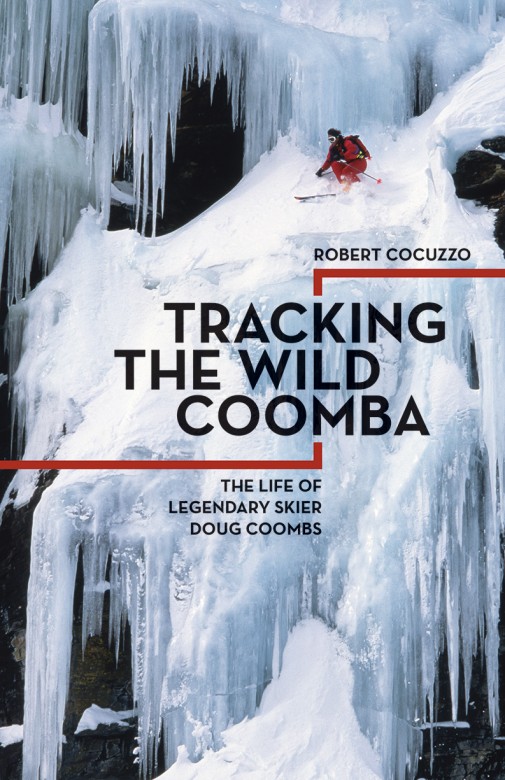

First Tracks | Adventure Skier Doug Coombs

In this excerpt from a new biography on adventure skier Doug Coombs, author Robert Cocuzzo tells the story of Coombs’s early years and the accident that forever changed his life.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Arguably the greatest adventure skier to ever live, Doug Coombs pioneered hundreds of first descents down the biggest, steepest, most dangerous mountains in the world. His place as the best of his sport was confirmed in 1991 when he won the very first World Extreme Ski Championships in Valdez, Alaska. Yet, perhaps Coombs’s greatest legacy was as a guide, leading people on wild adventures and giving them the best days of their lives. His was a life that inspired countless others, right up until his tragic death in 2006, the result of an attempted rescue of a fellow skier.

While his fame began in the tall peaks of the American West, it was in his native New England where Coombs’s legend and his love of skiing were born. In this excerpt from a new biography on Coombs, Tracking the Wild Coomba: the Life of Legendary Skier Doug Coombs (Mountaineers Books), out this month, author Robert Cocuzzo tells the story of Coombs’s early years and the accident that forever changed his life.

Bedford, Massachusetts, in the mid-seventies was a vortex of freedom for a kid like Doug Coombs. Coming off the swinging sixties, hip young teachers were experimenting with new methods of education that were a far cry from the authoritarian style of the fifties. They introduced an open-door policy at Bedford High School, allowing juniors and seniors to come and go as they pleased like it was a college campus. Teachers figured if they treated students like adults, they’d act like adults. The experiment didn’t work out quite as they planned, especially when it came to Coombs.

Coombs skipped school on more than one occasion, leading his buddies on wild adventures throughout New England. From their neighborhood in Bedford, they bushwhacked through the woods down to the interstate, where they hitchhiked north to New Hampshire and spent the day hiking in the White Mountains and snorkeling in the Pemigewasset River. It was in these mountains that Coombs felt most alive. He had a habit of stripping off all his clothes and running barefoot through the woods at top speed under the moonlight. He’d jump into the rapids of the Kancamagus River and bound off boulders downstream as if he were skiing moguls. “He was just unstoppable and awesome in the mountains,” remembered one of his childhood friends. “He seemed like a natural mountain creature, like a bull elk, born to roam the mountain ridges.”

Everything was possible in Coombs’s mind, and he did it all in his own way. If he and his buddies couldn’t hitch a ride up to the mountains, they hopped on to their bikes and pedaled a hundred miles or more to spend the night under the stars. They embarked on long endurance hikes from Vermont, marching thirty miles a day until they reached northern Maine. After reading about winter camping in a magazine, Coombs went off with a friend and hiked Mount Washington in subzero temperatures, wearing blue jeans and beat-up boots. “What fun he was to be around,” remembered another childhood friend. “He had this wild energy like nobody else I’d ever met.”

