Written in Stone | The Artisans of Hope Cemetery

In Barre, Vermont, generations of stonecutters have made a cemetery into a garden of stories.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Cecchinelli is the last of the renowned Barre artisans, who predominantly used traditional hand tools rather than pneumatic ones. He looks the part, too, with his pointy beard, and floppy beret, and muscled arms. Using mallet and chisel he turns the hard, heavy granite into mortuary pieces depicting a soaring plane or a billowing sail or Mary’s sorrow.

Just inside the studio, on a tiny table, he’s created the face of an older woman; her head rests on a pillow, and she looks as if her health is fading. “That’s my wife,” he says of the work in progress. Cecchinelli was with her when she died in December 2015. He calls this piece “Last Breath.”

While Cecchinelli’s art has captured a first breath as well—another of his carvings features a newborn being tenderly relayed from one pair of hands into the waiting hands of its mother—what he is best known for is commemorating all the life experienced between these moments. Consequently, his art can be found throughout the globe. But an exquisite showcase of Cecchinelli’s work, more than a dozen monuments in all, is just down the road in Hope Cemetery.

Well, you want to go? he asks. I do.

———

Barre, Vermont, is situated amid one of the largest deposits of sculpture-quality granite in the nation, estimated to be four miles long, one to two miles wide, and 10 miles deep. In the 1700s, settlers began prying this prehistoric rock out of the ground to use for millstones, fence posts, steps, and sills. After Barre’s first commercial quarry opened in the mid-1820s, the extracted granite was used for curbs and to undergird buildings and to line streets—for example, the city of Troy, New York, ordered 10 million hand-cut granite paving stones. In other words, Barre’s mother lode was used as something to step on.

However, after an industry delegation from Barre marketed their durable material at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, orders poured in for more-refined granite products. Architectural and mortuary goods manufactured from “Barre Gray” were soon being used in the mausoleums of F.W. Woolworth and Walter Chrysler, as well as for headstones of the less well-known. Monuments traveled via railroad to New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, Virginia, and Tennessee. In Pennsylvania, Barre granite was used in the construction of the state capitol. In Manhattan, it composes the 16 columns in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

In 1903, when architects began planning Washington, D.C.’s immense Union Station, a Barre-area company was awarded the largest single stonecutting contract for a building, at $1.3 million; its stone carvers ultimately produced six colossal statues for the station’s facade. By the turn of the 20th century Barre’s granite industry was making things to stare at. Today, Barre products constitute an estimated one out of every three monuments nationwide.

“This story is enormous,” Vermont Granite Museum director Scott McLaughlin tells visitors who wonder how much significance a stone can hold. The museum was founded in Barre in 1996 to educate the public and celebrate this city’s history. Appropriately, the museum is housed in the former cutting shed of Jones Brothers, once the largest raw-block-to-finished-product operation in Barre, and within its 27,000 square feet the exhibits explore everything from the geology of granite to the social lives of the stoneworkers to the art being sculpted by the next generation of carvers.

“Now that you’ve seen the museum,” he often tells visitors, “you have to see Hope Cemetery.”

They look at him with wilting smiles.

“The cemetery?”

———

Along Barre’s streets you’ll find at least a dozen granite monuments. Basking near a 14-pump gas station is one made to resemble a Victorian couch; it commemorates the “forever residence” of the Zanleoni family, where Angelina raised her children and sold homemade ravioli. On South Main Street, there’s a bike rack bookended by life-size granite reproductions of Big Wheel tricycles. Traditional masterpieces, such as Sam Novelli and Elia Corti’s 1899 sculpture of poet Robert Burns upon a pedestal intricately carved with scenes from his poems, abide by unconventional ones, such as sculptor Chris Miller’s granite zipper.

