Fannie Farmer | New England’s Gifts

Fannie Farmer changed the world with a simple idea: that home cooking was a serious pursuit. Learn more, plus our take on 4 favorite recipes.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Julie Bidwell

When Fannie Farmer died 100 years ago, her name was a household word. It adorned a cookbook that had already been a best-seller for two decades. Even today, about four million copies later, people who have never even boiled water know her name.

Her name, yes. But when she died, almost nothing was known of her life.

Fannie Merritt Farmer was born in Boston on March 23, 1857, to John Franklin Farmer, a printer and editor, and Mary Watson (Merritt) Farmer. She grew up in nearby Medford, planning a future that centered on going to college. But calamity shattered her plans while she was still a teenager. It’s not clear whether she experienced a stroke or contracted polio, but the illness left her with a pronounced limp.

Her doctors forbade a formal education. Slowly she rallied and became fascinated with cooking. In 1887, at age 31, she entered the Boston Cooking School, where Mary Bailey Lincoln was the school’s first principal.

Fannie’s happy mix of logical and intuitive skills must have burst into flower in that congenial atmosphere. She had scarcely graduated in 1889 when she was asked to return as assistant to the principal. Within two years, she was the principal herself.

Fannie’s view that cooking should be as much a science as an art caught up early with the casual measurements of the time. Directions were then given in approximates: rounded teaspoons (any old teaspoon would do), heaping cups (use the cup of your choice, whatever its size), a walnut-sized lump of this, a dab of that, and so forth. There had been occasional faint murmurs among professional cooks on the matter, but no one had thought to do much about it.