This wild energy spilled into everything. He had a freak ability to nap whenever the mood struck, and it wasn’t uncommon in Bedford to find Coombs’s bike pulled to the side of the road with him fast asleep alongside it in the grass, as carefree as Tom Sawyer. Once, when a state trooper conducted a field sobriety test on him, Coombs leaped onto his hands and walked thirty feet down the yellow line and back again. Springing back to his feet like a gymnast, Coombs flashed his big grin as if to say “ta-da!” The trooper just shook his head and let him go.

Doug Coombs’s fun energy came off him in intoxicating waves that drew a devoted tribe of friends with him wherever he went. Many vied for his attention, but if he knew anything about his popularity, he never let on. He was modest and had friends in all circles. No one fell outside Coombs’s boundaries because he simply didn’t seem to have any. There was a glow about him, and as he got older, it became blinding, mesmerizing people like moths in a porch light.

***

At sixteen years old, Doug Coombs stood over six feet tall and had a long, rectangular head that his body was still catching up to. He had a square jaw and a tree trunk for a neck, and his auburn hair was long and straight. When he parted it at the corner of his brow, he was a handsome young man. Coombs liked to say that he was 160 pounds with each of his legs weighing 50 apiece. These powerful legs could end schoolyard brawls by squeezing his opponents into submission. A snowball fired from his arm came in like a comet and sent kids scattering for cover. “If he got in a fight, he’d be all elbows and knees,” remembered one of his lifelong best friends, Frank Silva. “You didn’t want to mess with him.”

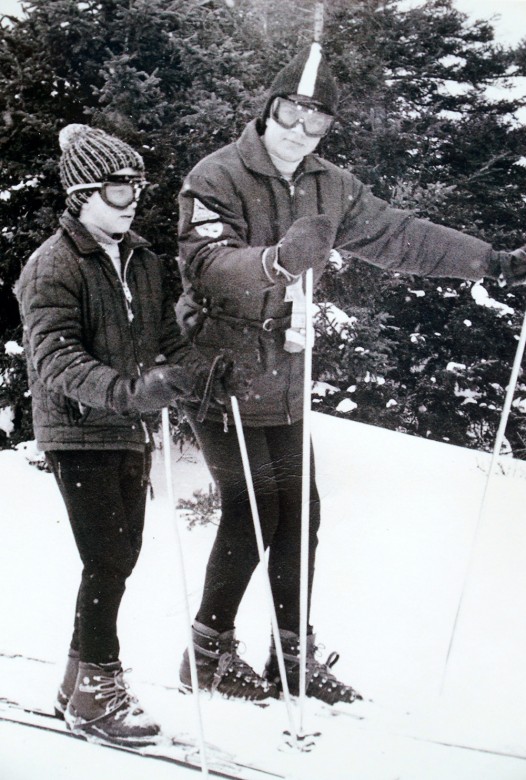

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Robert Cocuzzo

Yet as a physical specimen, Coombs did have his flaws. His vision was atrocious, requiring him to wear thick Coke-bottle glasses, and he suffered from severe childhood asthma, which he eventually outgrew. Despite these ailments, Coombs ran the hundred-yard dash in eleven seconds. He kicked a soccer ball like a mule. When he played halfback on the football field, his might was unmatched—and all the coaches in Bedford seemed to know it. If the Bedford Buccaneers were on the goal line, they handed the ball off to Coombs for the touchdown.

One day, he walked into his home on Wilson Road to find his mother sitting across the kitchen table from Bedford High School’s football coach. The coach wanted Coombs to focus strictly on football and was hoping his mother would convince him to give up his other sports. Whatever case the coach made apparently wasn’t persuasive enough, as Coombs ended up quitting football entirely after his sophomore year to play soccer. There was a rigidity to football and the way it was coached that didn’t line up with Coombs’s freewheeling sensibility. Too much “yes sir, no sir.” Football was a fun game, but that’s what it was to him: just a game. Soccer, too, was just a game. Skiing, though—skiing was so much more. Skiing was like breathing to Doug Coombs. He couldn’t live without it.

“In the middle of summer I used to sit there and stare at books in the library that had snow-covered peaks, thinking, Oh man, I got six more months till winter?” Coombs remembered. “And that was when I was ten years old. There was obviously something ingrained in me about snow.” Indeed, for the quote in his 1975 high school yearbook, Coombs wrote, “There’s no such thing as too much SNOW.”

