men who understand each other. Without Allan Monga, there would be no João Rodrigues Victor onstage. When the emcee announces, “First runner-up, Allan Monga,” the stage erupts with Victor’s exuberance, and Monga bows deeply to the new poetry king of Maine.

In one month, Siragusa and Victor will fly to Washington, D.C., for nationals. Siragusa has waited his entire career to find a student with Victor’s passion. “I thought, God gave me a gift,” Siragusa says. “A parting gift.”

On April 22, 2019, Victor and James Siragusa meet early in the morning to drive to the Maine State House. Victor wears a suit and a bow tie that Siragusa loosens “so it doesn’t constrict his voice,” he tells me. It is a week before nationals, and Victor has been asked to recite at the first Maine Arts and Culture Day. Governor Janet Mills will be there, as well as Maine’s poet laureate, Stuart Kestenbaum. When Charles Stanhope from the Maine Arts Commission introduces Victor, he says, “We are all following his journey.”

Victor recites in the Hall of Flags, a room of marble floors and high ceilings, and when he finishes, everyone stands, applauding. Victor seeks out Kestenbaum and asks if he has any advice. “You’re already incredible,” Kestenbaum says. “You’re not up there showing off. You’re respecting the poem.” A woman from a dance troupe at Bates College approaches Victor and asks where he will attend college. “I don’t know,” he says. “I can’t apply for financial aid.”

Siragusa is introduced to Con Fullam, director of the Pihcintu Multicultural Chorus in Portland. Everyone in the chorus is an immigrant, and they have just returned from singing at the United Nations. When Fullam learns about Victor’s plight, he is blunt with Siragusa. “[Victor] must get legal representation,” he says. “Those who are represented are the ones who get listened to. If you don’t, you are just dust in the wind.”

Afterward, Siragusa wants Victor to see the lakeside compound that’s been in his family since the 1930s, so we drive about 12 miles west. Siragusa’s mother, Helen, is there making lunch for everyone. Victor can barely contain his excitement at the lake, shards of ice rimming the shallows, ospreys overhead, and the absolute quiet of the land. He asks if he can bring a girlfriend in the summer, especially if he finds one.

Inside, the walls are covered with family photos. “This is a house of pictures,” Helen says, and as I watch Victor walking through the rooms, I wonder what he is thinking. For several hours he talks about carrying jugs of water from distant rivers, and meals of bread and sugar water, and how he felt rich when his parents were able to afford tea. He tells of being beaten in school for talking so much, because he always liked the sound of his voice. He talks quickly, as if a timekeeper will cut him off. He says he learned to speak with feeling from listening to pastors in Angola. “If you are passionate, people will feel it,” he says, “and people will want to stand with you.”

Looking on, Siragusa says quietly, “I am learning things about him I never knew.”

In Washington, Victor meets with Maine’s Congressional delegation and recites “The Light of Stars” for Senator Angus King—who then recites a poem back. Victor also meets other young people from across the country, surprising them when he is able to comment on their performances, which he has watched so often he’s memorized their poems. When he sees Janae Claxton, last year’s national champion, he asks Siragusa, “How do you say a female hero?” “Heroine,” Siragusa replies. And this is how Victor greets her.

After Victor is named one of the finalists on Tuesday, he and Siragusa return to the hotel room. “Do you think I have a chance?” Victor asks.

“There are only nine,” Siragusa says. “Everyone has a chance.”

The next evening, May 1, before they leave for the auditorium Victor asks Siragusa to pray for him. “There was an awkward pause,” Siragusa remembers, “and Victor giggled. I realized he meant out loud. I said, ‘Lord, please help Victor to shine his light on his audience tonight. Give him the strength and confidence to express himself from the depths of his soul and to enjoy this moment forever.’”

Then, shortly after 8 p.m., Victor is onstage after his second poem, and Acevedo is asking about his early memories, and soon all nine finalists are standing side by side waiting to hear who will be asked to recite one more poem, which will decide the winner.

Here is where I want to write that, thanks to all his hard work and passion, Victor becomes the Poetry Out Loud champion, is awarded $20,000, and will attend the college that he feels will open yet another new world to him. But sometimes journeys, like stories, take their own path.

“Everywhere I have gone, every competition,” Victor recalls, “I hear João Victor, João Victor. Now, for the first time, I did not hear my name.” He will tell Siragusa, “I let Maine down.”

“Usually when a student is so disappointed, they can hide it,” Siragusa tells me. “Not Victor. I told him he had done so well. ‘What are we going to do now?’ he asked me.”

Late that night, Victor’s phone rings. It is Monga, who tells him how proud he is, that Victor has achieved so much, the first from Maine to be a finalist.

Despite his deep disappointment, when Victor returns to Lewiston he finds he is something of a celebrity. The city names him its first youth poet laureate, and he gives a workshop on recitation at the local library. At Lewiston High School’s awards night, Victor once more recites “The Light of Stars,” and though he cannot see them, tears flow down the faces of many in the audience. A man hands him an envelope; inside it is $2,500, a start toward his hoped-for college life. Bates College honors Siragusa for his teaching career, and Siragusa invites his wife, his mother, and Victor to attend.

Just before he left for the nationals, I had asked Victor what he would do with his drive to excel once he no longer had to pour his life into reciting poetry. “I won’t stop,” he says. “One day I will say to my kids, ‘If you put in the work, you have a chance to dream.’ I am an Angolan man, and look where I am. I won’t stop doing this. I will start writing my own poetry.”

Victor begins performing his own poems on stages ranging from community churches to the Waterville Opera House. But more than anything, he uses his poems to help him face life.

In fall 2019, Victor’s mother contracts malaria, and her sister dies in a bus accident in Congo. “That was the hardest time,” Victor tells me. “I couldn’t do anything. So I went and wrote a poem so I could keep myself calm.”

Right before the school year ends, Siragusa posts a Facebook plea for a lawyer to take on the asylum case for Victor’s family even though they have little money. The mayor also gets involved in the search, which ultimately leads to one of Lewiston-Auburn’s best-known attorneys, Michael Malloy, agreeing to represent the family pro bono. “When someone calls and says, ‘Will you help this amazing person?’ you say yes,” he explains. Before the end of the year, he files the official application for an asylum hearing. He says the family has a compelling case, but with hundreds of new asylum seekers from Angola and Congo continuing to arrive in Portland throughout the summer and fall, it might take two years, or even longer, for the case to be heard.

Victor enrolls in the local community college, but without the discipline that bonded teacher, student, and poetry, he struggles with his business and math courses while washing dishes 40 hours a week. He says he may wait to go back to school, just working to earn money for the family in the meantime. He knows there are colleges where students study drama and poetry and speech, but he doesn’t know how to go from here to there.

Siragusa keeps in close contact with Victor, doing what he has done since they first met: believing in his rare talent and charisma, refusing to let his flame be extinguished. When Victor tells him he thinks performing arts is where his heart will ultimately take him, Siragusa begins writing to people who work in the field of drama—another way of praying, he figures.

This is a journey they are now on together, one with a still-undetermined end. Except now Victor belongs to two families, one uprooted and one with generational roots, and that just may be enough for him to find his own way. “I’m still learning,” Victor says. “I will use my words to get back.”

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen