Two Voices, One Message | Our Land, Our Sea, Our Future

The ProphetGeorge Perkins Marsh by Leath Tonino You know Henry David Thoreau and you know John Muir and you know Teddy Roosevelt. You probably have heard of Aldo Leopold (A Sand County Almanac), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring), and Edward Abbey (Desert Solitaire). These are the famous nature lovers of American history, the writer-thinker-preachers we credit […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe Prophet

George Perkins Marsh

by Leath Tonino

You know Henry David Thoreau and you know John Muir and you know Teddy Roosevelt. You probably have heard of Aldo Leopold (A Sand County Almanac), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring), and Edward Abbey (Desert Solitaire). These are the famous nature lovers of American history, the writer-thinker-preachers we credit with opening our collective mind to the glories of the wild. Dirt under their nails, wind in their hair, they taught us to go slow, to listen close, to wander and wonder and respect and protect and defend and cherish. We heap praise upon them, and rightly so. But what of Vermont’s George Perkins Marsh, born in 1801? Do you know his name?

Photo Credit : Library of Congress

Few people do. Outside of that green tribe composed of environmental historians, eco-philosophers, professional conservationists, and rangers at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, he doesn’t get much play. Within that tribe, though, he’s a prophet, a sage; his book Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action a kind of bible.

Like any good book, Man and Nature comes loaded with blurbs of praise, in this case provided by famous conservationists a century or more after it was first published in 1864:

“The fountainhead of the conservation movement.” —Lewis Mumford

“Epoch-making.” —Gifford Pinchot

“The beginning of land wisdom in this country.” —Stewart Udall

“The rudest kick in the face that American initiative, optimism, and carelessness had yet received.” —Wallace Stegner

Marsh’s biographer, David Lowenthal, ranks Man and Nature as “the most influential text of its time next to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published just five years earlier.” In his introduction to a 2003 reprint, he summarizes the book’s core argument: “Humans depend upon soil, plants, and animals. But exploiting them deranges and may devastate the whole supporting fabric of nature. To forestall such damage we need to learn how nature works and how we affect it. And then we must act in concert to retrieve a more viable world.” The word ecology wasn’t coined until 1866, two years after Man and Nature came out—but yes, ecological collapse is precisely what’s at stake.

—George Perkins Marsh, 1847

Photo Credit : Library of Congress

Marsh writes in sterner terms than his biographer, which is part of the fun of his book. A bespectacled polymath with a pudgy face, a round belly, and a thick beard best described as bearlike (black bear in the middle of his life, polar bear near the end), he warns the still-young American republic that “human crime and human improvidence” might reduce the earth “to such a condition of impoverished productiveness, of shattered surface, of climatic excess, as to threaten the deprivation, barbarism, and perhaps even extinction of the species.” He uses the metaphor of a house: We are tearing apart the dwelling we live in, ripping out the floors and doors and window frames to fuel the fire of our wants and needs. And get this: The house can’t be easily rebuilt. “Marsh was the first to recognize that man’s environmental impacts were not only enormous and fearsome, but even cataclysmic and irreversible,” writes Lowenthal. The book’s proposed title, rejected by its publisher, was Man the Disturber of Nature’s Harmonies.

Does any of this sound radical? Is it ear-catching, head-turning talk? By today’s standards—what with every magazine article and TV report pushing doomsday scenarios in which runaway development, fossil fuel consumption, and population growth (to name a few) spell the end of rain forests, shoreline cities, and potable water (to name a few)—no, this is hardly big news. But try to imagine encountering Man and Nature, all 560 vehement, erudite pages of it, at the time of its publication. The website for the George Perkins Marsh Institute at Clark University offers some context: “The conventional idea held by geographers of the day, Arnold Guyot and Carl Ritter, was that the physical aspect of the earth was entirely the result of natural phenomena, mountains, rivers, oceans.” In other words, humans were one thing, nature something else, and the former had no impact on the latter.