***

The Coombses were a ski family, and within their middle-class neighborhood it wasn’t an uncommon thing to be. But if each family in Bedford kept a tally of the days they logged on the mountain during each season, the Coombses were most definitely in a league of their own. “After he’d ski for the weekend, Doug would get on the bus Monday and we’d all listen to his ski stories,” remembered Frank Silva. “He’d just be so excited, sort of foaming and frothing at the mouth; his clothes would be all twisted and wrinkled, and he’d entertain us with his stories of how much fun he had skiing that weekend.”

Many kids in the neighborhood had Coombs’s parents, Janet and Gordon, to thank for teaching them how to ski. When the Coombses’ station wagon headed up north each weekend to New Hampshire, Maine, or Vermont, friends of Coombs and his older siblings, Nancy and Steve, were usually in tow. “They did so much for me and had such an influence on me,” said Silva. “Mr. Coombs would buy me lift tickets to the ski area; my parents didn’t give me any money to get a lift ticket. He did. I didn’t have any ski pants and he gave me some. He’d wax our skis and tune our skis. He provided us with a place to stay, and Mrs. Coombs would feed us. They would just say, ‘Go out and have fun.’” The Coombses’ door was always open. When trouble arose in other children’s homes, whether it be a death in the family or an abusive parent, they found refuge at the Coombses’. They became family.

Skiing was the backdrop to Janet and Gordon’s storybook marriage. Gordon Coombs had met his future wife, Janet Brown, in the second grade, when he used to dip her pigtails in the inkwell on his desk. The ink ran deep, and they had been together ever since. After he completed an engineering degree at Tufts University and a tour in World War II, Gordon joined Janet and other Bostonians in catching the Sunday Winter Snow Sports Train up to North Conway, New Hampshire. For $4.35 round-trip, they jammed into one of the twelve railcars leaving Boston to go ski in leather boots strapped to long wooden planks. When they married in January of 1950, Janet and Gordon celebrated their honeymoon by skiing in Stowe, Vermont. Seven years later, when Douglas Brown Coombs came into the world with ten fingers and ten toes, “future skier” might as well have been written on his birth certificate.

His love for skiing began by the time he could fit into ski boots. Many frigid nights of his early childhood were spent careening down a makeshift run he linked together through the backyards of his neighborhood in Bedford. “Even when I was a little tiny kid, I would try and ski every day,” Coombs remembered. “Where I lived, I could even go skiing in my backyard. My parents would flip the light on and I’d ski at night.” In the glow of porch lights, Coombs rushed down the icy slope, driving his legs to squeeze every bit of speed out of the three or four turns he could muster before grinding to a stop on the pebbled pavement of his driveway.

When the backyard lost its luster, Coombs graduated to skiing a steep stretch of woods across the street that the kids dubbed “Suicide Six.” Most in the neighborhood braved Suicide Six on toboggans or Flexible Flyers, while Coombs took to the icy slope on skinny wooden skis with metal edges. When plows piled snow high along Wilson Road, Coombs climbed up onto the roof of his house and skied off into the snowbanks. He dazzled friends by performing fifteen-foot backflips off small jumps they built on the slope of a local dairy farm in Bedford, where the owner had installed a rope tow. “He didn’t ski,” one of his friends remembered. “He flowed. He floated. So smooth it was unreal.”

When Coombs’s older brother, Steve, got his license, he’d drive up to Wildcat Mountain every weekend with his friends and siblings. “We’d throw Doug, who was the youngest of all, in the back. He was sort of like the kid brother that had to go with you if you wanted the car,” said Steve Coombs. “When you’re in high school with your friends, and you have your little brother tagging along, that could be less than perfect, but it ended up being just fine.” On the slopes, Coombs shadowed his brother and sister, following them off the trail and into the woods. What he lacked in experience, he made up for in sheer athleticism and gusto.

Coombs wielded his strength in astounding ways. Some years later, when Steve moved up to Vermont to work at Smugglers’ Notch Ski Resort, his younger brother became a frequent visitor. During one of these visits, Coombs was skiing in deep snow outside of the resort when one of his friends blew out his knee. “Doug just said, ‘Put him on my back,’” remembered Frank Silva, who was with him that day. “He skied him out. The guy must have weighed two hundred pounds.” As much as it was a feat of athleticism, Coombs’s skiing was the result of a mental gift. He possessed a mathematical mind that computed terrain faster than he skied it, effectively slowing down time and extending his window to maneuver. His grandmother taught him at a young age to play chess, and even when she fell ill and was placed in a nursing home, Coombs would sneak in through her window after visiting hours to set up the pieces for a match. Pretty soon he became unbeatable.

