Where Winter Is Grand | New Hampshire’s Grand Hotels

With breathtaking landscapes, casual luxury, and storied pasts, New Hampshire’s grand hotels let visitors make the most of this — or any — season.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Susan Pease/Alamy Stock Photo

On my eighth or ninth throw, the double-bladed ax stuck smartly in the third ring from the bull’s-eye, a three-pointer.

It was a brisk January day at the ax-throwing venue behind the Mountain View Grand, a stately and improbable survivor of a time when you hardly could have thrown an ax in the White Mountains without hitting a sumptuous resort hotel.

Back then, these big wooden arks would never stay open in the winter. In the steamer-trunk, lamb-chops-for-breakfast era, rusticating in the White Mountains was strictly a summer business: It was all about rocking on the veranda, changing outfits for each meal, playing a game of bridge in the parlor, and perhaps getting in a round of golf or a few sets of tennis. Those short, sedate seasons—along with changing styles of travel, as railways gave way to the automobile—doomed most of New Hampshire’s grande dames.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Mountain View grand

The Mountain View was among the doomed—for a few decades, anyway. I first stumbled onto the place, located roughly 10 minutes south of Lancaster, in Whitefield, about 10 years after its 1986 closing. I’d never seen anything so big that was so derelict, yet somehow clinging to survival. Vandals, I decided, must be in short supply up this way.

What I was looking at was the oldest grand hotel in New Hampshire, one that had started out less than modestly and grown to four-storied, twin-towered magnificence over 60 years and eight additions. As the story goes, on one stormy night in 1865, a Montreal-bound stagecoach turned over on a badly rutted road, leaving its passengers with no alternative but to seek shelter at a farmhouse owned by William and Mary Dodge. When the storm cleared in the morning, the stranded travelers marveled at the mountain vistas. Their suggestion that the Dodges open an inn led to four generations of family hotel-keeping, and to the expansions that would bring the Mountain View House, as it was originally known, to its present size by the 1920s.

The photos in the hotel’s History Room amply chronicle those halcyon days. Here’s Warren G. Harding, out on the links, sporting a bow tie. There’s Dwight D. Eisenhower, another of the seven U.S. presidents who sojourned here, grinning his big Ike grin while relaxing with the Dodges. Vintage menus recall a time when no resort stay was successful if you went home without putting on a few pounds. The images show a world that was all suits and sundresses and long afternoons in wicker chairs. There’s also a melancholy reminder of the coda to the Mountain View’s own long afternoon: the auction catalog from the final dispersal of its contents in 1989.

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

Massachusetts contractor Kevin Craffey was just as surprised as I had been when he discovered the shuttered behemoth in 1998. He met the asking price-—a scant $1.3 million for the hotel and 1,700 surrounding acres—and four years later reopened the hotel as the Mountain View Grand. He even tracked down and bought back many of the furnishings that had been snapped up at the auction (the carved eagle above the reception desk is just one original artifact). Perhaps most remarkable of all, amid renovations that included removing seven layers of wallpaper and replacing almost 1,000 windows, was the restoration of the building’s original cedar clapboards, painted the same sunny yellow as before.

Craffey knew that a White Mountain resort hotel could no longer survive on a May-to-October schedule. The trend among North Country travelers had evolved away from leisurely summer stays of weeks on end, and toward shorter visits packed with activities, as well as new concepts in indoor luxury at any time of year. Along with winterization of the rambling structure came cross-country skiing and snowshoeing; snowmobile touring; an indoor pool; a barn with sheep, goats, llamas, and alpacas for kids to visit … and ax-throwing. “Use both hands and give it a few practice swings, overhead, before you let go,” I was instructed by my coach, Elaine Frenette, of the hotel’s activities staff. I did as I was told, tried to remember Kirk Douglas’s technique in The Vikings, and got my three points.