Lowenthal describes the middle of the 19th century as “the peak of Western resource optimism” and says, quite poetically, that New England’s pioneers were caught up in “the myth of limitless plenty.” Between 1791 and the War of 1812, Vermont was the fastest-growing state in the Union. By the 1850s it was almost entirely deforested, much of the lumber going to produce potash and charcoal that provided a cash bonus for the hardscrabble hill farmers doing the cutting. Come 1860, 42 percent of native-born Vermonters had “out-migrated” to places like the Ohio Valley—to the promise of Beyond and the assured abundance of Elsewhere.

Hindsight being what it is, we now can see how all the dots connect to form a line that sprints straight off a cliff. We can see the axes glinting and the trees falling, the naked earth crumbling, the rainstorms tearing steep slopes to pieces. We can see the sediments clotting the rivers; the fish floating dead in pale-bellied rafts; the beaver, bear, moose, and deer flickering out like ghosts. We can see thousands of sheep grazing gullied pastures, chewing up the ground with their teeth and hooves. And we can see the men—earnest, industrious, well intentioned, and ignorant—their heads lowered to the task of unwittingly ruining the land. The tall grass prairie of Iowa was all but plowed under by 1876; the American bison an inch from extinction in 1890.

“Sight is a faculty,” Marsh writes in Man and Nature, “seeing, an art.”

How a country boy from little old Vermont grew up to re-envision his culture’s destructive attitudes and practices is a story full of improbable, almost-too-perfect alignments. It begins in 1808 with a 7-year-old George Perkins Marsh hunched over an encyclopedia in a dim room in his family’s home in Woodstock. He’s a voracious reader, and having spent a week straight squinting at the pages, he finds that the words are at last blurring away. His father, a wealthy lawyer, forbids further study, ordering his nearly blind son outside to heal in the light.

It takes many days for young George’s eyesight to come back, and when it does it’s as though he’s seeing the natural world for the first time. An “interminable forest” rolls away in all directions, its leafy canopy trembling in soft wind. He hikes. He roams. He learns the word watershed, learns the ridges and valleys, the forces that shaped them, the rhyme and reason of the earth beneath his feet. According to the documentary A Place in the Land, “the plants and animals were persons [to him], not things.” He spent his early life “almost literally in the woods,” Marsh will remember years later, fondly.

But the glinting axes, well, you know what the glinting axes do. When at age 15 he heads off to Dartmouth College, his home is fast becoming a scrapeland, a scabland, a scarland. The year is 1816, the beating heart of the boom time. Mount Tom stands behind the family’s house, a lump in a mosaic of stumps and rocky ledges. The Ottauquechee River floods its banks, heavy and brown, sanding over the meadows. These images go inside Marsh and grab hold of something deep, never to let go.

After graduation, Marsh’s accomplishments pile up to form a sort of Renaissance man’s résumé. A lawyer by training, he serves as Vermont railroad commissioner, fish commissioner, and State House commissioner and is elected to four terms as representative in Washington, D.C. (where he helps create the Smithsonian Institution and aids in the Washington Monument redesign). Fluent in 20 languages, he’s respected around the world as a premier linguist, translating German verse, Danish law, and Swedish fiction. Yet he remains a down-to-earth, practical-as-ever Yankee, dabbling in marble quarrying, woolen manufacturing, and farming. As Lowenthal puts it, Marsh’s “omnicompetence was legendary.”

And now things really get interesting. Appointed American envoy to Turkey in 1849, Marsh tours Egypt, Palestine, Central Europe, and Italy, taking note, often from atop a camel, of fallen cities, worn-out river valleys, and strange deserts where human and natural histories entwine. The overload of new information sends him rushing—where else?—to the great libraries of antiquity. “Only because he could read so many languages and explore so many ancient texts at first hand,” writes William Cronon of the University of Wisconsin, “was Marsh able to gather the widely scattered evidence for his argument that the ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean had brought about their own collapse by their abuse of the environment.”

