A Farmer’s Best Friend

When tending to patients that weigh at least half a ton, a country farm vet like Tom Stuwe must practice patience and kindness— and that’s just with their owners.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe morning of Good Friday 2016 was cold and damp, the colors of the central Vermont landscape a muted collage of grays, dull greens, and browns. The falling precipitation was either rain that was almost snow, or snow that was almost rain. An undecided day in an undecided season. I rode in the passenger seat of a Chevrolet pickup truck piloted by Tom Stuwe, a 67-year-old large-animal veterinarian who has been driving these graveled roads for nearly 40 years, the back of his truck loaded with the tools of his trade: medications and lotions, scalpels and syringes, a portable x-ray machine, and, most ominous, a medieval-looking castrating implement attached to a cordless drill.

Just before 8 a.m., we swung left and began to climb a steep, frost-rutted hill toward a dairy farm where a Jersey heifer labored futilely to deliver her first calf. After a few minutes, the farm came into view: low barn, listing sawdust shed, two New Holland tractors parked at odd angles in the barnyard. And mud. Lots of mud.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

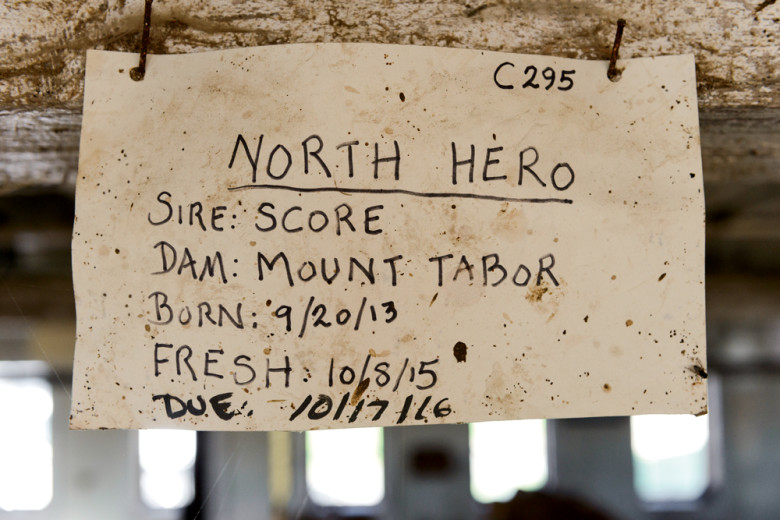

The interior of the barn was neater than I’d expected. The concrete floor was covered in a fresh layer of sawdust, and the cows—tawny Jerseys, mostly—were clean and, to use the parlance of the trade, in good flesh. Three young calves lay in the wide aisle between the two rows of milkers. Knotted-together lengths of baling twine ran between the calves’ collars and the ceiling’s framing members, and I was reminded of trellised tomatoes.

We found the heifer on her side, two small hooves protruding from beneath her tail. She’d been struggling for a couple of hours and was clearly exhausted; the farmer—his name was Ben—had been attempting to pull the calf, but those efforts yielded little progress.

We tried to compel the heifer to stand, first by pushing and yelling. When that didn’t work, Stuwe zapped her with a battery-powered prod. She rose briefly, then went back down and was disinclined to try again. Ben unhitched her, and we dragged her into the aisle for better access. Stuwe stretched out across the floor and slid an arm deep into the heifer’s birth canal to reposition the calf while Ben braced his boots against the heifer, trying to hold her in place. When the calf was positioned to Stuwe’s satisfaction, he wrapped pulling chains around the protruding feet and he and Ben heaved. Once. Twice. Three times. On the fourth pull, the calf slid onto the barn floor.

—

When my sons were young, they loved being read stories from a series of books by James Herriot, the nom de plume of James Alfred “Alf” Wight, a veterinarian who practiced for decades in the British countryside beginning in the 1940s. We read those books over and over again, all of us captivated by Herriot’s wry wit, his obvious respect for the farmers of the Yorkshire Dales, and his compassion for the animals he treated. Later, after we’d been through all of Herriot’s printed work, we happened upon the BBC’s All Creatures Great and Small television series, and thus passed many happy winter evenings.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

There is something inherently fascinating to me about the work of a large-animal veterinarian. For one, there are the beasts themselves, which to most of us are lumbering and mysterious, unable to communicate their ills in language we can understand. For another, there are the keepers of the animals, the men and women (and sometimes children) who are in many cases as dependent on these creatures as the creatures are on them. As Herriot made so delightfully clear, these are often people of unusual character and enviable wit in the face of hard work and ever-diminishing economic returns.