Over the past century, Barre has been home to more granite carvers than anywhere else in America. Even so, the city is a long way from fulfilling Miller’s proposal to have so much public art that pedestrians could encounter it every 10 feet.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Yet that’s exactly what happens at Hope Cemetery. Both a resting place and a local showroom, the cemetery offers a permanent exhibit of granite monuments in unusual shapes, such as a race car, a soccer ball, and a couple in pajamas holding hands in bed.

Cecchinelli and I turn onto the hilltop cemetery’s main access road and drive through its entranceway, which is flanked by a pair of pious Virgin Marys. Then we pull off to the side of the road and begin wandering on foot among some 10,000 monuments set upon 85 acres, all made from the area’s famous rock.

Hope Cemetery was established in 1895 to create an additional resting place for the city’s surging populace. Instead of implementing a gridded layout, the cemetery’s draftsman, Edward P. Adams, arranged the grave sites in groups and constellations, partitioned by hedges and mature trees, so that visiting the property now feels like browsing the adjoining rooms of a gallery.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Cecchinelli shows me one of his first jobs, a monument featuring some handsome columns. He scowls at his novice work, because, he says, they should taper at the top. But they don’t, and the flaw still haunts him even though the work looks solid and strong. We amble over to view his more recent works: Here is the gravestone he sculpted into a biplane tipping out of a pillowy cloud. And here is one he made into giant prayer-tented hands clasping a bouquet of lilies. And here is one of a boat under sail aimed toward a far-off horizon. And then there’s a primly dressed woman, waving good-bye to her husband, who’s hunkered on his motorcycle—it’s so broad and detailed, it has the feel of a mural. And here is another of Cecchinelli’s memorials, this one portraying the departed wearing an Italian jacket and holding a cigarette in which his lovely wife’s visage miraculously coalesces in the smoke.

Next to diamond, granite is the hardest natural material on the planet. To work the rock so that it expresses a biplane’s propeller or a lily’s pistils or wafting smoke (that blooms into a woman!) is a feat of effort, for even after drilling and excavation, the manufacturing process is boisterous, organized violence. “I come home sometimes and my arms are just dragging from having to push against this incredibly hard medium,” one stone carver admitted to the Burlington Free Press in 1985. Furthermore, these beautiful deceptions—for example, stone made to look like skin—are the product of supreme talent, and Cecchinelli, like many of the Barre stone carvers who arrived from Italy, was trained via a chain of masters passing on their techniques to apprentices, a chain that links back centuries to artists like Michelangelo.