His skiing mimicked his chess play as he visualized many moves down the line and executed each turn like he had done it a hundred times before. Once Coombs skied a run, he never forgot it. He had a photographic memory for mountain terrain.

As captain of the Bedford High School ski team, Coombs was a complete racer. In those days, ski racers competed in both alpine and Nordic events. Coombs dominated the slalom at Nashoba Valley, winning nearly every race he entered. On the cross-country course, he competed on skis his father crafted from old alpine ones in his workshop, and Coombs finished near the top. By his junior year in 1974, he’d earned the hallowed Dual County Skimeister Award, recognizing him as the best all-around talent in ten towns.

***

As Coombs’s skiing progressed, he was drawn farther away from the racecourse to the snow that fell outside the resorts’ groomed corduroy. He’d shoot through the woods, snaking around trees, jumping off rocks, and skiing down riverbeds and frozen waterfalls. “No one ever said to me, ‘Don’t go off the trail,’” he recalled later. “We were off-piste skiing when I was seven, ten. I just didn’t think of it as that. I just thought it was going through the trees.”

It was ultimately his father who exposed Coombs to the full potential of skiing in the backcountry. Early one morning Gordon Coombs packed up the family’s station wagon and drove his three kids to the base of Mount Washington. After pulling into the parking lot at Pinkham Notch, the four of them set off hiking with skis on their backs. “I didn’t realize it was this two-hour slog through the forest . . . it was pretty miserable, really,” Coombs said. “Then all of a sudden you pop out of the trees and there’s this two-thousand-vertical, forty-five-degree face covered with snow. It was amazing.”

Carved into the east face of Mount Washington, Tuckerman Ravine was as close to the Alps as a kid from Bedford could get on a tank of gas. Many ski historians point to Tuckerman as the birthplace of extreme skiing in the United States. While the steep glacial cirque saw its first ski track in 1913, it wasn’t until the 1920s and ’30s that Tuckerman Ravine became a wild proving ground for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of skiers during the spring season. Collegiate slalom races, Olympic tryouts, and grueling endurance races known as the American Inferno were held in the ravine’s natural amphitheater. In April of 1939, Austrian-born skier Toni Matt dusted the American Inferno’s eight-mile course in six minutes and twenty-nine seconds, hitting speeds of up to eighty-five miles per hour. Matt’s straight-line descent became the stuff of legend, and Tuckerman emerged as the earliest theater for extreme skiing in North America.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Robert Cocuzzo

After 2.4 miles of switchbacks, the trail from Pinkham Notch gave way to the sight of a magnificent bowl, so steep and snow filled that it looked designed for no other purpose than skiing. Due to Mount Washington’s violent winter weather, most skiers waited for the spring to hike up to test themselves on Tuckerman’s steeps. When the sky was clear and the sun was out, hundreds of people sprawled out on the Lunch Rocks at the bottom, sunbathing, drinking, and watching the skiers above.

This lightheartedness vanished once a skier reached the top of the ravine and looked down its headwall. Spectacular falls were common. Botch one turn, and gravity took care of the rest. Then there was the avalanche risk. Pitched at upward of sixty degrees in some spots, the slope could have a winter’s worth of snow precariously clinging to it, like dynamite just waiting for a trigger. Massive slides carried skiers eight hundred feet to the bottom. Of course, this element of danger was part of the appeal, and not surprisingly, Coombs took to the ravine instantly.

“There’s nobody out there with signs. There’s no ropes. There’s no patrolmen. There’s nobody taking care of you on the slopes like all the ski areas,” Coombs said of Tuckerman Ravine years later. “You’re on your own. You have to make decisions on your own. And when you’re sixteen years old, you make a lot of bad ones.”

One of those bad decisions came when he and his buddy Frank Silva decided to ski Tuckerman one February. Although people do ski the ravine in the winter, it’s attempted only in ideal weather conditions. Mount Washington is one of the deadliest mountains in the world due in large part to its ferocious, unpredictable weather. Winds can gust over two hundred miles per hour, while the temperature can drop to thirty below. As far as Tuckerman itself is concerned, avalanches are an especially violent killer.

