Vermont Neighbors and Online Networks | How New England Can Save the World

How New England Can Save the World: Part II in a series Part I: 2011 Biathalon World Cup: Aroostook County Part III: Hardwick and the New Frontier of Food Part IIII: A Bang for Your Buck in the Berkshires When Michael Wood-Lewis and his wife, Valerie, moved from Washington, D.C., to the south end of […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

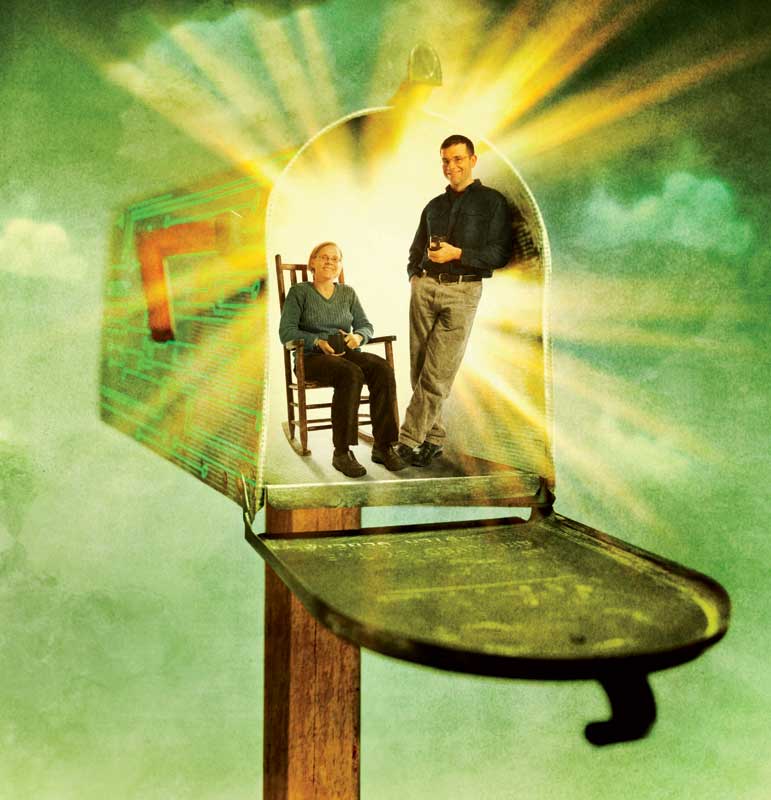

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanHow New England Can Save the World: Part II in a series

Part I: 2011 Biathalon World Cup: Aroostook County

Part III: Hardwick and the New Frontier of Food

Part IIII: A Bang for Your Buck in the Berkshires

When Michael Wood-Lewis and his wife, Valerie, moved from Washington, D.C., to the south end of Burlington, Vermont, in 1998, “we’d landed in what we thought was our dream neighborhood. It was walkable, near the lake, full of trees. But we were having trouble getting to know the neighbors.

One night, we were sitting around the dinner table talking about it. It hit us that in the Midwest and the South, where we were from, people brought cookies to their neighbors. We’d been here a year–where were our cookies?”

Hence plan one. They baked up a batch of Toll House specials and delivered them to the neighbors. “We used china plates, because I figured that way they’d have to return them and we’d get another conversation,” Wood-Lewis recalls. “We never did get them back. I was kind of dumbfounded. But I don’t think it was because people were rude. I think it’s because people are living in a different culture than they were 50 years ago.”

A culture busier and more distracted than ever–busy enough that even in Vermont, the state with the biggest rural population percentage in the Union, famous for its town meetings and its civic engagement, something had changed. So, in 2000, Wood-Lewis cooked up plan two, which may just turn out to be one of the most innovative (and deceptively obvious) uses of the Internet so far. In his hands, the Net has become a way to meet not people half a world away, but half a block.

