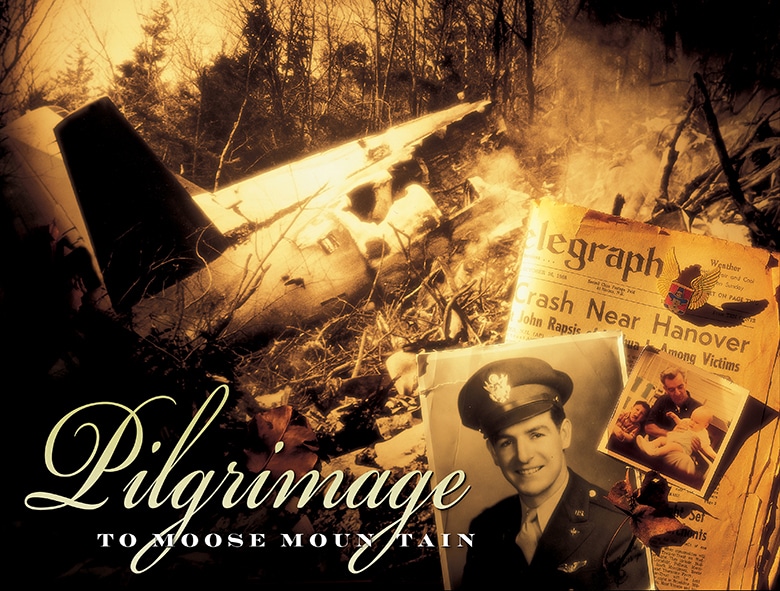

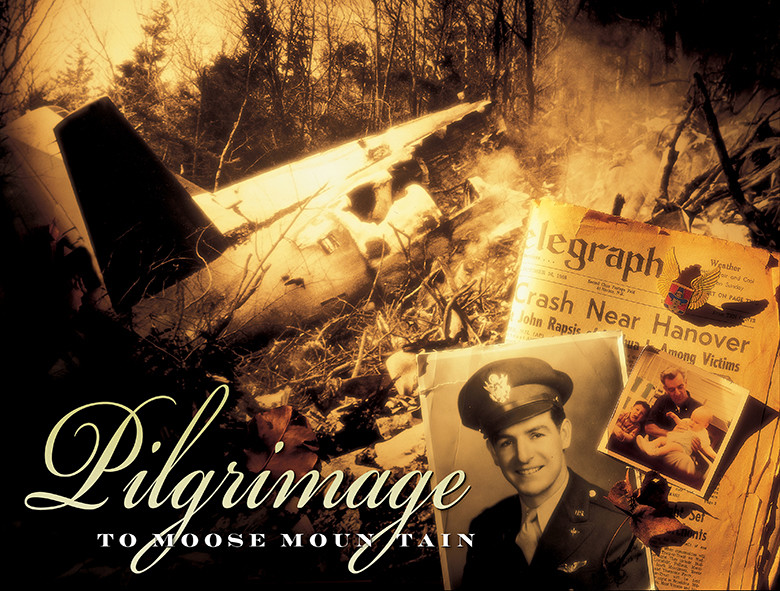

Pilgrimage to Moose Mountain | Yankee Classic

Classic Article by Jeff Rapsis We’re just below the summit of South Peak on Moose Mountain, near Hanover, New Hampshire. It’s a 45-minute hike in from the nearest road. The morning sun glints off a misshapen scrap of metal sticking out from the ground. It’s a piece of twisted aluminum, half buried and partly melted. […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Illustration by Doug Mindell

Classic Article by Jeff Rapsis

We’re just below the summit of South Peak on Moose Mountain, near Hanover, New Hampshire. It’s a 45-minute hike in from the nearest road. The morning sun glints off a misshapen scrap of metal sticking out from the ground. It’s a piece of twisted aluminum, half buried and partly melted. It juts up from the ledge like a strange metal weed.

This remote stretch of steep ground is the location of the worst aircraft accident in New Hampshire history. It happened 30 years ago, when a Northeast Airlines plane with 42 persons onboard crashed into rocks right here, about eight miles northeast of Lebanon’s airport, where it was supposed to land.

Ten survived. But 32 were killed, including my father, who was the pilot.

It’s a cool New England fall afternoon, a Friday. At Logan Airport in Boston, a Northeast Airlines prop jet lifts off and flies northwest. Daylight fades as the plane, a Fairchild-Hiller FH-227 painted in the airline’s new yellowbird colors, flies north of Lake Sunapee, then curves southwest to approach the Lebanon, New Hampshire, airport.