“We were clueless on avalanches, we didn’t know anything about the stuff,” said Silva decades later. “We knew there were such things as avalanches, but we were never worried about it at all.” It was snowing heavily as the two boys set out hiking up the ravine. When they were halfway up, Coombs and Silva dug a hole in the face and climbed inside to eat lunch. As they chewed on their sandwiches, snow began cascading over the opening of their snow cave, lightly at first, and then harder and harder. The two boys shot each other a look. Suddenly a massive avalanche ripped by the opening of their hole like a freight train.

When the snow settled, Coombs and Silva popped their heads out of the hole. Blocks of snow and debris were strewn all over the slope. Down at the base, people were frantically searching for them. They thought the two boys had been buried. “We pop out of this little hole and start hiking again,” remembered Coombs, “and all of a sudden they start screaming at us, ‘Get off the mountain! Get off the mountain!’”

Tuckerman Ravine became the backdrop for the inspired skiing of Coombs’s adolescence. The chutes and steeps honed all his abilities as a racer, while his imagination allowed him to pioneer new routes that no one had ever considered. He and his buddies camped at the base of the ravine for days on end, spending hours hiking up and skiing down. One sunny afternoon in 1973, Coombs set off up the ravine by himself. “We’re down at the Lunch Rocks having a snack, and we heard this ripple go through the crowd,” said one of his buddies, Bill Stepchew. “People were yelling, ‘Look! Look!’” Every set of eyes shot to the headwall at the summit to find a lone silhouette perched over a steep and narrow chute that cracked down the center of the rocks like a lightning bolt.

“Oh my God . . . it’s Coombs!” Stepchew yelled out. Silence passed over the crowd of hundreds. Coombs plunged into the chute. The snow came up to his neck and immediately avalanched. From below, the crowd could make out only his arms punching out from the rushing river of white, his head bobbing side to side like a prizefighter’s. He executed a number of precise turns in the chute before bombing out the bottom in an explosion of sluff. The crowd erupted. Their cheers reverberated off the snow walls and filled the ravine with an electric buzz that gave his buddies goose bumps. Pride burst through their chests. “Everybody is looking over at us and clapping,” remembered Stepchew. “We couldn’t have been more proud of him and ourselves for just being with him.”

Entering the spring of his junior year of high school, Coombs was poised for a promising skiing career. His prowess on the racecourse would likely earn him the attention of college scouts, and then perhaps he’d point his skis on the professional race circuit. Coombs’s future looked bright and boundless, but then the unthinkable happened.

***

As a teenager, most mornings Coombs didn’t so much sleep in as hibernate. He squeezed every last second out of his alarm clock’s snooze button before dragging himself out of bed to chase the school bus down. His morning sluggishness wouldn’t have been such a problem had he not been responsible for a daily newspaper route. Eventually Coombs devised a way to get the job done without missing a minute of his beauty sleep by bringing the papers onto the school bus and hurling them out the window as they drove by each house.

Despite his penchant for sleeping in, on the morning of April 13, 1974, Coombs was up before the roosters. It was the Saturday of Easter weekend, and Waterville Valley Resort had its chairlifts running earlier than usual to ferry people to a special service at the top of the mountain. Coombs and his buddies Bill Stepchew and David Underwood had no intention of attending the service, but they were happy to sneak onto an early chair.

With the sun peering down from a cloudless sky, Waterville Valley had full-on spring skiing conditions. Coombs wore blue jeans, a baggy gray sweatshirt, and a white bandana wrapped around his head that gave him the look of a kamikaze pilot when he barreled down the slopes.

By ten thirty, the temperature peaked at seventy degrees and rivulets of meltwater ran down the mountain and across the trails. The snow was as wet and slushy as it could be when the three boys pulled up to the top of the World Cup T-Bar. Stretching 1,500 feet below, Tommy’s World Cup Run pitched and rolled down some three hundred vertical feet. The trail was named after Waterville’s founder Tom Corcoran, who opened the resort in 1966, and it would later be made famous by Coombs’s ski racing heroes, US Olympians Phil Mahre and Steve Mahre. Coombs was more familiar with this run than any other on the hill. That winter he had spent weekends competing on the resort’s ski team, and this was their training course.