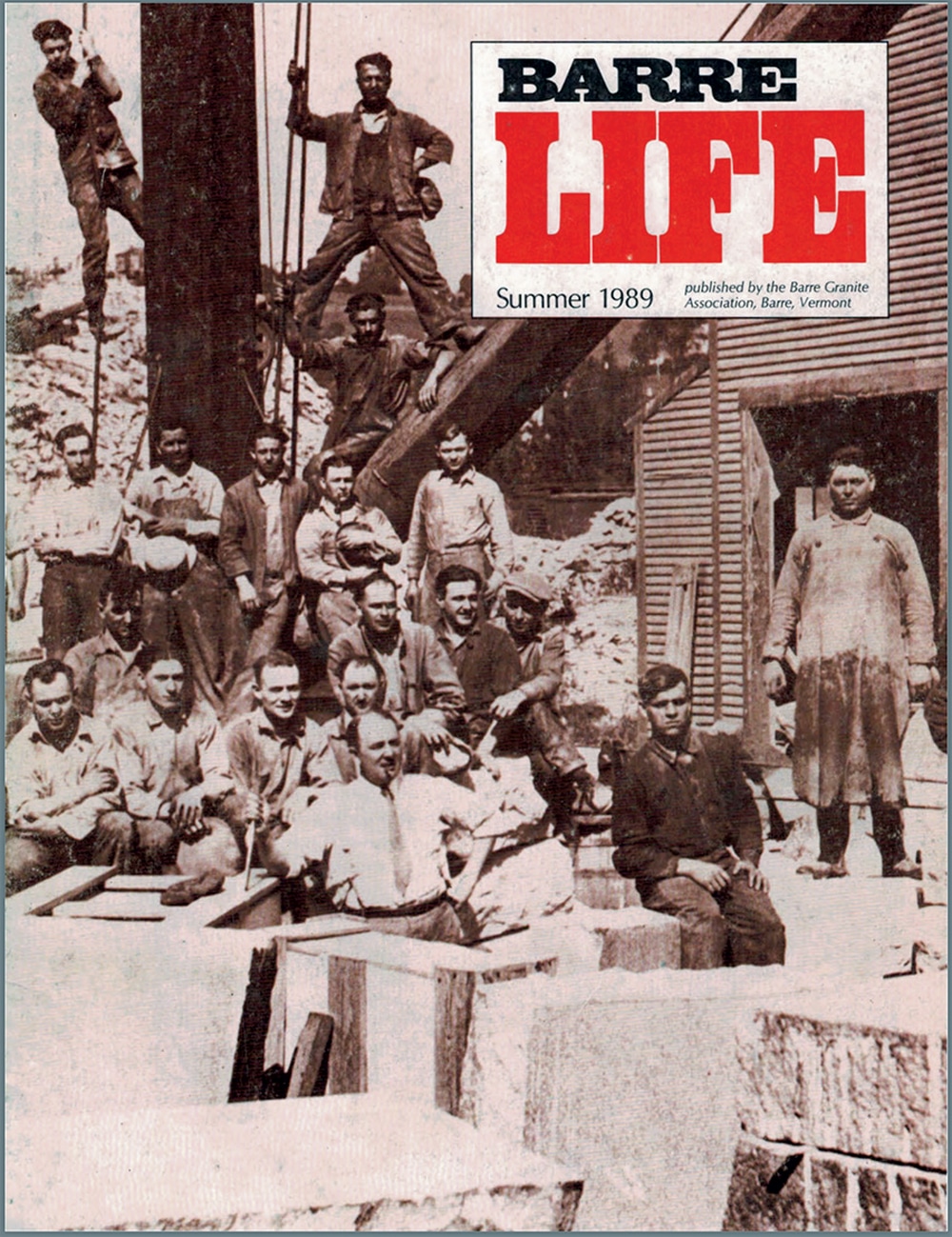

To meet the labor needs of the thriving granite industry, skilled stoneworkers moved to Barre in droves. Between 1880 and 1940, the city’s population swelled from 2,206 to 11,855. They arrived from Canada, Scotland, Scandinavia, Spain, Poland, and France, but mainly they came from Italy. Cecchinelli’s family joined the influx relatively late, arriving from Carrara, Italy, in the 1950s, when his father began to work for a marble company in Proctor, Vermont.

Growing up, Cecchinelli learned to carve marble, but later moved to Barre to work in granite. Explaining the difference between the two mediums, he is emphatic: “Marble, you cut. It bruises—just like an apple. But granite?” he growls. “You have to pulverize. You have to beat the life out of it!”

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Cecchinelli shows me a modest stone tucked back in the shade of a juniper, a rough-edged monument featuring a maiden in a long gown holding a drooping flower over the names of the deceased. Looking at the peaceful scene, it’s easy to disregard all that culminates here. Beneath the stone lies a man who in 1901 left behind everyone he’d known in Italy and crossed the ocean. In Barre, he went into business and started a family, but as the newspapers reported, the man of “kindly impulses,” who helped translate for workers with poor English, ended his life at 54, ingesting arsenic when a health issue and “adverse business conditions” began to overwhelm him. The stone also commemorates his daughter, who survived him but was still a young wife and mother when she died in 1930 of a sudden illness.

This lovely double memorial was executed by one of the most accomplished sculptors in Barre, Angelo Pietro Ambrosini, another Italian native who crossed the ocean in 1901. Because the departed and the stone carver knew each other, it’s possible that Ambrosini furnished his services for free, as was common among friends in the industry. However, within two years of completing this monument, Ambrosini also became a permanent resident of Hope, at 52.