Finally, there is the simple fact that as family-scale livestock farming for meat and dairy continues its decline, the work of large-animal veterinarians is changing rapidly. This was true in Herriot’s day, as tractors and other mechanized technologies were replacing draft horses, and it is perhaps even truer now for Tom Stuwe, who increasingly finds himself tending to the pleasure-riding community. “My business has shifted from being 70 percent bovine and 30 percent equine to being 70 percent equine and 30 percent bovine,” he told me on the first day I rode with him. Of course, there are also pigs, sheep, and goats, and he’ll occasionally do the hard work of euthanizing a client’s ailing dog, but the majority of his patients weigh the better part of a half ton.

I rode with Stuwe for a total of five days over the course of three seasons, long enough to get a sense of the scope and rhythm of his work. I learned that being a country vet means spending a lot of time driving; Stuwe drives nearly 40,000 miles annually, pinballing across Vermont’s back roads, which he knows intimately (indeed, not once did I see him use the GPS feature on his phone). I learned, too, that much of Stuwe’s work is repetitive and not terribly exciting. For instance, during one visit he vaccinated 25 horses in a row, two straight hours of needle pricks. “Does it get monotonous? Yes, it does. But it gives me a chance to see animals I wouldn’t otherwise see, and sometimes that lets me pick up on problems the owners haven’t noticed.”

Stuwe is tall and just slightly stoop-shouldered, and he speaks in a calm, deliberate manner that conveys competence—which might have something to do with the fact that he’s accustomed to working with large animals, which he’s done since 1978. I first met Stuwe in the late 1990s, when he frequented the bicycle shop where I worked (he remains an avid cyclist and still completes 100-mile rides regularly); I got to know him a bit better when we started keeping livestock of our own and he became our veterinarian.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

But other than the handful of times I’d seen him tend to our animals over the years—an injured hoof here, a pregnancy check there, a cow that broke into a full bag of grain and gorged herself sick—I knew nothing about what it truly meant to be a large-animal veterinarian. And I was curious to hear about how his work had changed over nearly four decades of practice, in part as a result of evolving technologies, but also due to a rural landscape that is transitioning away from farms.

—

Tom Stuwe was raised in Michigan, and he retains just a whisper of that midwestern way of drawing out o’s, particularly when he says “OK.” His uncle Carl was a dairy farmer, but Stuwe did not spend much time on the farm, nor did his immediate family keep livestock, though he had a dog for most of his childhood. Stuwe was not a notably good student in high school, and in college he fared little better. “Basically, I flunked out of college,” he told me as we rolled along a remote gravel road (pretty much everything Stuwe told me was relayed as we rolled along a remote gravel road).

For a time, he hung his hopes on piloting commercial aircraft—he’d gotten his pilot’s license at the tender age of 17—but Stuwe was born with an essential tremor that causes his hands to shake subtly. The condition was inconsequential to his ability to safely pilot an airplane, and indeed he found a job flying corporate jets for Pepsi. Still, he was fired after an executive aboard the jet Stuwe was flying complained about the tremor, assuming it was caused by alcohol or drugs.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Thus began a challenging period in Stuwe’s life. He had recently married his girlfriend, Ruth (they are still married today), and the couple had a newborn daughter. He had no college degree, little future as a commercial pilot, and few prospects for supporting his new family. Plus, it was winter, and the economy was in recession. So he did the only logical thing: He bought a snow shovel and started knocking on doors near the East Lansing apartment they called home.

“After being a pilot, it was such a downer,” Stuwe recalled. I was mildly surprised to hear him admit this; although it was only the second time I’d ridden with him, already I’d become accustomed to Stuwe’s low-key but relentless optimism, which seems rooted in a well-cultivated sense of gratitude. The word blessing peppers his speech with some frequency, and here he turned to it again. “But going through that period of asking people if I can shovel their driveway for five bucks was a real blessing. It altered my whole perspective, and made me really appreciate work.”

He appreciated the snow shoveling but not enough to make a career of it, so Stuwe applied to Michigan State University with the ultimate intention of earning a veterinary degree. Poor grades from his previous schooling, however, were an impediment to acceptance (“And they accept everybody!” he told me), and Stuwe was compelled to enroll in junior college to bolster his record. One of his classes was organic chemistry, the passage of which required solid scores on three tests. On the first test, Stuwe earned a D. On the second test, another D. “I thought to myself, ‘It’s over,’ but I wanted to at least do something positive, so I read one review chapter before the final test.” He picked the chapter at random, out of dozens of chapters; it was the academic equivalent of a Hail Mary touchdown pass, and Stuwe knew it. But when he turned the test over on his desk, he found that the questions had been lifted straight from the single chapter he’d reviewed. “It was incredibly improbable,” he said. He looked over to me to be sure I understood what he was saying. “It was such a blessing.”