The sixteen-year-old surveyed the course below, how it pitched steep, flattened out, and then steepened again. “Somebody had set up a camera tripod and was taking pictures on about the middle of the trail,” remembered Bill Stepchew. “Cameras always made Doug do things that were camera worthy.” Coombs spotted a crude jump built on the side of the trail. He nodded to the mound of snow and then shot Stepchew and Underwood his unmistakable grin: Watch this.

Shoving off, Coombs smeared his turns down the first steep. Even in the sluggish snow, he moved with effortless grace. His upper body remained perfectly balanced while his legs swooped below him in unison. His poles struck the snow purposefully, waving through the air like two magnificent scepters. With the jump in his crosshairs, Coombs straightened out his skis and dropped into a crouch. He gained speed and made a line for the jump.

“He launched off this ramp and just went as high as I’d ever seen anybody go—like telephone-pole high,” remembered Stepchew, who had skied down below the jump with Underwood to watch. “He flew so far that he was going to land on the flats.”

But after takeoff, Coombs’s body started rolling forward. His legs spread apart, and for an instant he looked like he’d just been bucked from a bronco. He flapped his arms, trying to right himself, but it was to no avail. Coombs’s ski tips hit first, catching in the wet snow and catapulting him directly into the ground with punishing force. His face slammed into the snow with the violent snap of a rattrap.

Lights out.

Coombs lay unconscious in the snow. “He was just lying there like a rock, for maybe fifteen seconds,” Stepchew said. He and Underwood were shocked. The fall wasn’t a spectacular rag doll, but the force of it was nauseating to witness. Coombs had gone from poetry in motion to a heap of helpless body parts. “Doug never fell, and the sight of it just didn’t register.”

Coombs’s eyes fluttered open. Wet snow was packed up his nose and in his ears and mouth. He pushed himself up to his feet, looked around for a second, and then blacked out again. His face slammed back into the snow. His friends began feverishly sidestepping up to come to his aid, but before they could reach him, Coombs shot awake for a second time. He was furious. He never fell, and now his inability to control his body added insult to injury. Coombs jumped to his feet, angrily clicked his boots into his skis, and bolted to the bottom without a word to his friends.

It took only a couple of turns for Coombs to realize that the crash had bruised more than just his pride. His back ached and he felt woozy. Reaching the lodge at the base, he clunked his way to the first-aid office, but no one was there. He rang the bell, but still nobody. Since it was Easter weekend, volunteers were running the resort’s medical office and everyone was apparently out on a ski break. After a few minutes, Coombs decided there was nothing better to do than get back on the lift.

When he slid off the chairlift at the top of the mountain, Coombs felt dizzy and tired. Maybe he just needed to sleep it off, he thought, so he skied into the woods behind the mountaintop restaurant, popped off his skis, and fell asleep in the snow. Meanwhile, his friends had no idea where he was. Coombs’s parents had rented a condo near the mountain that winter, and they were up for the Easter holiday. The boys concluded that Coombs must have met up with them. They never imagined he was passed out in the snow.

When Coombs awoke an hour or so later, he couldn’t move. He tried to pick himself up from the snow, but the message from his mind didn’t reach his muscles. He lay there motionless for a few more seconds and then tried again. This time he was able to get up, but he was met with excruciating pain. Something was most definitely wrong. He needed to find a doctor.

After stepping back into his skis, Coombs wasn’t able to ski in his usual perfect form. Every turn sent agonizing pain down his spine and deep into the marrow of his bones. Instead of snowplowing down the mountain like a beginner and running the risk of being hit by a reckless skier, Coombs ducked the ropes to a trail called Bobby’s Run, a steep black diamond named after Bobby Kennedy that had been closed due to bad conditions. He painfully picked his way down through exposed rocks and grass, falling a few times before he finally reached the bottom. When Coombs’s mother entered the lodge, she found her son sitting unnaturally upright on the floor with his head and back pressed up against the wall. The look of distant worry in her son’s eyes was unmistakable. Again Coombs tried to pick himself up off the floor, but his body was frozen. Janet had to help her son to his feet.

“We took him over to the first-aid station. That particular Easter weekend, there was voluntary patrol, and this big Dr. Pierce from Mass General was on duty,” Janet Coombs remembered. “They took him right in for X-rays, and I was sitting there thinking that he just sprained his neck. But then the doctor came out and put his arm around me. When they do that, you know it’s not good.”