The fall of Rome, it turns out, was an issue of resource depletion and improper land management—it was the myth of limitless plenty getting the best of an entire civilization. Marsh thinks back to his childhood, to the axes, to the denuded ridges. Through his insight, the ambassador from Vermont “built a bridge between these two points of his own lived experience,” Cronon says. “In the degraded environments of the Mediterranean he saw a prophecy of America’s possible future.”

It’s a light-bulb epiphany, an illumination of connections heretofore unseen, and over the years it will only grow brighter. When Marsh starts work on Man and Nature in 1860, his eyes are still weak from the early battle with the encyclopedia, but his vision—his vision—is sharp.

That vision—the vision that went on to inspire conservation reforms in India, Australia, South Africa, and Japan, not to mention everything from the creation of the U.S. Forest Service to the rise of the environmental movement in the United States—it has a home. At 643 acres, the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park in Woodstock is considerably less grand than, say, the Grand Canyon, but the terrain is stunning in its own mossy, ferny, Green Mountain way. On the flanks of Mount Tom, paths and dirt lanes wind through stands of sugar maples, red pines, and hemlocks, the clear-cuts that once wrecked the surrounding countryside now visible only in a hiker’s imagination. Opened in 1998, Vermont’s sole national park is unique among the 417 units in the federal system because of its mission statement: to tell the story of conservation history and the evolving nature of land stewardship in America. Yosemite has its soaring granite domes, Yellowstone its howling wolves. Woodstock has its local boy and his big book.

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

When I visited the Carriage Barn Visitor Center—a warm, woody museum-library boasting 1,000 titles, comfortable chairs, and an environmental history display that runs from Ralph Waldo Emerson through Earth Day and beyond—I was greeted by Joe Herrick, his white hair just visible beneath a classic flat-brimmed park ranger hat. “What are you doing out there, building an ark?” he asked. It had been raining for three days, all across Vermont, and it showed no sign of stopping. I mentioned an exuberant gang of second-graders I’d encountered in the parking lot, their boldly colored slickers lending a welcome flair to the otherwise gray day. “I think of them as bees, and those yellow buses are the hives,” Herrick said. “Hundreds of groups buzz through every year.”

The comment made me smile, and not only because of the affection in Herrick’s voice. Here was an indication that the so-called “grandfather of conservation” might not be quite as obscure as I had thought. Marsh’s life was written across the room’s walls, bound in books lining the shelves, framed in black-and-white photos. One photo showed Woodstock in 1869, all bony pastures and bare hills; another showed a white-bearded Marsh working on the third edition of Man and Nature at a sprawling desk, papers spread here and there, a marble statue of some armless lady peering over his shoulder. Quotes were collaged with the images—excerpts from letters Marsh had written to friends, lines from lectures he’d presented to colleagues. In this welcoming space, so snug and cozy on a dim morning, Man and Nature was not a dead tome but a living presence, its message of balance and interdependence speaking across the ages.

Much has changed since 1864, both for better and for worse, but when looked at from another angle, nothing much has changed. We talk about mass extinctions, global warming, and greedy corporate polluters as if these are new terrors, new problems. But maybe they’re better understood as symptoms of some deeper, older problem. Maybe the real problem is no different from the one that a 19th-century Vermonter faced in his time, and the Romans faced in theirs, and today’s children will face 30 or 50 years down the line: We members of Homo sapiens have a mighty power, a power to destroy and to heal. We must restrain ourselves, must act as friends and helpers of the greater natural whole. It isn’t easy, and it never will be. Things run amok. In Marsh’s words, “Man has a right to the use, not the abuse, of the products of nature.”

I got out my wallet to pay the entrance fee, happy to contribute a few dollars. Herrick shook his head. “No charge,” he said. “You’re free to walk or read. It’s your park.” He tipped the brim of his hat, releasing a few beads of water to the floor.

Mount Tom was calling, misty and enchanted, and I was eager to stroll the land that both figuratively and literally opened George Perkins Marsh’s eyes. Heading for the door, I flipped up my raincoat’s hood. I assumed I’d meet the kids somewhere on the trail, downpour be damned.