But since you have to throw axes without gloves, and it was barely above zero that day, I soon opted for one of Elaine’s daily treks around the remaining 400 acres of the property. From the trail, I could look back at the hotel, flags flying from the towers, a yellow ocean liner beached in the snowy mountains.

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

In one of those towers, one flight up from the spa, I would discover the Mountain View’s ultimate modern indulgence: an infinity tub for two, surrounded by four picture windows. It’s available by reservation, and staff will send up champagne or whatever other potable you desire. Looking from tub to view and back again, I thought of the old-time clientele, who I suppose would have been no more likely to sip champagne in an infinity tub for two than to throw an ax.

Those folks did like to eat (as the old menus attest), but they never could have imagined the shape the hotel’s premier dining spot would take today. The 1865 Wine Cellar is a subterranean retreat where racks of wine, thousands of bottles, take up every bit of wall space. “I’ll seat you in the Nook,” the maître d’ said, as he led me to an inner sanctum. I’m told the Nook is a popular spot for marriage proposals, but it’s also a fine place for a solo diner to read labels between courses, thinking about how little time, how many bottles….

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

—

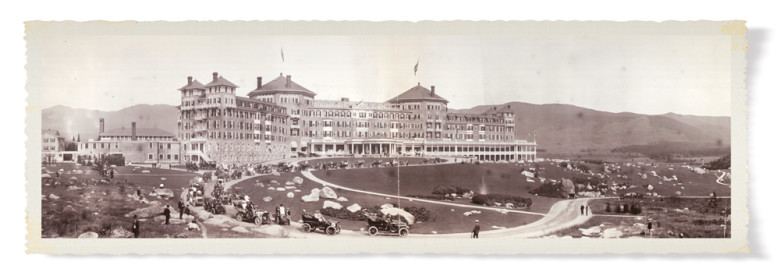

Half an hour down the road from the Mountain View stands the giant of New Hampshire’s grand hotels, the once and perhaps still largest wooden structure in New England: the Omni Mount Washington.

Having grown up in so many stages from its farmhouse roots, the Mountain View still has an air of hominess about it. The Mount Washington, though, was raised to its gargantuan proportions all at once; grandeur, rather than hominess, was its guiding light. I’ve never entered the place, beneath its 23-foot lobby ceilings, without sensing a Gilded Age aura, and though I’ve never circumambulated the entire wraparound veranda, I know that if I did so six times, I’d have walked a mile.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Joseph Stickney was a coal broker when the world ran on the stuff. He owned the Mount Pleasant House, which stood across the road from where the Mount Washington sits. At the turn of the 20th century, he decided to build something on a grander scale. Architect Charles Alling Gifford designed an immense Y-shaped palazzo in a Mediterranean Revival style, and 250 Italian workmen, brought over specially, finished the hotel in less than two years. It was 1902, and White Mountain resort habitués had never seen anything like it: electric lights everywhere, and a bath for every room.

Summer saw 35 trains a day stopping at the nearest depot. Horse-drawn carriages brought patrons, their copious amounts of luggage, and sometimes even their maids and valets to Mr. Stickney’s hotel, set majestically on a gentle rise before the apron of land that spreads toward Mount Washington.

Like all the old hotels, the big place shut down for the winter. There’s a grandfather clock in the cavernous lobby that once marked that annual cycle: Each year on opening day, in the spring, the first guest would start the pendulum swinging; on closing day, in the fall, the last one out would stop it.

Photo Credit : Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

But, with the exception of a two-year period in the early 1940s, the Mount Washington never closed altogether. One reason for its survival during the grand hotels’ declining years was its selection as the site of the 1944 United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, which met that July to hammer out the framework for a postwar world economy. More than 700 delegates from 44 nations, including such luminaries as Britain’s John Maynard Keynes and American treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., came here and established the International Monetary Fund and the predecessor to the World Bank. In a salon off the lobby, there’s an enormous round table at which the conference’s final agreement was signed.