When Dr. Donald Pierce raised Coombs’s X-ray to the light, he couldn’t hide the shock on his face even after all his years working as an orthopedist. “It looked like you put a couple glass bottles in a plastic bag and smashed them all up. It was just shattered pieces all over the place,” described Bill Stepchew, who saw the X-ray later. “Nobody could understand how he could walk, let alone ski, with all those broken bones floating around.”

Coombs’s cervical vertebrae were fractured from C4 to C7, essentially from his Adam’s apple to his sternum. The X-ray revealed that one shard of bone, about the size and shape of a razor blade, pointed dangerously close to his spinal column. Dr. Pierce said that only Coombs’s thick, muscular neck was keeping all the bones in place, preventing paralysis. They immediately strapped him to a backboard and loaded him into an ambulance, which got lost on the way to Massachusetts General Hospital.

When Coombs finally arrived at the hospital, doctors discovered that he was also coming down with pneumonia. His broken neck desperately needed to be fused, but they couldn’t perform the surgery while he was sick. Coombs was strapped to a bed for a week until he recovered. “My folks lived at Mass General,” Coombs’s sister Nancy recalled. “My mom told me there were many dark days prior to his surgery. They didn’t know if he would even be able to walk again while they were waiting for the swelling and pneumonia to go away.”

Once Coombs overcame the pneumonia, Dr. Pierce took him directly into surgery. “The operation, I remember, was all day long, seemed like,” Janet Coombs said. “It was a nightmare.” Dr. Pierce made an eight-inch incision in the back of Coombs’s neck and then carefully spread each vertebra, removing the damaged disks and shaving away any bone spurs. He put the puzzle back together using steel rods and screws.

After the surgery, Coombs needed to be put in a halo brace to keep his head stationary and allow his fused vertebrae to heal. According to Janet Coombs, Dr. Pierce was the only physician at Mass General who could perform the halo brace procedure at the time, which had come into practice in 1959. Prior to that, spinal injuries were typically treated with bed traction, where the patient was strapped tightly to a bed for months on end. Horrible bedsores and muscle wasting led doctors to come up with a better treatment.

Enter the halo brace. Four titanium pins were drilled into the patient’s skull, two in the front and two in the back. The pins were then connected to a metal halo that circled the patient’s head and was linked to a fleece-lined chest brace. The whole rig looked like a torture device. Depending on the severity of the break, the patient remained in this uncomfortable contraption for a couple of weeks up to a couple of months. Although the halo brace was more humane than bed traction, the procedure itself seemed far more barbaric.

“They told Gordon and me to go as far away as we could because they were going to put this halo on Doug, which is horribly painful and you have to do it without [general] anesthesia,” Janet Coombs remembered. “They didn’t want us to see him or hear him screaming.” Dr. Pierce entered the room and, after a local anesthetic was administered, began by wrapping a measuring tape around Coombs’s head. He then made two marks with a felt-tip pen on his forehead. After Dr. Pierce did the same to the back of his scalp, Coombs was placed in the chest brace that he’d be stuck in for the next two months. They positioned the halo around his head. Picking up a surgical screwdriver, Dr. Pierce looked down at Coombs and told him to think of every curse word he knew.

When his parents entered his room after the procedure, Coombs was staring blankly up at the ceiling through the cage now screwed into his skull. It must have looked freakish to Janet and Gordon Coombs seeing it for the first time. With his head still throbbing from the screws and the vest pressing snuggly around his shoulders and chest, Coombs must have been feeling the full gravity of his situation setting in. The invincible Doug Coombs had been broken. The star athlete couldn’t run through the woods. He couldn’t climb trees. Worst of all, he couldn’t ski. Coombs turned to his father and told him to go home and burn his skis.

***

Coombs spent three weeks at Mass General recovering after his surgeries. “He was a terribly sick guy for about a week,” his mother remembered. “We hired special nurses to be with him around the clock for days. He was too sick to see anybody. All the kids from high school came and I couldn’t let them in.” The pain medication had its way with his system, and Coombs floated in and out of fever.

Once he pulled through, though, his boundless optimism fueled his recovery. First came sitting up in bed, and then standing a day or two later. “One morning we went in, and there he was on one of those exercise bikes in the hall,” his mother said.