“I invested $15 at the copy shop, printed up 400 fliers, and put one on every door in our neighborhood,” Wood-Lewis explains. “It pretty much just said, ‘Share messages about lost cats and block parties.'” Thus was born the Five Sisters Neighborhood Forum, which he ran as a volunteer effort for six years. “It took about five minutes a day, and I was already on the computer anyway,” he notes. Every evening he’d compile the five or six messages that had arrived at his inbox during the day and send them out in a single e-mail bulletin. That was it.

Someone would write in: “Neighbors, FYI: Late last night I observed a large possum ambling across my front yard. Not as bad as a skunk, but I understand that possums can damage gardens and dig up lawns.” Twenty-four hours later, another neighbor would respond: “They have very soft feet that aren’t good for digging and aren’t likely to cause lawn damage–and they’re very clean animals and spend much of their rest time grooming themselves.”

Meanwhile, someone else had pruned his apples trees and wanted to share the news that he had kindling piled up on the back porch free for the taking. Down the street someone’s car had been broken into: only thing taken was a gym bag filled with “my shoes, some sweaty clothes, and a couple of issues of The New Yorker. If anyone finds it dumped in their shrubbery, let me know.”

Forget the World Wide Web–this one stretched barely four blocks. And no video, no rating systems, no celebrities, no hyperlinks. Just the daily rhythm of neighborhood life. “It grew steadily, from 10 or 20 percent of the neighborhood to the point where by 2006 we had 90 percent of the neighborhood signed up,” says Wood-Lewis.

That’s when Cottage Living magazine included the area in its list of the 10 best neighborhoods in the country: “And the reporter called me and he said that everywhere else in the country people would have dozens of different reasons why their place worked. But here, almost everyone put the e-mail thing on the list. That’s what gave me the confidence.”

The confidence to quit his job and start offering the service across all of Chittenden County, Vermont’s most populous. Within two years, Front Porch Forum (FrontPorchForum.com) was reaching 15,000 households and participating in more than 100 neighborhood nets; last fall it expanded into Grand Isle County.

Some nets are in inner-city neighborhoods, where the main topics are how to fight graffiti and drive away drug dealers; some are in rural towns where the messages include: “We have four Indian Runner drakes whom we expected to be females and lay beautiful round eggs. Instead we have these guys who really need some girls!”

This sounds like the stuff you’d see in the letters-to-the-editor column, or on the bulletin board at the supermarket–and it is. But now it comes in an easy-to-use daily update that somehow breaks down barriers. “My sense was that this skill of neighborliness had eroded,” says Wood-Lewis, citing data such as Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam’s famous book Bowling Alone. “If you could increase social capital in a neighborhood–that is, your network of whom you know and how well you know them–then your involvement increases. If you’re among strangers, you’re not going to volunteer for the Girl Scouts.”

Sound theoretical? Not long after he’d launched his first forum, one of Wood-Lewis’s neighbors was moving from an apartment to a house across the street. “They figured they could do it by themselves, but at the last minute decided they had a couple of big items they’d need some help with,” he says. “So they put a note on the forum saying, ‘Come Sunday at 2’–and 36 people showed up. People didn’t just move the chest of drawers and the bed–they organized into teams and boxed up the entire contents of the house, moved it across the street, and unpacked it, all in 90 minutes. I mean, someone pulled the picture hooks out of the wall in the old place and spackled over the holes. All the cardboard boxes were broken down and ready for recycling.”

The lucky couple had known at best a dozen of those people before, says Wood Lewis: “But now they know them all. When they push a stroller around the block after that, it’s like living in a community. And when the call comes to spend a Saturday helping put in a new park or something, you know they’re going to be there.”

The genius of the system flows from the ways it’s unlike the rest of the Web. Instead of going global, each forum is limited to a neighborhood of about 400 homes. Instead of the anonymity that lets Internet users happily flame one another, all the folks participating in these forums clearly identify themselves. “I designed it to be as simple as possible–to use plain-text e-mail, so that everyone can take part,” Wood-Lewis explains. “I just heard from an 80-year-old grandmother who’d signed up. She said, ‘We’ve been here 50 years, but all the people we know have moved away, and we want to stay connected.’ That’s the kind of person we want to serve.”