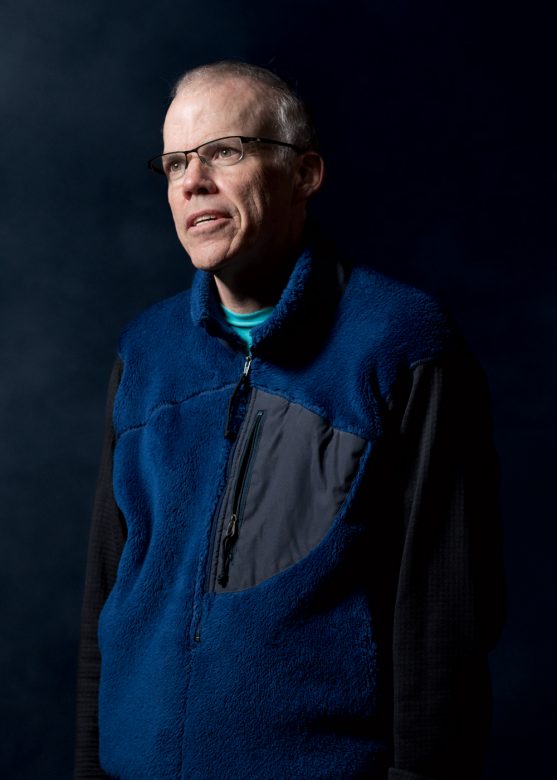

The Sentinel

Bill McKibben

by Richard Conniff

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

It’s a mid-September afternoon, and Bill McKibben—author, climate change activist, nemesis of the fossil fuel industry, cross-country skiing addict, devotee of small-town New England life, and drinker of local beers, in more or less that order—is at the wheel of his electric-blue plug-in hybrid, heading north out of Providence.

He and his wife, writer Sue Halpern, have been away from their home in the Green Mountains outside Middlebury overnight, on a trip to promote his first novel, Radio Free Vermont. It’s a funny book, and McKibben is not known for funny books. Well, it’s funny unless you happen to be a Walmart manager: McKibben starts his fable with small-town renegades flooding a new Walmart store knee-deep with the contents of the local sewer system. (Oh, come on, that’s funny.) And it’s funny unless you think there is something deeply alarming about Vermont seceding from the bigness and manifold badness of the United States at large. McKibben says the independent Republic of Vermont is just a plot device, not a movement. But his passion for his home state is genuine. As he hits the on-ramp out of Providence, he is almost quavering in anticipation of getting back.

McKibben is, of course, better known for books that are genuinely alarming. Climate change is his subject, both as an author and an activist. Fellow climate journalist Andrew Revkin describes him as “the ultimate endurance athlete of climate campaigning.” In a series of books and articles beginning with The End of Nature in 1989, McKibben has meticulously laid out the evidence that the rapid accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, from our massive burning of fossil fuels, is destroying the world as we once knew it. “The basic issue of the planet right now,” he told Revkin in a recent interview, “is that it’s disintegrating.” He refers to “my last grim book,” as if grim books were a genre, and has described his life after The End of Nature as 25 years of “sadness” and of “looking for ways out, for places that work.”

For McKibben, Vermont is one such place. Even in his grim books, he writes yearningly, sentimentally, about the maple cream cookies that a neighbor brings to the annual town meeting, about stopping to visit “the farm of the six Dutch brothers,” about “the sun shining through the winter-bare ridge at dusk,” and about the consoling mantra of local names—Camel’s Hump, Bread Loaf Mountain, Otter Creek—with which he lulls himself to sleep while on the road. The mountainous country around Lake Champlain, he writes, is “the landscape that fits with jigsaw precision into the hole in my heart.”