“Did you burn my skis?” Coombs asked his father. Gordon shook his head. “Oh good!”

Coombs became the darling of every nurse on his floor and a favorite among his fellow patients, including his much-older roommate, who found him endlessly entertaining. He was a model patient, rarely complaining and always smiling through the metal cage.

As far as the doctors were concerned, Coombs was something of a miracle. “There were about twenty people in the severe neck ward, and he was the only one who had any chance of ever walking again,” Bill Stepchew said. “A lot of doctors wanted to come in and take a look at him because it was sort of astonishing that he survived the injury, let alone was able to function like that.”

After he was released from the hospital, Coombs was asked to return for more than just his regular checkups. As his mother remembered, “The doctor called and said, ‘Would you mind if Doug came in and talked to a lady who’s going to have the [halo procedure] done to her? Because she’s petrified.’ So Doug went in and held her hand and calmed her right down. He said, ‘Look at me, I’m walking around with the thing!’”

Back home on Wilson Road, Gordon Coombs fashioned a wooden ramp at the head of his son’s bed for the halo to lean against so he could sleep. The metal contraption made even the simplest task a complete hassle. People stared at him wherever he went. “It was really tough because he wore that halo into the summer,” remembered his sister. “The halo was attached to a heavy vest, and he was sweating all the time.”

If Coombs was a big man on his high school campus before the crash, he was a giant after it. His metal halo loomed high over the rest of the student body like the exposed beams of a new skyscraper. He regaled his buddies with grisly play-by-play details of his accident, each telling more graphic and elaborate than the last.

“Doug was the king of exaggeration,” remembered Frank Silva. “We called it the Coombs factor.” By the time Coombs got done telling a tale, inches of snow magically turned into feet, mile walks became marathons. The story of his broken neck was no different. One version included him popping a bottle of champagne with the ambulance driver on the way to the hospital. In another, Coombs claimed to have knocked out a pesky medical intern who kept pricking his legs with needles to make sure he wasn’t paralyzed. When the screws in his halo came loose one day, Coombs walked out of school and into the office of a local doctor. The doctor peered for a while at the contraption, then fetched his toolbox and a screwdriver from the trunk of his car. The last story, Janet Coombs confirmed, was true. Fact or fiction, it didn’t matter to his buddies. They lapped it up all the same.

It didn’t take long for skiing to reenter Coombs’s mind. “Even when he had the halo on, he used to stand in the living room with his skis on,” said Nancy Coombs. “He missed his skiing so much.” Coombs did everything he could to maintain the strength in his legs, walking everywhere and performing wall squats for five minutes at a time. When he devised a way to slip a backpack over the halo, he returned to the White Mountains and hiked the days away.

When the halo finally came off, the mobility in Coombs’s neck was extremely limited. Dr. Pierce had effectively turned four of his cervical vertebra into one long bone held together by screws and steel rods. To look in any direction, Coombs had to shift his entire upper body. He couldn’t tilt his head to look up. This severe immobility would remain with him for rest of his life.

The more serious prognosis was that another bad fall might not just paralyze Coombs—it could kill him. The jostling associated with skiing could dislodge the hardware and cause damage to his spinal column. Worst of all, the location of the fusion rendered him extremely vulnerable. The major danger zone wasn’t necessarily his fused vertebrae, but rather the C3 vertebra, which hadn’t been broken in the crash but was now sandwiched between the steel and his skull. The slightest fall could snap it.

At sixteen years old, Doug Coombs had a decision to make. He could follow the doctor’s orders and live a safe and sedentary life, one that would keep his fused neck intact and keep him alive. Or he could choose to follow his passion and ski again, even if that meant running the risk of being killed by the slightest fall. For Coombs the answer was obvious. As one of his childhood friends recalled, “I asked him once that year, his junior year of high school, ‘Doug, do you think this will slow you down some?’ He said, ‘No way, I’ll be the same.’ I said, ‘How do you know that?’ And he said, ‘Because I’m Doug Coombs.’”

Author Robert Cocuzzo is touring New England for multimedia author events this fall. For a list of events or if you’d like to host, visit trackingthewildcoomba.com.

To purchase the book visit Amazon.com

Robert Cocuzzo is the editor of N Magazine, a lifestyle publication based on the island of Nantucket. He also writes for a number of other publications, and splits his time between the island of Nantucket, Boston, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire.