Bringing Kosti Home

After Kosti Ruohomaa died in 1961, his legacy as one of New England’s greatest photographers was all but forgotten. Now his photos have a new life.

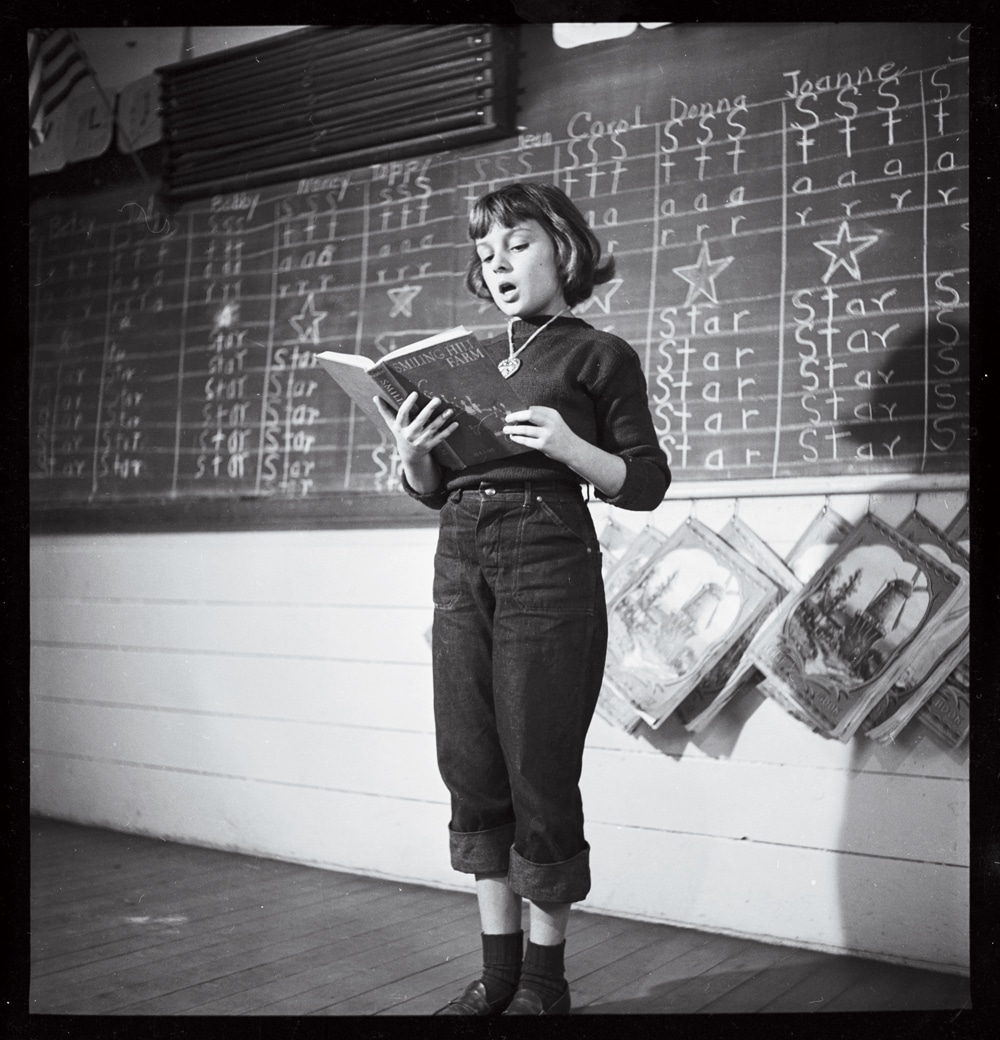

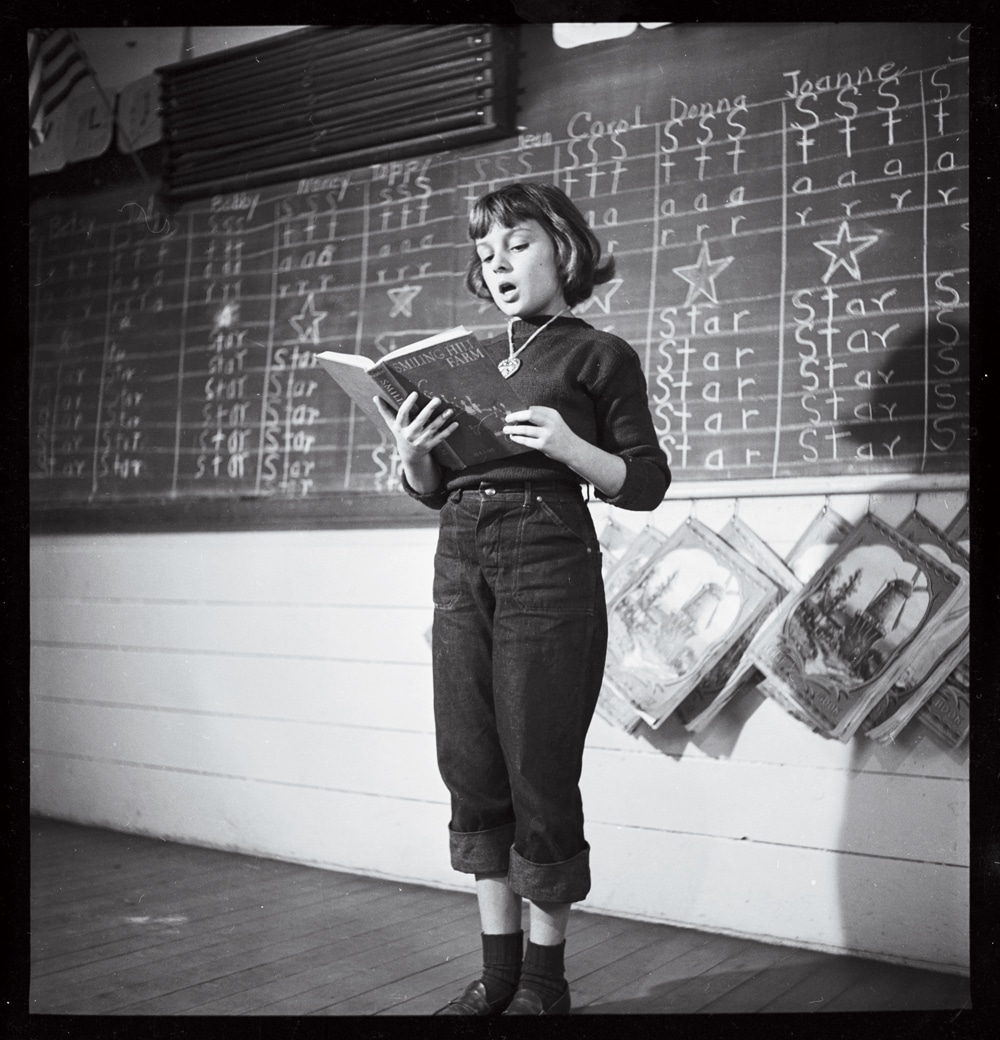

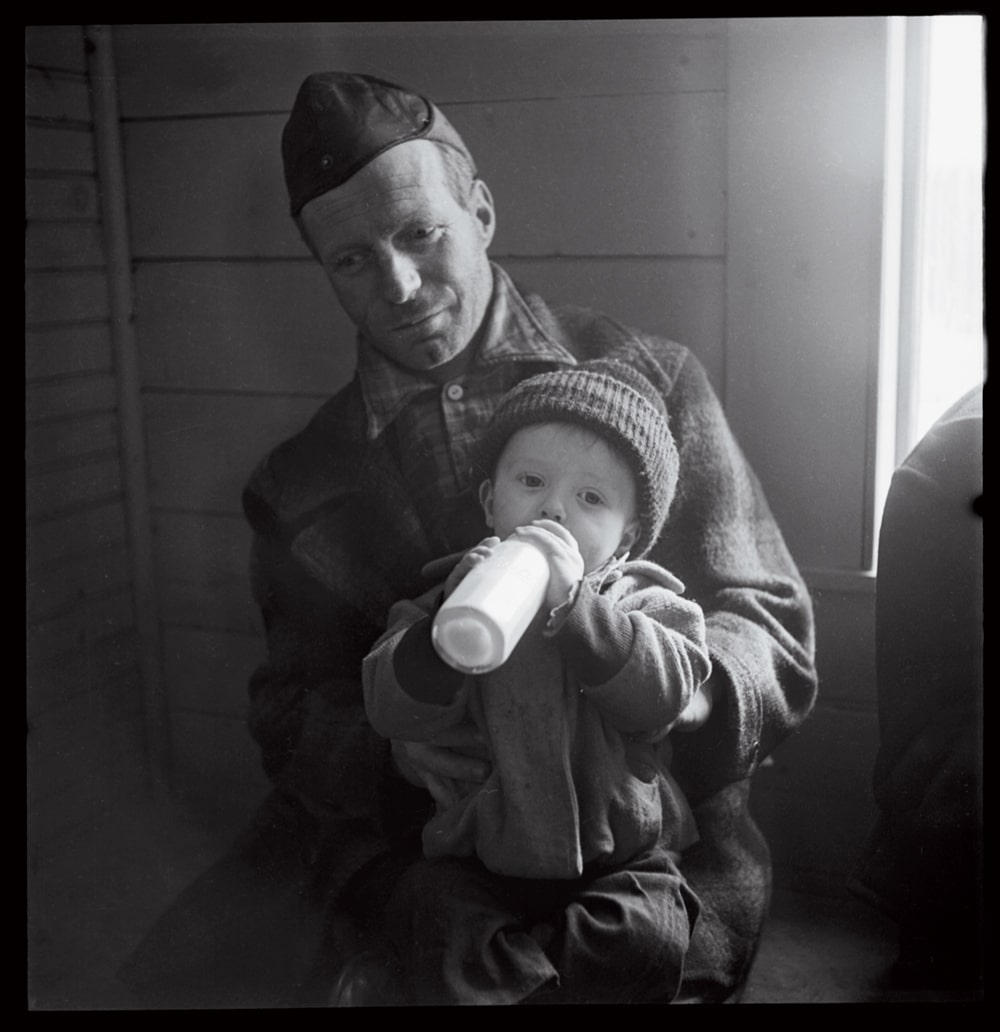

Many of Ruohomaa’s self-assignments centered on everyday life in midcoast Maine, such as this student reading aloud in a one-room schoolhouse in Rockville in 1950.

One day in October 2017, Kevin Johnson, photo archivist at the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, arrived at a warehouse in Fort Lee, New Jersey. His mission: to resurrect a legend. Within 30 minutes he had loaded his SUV with seven two-foot-long boxes crammed with manila envelopes containing negatives, contact sheets, and notes. Each envelope was the result of a photo assignment (about 1,200 total)—the life’s work of Maine photographer Kosti Ruohomaa, who died in 1961 at age 47. Over the years, Ruohomaa’s name had been all but forgotten, except among a small cadre of photographers who after discovering Night Train at Wiscasset Station, a collection of his photographs published in 1977, would say his work had inspired them. Hours after leaving the warehouse, as Johnson crossed the New Hampshire border into Maine he stopped at a sign reading: “Welcome to Maine.” He then photographed the boxes to document the moment when, he says, “Kosti finally came home.”

