Lessons of a Very Old House: The Rich Rewards of Colonial Craftsmanship

In restoring an antique Colonial using 18th-century techniques, it’s possible to understand a little more about your place in the world.

The home’s original details, such as this painted staircase, had been left virtually untouched over the course of its long life.

One summer day my car rolled down a winding road that followed the waves of the Atlantic in the town of Duxbury, on the South Shore of Massachusetts. Tossed stone walls rambled along windswept hills. Behind the walls stood solemn rows of wooden houses, their simple rectangular elevations backlit by the sun. Battered by salt air, weathered shingles had turned from the blond of fresh-cut cedar to a silvery gray, that way that locks of hair change color with time. The jumble of a construction site encroached upon one of the homes, a fine example of early American architecture. In front of it, leaning against a telephone pole, lay a stack of old windows. Beside them, scratched crudely on a torn piece of cardboard, bold black letters proclaimed “FREE.”

The wood from these antique window frames had come from old-growth forests. Tightly clustered together, the trees had grown slowly, competing for water, nutrients, and sunlight. That struggle made the wood dense, less prone to rot than trees that shoot up quickly from clear-cut ground, as in modern industrial forestry.

A joiner had planed the profile on the muntin bars, the thin strips of wood that form the grill within the window frame. Sleek and curvy, the plane iron itself mirrored the pattern that it left in its wake. Then the joiner fit the pieces together with mortise-and-tenon joints. Through a long hollow tube, a glassmaker had blown molten silica and spun it on a gaffer’s chair, like a throne, until the glass spread into a large disc. Its finished surface rippled with tiny grooves like a vinyl record. He cut the disc into small rectangular panes. From powdery chalk dust and cold-pressed linseed oil, a glazier mixed a doughy putty. He sliced a pristine bevel of it around each pane, securing the glass in place.

When properly maintained, these windows lasted for centuries. Knowing all the skilled work that had gone into them made leaving them on the side of the road anathema to me. To abandon them, like so much fly-swarming garbage, felt wrong. I pulled over and loaded them all into my car.

I understood the skills required, could count the hours of labor, because I’d learned to do what those long-gone workmen had done. My own house had taught me. Fortune had brought me into possession of a three-century-old Colonial that needed restoration. Hewing as closely as possible to 18th-century building techniques had taught me arduous lessons. But within them, hidden like a secret room, lay a deeper lesson. In understanding my house, I came to understand a little more about my place in the world.

It began with a book. Large and rectangular itself, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625–1725 by Abbott Lowell Cummings has a bright red cover like that of a children’s storybook. Given to me as a gift, it thoughtfully catalogs a handful of the earliest surviving houses in the Bay State, detailing exteriors and interiors, floor plans and framing. An entire chapter describes the builders and their resources. It immediately drew me in and compelled me to seek out these structures, one by one.

Most of the houses had survived and were operating as museums. My original interest focused on timber framing. As tour guides spoke about generations of occupants, my eyes fixed on the large beams that ran overhead, studying, analyzing, piecing together how the craftsmen had fashioned and assembled them. Months of poking around these ancient treasures convinced me that I wanted one of my own.