Vermont is also, however, what transformed him from author to activist and led him reluctantly to spend much of his life away from home. The turning point, he says as he heads north on 95 across Massachusetts, was a five-day protest march for climate action, from his hometown of Ripton to Burlington, in 2006. “We slept in fields,” he recalls, and had potluck suppers at Methodist churches along the way, “potluck suppers being their sacrament.”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

He meant the protest to be a one-time thing, “but when I got to Burlington, 1,000 people were marching with us, and in Vermont, 1,000 people is a lot of people,” he says. “But what was amazing was to read the story in the paper the next day.” It was 17 years after The End of Nature, and nine years after passage of the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement on climate change. An overwhelming abundance of scientific evidence had demonstrated the reality of climate change and the human role in causing it. And yet a newspaper story was describing 1,000 people walking across Vermont as the largest U.S. demonstration ever against climate change. It dawned on McKibben that writing books and making meticulous arguments wasn’t enough.

“It was blindingly obvious that we had all the things you need for a movement,” says McKibben. “We had the scientists, the policy people, the concerned citizens—everything except the movement. So it was clear that we needed to do it, and we needed to do it around the world.” Together with a small band of students at Middlebury College, where he was a scholar in residence, McKibben went on to found 350.org. They took the name from the maximum carbon dioxide concentration, in parts per million, that scientists say the atmosphere can handle without spinning the planet into chaos. (The CO² concentration today is somewhere above 400 parts per million, up from 280 in the preindustrial era, and as it rises, chaos has become our daily news, in the form of droughts, floods, wildfires, rapidly warming oceans, and back-to-back Category 5 hurricanes.)

Photo Credit : Kristian Buus/Alamy Stock Photo

The walk across Vermont also taught McKibben the value of shaping protests, even using “smoke and mirrors,” he says, to achieve an impact beyond mere numbers. “We did 1,000 people in Vermont. If we had done 5,000 people in New York City, it would have been worse than doing nothing.” So for its first effort, 350.org orchestrated 5,200 simultaneous demonstrations around the world. Some of them attracted as few as 10 people, others thousands, but the global synchrony of the effort made it news everywhere, and CNN later quoted the organizers calling it “the most widespread day of environmental action in the planet’s history.”

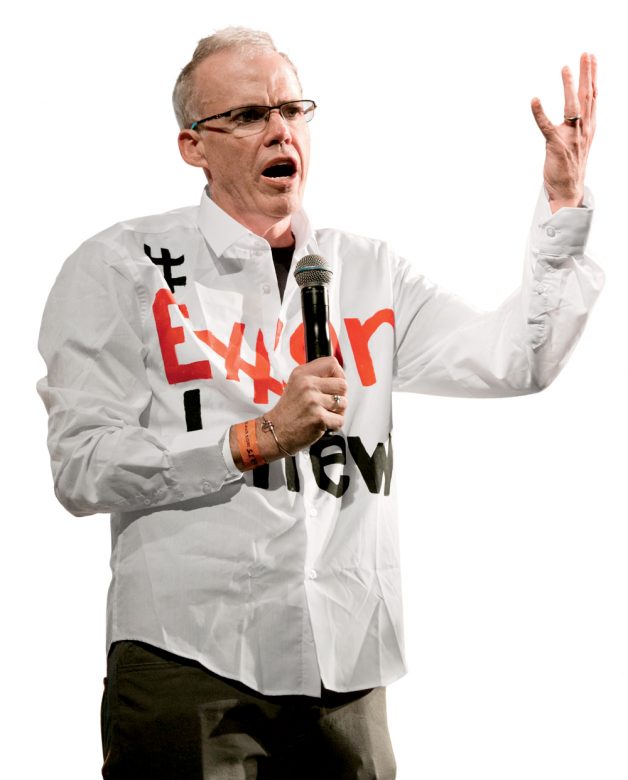

Creative protest became McKibben’s new specialty. Among other events, he led thousands of people in forming a human chain around the White House in 2011, to persuade President Barack Obama to block the Keystone XL pipeline. McKibben was arrested, along with 1,252 other protesters, in “the biggest civil disobedience action” in decades, he writes. When he got around to organizing a climate march in New York City, in 2014, it attracted not 5,000 people but more than 300,000—plus hundreds of thousands more in simultaneous protests in 156 countries around the world.