Looking out windows, passengers see steep wooded hillsides through breaks in the clouds below. The plane’s No Smoking sign winks on in the cabin. Clouds break again. Passengers see the treetops are closer now, whizzing past below, closer and closer. The land rises up alarmingly.

The plane grazes the treetops, which catch it, slow it, and then begin to tear it apart. The left wing snags on a large tree, pulling off the rear of the fuselage and the tail, which lands upright on the steep mountainside.

The rest of the aircraft plows into the trees, breaking apart on the rocks and bursting into flames.

The date is October 25, 1968. The time is 6:17 p.m.

I was four years old when it happened. I don’t remember anything about it, nor do my two brothers, who were five and one. It wasn’t something that our mom liked talking about when we were growing up, either.

Most people say, “Leave the past alone”—and with good reason. Why spend time thinking about some terrible event? And that’s especially true in the case of some random accident like the plane crash, which proved no point and offered no obvious lesson.

It was a pure accident, by the way, though investigators put pilot error in there as one of the causes, as they always do.

What happened was this: The plane was being guided by radio signals to the end of the runway, and weather conditions were just right for the signals to start bouncing around the hills. That caused the plane’s navigation instruments to give the flight crew some bad readings, which is why the aircraft came down too soon and hit the mountain.

Pilot error? They may as well blame it on voodoo or witchcraft. Or fate, whatever that is.

The plane grazed the east slope of the 2,294-foot mountain and then crashed just 37 feet below the summit. That’s the height of a not-so-tall tree.

Think about that.

Donald Crate, fire chief of nearby Enfield, is at home. The phone rings. It’s Bradley Hollis, a town resident, saying he sees a fire up on Moose Mountain.

Crate drives as far as the town ball field, where he sees what looks like a small brush fire high on the mountain. He drives back to the fire station and calls the Hanover fire department, which is also checking on fire reports.

Crate then turns on his radio and learns a plane has crashed. He immediately sounds a general alarm, one of many that night that bring teams of fire, police, and rescue workers to the mountain.

Though memories are scarce, some scenes endure: I recall one time my mother went food shopping after the crash. She had gotten all the way to the checkout counter when she found she had a box of Dutch Masters cigars in the basket. That was my father’s brand. She had to take them back, though she didn’t tell anyone why.

At the time of the crash, my father had just started building an addition to our house in Nashua. So there was my mother, with three young kids and eight unfurnished rooms, braving the long winter of 1968-69. Remember that one? It snowed three days straight in February.

Even a kid could tell it was a mess. I remember snowdrifts piling up over stacks of fresh lumber. And when it was finally finished later on, the house leaked for years.

Clues that something happened can still be found today. I look at old photo albums, and I see tons of snapshots of my brothers and me right up to just before Halloween 1968. The pictures stopped then and didn’t really start up again until we were all three or four years older.

And in the barn, a vintage Ford Model A molders away under a layer of stepladders, tarps, and other debris. My father tooled around in that thing for years, but the driveshaft cracked sometime in that last summer, so he put it up on blocks for the winter. It hasn’t moved since.

My older brother has the same name as my father. Five years ago, he checked his credit rating for the first time in his life and found that all my father’s old accounts had somehow wound up on his report, unchanged from 1968.

Darkness comes quickly, but the area around the crash is a jumble of shadows cast by the orange glow of the blaze, which grows in the minutes after the crash.

Robert Kimball, 44, assistant dean of the business school at Dartmouth College, regains consciousness in the wreckage. Kimball, a passenger in the rear of the plane, is still in his seat but not surrounded by flames.

His one thought: Flee the fire. He climbs out of his seat and into the bough of a tree. He then falls some distance—he’s not sure how far—to rocks below.

Though we all put the crash behind us, my curiosity remained. A few years ago, I called an office in Washington, D.C., to get an accident report on a plane crash in Vermont. It was for a story I was writing.

Without quite thinking it through, I asked if old reports were available. I told them the date and location of my father’s crash, and a couple of weeks later a large envelope came in the mail. Inside was a fat report on the accident, complete with my father’s autopsy report.

Among other things in there was the exact location of the crash, which old news accounts I’d seen made seem remote enough to have been in the Yukon. But I still didn’t think seriously about going up there until six years ago, when events seemed to push me in that direction.