Eventually, Stuwe made his way to veterinary school with the intention of becoming a small-animal vet (according to the American Veterinary Medical Association, 67 percent of veterinarians in the U.S. practice exclusively on small animals). But one day during his senior year, the school brought in none other than Alf Wight (aka James Herriot), who was touring to promote his latest book.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Later that day, Stuwe found himself sitting next to the famed author at lunch. At one point during the meal, he asked Stuwe: What are you going to do? “I told him I was going into small animals, and he just looked at me and said, ‘Why?’ It’s amazing how one person can change your life in two minutes.”

It should be said here that Tom Stuwe is a Christian—not that being a Christian is unusual, but it seems clear to me that his faith plays a profound role in his relationship with both man and beast. He believes that humans sin, perhaps inevitably, but he also believes in forgiveness, both at the hand of Jesus and also in our more earthly relations. During our time together, we spoke at length of forgiveness and empathy, and the steady, seemingly intractable erosion of these qualities in contemporary America.

In Stuwe’s view, Christianity serves as framework for guidance in a world that is occasionally wicked, and often confounding in its unfairness. “Sometimes it feels like I fix these animals, and they live a little longer, and then they’re dead anyway,” he said. “Sometimes you know you’ve done everything right, and things go bad no matter what you’ve done. In the past, I dove into things where nobody else would touch the animal because it was dying anyway. I don’t do that so much anymore.”

Perhaps for good reason: In 2010, the British journal Veterinary Record stated that veterinarians are four times as likely as the general population to commit suicide and twice as likely as those in other health care professions. “You don’t think the euthanizations are wearing you down,” Stuwe told me, “but they are. You start to wonder what you’re doing.”

—

Tom Stuwe knows what I suspect every good veterinarian knows: The job is 10 percent animal and 90 percent human. This ratio is variable, of course: Farmers who rely on their stock for income generally need less hand-holding than, say, a family who keeps a couple of horses for weekend trail rides. But there is a human component to almost all of his calls, including one of the first I attended.

It was mid-April and raw; I’d arrived at Stuwe’s home at 6:45 that morning. He was already in action, dispensing medication to a dairy farmer whose calves were scouring (a term for diarrhea in bovine, a common affliction among young stock that are subject to the physical stress of weaning) between arranging his day’s supplies on a workbench in his garage.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

With his truck stocked and the farmer’s taillights disappearing down the road that leads from Stuwe’s home, we set out for a small hill farm about 30 minutes to the south. There, we walked across a winter-browned pasture; the ground had thawed and partially frozen again, and it felt strangely buoyant under our feet. A large dog trailed behind us, limping, her gait disturbed by the tumor in her back. It was a big and bulbous tumor, plainly visible to the naked eye, at least the size of a softball. Still, she trotted along gamely.

“She’s putting on a good show for you,” the dog’s owner said. His name was Eric.

Stuwe nodded. “They often do that.”

We walked another dozen steps or so. Stuwe laid down his supplies and prepared the injection that would transition the dog into death. “I commend you for doing the right thing,” he said to Eric. There were tears in the corners of Eric’s eyes. He patted the dog softly as he cried.

I saw the syringe in Stuwe’s hand and turned away. It was quiet for a short period, then I heard Stuwe speak. “I’m so sorry for your loss,” he said. We retraced our steps back across the pasture, stopping briefly at the truck before continuing across the road to a small livestock barn. It was just a few minutes after 8 a.m.; already Stuwe had euthanized a beloved pet suffering from untreatable cancer. Now it was time to remove the testicles from a year-old bull.

—

Stuwe’s work provides him with unique insight into humans’ relationships with the animals under their care. Sometimes, this insight fills him with hope, as with the obvious love and respect between Eric and his dying dog. And sometimes, it fills him with despair, as with every time he must appear in court to testify on behalf of mistreated animals: half-starved and nearly frozen horses, or dogs held captive in crates, bedded in their own feces. “The human mind is fascinating to me, why people do what they do. A lot of times, people say, ‘If only I had this, I’d be happy.’ But it doesn’t usually work out that way.”

Thanks to the hands-free mobile phone in Stuwe’s truck, I was privy to both sides of the conversation during the many calls he received while driving (his phone rarely stayed silent for more than 15 minutes at a stretch). Often I was struck by the extent to which these conversations veered from the particulars of animal care and into more personal terrain.