And herein lies the story’s terrible irony: That what makes Barre’s granite so ideal, also makes it lethal. When it was formed (“Before humans even existed!” Cecchinelli reminds me. Yes, nearly 400 million years ago, long before dinosaurs, eons before humans walked the earth, which means before mortality itself!), some magma cooled slowly and evenly, allowing fine silica grains to be spaced uniformly within the stone. It’s this feature that ensures the granite will scarcely erode, even as it’s exposed to weather over the next million years. Yet as the men labored in poorly ventilated sheds—chiseling, hammering, polishing—shattering crystals in the rock, the air around them filled with silica dust. And this by-product cut their lungs.

———

To know the story of Angelo Ambrosini is to know the story of many. He boasted to his family that he would not get the stonecutters’ disease known as silicosis, even though by the 1920s the life expectancy rate for men in the industry was less than 50 years. In 1922 the Washington County Tuberculosis Hospital opened in Barre to treat laborers with silicosis-related TB. Unfortunately, because of the high mortality rate from the disease, many viewed the hospital not as a place to heal, but as a place to die.

From 1903 to 1907, Ambrosini was one of four stone-cutters who worked on the Union Station contract. Newspapers praised his skills, which they claimed had persuaded the station’s designers to select granite over marble. By sculpting a figurine with “flowing hair … robed in rippling garments and … flowers cradled in her arms,” as the 1974 history book Green Mountain Heritage recounts, Ambrosini had proved that “granite could stand the stress required to make the fine detail needed in the huge tableaux.”

Thus Ambrosini and the others began to sculpt the largest works ever cut from single blocks to produce the six “heroic statues,” each made from a piece of granite weighing as much as 85 tons. Based on models created by Louis Saint-Gaudens, the less famous brother of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, they represented “The Progress of Railroading,” as each figure stood for an aspect of train travel: science, liberty, electricity, justice, agriculture, and mechanics. When I meet Ambrosini’s son and namesake, Angelo, he says his father spent a whole year just working on Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and the harvest.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Unfortunately, working environments for carvers in America differed from the open-air structures found in Italy. The stone sheds in and around Barre were shut tight in winter to keep out the cold. As a result, they clouded up with dust that stuck to anything moist. Sometimes there was so much dust, a carver couldn’t see the man working next to him. I picture Ambrosini using the newly developed pneumatic tools as he pulverizes stone, making the folds in the goddess’ dress, and developing her thick tresses, and delineating the seeds in her sheaves of wheat. I imagine the month he devotes just to carving her arm, leading into her hand, gripping the reaper. And as the block of granite transforms into majestic Ceres, Ambrosini breathes.

The final statues weighed somewhere between 25 and 40 tons and stood 18 feet high when, at last, they were transported via railroad to Washington, D.C., for installation in 1912 and 1913. Special derricks hoisted them onto their platforms, 50 feet above street level, where they continue to endure, more than a century later, in the station’s facade.

After the statues’ completion, Ambrosini returned to his hometown of Varese, Italy, to propose to his local sweetheart, Rosa. Although she said yes, she qualified her answer, stating she would not leave Italy. However, her teenaged sister, Maria, overheard the proposal and volunteered to marry him instead. Within two weeks these newlyweds were on a steamer to America. Eventually they rented a hilltop house in Barre and raised four children, naming their two daughters Aurora (meaning “the dawn”) and Louisa Liberty, and calling their two sons Avveniri (“the arrival”) and Angelo Lincoln—all in honor of their adopted nation.