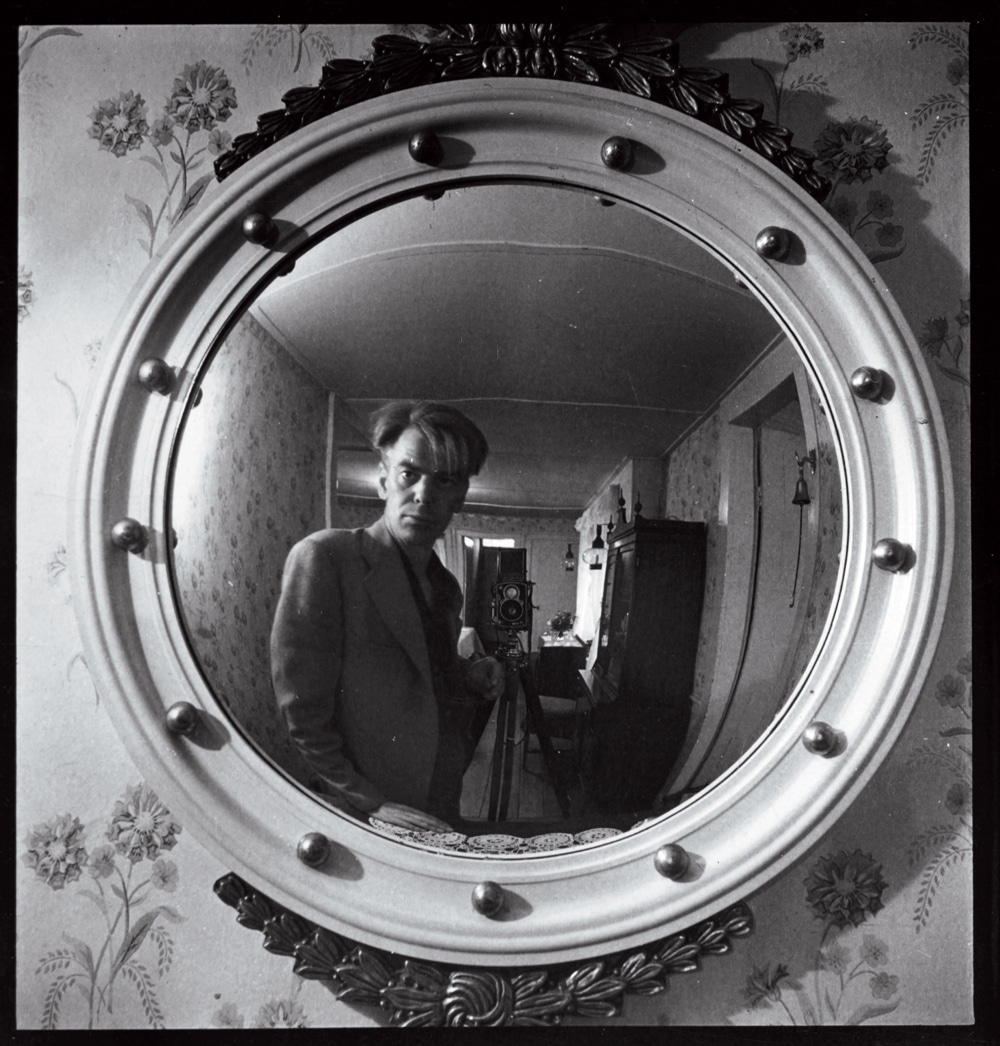

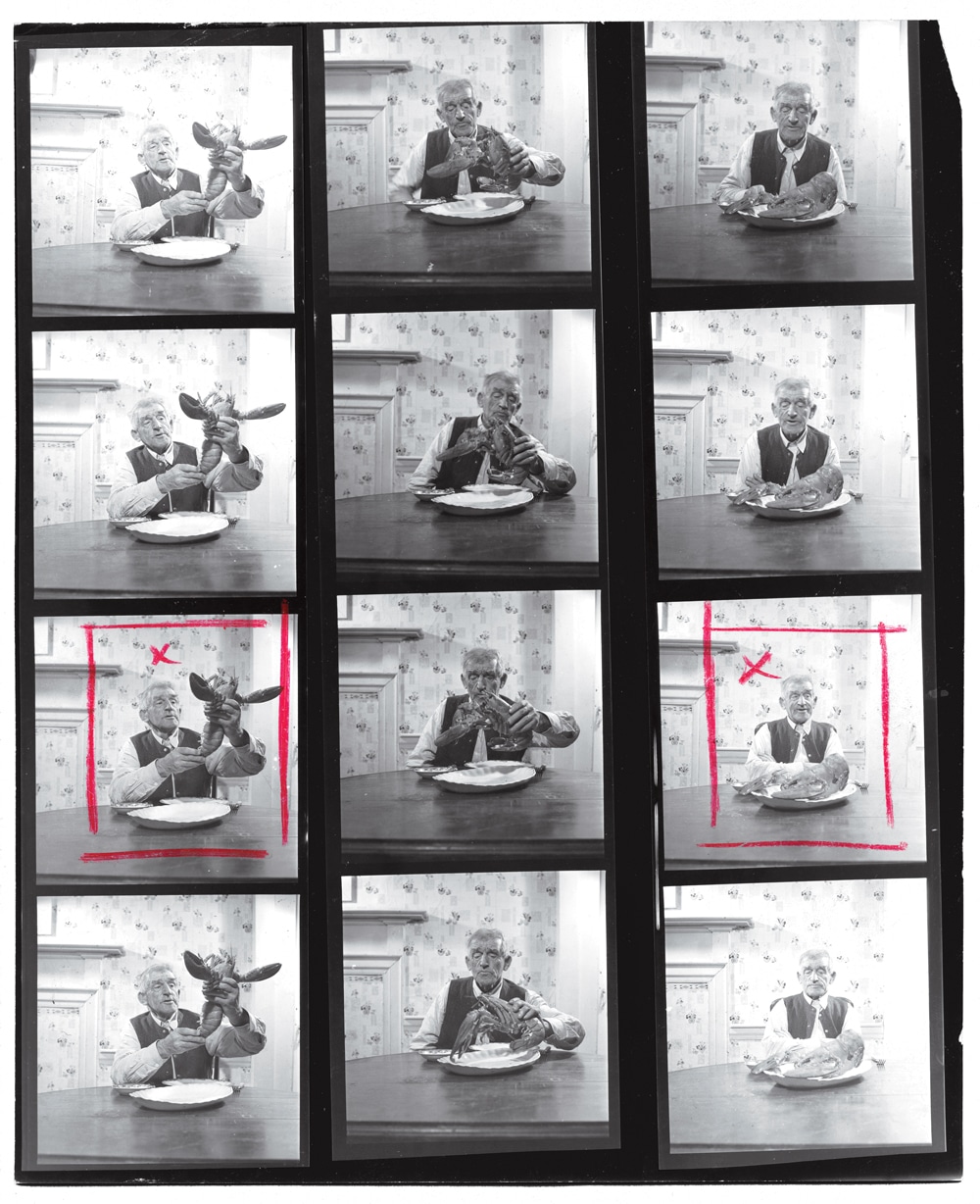

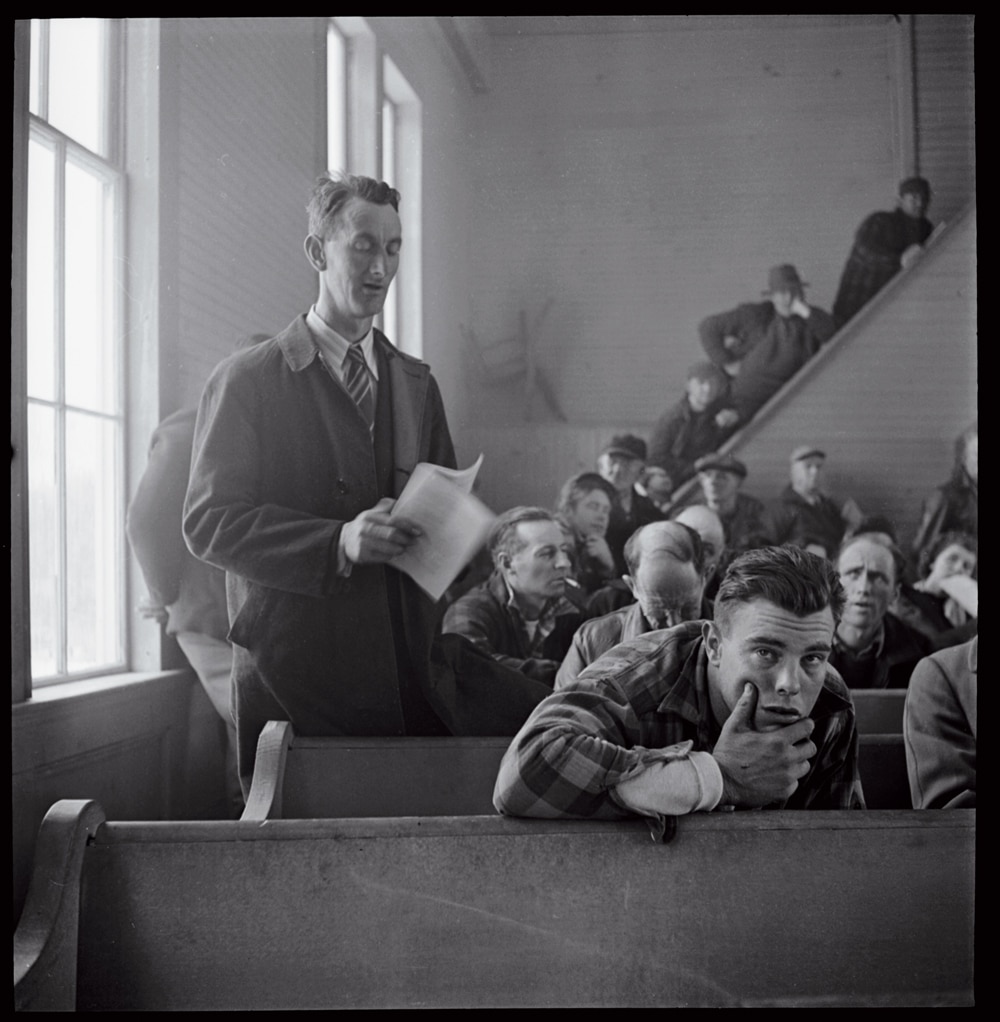

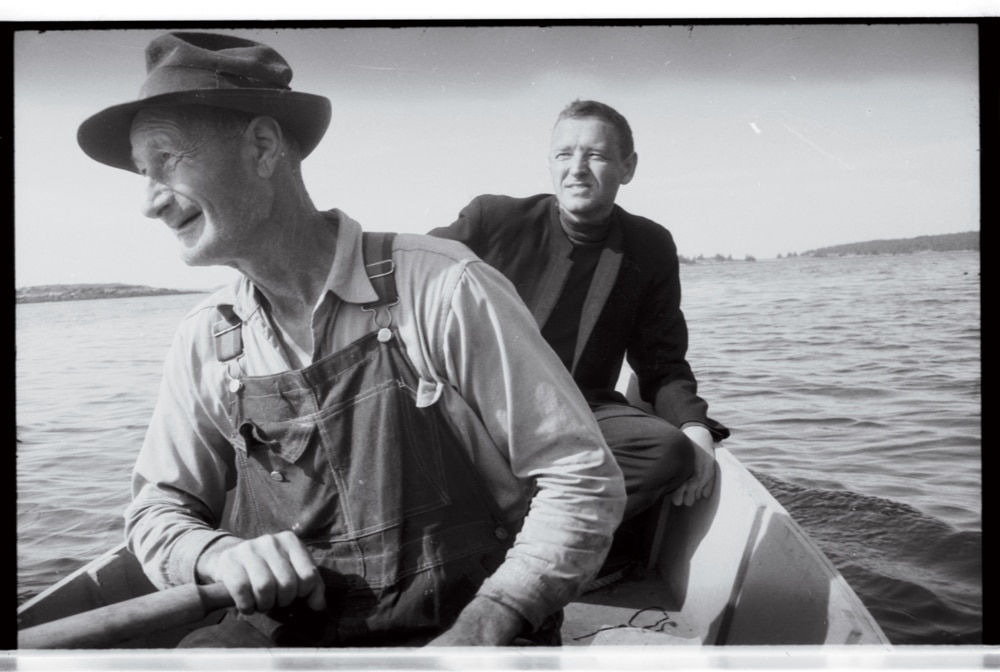

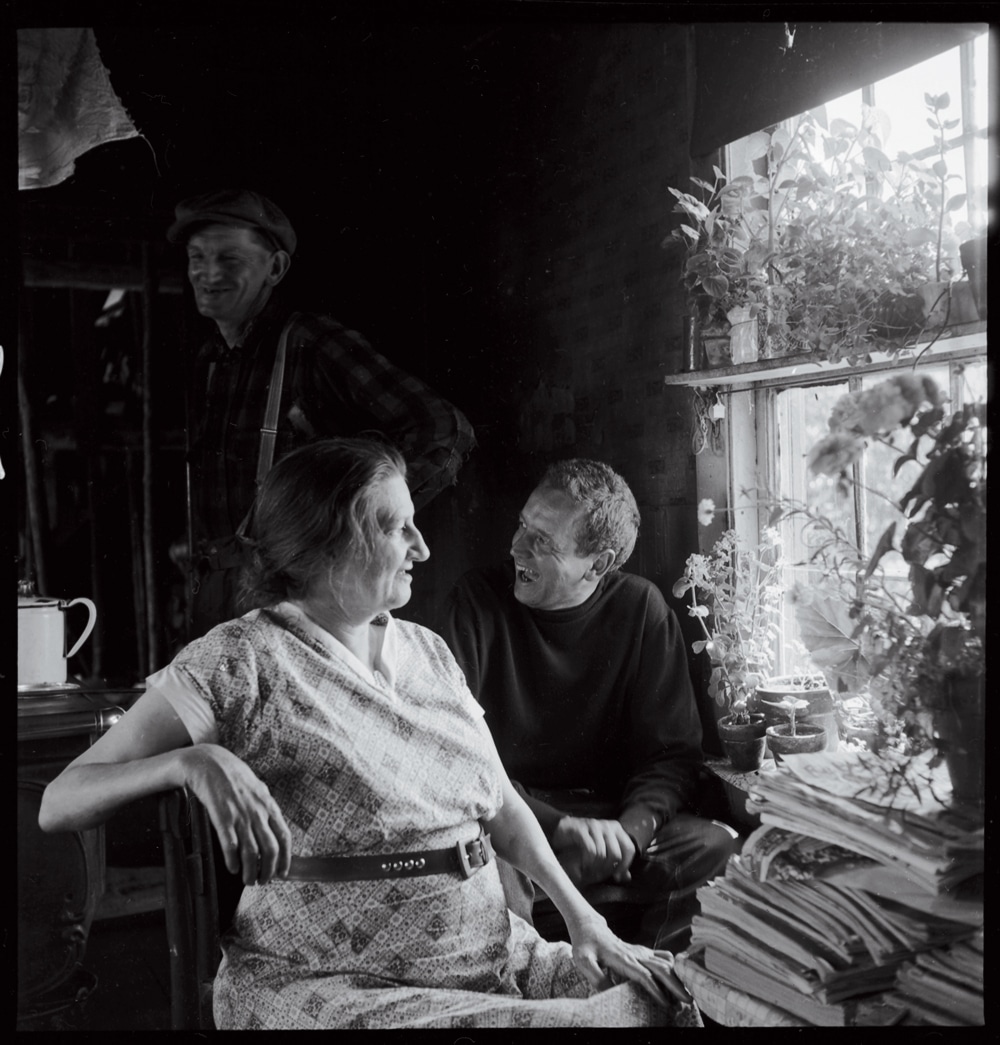

A year later, I visit Johnson in an upstairs room at the museum to look at a small fraction of the collection. Deanna Bonner-Ganter joins us. A former Maine State Museum curator, she has devoted 30 years to researching Ruohomaa’s life (he supposedly told Andrew Wyeth to “say it like row-home-aboat”). Her 2016 biography, Kosti Ruohomaa: The Photographer Poet, chronicles how he became one of the top names at the famed Black Star photo agency in the ’40s and ’50s. His images of rural New England and its people—mostly Mainers—graced the pages of the nation’s most famous magazines. The way the world viewed Maine at that time was partly influenced by what Ruohomaa showed them. He wrote that he found his Maine “hidden in the offbeat nooks and crannies.” The expression of what he felt for his home region was compared to what Ansel Adams portrayed in the West.

There may be as many as 50,000 images inside these boxes, all waiting to be catalogued, and eventually scanned and digitized, then placed on the museum’s website for the public’s viewing. It’s an ambitious and daunting endeavor. Bonner-Ganter volunteers at least 15 hours a week to help make it happen.