Now 57, McKibben has become the public face of the climate movement worldwide. At 6 foot 2 and 180 pounds, with a slight scholar-athlete hunch, he does not look the part of the political firebrand. His hair has receded to a few close-cropped islands of gray above a high, narrow forehead; deep-set eyes; and a long, slightly protuberant upper lip, the mouth habitually drawn down at the corners. It is the haunted face of a Norwegian minister who cannot quite get eternal damnation out of his mind.

But McKibben is also capable of making the odd quip on our path to hell, and he has proved to be an adept public speaker—deeply informed, entertaining, and unflappable. During McKibben’s 2011 appearance on The Colbert Report, host Stephen Colbert, in his right-wing-pundit persona, asked him, “You’re from Vermont? Did you ride your bicycle down here? Did you drive an oxcart down here? How’d you get down here? Do you have a vehicle that runs on hypocrisy?” Smiling, McKibben replied, “There is no doubt that I am a hypocrite,” and then added his hope that the work of organizing a global movement against climate change would ultimately repay the necessity of “spewing carbon behind me as I went.”

Inevitably, McKibben’s car runs, like most of our cars, mainly on gas, albeit with a little boost from electricity, and the first stop north of Providence is a gas station in Lexington, Massachusetts. This also gives McKibben a chance to explain the origins of his belief in the value of resistance. He grew up in this town, around its battle green, where local militia in April 1775 first stood up to British troops. In high school, McKibben passed a history test that allowed him to serve as a licensed guide for tourists, holding out his tricorn hat afterward for tips.

“I told the story of the American Revolution hundreds of times,” he says. He points out the statue of John Parker, commander of the local militia, and repeats the passionate cry attributed to him, “If they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” The British won the first victory of the Revolutionary War in Lexington, killing eight local men, McKibben recounts, and then marched on to Concord, where “they suffered the first defeat.” He seems most engaged by the British retreat back through Lexington, “where the Americans first figured out guerrilla warfare. The British thought it was very unsporting.” The lesson he took away, he says, was “that ordinary citizens were supposed to play a role in the political and civic life of the nation.” A taste for guerrilla tactics may also have adhered.

In 1971, when McKibben was just 10 years old, John Kerry led a Vietnam Veterans Against the War contingent to town, staging “guerrilla theater” antiwar events en route from Concord to Boston. But Lexington’s selectmen, “who were more conservative than the people,” says McKibben, ordered the veterans to come into town single file and denied them permission to camp on the battle green. McKibben’s father, a business journalist, was one of the sympathetic townspeople who went out to join the veterans on the green that night. “All 500 were arrested, taken to the DPW garage, held till 4 a.m., and had to pay a $5 fine,” McKibben recalls. “They were home by breakfast—but it made a big impression on me.”

350.org have helped organize a number of Keystone XL protests in Washington, D.C.

Photo Credit : Ken Cedeno/Corbis via Getty Images

He turns the corner and points to the offices of the Lexington Minuteman, where he began his career as a writer. In junior high school, he worked as a stringer reporting school sports. “At 25 cents an inch,” he recalls, not too ruefully, “I could make the description of a basketball game go on a long time.”

But Vermont irresistibly beckons, and as he turns the car back onto the highway north, the conversation shifts away from the Boston suburbs and toward the value of small-town life. McKibben lived in New York City for five years after college, writing “Talk of the Town” pieces for The New Yorker. But in 1987, he and Halpern, then newlyweds, bid good-bye to the city for the wildness of the Lake Champlain region. Their first stop, in the New York Adirondacks, “was a very rural, sort-of-forgotten town,” Halpern interjects from the back seat. “Not the sort of place people summer in. Bill got involved with the Methodist church. It was falling on hard times, and he agreed to teach Sunday school. He even got me involved—which is hysterical, because I’m Jewish.” Halpern also worked on building a local library from scratch (an experience that she relocated to Riverton, New Hampshire, for her own new novel, Summer Hours at the Robbers Library). Going all-in, she says, “was our gateway into the community.”