Winter stays at the Mount Washington didn’t begin until 1999, when new owners finished a massive weatherization project and got ready for a turn-of-the-millennium gala. Since then the party has gone on year-round, given the hotel’s proximity to winter sports opportunities. Bretton Woods’ 97 alpine ski trails are just a few minutes down the road (like the hotel and nearby Bretton Arms Inn, the ski resort is owned by Omni), and shuttles run between the hotel and the slopes all day.

I left verticals for another day and set out instead for a turnaround part of the 62 miles of cross-country trails here. I didn’t have to head far into this forest maze to spy spectacular scenery. A highlight was the boulder-shelved, half-frozen Middle Falls of the Ammonoosuc River, which rises on the slopes of Mount Washington.

Photo Credit : Christian Heeb/Laif/Redux

Later in the day I followed a different snowy trail, and let someone else do the work—eight someone elses, to be exact. My shuttle dropped me off just as Scrappy, Ruby, and the rest of the Muddy Paws dogsledding team were hitching up. “They’re mostly a mixture of Siberian huskies and hounds,” musher Wes Guerin told me, “and many of the ones we use are rescues.” Like other sled dogs I’ve met, they were eager to go—but unlike many, they were as ready for petting and ear rubs as they were for business. As we took off, I asked Wes how he decided which dogs had the smarts and mettle to work in the lead. It’s mostly, he said, a matter of attitude.

I had a table in the main dining room on a not-too-busy night in the aftermath of a holiday weekend, and as I sipped a glass of wine between courses, executive chef Jacky Francois stopped by. He talked about how he had set the culinary tone for the hotel’s three restaurants; for this big formal room (jackets and ties no longer required, but, mercifully, no baseball caps), he emphasizes New England’s bounty. A perfectly done pan-roasted cod loin underscored his remarks. Chef Jacky used to teach at the New England Culinary Institute, and part of his job here is to train young chefs. When asked how he could tell which ones had potential, he said it was all in their attitude. Having heard a similar sentiment earlier that day, I realized that a prospective lead dog and a good trainee chef have something important in common.

On my last afternoon at the Mount Washington, I visited the spa for a hot-stone massage, and as the warmth turned my back muscles to butter, it occurred to me that if the delegates to the 1944 conference had each been able to spend an hour with my massage therapist, Pam, the world might have gotten a truly superb monetary system.

Photo Credit : Morton Larsen/Alamy Stock Photo

—

If the Mountain View Grand and the Mount Washington look like ocean liners beached among the peaks, New Hampshire’s third great Gilded Age survivor, Wentworth by the Sea, resembles one at its proper berth. Standing at the southern tip of New Castle Island, the Wentworth looks over the water in nearly every direction, and in winter it bathes in a Winslow Homer light.

Like the Mountain View, the Went-worth withstood years of dereliction. Built in 1874, it suffered a typical midcentury decline. After closing in 1982, it dodged a date with the wrecking ball, reopening in 2003 after a local preservation campaign—and a role playing itself as a spooky abandoned hotel in the 1999 Annette Bening film In Dreams. And like the Mount Washington, the Wentworth also hosted a historic conference, having been chosen by President Theodore Roosevelt as the site of the 1905 peace talks that ended the Russo-Japanese War and earned him a Nobel Peace Prize.

Photo Credit : Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

I checked in to the Wentworth on a bright, cold afternoon, when a cheery fire burned in the lobby hearth and Annette Bening couldn’t have found a spooky corner in the place. In the cozy bar-restaurant Salt, I relaxed over drinks with Stephanie Seacord, a local historian who was active in the 2005 centennial commemoration of the conference. “Roosevelt told the two sides they could negotiate face to face, and he wanted a quiet place,” she told me. “And as he had been assistant secretary of the navy, the closeness of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard appealed to him. That’s where the treaty was signed, although the delegates stayed here at the hotel. Another advantage was that Portsmouth’s émigré Jewish shopkeepers could speak Russian.”