Ambrosini’s daughter Aurora reminisced in her unpublished Memories of Ma and Pa that granite manufacturers often climbed the hill to their family home carrying specifications for various stone projects, which her father would consider carefully. If he got the contract, he would make a preliminary model, called a maquette, working in the basement of the family home or a spare room. Sculpting the small figurine out of clay, he sometimes used Maria as a model or, Aurora writes, “my sister Louisa, too.” Then Ambrosini would leave his family for the granite sheds, where he’d cut the work into rock.

———

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

In Hope Cemetery, all the monuments allude to the joys of living, with the exception of one. Luigi “Louis” Brusa (1886–1937) was a carver who designed his own stone to depict the egregious way he died. His grave features a woman attending a collapsing middle-aged man. The man’s eyes are already closed, and his arms hang slack by his sides. The work includes so many details: the dimple in the woman’s elbow, the skim of her dress, his rolled-up sleeves, and, poignantly, his hollow cheek, resting in the crook of her arm.

In an oral history project published in 2003 as Men Against Granite, a widow describes the onset of silicosis as “a terrible sound, that coughing, [that] kept getting worse.” In the fall of 1931, only a year after Ambrosini had finished that monument honoring his deceased friend and his daughter, he was diagnosed with silicosis. Before, whenever he had medical issues, his wife, Maria, always knew what to do. On the occasions when he came home from the granite sheds with a sliver of steel from a broken-off chisel in his eye, she’d turn up his eyelid with a wooden match and deftly pick out the sliver with a broom straw. But now, neither she nor the doctors had any remedy. “In those days there was only rest, either at home or up in the hated Washington County Sanatorium,” Aurora writes of her father’s illness. Silicosis quickly mutates into tuberculosis, which is highly contagious, and Aurora remembers her mother boiling the family’s dishes. And after Ambrosini moved into the sanatorium, Maria would bring him homemade soup, carrying it through the cold streets.

There’s a photograph of the sanatorium in the Vermont Granite Museum. It’s a charmless rectangular brick building with three floors. There are long rows of windows and a balcony. In the 2008 documentary If Stone Could Speak, Aurora said nobody in her family would dare hug or kiss their father for fear of catching the disease. Ambrosini’s namesake, Angelo, who was 6 years old at the time, remembers not being allowed to enter the sanatorium. Consequently, his final memory of his father was when he stood at a distance and waved a white handkerchief. And his father, who stood on the balcony, waved back.

Succumbing in the same manner as the stone man in Brusa’s monument, Angelo Pietro Ambrosini took his last breath in April 1932. His youngest son, now 95, still chokes up trying to speak of it.

Before Ambrosini died, he made Maria promise that she would never allow their sons to work in the granite industry. When I visit Angelo Lincoln Ambrosini (or “A. Lincoln,” as he says with a grin), the first thing he shows me are chipmunks. Angelo, who seems much more youthful than his years, sits behind his house with a few sunflower seeds on his knee. Presently one scurries out of the woods, across the lawn—a russet blur—and then pauses at Angelo’s feet, its tail hanging like a question mark. Then it rushes up his pant leg, grabs a seed, and dashes off. As it scampers back to the trees, it skirts a slab of carved granite leaning against Angelo’s shed. The slab features an eagle, its wing feathers spread open like a cape: Ta-da!

Angelo carved it when he was part of a monument industry delegation that traveled to Washington, D.C., in the mid-1980s to set up a display on the Mall. The sculpture took shape as Angelo gave stone-carving demonstrations with both traditional and modern tools just a mile away (as the eagle flies) from his father’s Union Station goddess. Angelo later told an oral historian at the Vermont Folklife Center, “When I decided to go into [stonework], they had come up with the suction hoses, which made it safe. So I kinda overlooked my father’s wishes and went into the granite business.”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the Aldrich Public Library, Barre, Vermont

In 1936, four years after Ambrosini’s death, the state of Vermont allocated $300,000 for the installation of dust-collection systems, which were installed in 80 of Barre’s manufacturing plants. By 1938 there were no new cases of silicosis, and today, owing to the required use of respiratory devices and ubiquitous suction hoses, there are no deaths in the industry from the disease.