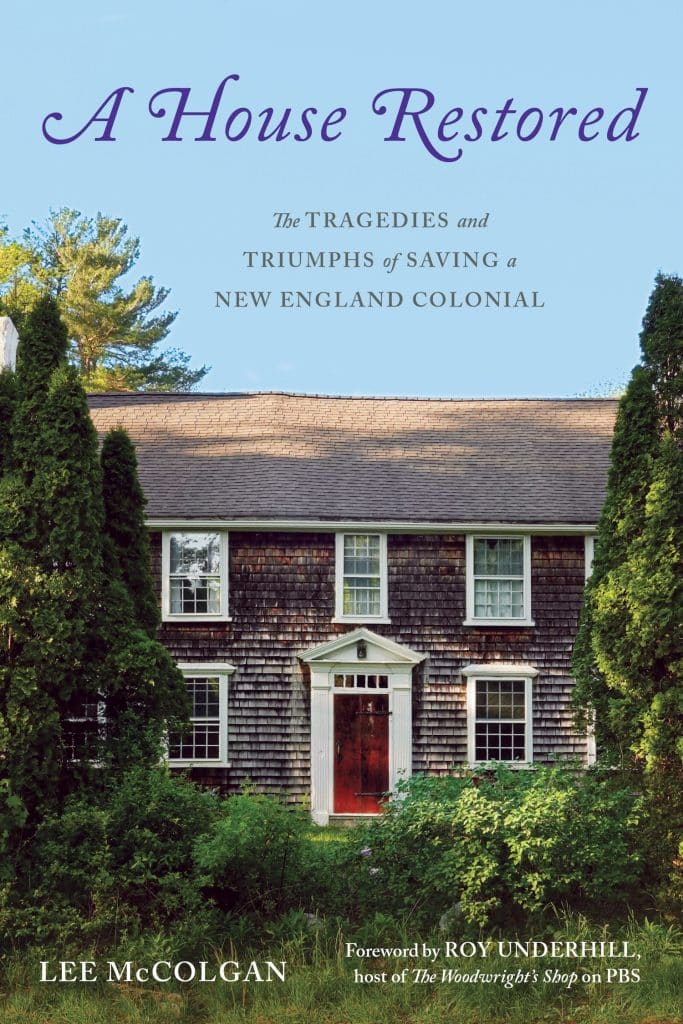

In 2017, real estate listings led me to the Loring House. Built in 1702 in what would become Pembroke, Massachusetts, it stood frozen in time. Most Colonials on the market have endured numerous remodeling jobs over the centuries, but not the Loring House. It felt like digging up a house-size time capsule buried deep in the earth.

The house clearly needed work, though, and I needed to figure out how to do it. In my research, an account of an 18th-century master builder named Richard Macy that I’d stumbled across in Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Away Off Shore provided my path. A passage in the book recounts Macy’s grandson writing: His practice was to bargain, to build a house, and finish it in every part, and find the materials. The boards and bricks he bought. The stones he collected on the common land, if they were rocks he would split them. The lime he made by burning shells. The timber he cut here on island. The latter part of his building, when timber was not so easily procured of the right dimensions, he went off-island and felled the trees and hewed the timber to the proper dimensions. The principal part of the frames were of large oak timber, some of which may be seen at the present day. The iron work, the nails excepted, he generally wrought with his own hands. Thus being prepared, he built the house mostly himself.

Builders—some skilled, some unskilled, some free, some indentured—lived hard lives. They toiled, raised families, and died in comparative obscurity, most now forgotten. But the simplicity of what they did appealed to me. A dozen basic hand tools could do most of the work. Richard Macy captured my imagination, and the decision came almost immediately: Following in those footsteps, I would restore the Loring House myself using period methods and materials. How hard could it be?

Like a mad scientist, I found out. I stumbled through acquiring tools and sourcing supplies. I tracked down living builders using traditional techniques to learn the tricks of their trades. I performed my own sometimes demented experiments with the materials to encourage them to yield to my demands. Through it all, house museums continued guiding the way. The more I learned, the more those relics revealed. After a summer working with a traditional plasterer, I saw anew the rich textures and details of walls and ceilings. In sections abutting wood or brickwork, where the plaster was crumbling, tufts of fur sprang from the chalky white material like coastal sea grass.

Blacksmiths had forged the iron hardware of latches, hinges, and door handles, heating them until they glowed orange and bent to their will like clay. Hammer blows flattened and fanned the metal into simple shapes—circles, triangles, rectangles, spades—that they finished with delicate file work. Where they had welded two pieces together, subtle lines called “peen marks” remained evident.

Swinging too close to the ground, my broadax once caught a small rock, nicking the blade. As it sliced through the fibrous cellulose of new wood, that nick left a small track in its wake, a tiny arch like a rainbow. The old wood in some of the house museums revealed similar marks. “That carpenter’s ax had a small nick in it,” I announced to no one in particular. Macy deserved far more credit for what he had done.

But as the restoration progressed, a simple question pulled at me. Why did it matter? Saving an old house doesn’t save lives. On a long-enough timeline, I will go, and so will the structure. Finding an answer to that deceptively straightforward question felt like trying to dislodge a splinter from my brain.

Our possessions reflect us. I began to understand what my house said about me. Living in an untouched three-century-old house was not ordinary, and this spoke to my eccentric nature. Working with minimally processed materials—wood, lime, stone, iron, glass, brick—held an allure, too. These materials live in better harmony with the natural world than most modern building supplies, full of petrochemicals and plastics that destroy untouched landscapes and eventually gorge landfills. On my watch, the Loring House would age with grace, but even when it finally crumbles beyond repair, its materials can return to the earth with a calm magnanimity. In its way, the house itself had become an environmentalist, too.

In the meantime, the work grounded me, made me happy. Our relationship, the house’s and mine, became symbiotic. It provided shelter for my family and me, and my efforts kept it standing and functioning as intended. In it, so many of the people in my life had converged. The hardships and triumphs of the restoration eventually made it clear that the work was less about the building itself than about all the people whom it had protected. It always had been. Beneath an old, weathered roof, we told new stories and made new memories to fill our own lives and others’. What better to do with our time than that?