Late one afternoon, Stuwe received a call from a dairy farmer inquiring about the mastitis test results from a cow he hoped to purchase. But within three minutes, the conversation had shifted. “We’re really tight on cash right now,” I heard the farmer say. “I’m scratching my head, saying, ‘How’s this gonna work out?’” Stuwe murmured in a sympathetic fashion. “We’re losing lines of credit,” the farmer continued. “I talked to the bank, and they’re saying we should still be OK, but I don’t know.” Stuwe murmured again.

“That man’s 50 years old, living in a mobile home with eight kids, and trying to borrow $500,000 to buy a farm when milk’s at $14,” Stuwe told me afterward (he was referring to the price of milk on the commodity market, which is priced per 100 pounds; it is generally accepted that it costs the farmer about $17 to produce 100 pounds of milk). “He’s a hard worker, but I don’t know if that’ll be enough.”

We continued on to his next visit, where he bred a mare with a straw of semen that cost more than $1,000.

—

The next time I saw Stuwe, he was walking with a noticeable limp, the result of a broken fibula in his left leg, which he’d suffered when a horse had spooked and trampled him. “It’s a lot better,” he said when I remarked on the injury, which he’d x-rayed himself utilizing the portable machine he uses in veterinary work. He continued hobbling around his garage, collecting the medications and equipment he’d need for the day’s appointments.

After being trampled, Stuwe had taken a handful of days off, but he quickly returned to a full schedule. Although the demand for large-animal veterinarians is declining as dairy farms go under and new technologies reduce the need for in-person calls (for instance, cows can now be checked for pregnancy with a mail-in milk sample rather than a physical examination), the supply of large-animal vets seems to be declining even faster, perhaps because the finances are so marginal. Sure, Stuwe charges $120 an hour for a call, which seems a pretty penny until one considers the many unpaid hours he spends driving each day, along with the approximately $300,000 it costs to complete the required schooling. “There’s not much money in large animals anymore,” he said. “Everything’s changing so fast. I understand why no one wants to be a farm vet anymore.”

I asked if his injury had compelled him to consider his retirement. He nodded. “I already think about retirement all the time,” he replied. “I’m ready.” To this end, he recently took on a partner, a 36-year-old woman named Emily Comstock, who’d grown up with horses and accompanied Stuwe on his rounds when she was just 12. “I really want it to work out with her,” Stuwe said. “It’s not easy. This is a male-dominated profession, and she’s got a lot of debt from school. But I think it’s going to work. I really do.”

—

Last call of the day. A dairy farm in central Vermont, a cow off her feed. We entered the barn through a barrage of cluster flies, into the sweet smell of silage and the warmth of all that bovine flesh. The cow was lying down, but she rose quickly when prodded—a good sign.

Stuwe donned a long rubber glove and ran his arm into the cow, extracted a handful of manure. Examined it. “This is an easy one,” he said, sounding pleased. “It’s reticulitis.” Reticulitis is an injury to the reticulum, the first chamber in the alimentary canal of ruminant animals, and as Stuwe explained it in detail I suddenly realized where I’d heard of it: in an episode of All Creatures Great and Small, in which it had also been called “hardware disease,” since it’s often caused by a cow ingesting a piece of metal, maybe a scrap of old fencing, or the broken tip of a cutter blade lurking in the lush summer grass.

But this time it was small pebbles that Stuwe recovered, scraped from the ground with a loader full of feed. “This has a good ending,” he told the farmer, a 50-ish man named Frank who bore the deep back-of-neck creases caused by prolonged sun exposure. “She’s going to be just fine.”

We pulled out of the barnyard. Stuwe was grinning ever so slightly. “I like it when things end well,” he said.

Thanks for this insightful article on Tom Stuwe. I have used his services for our horses and formerly goats for decades. Our farming community is lucky to have him.

This is the most wonderful article, made all the more enjoyable because I know Tom and his wife as they were high school classmates of my sister here in Michigan. I plan to share this with his high school chemistry professor, who I am sure will enjoy it immensely!

When he made a visit to our Randolph Center dairy we could always be sure of not only highly competent veterinary services but also wonderful conversation. As is often the case, behind every successful man is a woman, in Tom’s case, his intelligent, supportive and very competent wife. You did a great job capturing a piece of Tom’s life. Thank you

Great story. Remarkable that he is still practicing. Large Animal practice is a lot of wear and tear on the body. Our large animal vet is in his 50’s and says most of the large animal vets he went to vet school with have already retired….

Beautifully written, Mr. Hewitt.

This is a wonderful article, so well written, and with the fine photos really tells the story of Tom’s compassionate work with animals and their humans.

I was a high school classmate of Tom and Ruth. It’s really great to see such a fine article. Tom is truly a man of character.