But a generation of men died before being able to pass on their carving techniques to the ones who came after them. Angelo is still pained by what he wasn’t able to learn from his father. His 52-year occupation with the granite industry began in the early 1950s when he enrolled in the Barre Evening Drawing School, which was founded by an Ambrosini family friend, Carlo Abate.

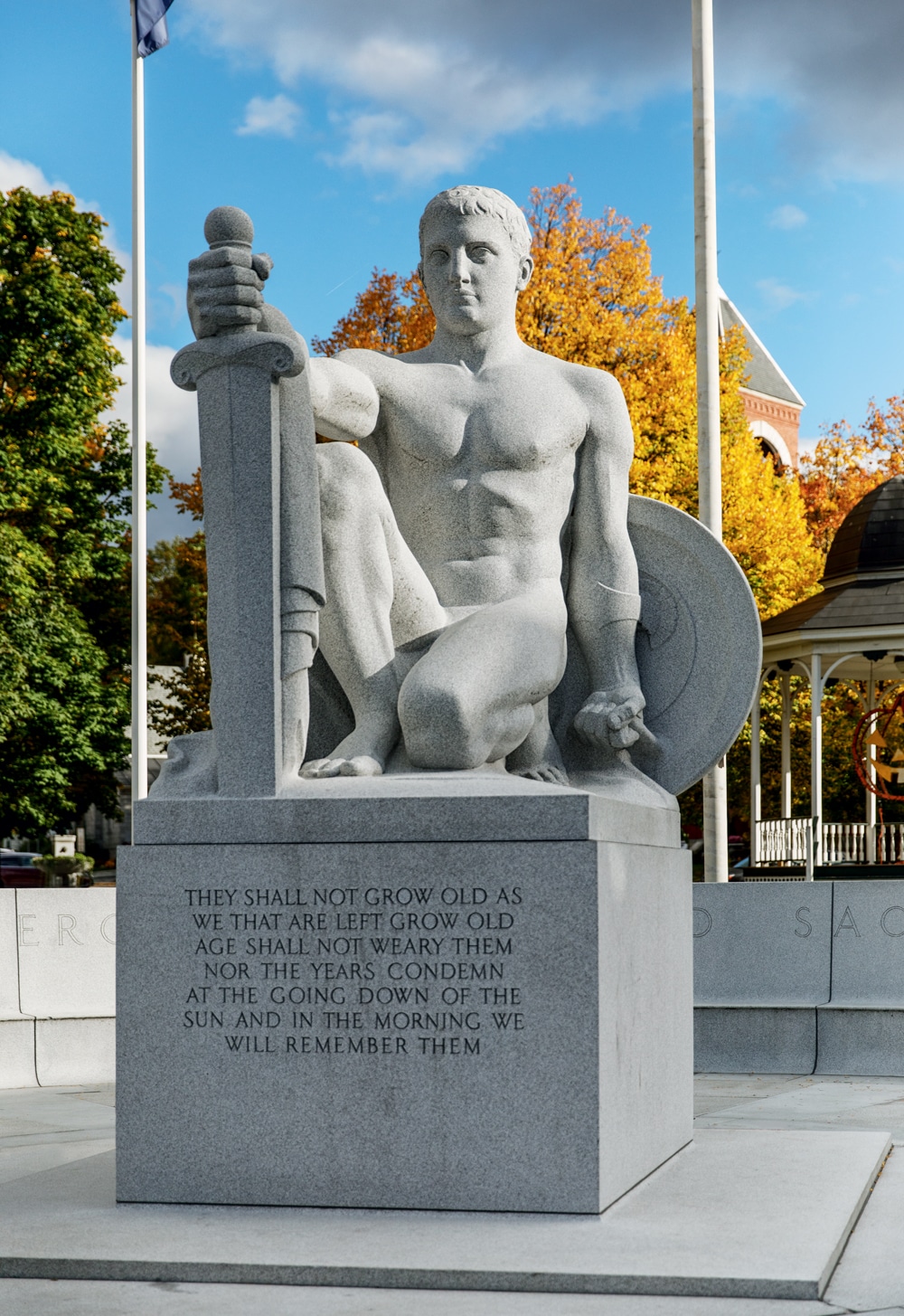

Abate, a lauded carver in his own right who walked around with plaster dust in his beard, emigrated from Milan in 1899. In addition to making a famous bust of Thomas Edison—whom he revered for creating the light bulb, which enabled sculptors to work with longer and better light—Abate also carved the pair of Marys that stand at the gates of Hope Cemetery, using Angelo’s sister Louisa Liberty as a model. And, because everything in this story of Barre’s stonecutters is interrelated, the statue honoring the Italian-American Stonecutter that looms at the intersection of Routes 302 and 14 is dedicated to Abate and is based on a model created by none other than Giuliano Cecchinelli.

This tribute shows a man gripping his chisel and gazing south, in the direction of Mrs. Zanleoni’s granite couch. His bushy mustache and dignified chin give him more than a passing resemblance to Angelo, whose nickname was Barbetta (meaning “whiskers”)—so much so that Angelo’s granddaughter, Louise, actually hopes for a red traffic light there, so she can sit in her car and pretend to visit with the man she never met.

In Ambrosini’s era, women’s involvement in the granite industry was pretty much limited to depiction only—e.g., the Virgin Marys and Ceres—but slowly their presence as creators has been growing. Angelo’s daughter, Mary, is a drafter for a granite company. She designed one of the monuments in Hope Cemetery, a simple stone with an etched name and an illustration of a pine cone, for one of her dad’s hunting buddies. During my visit with Angelo, I notice that he has blueprints for Mary’s latest designs scrolled on his side table, next to the television remote.