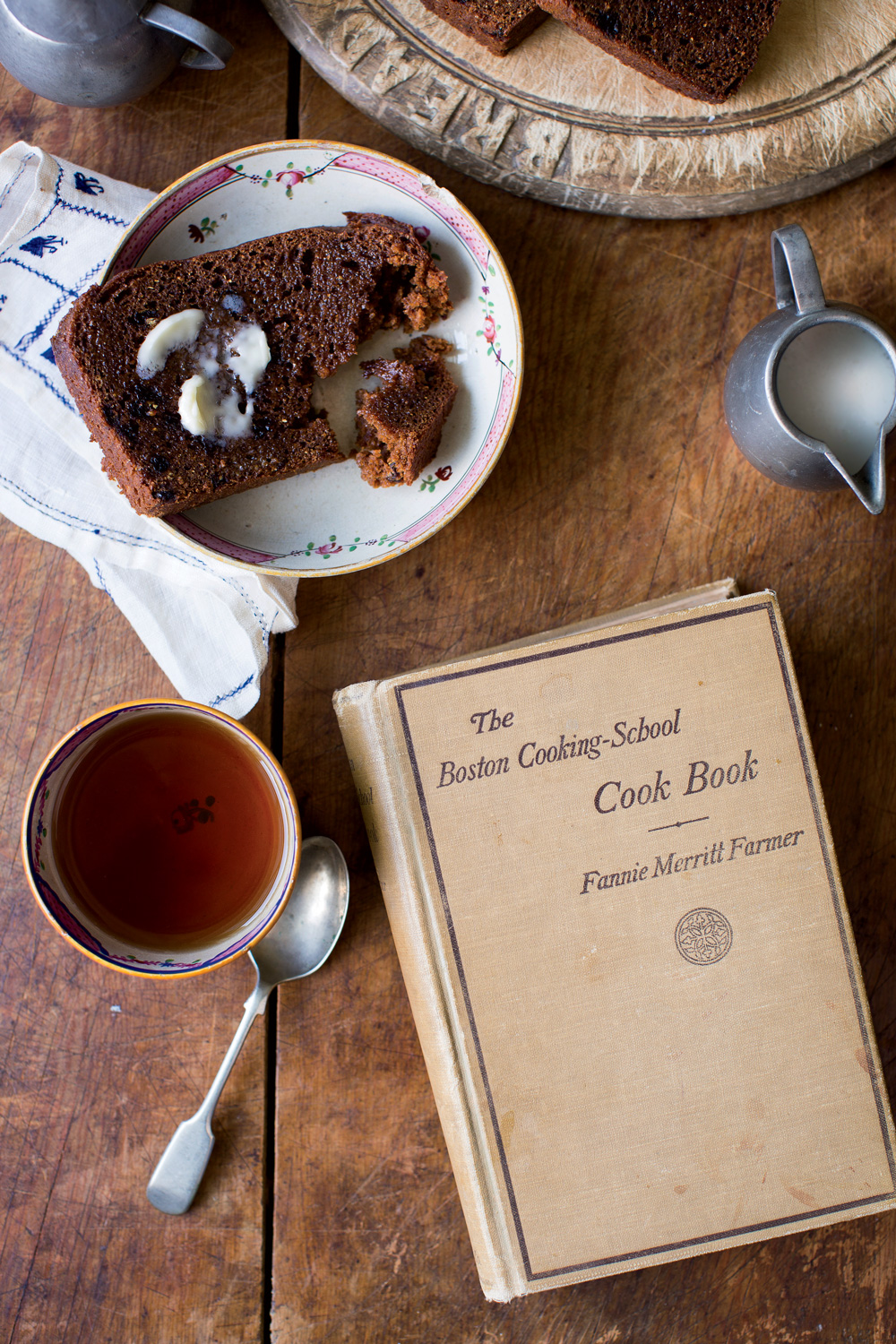

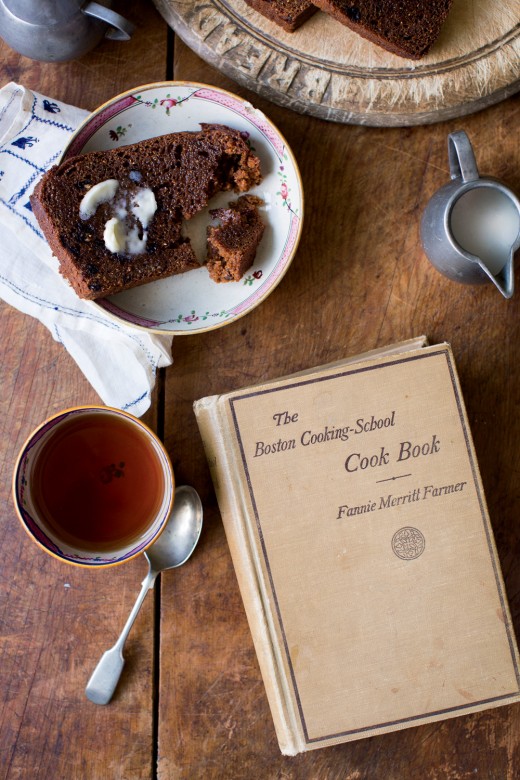

For Fannie, it became a crusade. In her cookbooks, and indeed every time she put pen to paper, the admonishment to scrupulous measurement was repeated. “Correct measurements are absolutely necessary to ensure the best results,” she wrote in The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, which was first published in 1896 and eventually came to be known around the world simply as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook. It featured hundreds of clearly written recipes tested not only by the author but by students and faculty, and was crammed with brisk information, chemical expositions, the anatomy of flesh and fish, household hints, and lists of menus. She took it to Boston’s most respectable publishers, Little, Brown and Company. When they turned her down, she persuaded them to bring out 3,000 copies by agreeing to pay for the printing (she shrewdly kept the rights). It became one of the all-time best-sellers, went through 12 revisions and innumerable printings, and in a very altered form is still in print today.

For the book’s form and much of the nature of its content, Farmer owed a great debt to her predecessor, Mary Bailey Lincoln, who wrote Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book in 1884. But where Mrs. Lincoln was chatty and confidential, Miss Farmer was sweeping and firm.

Take soup, for example. “Nothing,” Mrs. Lincoln wrote, “can be easier than to make a good soup if one only knows how and has the will to do it.” With no apology and no coddling, Fannie, on the other hand, ran her readers through masses of scientific data. She gave them a sense of dignity in their work, but she also offered them reassuring, unequivocal authority.

In 1902, after 11 years as principal of the Boston Cooking School, Fannie opened Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery on Huntington Avenue using funds from the success of her book. She not only ran the school but also reached a wide audience with her monthly food columns in Woman’s Home Companion. She wrote other books, too, though none of them had the success of her first. Among them was a 1904 work called Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent. She liked to say that it was her most important work.

Then there were her popular lecture demonstrations, given twice every Wednesday at the school. In the morning she addressed housewives; in the evening, professional cooks. Often dressed in white, which must have effectively set off her red hair, and with her blue eyes even more intense behind rimless pince-nez, she would talk her way through a formidable array of dishes. She doesn’t seem to have been a greatly creative cook; her gift was more analytic. But her shyness seemed to disappear on the platform, and her talks were frequently reported in the Boston Transcript.

Fannie eventually suffered a stroke around 1908 that left her unable to walk. She was to spend the remaining seven years of her life alternating between crutches and a wheelchair. Her response to this threat was to live wisely and carefully and gloriously despite it. She continued to run the school, turn out books, write her columns, and give her lectures, the last only 10 days before she died, “keeping herself alive by sheer force of will,” according to journalist Mary Bronson Hartt, who wrote a post-humous remembrance of Fannie Farmer in the December 1915 issue of Woman’s Home Companion. Her subject at that last lecture wasn’t life and death; it was bread. A reporter from the Boston Transcript detailed the demonstration, describing seven kinds of bread, biscuits, and dumplings that “she turned out with dispatch.”

Fannie Farmer died on January 15, 1915. The Companion ran her columns for the next 11 months without mentioning her death. The last column contained many of the staunch New England dishes that had come to be associated with her. Among them were Boston baked beans, steamed brown bread, baked and stuffed haddock, Indian pudding, and salt codfish balls. It was a fitting farewell.

—adapted from “The Quintessential New Englander,” by Lisa Hammel, September 1985; recipes adapted by Molly Shuster

Note: The following recipes are all adapted from the 1896 and 1910 editions of the Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, published during Fannie Farmer’s lifetime. We’ve updated each one to appeal to modern tastes but have left the essence of the recipe intact. All changes are mentioned in the recipe headnotes.

Photo Credit : Julie Bidwell

My go-to cookbook for brownies, Viennese crescents and lace cookies!