We’ve all experienced the euphoria that washes over you at the beginning of a vacation to somewhere new — a little town or village tucked away in a sweet corner of the region. You pick up the real estate digests stacked at store entrances; you linger in front of the fliers posted in agency windows. At breakfast on the second day, you turn to your traveling companion and announce, “We should move here.”

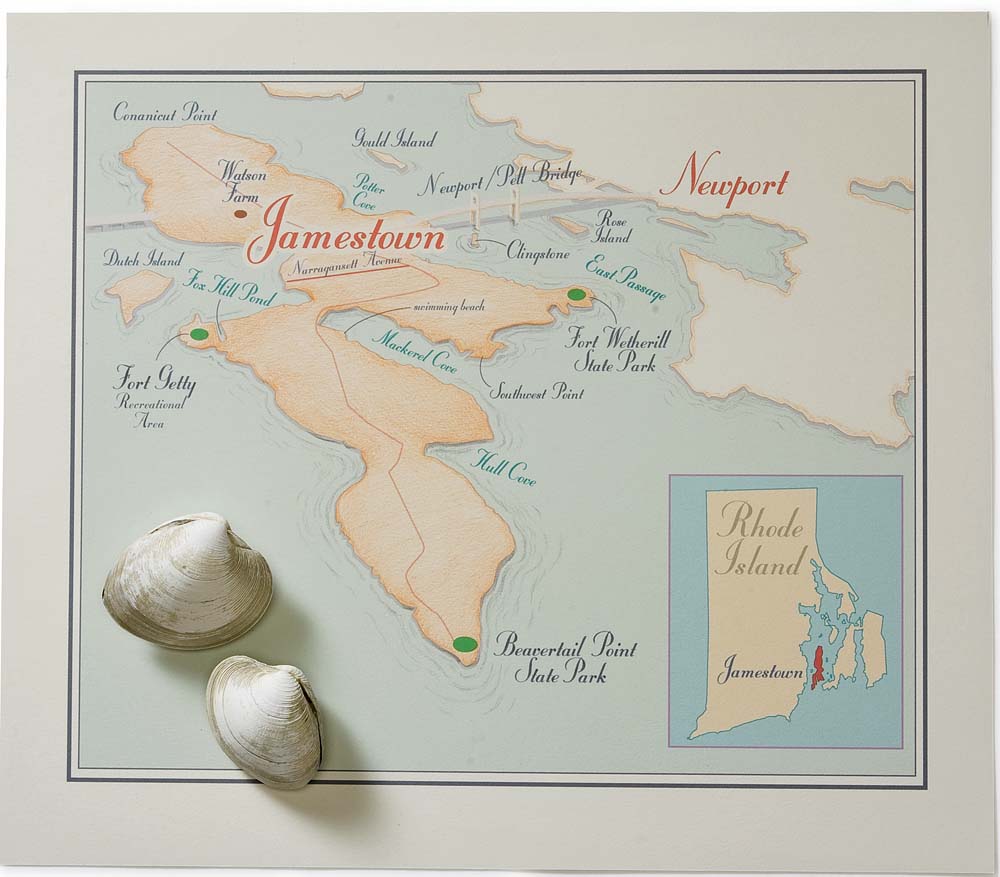

The spell usually wears off when you get home. But there are some exceptions to that rule, and one of them is Jamestown, Rhode Island, on Conanicut Island at the mouth of Narragansett Bay. This sleepy village presents a striking contrast to Newport, its bustling, high-profile neighbor to the east. With a population of 5,600 — one of the smallest of the state’s 39 towns — Jamestown is both a residential community and a seaside resort that doesn’t feel like one, even at the height of the summer season.

At the turn of the 20th century, Jamestown was predominantly a summer resort frequented by the wealthy, accessible only by ferry and with several grand hotels lining the waterfront. Today, elements of its resort past mix easily with its newfound residential character — helped, in part, by well-controlled waterfront development that has left large tracts of shoreline accessible to the public. One such beach is part of a two-mile trail system encircling

Watson Farm, a 285-acre working farm operated by Historic New England (formerly the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities), with the aim of preserving some of the town’s original rural character. Be sure to take a turn on the big swing hanging from the towering poplar tree in front of the 1796 farmhouse.