Also, within the past two decades the streets and cemeteries of Barre have begun to host the work of one of the first local female carvers, Heather Ritchie. Ritchie, 45, has a slight build and fine features, and looks as if she could have been a model for the sculptors of an earlier generation. She grew up near Barre and is the great-great-granddaughter of a Scottish immigrant who owned a quarry. In 1999, she began an apprenticeship with George Kurjanowicz, a Polish-born sculptor, currently the in-house carver at Adams Granite Company. Under his tutelage she learned to shape the dense material (granite weighs 190 pounds per cubic foot) into angels’ cheeks (for mortuary pieces) and Big Wheels tricycles (for a downtown art commission.)

So far, the only piece she’s carved for Hope Cemetery is buried. When her uncle died in 2015, she honored their shared heritage by hand-carving a thistle onto his granite urn. One of Ritchie’s professional goals is to carve a monument that sits above Hope’s soil.

———

In the Vermont Granite Museum office, there’s a poster published by the 120-year-old Barre Granite Association that reads, “This is a cemetery. Lives are commemorated—deaths are recorded—families are reunited—memories are made tangible—and love is undisguised.”

Love is undisguised—yes, Hope Cemetery is full of it—in the way that the smoker dreams of his wife, and the woman holds her wilting husband, and in the sentiment that parents etched on the stone of their deceased young son: We would give up forever to touch you. The poster continues, “The cemetery is a homeland … a perpetual record of yesterday,” and concludes with, “A cemetery exists because every life is worth loving and remembering—always.”

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Many of the residents of Hope died with dust in their lungs, or from the Spanish flu; some by accidents, others by their own hand. But the cemetery zealously commemorates what they loved, how they thrived. This nearly immortal granite has been shaped to convey how these people were snowboarders, violinists, pilots, baseball players, soccer players, race car drivers, anglers, woodsmen, smokers, lovers. And, case in point, they were neighbors: Cecchinelli shows me a stone with an authentic reproduction of a drilling rig and says, “That’s the guy who drilled my well.” And this makes Hope Cemetery more than a place where people are buried—it’s a garden of stories. Each grave is a page in the Book of Barre.