It was the same, adds McKibben, when they moved 50 miles across the lake, to Vermont, in search of a better school for their daughter. “There’s this whole mythology that you can’t be a Vermonter for seven generations, and we found that was not true,” he says. “If you are willing to work on things other people are not wanting to do, and if you’re careful not to boss people around, or tell them how to do things, they accept you.

“Neighbors have been optional in much of America for the past 50 or 60 years, but they’re not optional in rural places,” he continues. “My belief is that they are not going to be optional for anybody before long. They’re not optional in Florida this week. Or in Houston.” Hurricanes Irma and Harvey had just devastated those two areas; Maria was still two days away from demolishing Puerto Rico. “The old American idea that you can get by on your own is beginning to alter.”

As we head out past the Boston exurbs of southern New Hampshire, McKibben’s undercurrent of restless anticipation seems to strengthen, as if he is beaming down some special North Star energy. “It gets comfortable around Concord,” he promises. “Everything thins out.” And then, leaving Concord behind, he adds, “Just about here we are starting to feel we’re escaping the gravitational pull of the megalopolitan region.” A little later, he and Halpern make their ritual pause at the Methodist Hill rest stop in Enfield, New Hampshire, just before the bridge into Vermont, as if they are about to enter the Promised Land.

McKibben says he noodled around for years with his new novel, partly a New England homage to Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, a celebrated 1970s account of environmental renegades taking on bulldozers and dam builders in the American West. The triumph of Donald Trump and an administration that largely refutes climate change science pushed him to publish now, McKibben writes, with the moral that “when confronted by small men doing big and stupid things, we need to resist with all the creativity and wit we can muster.”

But Radio Free Vermont is also plainly a love letter to the state that sustains McKibben as he struggles with what he flatly terms “the end of the world.” The enormity of that “floored me for a while,” he says of his early years working on climate change. “I was depressed for quite a while. And now I have, to some degree, come to terms with that. The angst is familiar by now.” Humor and entertainment still help take off the edge. “And to be out in the woods whenever I am home is, for me, essential.”

So the new book features a band of aging cross-country skiers and a 72-year-old radio announcer with a fondness for reporting high school sports. There’s a woman who runs the School for New Vermonters (teaching retired but self-important doctors and lawyers how to fell a tree, drive through mud, and volunteer with the local fire department). There’s lots of knowledgeable talk about Vermont microbrews (“Did you know we had more breweries per capita than any place on Earth?” a character asks), plus a truck-jacking ambush that involves dumping 4,800 bottles of Coors Light (and recycling the empties). There’s also a socially awkward young technology whiz with an encyclopedic knowledge of pop music: At one point, to inspire followers, he proposes playing any of three versions of “Get Up, Stand Up (for Your Rights)”— by Bob Marley, or Peter Tosh, or Toots and the Maytals, “but really not the Tracy Chapman version, I don’t think.” It’s an unexpected bit of dialogue to have been penned by the leader of the climate movement.

McKibben’s rebels travel under a slogan from Ethan Allen, the original Green Mountain Boy: “The gods of the valley are not the gods of the hills.” And it becomes clear that the gods of the hills are McKibben’s gods, too. “When November came and the days grew short, his mood always began to soar,” he writes, attributing the thought to the radio announcer leading the Vermont secession movement. But what comes hammering through is McKibben’s own passion for winter and for cross-country skiing. “Cold meant snow and ice, and snow and ice meant: sliding. Meant the annual exemption from friction, meant that a solid Vermont farmboy became fast and agile. Graceful almost…. It was the sheer painful pleasure of charging fast uphill on a pair of skis, legs pistoning, lungs sucking in air, skis slamming against a hard track.… It never stopped seeming unlikely and magical to him, the way friction just quit, and gravity turned from adversary to ally.”

