Rhode Island

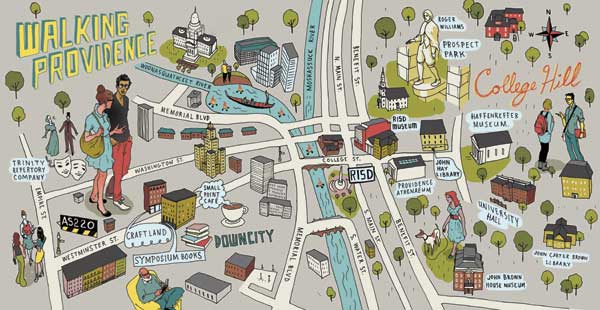

Walking Tour of Providence, Rhode Island

On a walking tour of Providence, Rhode Island, you’ll encounter famous museums, historic homes, an Ivy League campus, and possibly even ghosts.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanYou look like someone who appreciates a good story

- Unlimited access on the web

- Watch episodes online

Already a subscriber? Sign in