My favorite monument in the cemetery was carved by Guiliano Cecchinelli. The stone is pre-need, meaning there’s no one buried beneath it yet. The person who bought it saw it on Cecchinelli’s lawn, where he’d been carving it, and asked to buy it. Made from a ragged waste piece of granite, it features a couple wearing long coats. As the woman leans into the man, the man wraps his arm around her shoulder affectionately. They could be lingering on a moonlit street on a chilly night, taking comfort in each other’s company and the forest-covered mountains before heading back inside.

On the grass in front of his home, Cecchinelli is carving another monument. This one is a five-foot-tall chunk of rock featuring a man, and a woman, and a dog. “It’s me and my wife and Isha,” Cecchinelli says, the last being their brown mutt. Each figure faces a different direction and though each is distinct, right now they are all clearly part of one shared thing, part of each other. The trio seems to be an animation of the monolith itself.

Forget that old adage “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” the piece seems to say, suggesting instead it’s merely: people and stone.

My grandfather and his brothers, my father and some uncles and some cousins worked in those quarries, the stone sheds or were in the trucking business trucking granite. My grandfather ended up for stay in that sanatorium and my father was sent to a preventorium because they were afraid he would catch TB from his father.

My dad and mom both arrived from Calabria, Italy. They met while my dad was working at Cross Brothers in Northfield, VT. I have a family photo dated 1910 showing about 40 Italian stone carvers with their families on a 3 day picnic just outside of Northfield. The men cut the trees and made the picnic tables and benches. My dad said almost every man pictured died in their 40’s due to silicosis.

Fortunately my dad lived till his 85th year. The Ambrosini family mentioned in the article was my great aunt’s maiden name. Her husband Emilio Politi started a granite cutting business. My uncle Emilio Politi’ s family and my father’s family moved to Peekskill, NY around 1916. Each of them opened retail monument business My father Stanislao (Stanley Tucci) was a master carver of details and letters. Interestingly he is the grandfather of the famous actor, Stanley Tucci.

Interesting story of lesser known history.

I remember an eloquent stone carving by a small Italian that was done years ago in his own likeness that rests on his grave. A masterpiece. I don’t remember his name. Then a few years ago some jerk vandalized that stone. I believe it was repaired. Brings back to mind what happened to Michelangelo’s Pieta, sad that people would do this. My wife’s father worked in the sheds as a blacksmith sharpening the tools.

Dear Julia, I enjoyed this article so much. I have a long abiding love of cemeteries and sculpture and admiration for the Italian immigrants who left enduring monuments to their presence in America. You brought them all together in this great article. Thank you! I know have Hope Cemetery on my “must visit” list!

I am left with so many thoughts after reading this piece. This is another look at the tremendous history that exists in New England. I wish my family members were resting in Hope Cemetery, I would feel that much closer to ‘touching them’.

Fabulous story; will definitely visit when back out again.

I’m working on my maternal grandmother’s genealogy and found that her father came from Sweden and was a stone cutter in Barre. He was lucky to live to be nearly 70. I find comfort to now look at any piece that came out of that quarry and think he may have been a part of it. Thanks for another great story of New England history. I’ve been a loyal reader for most of my 63 year old life.

I explored this cemetery in the 1980’s while selling silicone carbide to the industry for their wire saws. Only Barre Gray allowed but I saw the soccer ball and the couple sitting against the headboard in bed. Amazing art from the men who had their entire lifetime, however short due to silicosis (white lung disease), to make their own monuments. Beautiful!

Nice article and the story continues to be written in stone. The latest monument in Barre is located at Depot Square, and a tribute to the first boy scout troop in America being formed in 1909. It was based on a model by Carlo Abate, which was never completed due to his death. This monument was completed in 2018 and located in the very heart of Barre. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/67701