The biggest difference between Front Porch Forum and the rest of the Web, though, is that its ultimate goal is to get you out from in front of the screen and into the world around you. “The real feedback loop is on the main street of town,” says Erik Filkorn, in his eighth year on the select board in Richmond, Vermont. “You’ll be coming out of the store and someone will say, ‘Hey Erik, I saw the thing you wrote. Here’s what I think.’ You’re not just creating an avatar and hanging out in a singles bar in Second Life–not that I would do that. But this is very much grounded in the flesh-and-blood community.”

So grounded that it may already be the most important source of information for many Vermonters, who have watched their main newspapers lay off reporters and shrink coverage. “One afternoon last year the state closed our main bridge as unsafe,” recalls Filkorn. “As a member of the town government, I sent an extra to Michael Wood-Lewis, and he got the word right out. I think more people got the news that they’d have to change their morning commutes from him than from the traditional media.”

But it works in emergencies only because people use it every day–the steady stream of lost cats, and people looking for summer jobs for their teenagers, creates the community that people then rely on at more crucial moments. “It’s fun, mostly,” says Filkorn. “I remember a post from a guy who said he was going to a wedding and needed a tuxedo, size 40. Well, I had one. Derek took it, and he returned it to my office, dry-cleaned.”

From tuxedoes to potholes, from potholes to politics … Susan Comerford, a longtime community organizer and now associate dean for academic affairs and research at the University of Vermont’s College of Education and Social Services, calls it “the best community organizing tool that’s come along in the last 30 or 40 years.” To understand its importance, says Comerford (who started posting on the forum the day she needed a recommendation for a carpenter), you have to think about what’s happened in the American economy in recent decades.

“It’s not that people care less about community,” she notes. “It’s that the economy has shifted how much people have to work to keep up their standard of living. You don’t have one of the two partners home during the day making all those social connections, providing some sense of safety to the neighborhood. People have less disposable time than they used to.”

In a world like that, a system that lets you sit down for 10 minutes at the end of the day and learn what’s happened to your neighbors should, in Comerford’s view, earn Wood-Lewis one of those MacArthur “genius” grants. Wood-Lewis would probably welcome the recognition of his idea, and the check would come in handy, too. The forums aren’t breaking even yet: Subscriptions are free, and revenue comes from a few unobtrusive ads at the bottom of each e-mail. Also, city government pays a fee for the right to post public notices on the system. “With a few hundred thousand dollars of development money, we could put this software in a box and set it up anywhere,” Wood-Lewis predicts.

Which would mean one more good New England idea spreading out across the country: people everywhere able to, say, ask their neighbors if they had some topsoil, or maybe a cake pan. (“I’ve decided to move beyond my comfort zone and make a torte for a Passover seder to which I’ve been invited. For this I’d need a 9-inch springform pan. Yes, I could buy one. But I’d rather borrow one for this first and probably only attempt.”)

It would mean that more people could borrow a compost tumbler, or find out about a new study at the university on the effect of caffeine on snoring, or see whether anyone wanted to go halves on a grass-fed steer from a local farmer. It would mean that everyone could see the wish list for donations for newly arrived African immigrants who’ll be planting gardens come spring (wheelbarrows, rakes, hoes, scales), or find out about the neighborhood plant swap (“We just want all our perennials to go to good homes”) or which porch to visit if they want to rummage through big bags of “dress-up and costume clothes.” “Seeking moped repairs,” “Ethiopian food available,” fourth graders selling honey-glazed donuts to fund their trip to the science museum (made with local wheat!).

It would mean we could all be the good neighbors we’d like to be. “There was a mother near us, with a teenage daughter who was having a birthday,” Wood-Lewis recalls. “The girl wanted to go canoeing with her friends for her birthday, but when her mother checked out the price of renting canoes, it was too high. Her daughter said, ‘I see lots of canoes in backyards around here,’ but her mother said, ‘You can’t just ask people you don’t know for their boats.’