Other survivors escape the burning plane through a rear door opened by flight attendant Betty Frail, who signed on with the airline four months before the crash. She breaks a leg in the accident but also survives.

Stumbling over rocks and wreckage, Robert Kimball finds a few other dazed survivors gathered downslope from the debris, which now burns more intensely. Among them is Dr. Richard Veech of Oxford, England, who landed upside-down in a tree, still strapped in his seat.

Though Veech has a broken back, he marshals the group and keeps them going. He instructs Kimball and another man how to prop him up correctly, then tells others how to treat those in shock.

Veech then tells Kimball and the other man how to pull out one victim, who is still alive but pinned under a heavy tree.

Several people who live through the crash die from injuries. With the fire still spreading, the survivors struggle down the steep slope. It’s dark. It’s cold. A drizzle is falling.

It’s August 1992. I’m at the Delta Airlines ticket counter at Logan Airport in Boston. Just for the heck of it, I ask if anyone there once worked for Northeast Airlines, which Delta bought out in 1972.

Turns out a bunch of them had, including a few who had worked with and remembered my father. My timing is good. Former Northeast workers are throwing a reunion party in a couple of weeks at the Commodore banquet hall in Saugus, Massachusetts, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the date the airline went out of business.

I go. It is a huge affair, and almost everyone there seems to have known my dad. That is weird because, after all, I didn’t. So I listen to stories I’d never heard before from flight attendants and pilots he worked with—even from the guy who loaded the bags on the last flight.

With fires burning on the slope above them, survivors wait. A plane is heard overhead. Soon the shouts of men are heard through the trees.

Just before rescuers arrive, an explosion erupts in the wreckage, most likely a fuel tank igniting. It lights the steep mountainside with an orange glow and sends a small mushroom cloud toward the dark, wet sky. Flaming debris tumbles among trees down the mountainside.

The first rescuers find an unbelievable scene, lit by fire but shrouded in smoke. Flames lick mangled aircraft metal, which softens and drips into puddles like wax among fallen trees and engine parts. Bodies lie dismembered on rocks, with the plane’s triangular tail still intact, rising into the treetops.

I didn’t know how hard it would be to get near the site or if we’d find anything there. It would take a well-planned expedition and some serious bushwhacking to ever find it, I figured. Most of the wreckage was lifted out by helicopters years ago so investigators could look it over.

I took the coordinates in the report and plotted them on a topographical map. The site turned out to be about two miles off a service road leading to a communications tower on a nearby peak.

From the road, dotted lines led through the woods and up to South Peak, where the plane hit the mountain. Dotted lines meant trails, but as anyone who has hiked the woods around here knows, lines on maps don’t always correspond to what is there.

Anyway, I didn’t feel like trying my luck climbing around a peak named Moose Mountain during hunting season, so I waited. The best time to explore would be early spring, after the snowmelt and before green-up, I figured.

Winter passed. And early one overcast Sunday morning, I found myself and a friend driving up the steep grades of Moose Mountain Lodge Road, not knowing quite what to expect.

Survivors able to walk guide the first rescuers to the severely injured. As others watch, a local doctor, Richard B. Baughan, works on a young woman who lived through the crash, but she dies on the mountain.

After being stabilized, survivors are then carried out by rescue crews down a trail and then a logging path to Moose Mountain Lodge Road. The work is slow, with teams often having to stop after just a short distance.

Donald Crate Jr., the Enfield fire chief’s son, and Dwight Marchetti use clothing to wrap Betty Frail’s feet for the walk down the mountain.

The service road to the tower is blocked by a heavy metal bar, so we park at the lodge and walk. We reach a sharp bend where the trail should be, and sure enough, it’s there, complete with a sign and directions.

We hike in. It’s easy going, though we sometimes sink into wet patches. The ground is bare. Remains of snowdrifts linger on in areas of shade.

To my surprise, the trail improves as we rise. We meet another trail, and a sign tells us the paths have names—the Blue Diamond, Pure Delight, and so on. We just follow signs. It’s like going to a yard sale.

There are no clues to what year it is. The forest makes no allowances for fashions, styles, or fads. For all I know, it’s 1968 again. Around the next bend might be men carrying someone on a stretcher.

It wouldn’t surprise me.

October 26, 1968. It’s dawn. Light grows, fills in the darkness between fires still burning on the mountain. It reveals an ashen landscape, a mountainside festooned with scorched passenger seats, blown-apart sheet metal, and flaming brush.