Across the road, the 1787 windmill near the Quaker Meetinghouse further attests to the island’s rural past and its role as a supplier of the white cornmeal that goes into Rhode Island’s famous jonnycakes. Climb to the top of the turret to take in a dramatic view of the

Claiborne Pell (Newport) Bridge soaring over the East Passage.

The 9.5-square-mile island of “Quinunicut” had already been inhabited for thousands of years when a group of colonists purchased it in 1657 from Narragansett Indians. The first regular ferries began running less than 20 years later and remained the only way to access the island until well into the 20th century, when the Jamestown–Verrazano and Newport/Pell bridges were built — a development that some residents still mourn. “Well, we’re attached to the world now,” says Carol Todd, a docent at the

Jamestown Historical Society on Narragansett Avenue, which hosts an ongoing exhibit about how the bridges changed life on the island. (Narragansett Avenue, which also holds the hardware store, post office, fire station, pharmacy, marine supply, deli, local bar, and most of the restaurants, is the cross-island connector and the heart of downtown.)

Although the bridges transformed Jamestown into a bedroom community for cities as far away as Providence and Boston, the island is still relatively isolated by modern standards, but only physically.

New York Times delivery boxes can be spotted in front of scores of homes dotting the island, many of which are historic or older single-family residences on large lots, interspersed with newer developments.

If you’d rather rent than buy, try T

he Bay Voyage — an inn so-named because it was ferried across the bay to its current location on Bryer Point Beach, where you can all but pull your kayak up to the reception desk. The inn is a short walk up Conanicus Avenue from East Ferry, where Narragansett Avenue meets the waterfront and the

Jamestown & Newport Ferry docks (be sure to stop at

Rose Island for a tour of the lighthouse.) Spend the morning here browsing the boutiques, shops, and galleries. Sit with a coffee on

East Ferry Market & Deli‘s brick patio overlooking the harbor, or grab a picnic lunch for your day-trip.

Kayaks may be rented behind the dock master’s office for a paddle around the harbor or perhaps out to Clingstone, the famous, but private, “house on the rocks.” Later in the day, grab an ice-cream cone at

Spinnaker’s and catch one of the many free evening concerts at the waterfront park. Complimentary on-street parking and the proximity of public restrooms at the community recreation center make it all easy.

If you have access to cooking facilities or are camping at

Fort Getty Recreational Area, keep heading north to

Zeek’s Creek Bait & Tackle for some of the freshest seafood in the state. While there, take in the view of Great Creek, where local clammers rake the muddy bottom searching for quahogs. Just north of Zeek’s you’ll find birdwatchers setting up scopes at

Marsh Meadows, where the Audubon Society has erected a perch for nesting osprey, which sail, swoop, and dive over the wetlands in search of fish.

On the southern half of the island you’ll find Mackerel Cove, the only swimming beach on the island. Spend the day here and line up at Del’s frozen-lemonade truck, an iconic fixture in the parking lot. If you’re in town for the Fourth of July, take in the fireworks show, launched roadside from the beach.Continue on to

Beavertail State Park at the southernmost tip of the island — the best place to watch the sunset, as well as the sailboats gliding in and out of the bay. Visit the lighthouse museum and the small aquarium, or watch surfcasters face the salty spray of the Atlantic in hopes of hauling in a giant bluefish. Fishermen and others congregate on the rocks below the foundation of the 1749 lighthouse (the first in Rhode Island and third in the country), which was lost until it was revealed again by the scouring waves of the 1938 hurricane.

Near day’s end, scramble down the rocks to claim a spot among locals and fellow travelers alike. In your own private crevice or cove, everyone else falls from sight, letting you ponder what it might be like to live here, as you enjoy the brilliance of the sunset.