Photo Credit : Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

McKibben’s passion for cross-country skiing is hardly a secret. When he was 37 and in need of “a break from failing to save the world,” he wrote a book, Long Distance, about undertaking a brutal training regimen meant to turn him into a world-class athlete in a year. When the year ended, he kept at it, and what’s surprising is the degree to which it still defines his life. He says he tries to confine his climate change appearances now to spring and fall, and to stay home in the colder months, when, friends say, he can get in more than 100 days a year of skiing. “His love of skiing is pretty legendary,” Andrew Gardner, a Middlebury publicist and professional cross-country skier, later notes. “He’ll call and say, ‘Hey, there’s a half an inch of snow on a field’ that’s barely slideable, and he’ll go ski on it, and I won’t. He has a hard time slowing down, and I don’t think he’d take on the work that he’s doing without that.” McKibben, he adds, “doesn’t socialize normally, doesn’t sit down and chill out.” If he’s going to talk, it will be while he’s skiing, or on a hike, “not sitting in a chair and calmly looking,” but always moving, and usually moving hard. “He has a ridiculously hot nervous system, and that fire gets put out by skiing. It takes him down to a place where he can be sort of comfortable.”

The irony of having chosen cross-country skiing as his distraction and his consolation, as McKibben himself volunteers, is that “no recreation on earth is more vulnerable to climate change.” It’s almost as if the haunted Norwegian minister in him has deliberately chosen a diversion that keeps damnation in front of his eyes. “But no glide now,” he has a character in the novel declare, “and not much for the last few years. The globe had warmed faster and harder than anyone had ever predicted.… He knew he should have been worrying about the people in Bangladesh busy building dikes to keep the sea at bay—but these warm muddy winters were what really bothered him about the change. No glide, just the suck of mud on his boots.”

The drive north takes McKibben and Halpern through Bethel and Rochester, Vermont, river towns submerged by the epic 2011 floods caused by Hurricane Irene. They point out the landmarks of destruction with a certain traumatized awe. A bridge collapse there. That playing field up to your shins with silt.

“Most politicians don’t yet understand that we have to move very, very quickly,” he is saying. The usual political process is to “meet somewhere in the middle and come back in 10 years to see how it’s working. We don’t normally want dramatic change that causes all kinds of economic loss. But my mantra on this has become ‘winning slowly on climate change is just another way of losing.’”

He is on his talking points now, saying things he has written and said before, and will need to say many times again. As an aside, he says, “There is something disconcerting for a writer, repeating the same message over and over, which is not what you set out to do.” A friend, Middlebury newspaper editor Angelo Lynn, later says, “Bill’s not Bernie Sanders. He doesn’t love the limelight. He would rather be writing his books and holed up in Ripton and have that change the world. But it didn’t work out that way; that’s not the life he got called to.” The life McKibben got called to, moreover, is unlikely to let go of him anytime soon. “If you’ve been as all-in as Bill has been for so long,” says Halpern, “there’s no way you can say, ‘I’m done with this.’ The thing about Bill is that he has really good ideas.” She runs through a list of inventive political actions McKibben has instigated to keep the climate movement growing. “If he stopped thinking up these things, that would be a great loss,” she concludes. “And I don’t think he can.”

“The problem with climate change,” McKibben continues, “is that it’s not between two groups of people, but between people and physics, which is uninterested in compromise, unmoved by spin, uncaring that your economy is at a weak point. It means you are going to have to meet the terms of physics, and that means we have to move fast, possibly faster than we know how.” The great hope, he says, is that public alarm about climate change will lead to outspoken and urgent demand for action. And the great fear is that this is a timed test, with President Trump and his gang of climate skeptics running minutes off the clock that the planet can never recover.

But just then the roads become steeper and the forested hills turn mountainous, and McKibben says, with a kind of possessive delight, “This is our country now. We’re going to climb up onto the ridge of the Green Mountains.” A little later, driving up the dirt road to their house, he sighs and says, “There will be a time in November when there will be snow on the ground from here on up the hill.” The leaves have just begun to turn. “Oh, and they’re really starting to pop!” he says. It’s as if he has been away for weeks, not overnight.

They arrive at the board-and-batten house they built years ago—he calls it “a big screen porch with a few rooms attached,” plus a battery of solar cells on the roof and in the yard. Bill McKibben is home and, at least for the moment, no longer in motion.