Unlike the two upcountry hotels, the Wentworth occupies a mere four acres of its original 400-acre expanse. No matter: New Castle is only a 15-minute drive from Portsmouth and its lively, compact downtown.

Just after crossing into Portsmouth, I came upon a jolly winter scene. The painter I thought of now was Bruegel, rather than Homer: Here at Strawbery Banke, a preserved neighborhood comprising three centuries of period homes, children and adults were ice skating. I’d been on skates all of twice in the past 30 years, but when I saw there were rentals available, I couldn’t resist joining the fun … and after three circuits round the rink, I even let go of the rail.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Wentworth By The Sea Hotel

Relieved of the need to dutifully visit Portsmouth’s slew of historic houses (none of them stay open in winter), I poked around the city center using busy Market Square as my orientation point: Two upended cannons, captured by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie, flank the entrance to the Portsmouth Athenaeum and make a sort of milepost zero. Around the corner I found a bookstore, RiverRun, that sells vintage typewriters. Down at the end of Deer Street, I was confronted by a stark black wall that turned out to be the massive flank of a freighter, the Orient Dispatch out of Limassol, Cyprus, just nestled into its berth by a couple of the doughty tugs docked nearby—Portsmouth is a seafaring town still. A maritime feeling even pervades the town’s favorite music venue, the Dolphin Striker, a low-ceilinged old cellar with its entrance on a dockside alley. It’s the kind of place where you could picture a knot of salty dogs off a windjammer tumbling in, thirsty for grog.

Passing some half dozen coffee-houses—only one of which bore the name of Ahab’s first mate—I decided on lunch at the Portsmouth Brewery, where I had a richly satisfying bowl of curried mussels and a winter-worthy pint of brown ale. Nothing more than mussels, though, because tonight I had a reservation for one of the signature events of the Wentworth’s winter season. Every year, for a month that straddles January and February, the hotel holds its Winter Wine Festival. The weekly highlight is the Grand Vintner’s Dinner, a four-course affair in which each course is paired with a carefully chosen wine. “Actually, the dishes are selected to go with the wines, rather than the other way around,” explained the evening’s host, winery ambassador Cathy Harrison. Her team had chosen well: A cabernet from Alexander Valley, California, matched not only a hanger steak but also its cedar-planked parsnip accompaniment.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

After dessert—yes, paired with a wine—I toddled back up to my corner room, where the turndown maid had closed the blinds on the oversize windows. I opened them again. I wanted to see the first of that sea light, that Winslow Homer light, when I woke up at the Wentworth in the morning.

Mountain View Grand, 855-837-2100; mountainviewgrand.com.

Omni Mount Washington, 603-278-1000; omnihotels.com/hotels/bretton-woods-mount-washington.

Wentworth by the Sea, 603-422-7322; wentworth.com.

Loved the article on the Grand Hotels. My first job out of high school was at the Mountain View. Oh the memories….and because I’m a photographer a photo of the veranda from the Mount Washington Hotel graces my wall in my home in Virginia.

Loved this article. I’m glad these wonderful old hotels have been renovated and saved and are still in use. I hope the same can be done for old NYS resorts like Grossingers.

Still homesick for New England and Portsmouth, as a resident of Northern California foothills, I loved re-visiting these hotels in old photos and history. Thank you. Add some old recipes (or new) please, like the curried mussels. Thank you, Yankee.

Beautiful images!!

I love New England in the winter!

Mount Washington Hotel is wonderful year-round. The surrounding natural beauty and historic rooms make a delightful retreat.

I wonder if and hope that the Balsams in Dixville Notch will every experience rescue and revival. My husband and I stayed there several times before its doors closed — such a lovely setting.

About ten years ago I took my family to the Balsams and we loved our time there. Sad to hear recently that it may close.

I was a guest at the Dodge family’s Mountain View Hotel in the mid-19th century (in the summer). It was an extraordinary experience for me and my pal who was traveling with me. The Dodges were the ultimate managers of a property so large that it took a week to grasp its complexities. Don Dwight