Those who survived the crash are in Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover. Those who didn’t remain on the mountain.

Bodies are placed in plastic pouches and brought up to the summit one at a time. Brush is cleared off a flat area on top so a helicopter can land. Bodies are then flown to a makeshift morgue at the National Guard armory in Lebanon.

Relatives begin to arrive. The Hanover Inn is used as a reception point. Only one victim is identified the first day.

On the mountain, investigators hunt for key parts of the plane. Before noon, they find the flight data recorder in the still smoldering aft section of the plane. It is intact, though burned so badly it is still warm to the touch 18 hours after the accident.

Some of the tape is fused together. It’s rushed to a laboratory in Washington, D.C., where it is put into an alcohol solution to loosen it. Later it is unwound and read.

About 2:00 p.m. they find the cockpit voice recorder, which tapes any conversation in the cockpit. It is charred and pitted by fire. Inside, the tape is melted.

We trudge up the trail. It is overcast. Leafless branches fissure a slate sky. The trail follows the crest of a ridge, which fills the landscape in front of us and rises slowly until it crests at the summit.

The mountain is flat on top. There’s no tree line, but the summit is partially cleared on the east side, where the accident site should be. The clouds lift enough for us to see east, into the valley below.

We rest. I check the map, still not certain we’re even on the right mountain. I then walk alone through low bushes to the edge of the cliff on the peak’s east side. An ill-defined path goes down among rocks and small trees. I grab a branch and lower myself to the first rock.

Watching where my feet fall, I notice what looks like an odd shard of mica. For a moment I think it is just another piece of litter, but I stop.

I pick it up. It’s not trash. It’s a piece of metal no bigger than a poker chip, scorched and tarnished as if roasted under a blowtorch. And then I notice on one edge rivets like on a ship.

My heart sinks. This is it. This is where it happened.

It’s Sunday, two days after the accident. Only seven bodies have been positively identified. The rest are burned so badly that authorities must use any clue available—earrings, wedding bands, clothing, and finally dental records—to identify them. Up on the mountain, a team of ten investigators collects evidence. Large parts of the wreckage are lifted off the peak by helicopter and collected for testing. Police continue to patrol the area. They keep busy turning back hundreds of sightseers and souvenir hunters.

At some point in the ensuing week, they all leave. Soon winter claims the mountain, pulling a blanket of snow over the scorched rocks.

I see a strip of black fabric on the ground. It is part of a safety belt that survived the postcrash fire. I pull at it. Part of it underground disintegrates, and it comes free in my hands.

Rock by rock, we hop down the mountainside, holding onto trees. The slope is steep. If there’s anything left up here, we should run into it not too far down.

And yes, a little farther down, it’s clear something happened here. Badly decayed tree trunks are strewn over the rocks. Standing trees are small, none of them older than the accident. Sides of boulders are burned with red and orange tones, as if fired in a kiln.

On the forest floor, junk is everywhere, mostly scraps of aircraft aluminum crumpled to look like pieces of paper. We’re not quite ready for what we see—struts and funny rocks that turn out to be gobs of aluminum that melted, then cooled. The gobs were sometimes imbedded with intact bolts, like a sheet metal nut cluster.

Between two rocks I find a woman’s shoe. Moss is growing on it. I don’t pick it up.

Spring comes, and snow melts. On the mountain, the forest reasserts itself, covering the black scar of the crash with a fresh crop of green. Tiny shoots of weeds and grass appear, bringing life from the ashes of the scene of so much death.

And in the minds of those touched by what happened, the needs of daily life reassert themselves, covering the memory of the crash with concerns about what’s for lunch and what’s for dinner.

I think to myself that this place is significant because of all the lives that were changed here forever. Though it’s possible to say that every place and every action has significance, there’s no way to know for sure. But here we can know. Think of the families, the lives that were changed forever because of what happened here. Think of the impact.

With that in mind, places like this are apart from the rest. This place, on the side of a mountain, changed my life and the lives of dozens, hundreds, thousands—it’s impossible to say how many.

I am what I am today because of what happened here. I know this to be true. And it’s comforting, oddly, in a world that’s a web of uncertainty, to be so sure of something.

On the mountain, a shard from a smashed coffee mug carried on the plane is buried by the leaves of many autumns. The sun travels across the sky thousands of times before its light catches on part of the white ceramic mug still visible through the mulch.

I notice it and pluck it from the ground. I will bring it down the mountain, and I think to myself, I’m glad I came.