“Still, she put a one-line notice on the forum, saying they needed six canoes. Before the day was out, people were coming by. I mean, there were canoes just piling up in their front yard. She wrote me a note afterwards: ‘What a great feeling. What a great reminder of how to be a community. Why didn’t I get to know these people 10 years ago?'”

READ PART I: The Maine Way

Love it! McKibben hits the nail on the head… this is one of those New England tools that should be in every community across the country. We just weathered a stormy Town Meeting Day this week, and neighbors talked with neighbors for weeks in advance about the issues in ADVANCE of Town Meeting, leading to better results… and Front Porch Forum played a large roll. I had lots of talks with local folks about the issues at the market, school, workplace, etc… and they usually started with “did you read what so and so said about X on Front Porch Forum?” And then we were off and running. Before FPF, I rarely spoke to these people. Good call Yankee… you’re improving with each issue lately.

This story is so simple, moving, and inspiring! What a great way to solve the bizarre problem of not knowing who your neighbors are. I love it!!

This was great!!! I’ve been living on 25 ann rd in long valley, nj since May 1992 and rarely see my neighbors even in spring or summer, never mind in the dead of winter! this article says 2nd in a series, I think I missed the first one, anyone know about it? thanks so much!!!

Thanks for your interest. Part I is “The Maine Way.” There’s a link at the beginning and end of this article, or you can copy this URL: http://www.yankeemagazine.com/issues/2010-01/features/Maine-jobs-sports-winter

Wonderful article. I just moved to a Vermont community with a FPF from a neighborhood in the western US that was purposefully platted to discourage interaction with one’s neighbors. That was a cold existence, let me tell you. After just one week I know more about my new area than I did after six years in the other neighborhood, and can’t wait to get started in the life of the greater community. It is pretty wonderful.

Great article. Mr. Wood-Lewis should indeed receive as many awards as available for his effort in this very difficult mission to connect neighbors. Neighborhoods are indeed on a decline across the country. We have been feeling it and recent research confirms it. With the same passion and sense of urgency to connect neighbors, I started something similar in the East but that makes it really easy, fast and free to bring any neighborhood online. http://www.ToolzDO.com is a social platform dedicated to connecting neighbors and building community. You get the same benefits and more at no cost, no setup time, with less resources and overhead to maintain. We have members in over 200 cities in the US and span across 3 continents. Check it out. It’s all free which enables faster adaptation. We actually pay community builders and organizers who bring their community online and charge nothing for customization. Thus far it has been a labor of love as well. I think distributing the love and resources on a common and tightly integrated platform would have the greatest impact in this movement to reconnect neighbors. By harnessing technology the limits of community size or administrative borders can be removed and neighbors can truly be connected to the neighbors near them or in their own backyard.

Thanks to Bill McKibben and Yankee Magazine for shining a spotlight on all the wonderful community building underway by Vermonters through Front Porch Forum. Thanks too to the commenters above and the folks Bill quoted in the article. We look forward to expanding to other communities. If interested, go to http://frontporchforum.com/join and let us know!

P.S. And we greatly appreciate the two dozen VT state legislators who are co-sponsoring a resolution honoring Front Porch Forum this month… http://bit.ly/bRa9HM

Excellent story. What the Front Porch Forum has done extremely well is create a network of small scale semi-private spaces among neighbors. Over here in Minnesota (mostly, but also England some) we’ve been working our way down from city-wide online civic forums to the larger, but still public neighborhood level (a few thousand households in my case where I have about 450 of 4,000 households on a forum … we just had a potluck last night). According to the Pew Internet and American Life project, some 4% of American adults say they are on a neighborhood e-mail list. With FPF and sites like NeighborsforNeighbors.org in Boston and my E-Democracy.org we are the most visible because we serve multiple communities. So whether you work to bring FPF to your community or doing your own thing, it is time to bring this idea to the other 96% of people!! I am trying to connect anyone interested in building local communities online here: http://e-democracy.org/locals