The Big Question | What’s the Future of History?

Biographer and Historian David McCullough approaches writing a bit like enrolling in college: “I know I’m going to be there for four years, and just think of what I’m going to learn,” he says. The author of 10 titles, all of which are still in print, McCullough’s interests have ranged from the Johnstown Flood to […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

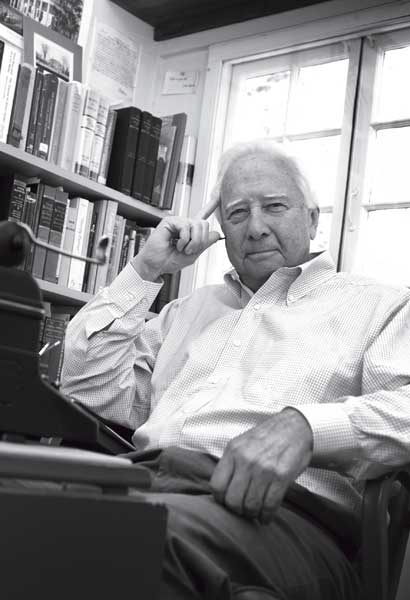

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanBiographer and Historian David McCullough approaches writing a bit like enrolling in college: “I know I’m going to be there for four years, and just think of what I’m going to learn,” he says. The author of 10 titles, all of which are still in print, McCullough’s interests have ranged from the Johnstown Flood to the building of the Brooklyn Bridge to the life of John Adams. His most recent work, The Greater Journey (Simon & Schuster, 2011), came out in paperback this past May. A two-time recipient of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, McCullough lives on Martha’s Vineyard. We spoke with him at his summer home in Camden, Maine.

“When I tell people about how we could revive an interest in history … [I say] bring back the dinner-table conversation. [Growing up,] every night we all sat down together and every night we talked … My grandmother and my father differed greatly in their opinions about FDR. He felt he was the worst thing that ever happened to this country. And my grandmother’s view … [was that] except for Jesus Christ, no more miraculous mortal had ever walked the earth. Their dialogue was memorable, particularly because they were both hard of hearing, so the decibel level got pretty high. But we learned a lot about the New Deal and politics.

“I think human beings need stories. It’s built into us. It’s why we’ve survived as a species. When you think that [for] nine-tenths of all our time on earth, all information essential to survival was passed on by word of mouth … It’s why we watch the stupid television. It’s why we watch stupid commercials … It’s like food, air, salt–we need it. And the problem with how we teach history [is that] the people who write textbooks and the people who sometimes have control in the classroom have never figured that out.”

“I’m very interested in accomplishment, whether it’s the accomplishment of the Brooklyn Bridge or the Panama Canal. Or the accomplishment of a life, out of what seemed to be modest clay, of someone like Harry Truman … I’m also interested in people who had to overcome some real problem … when people suddenly have a moment and see where they’re headed or what they need to do.”

“I think history gives an aid to balancing life. It’s an aid to navigating turbulent times, turbulent waters. It’s an antidote to self-pity and an antidote to excessive hedonism, and the excessive and grossly mistaken view that our time and all of us are the most important thing that ever happened … You see these adolescent clowns in public office in Washington and you think of people like John Adams and Jefferson and Franklin and Hamilton coming out of a population of about two million people. And this is the best we can do? It’s heartbreaking. It’s depressing, and it’s also going to stir us into action, I think. I hope so.”

“If you could build up any muscle to be a historian or biographer, I’d say it’s the empathy muscle. Go out and do empathy exercises. Put yourself in their place. I get very impatient with historians who say, ‘Well, they should have realized how risky that was.’ Or ‘Why didn’t they do [this or that] given the situation.’ Excuse me? They weren’t up on the mountaintop, surveying the whole thing 150 years later the way you are. They were down in the thick of it. They didn’t know what was going to happen next. They didn’t know what was happening a mile away.”

“[Technology has] been very good in many ways. The fact is that the papers of most of the Founding Fathers are now online, [and] it won’t be too long before incredible amounts of material that are available only in rare collections and libraries and archives will be available online … I think where history is going to suffer is that nobody writes letters anymore. And nobody keeps diaries anymore. Certainly nobody in public life keeps a diary anymore. They don’t dare; they can be subpoenaed and used in court against them. So I don’t know how future historians are going to write about us … I wouldn’t be all that surprised if future historians don’t have much about us to go on.”

“At one point I started off to write a book about Picasso. I didn’t get far into it, maybe three months of serious study, and I just thought he was awful. Not just because he was mean and conceited and hypocritical, but his life to me was essentially boring. He changed his female partners often and he painted. And that’s about it. He was a huge success right at the beginning. He never had to struggle up the mountain. Here’s the guy who painted Guernica, the great supposed testament to the evils of war, who lived through the German occupation of Paris primarily worried about how his tomato plants were doing.”