Photo Credit : Photo courtesy of Penobscot Marine Museum

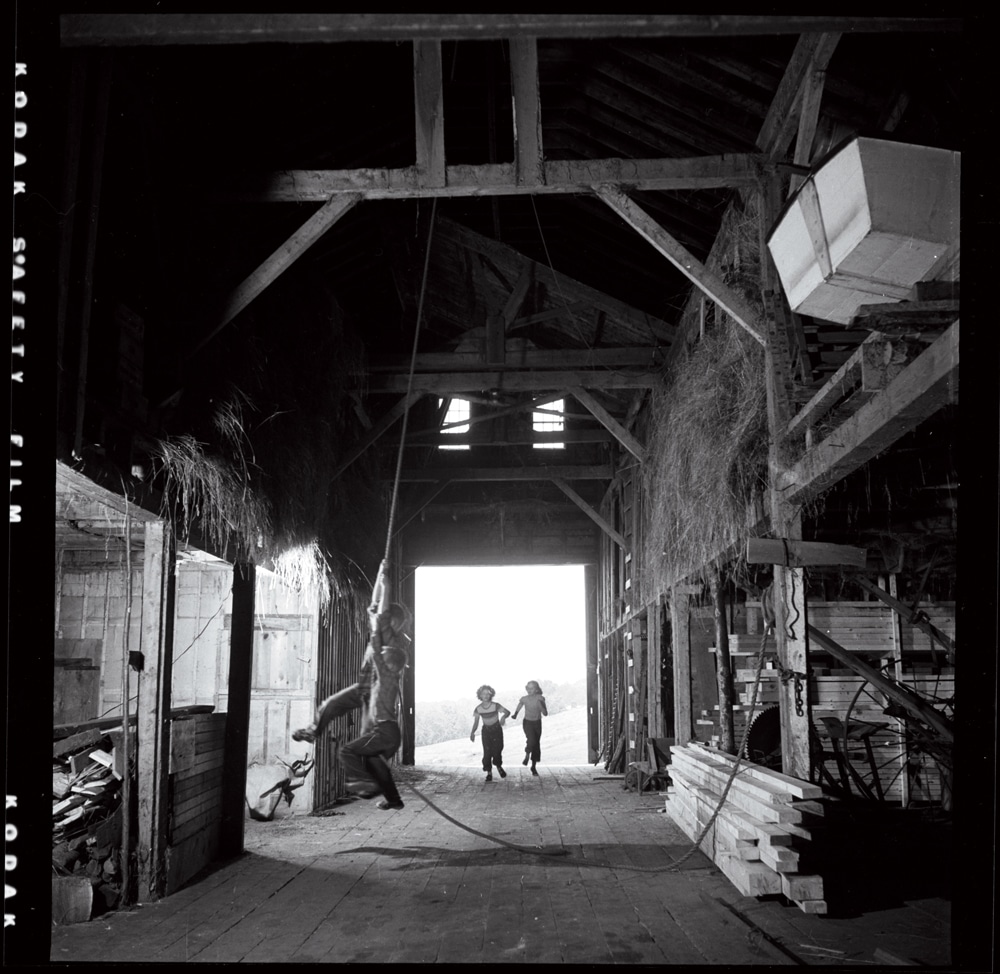

As we open one of the manila envelopes, Johnson says, “I’ve seen maybe only 10 percent of what we have. There are surprises all the time.” Spilling out on a table are images of a river drive carrying timber from the North Woods to paper mills; workers on the family blueberry farm where Ruohomaa grew up, in Rockland, Maine; an island in winter, cold and harsh and strangely beautiful in black and white. “In the summer it is a bit too idealistically beautiful,” Ruohomaa once wrote of photographing Monhegan Island. “In the winter it has guts and drama and doesn’t wear such a pretty face. Anyway, it has the kind of meat my camera likes.”

Ruohomaa was racing time. Alcoholism was eroding his health, and, as Johnson says, “he knew the way the world was evolving, many things would not be around.” After he died, Black Star retained the rights to his work. For decades, it was as though his photographs had been buried with him. When the agency moved its headquarters, his photos landed in the New Jersey warehouse, where they might have languished for years, unseen. But Ruohomaa’s passion was matched by that of Johnson and Bonner-Ganter, who struck a deal with Black Star: The Penobscot Marine Museum would care for the work and return it to the public eye, while the agency would hold publishing rights.

There have already been two exhibits from what arrived in Maine from the warehouse. Johnson thinks they will need $350,000 and three more years to bring Ruohomaa’s world online. A patron has already pledged $100,000, and grants are being pursued. After spending a day with Johnson and Bonner-Ganter, I left thinking about how we often take museums for granted, when at their core they represent labors of love, and sometimes they serve to remind us of what we do not even know we have forgotten. —Mel Allen

To learn more, go to penobscotmarinemuseum.org. The museum’s exhibits are closed until May, but its offices, research libraries, and archives are open year-round.

All photographs from the Kosti Ruohomaa Collection at the Penobscot Marine Museum, Searsport, ME. Courtesy of Black Star, White Plains, NY.

SEE MORE: Kosti Ruohomaa | Additional Photos

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen