Keys to the Past | How Tom Furrier Keeps the Typewriter Tradition Alive

In a small workshop in the Boston suburbs, Tom Furrier preserves history one typewriter at a time.

Tom Furrier wants to apologize for “the mess.” It’s a Friday morning in May, and Furrier is trying to explain the setup of his shop, Cambridge Typewriter, a tight, shotgun-style space in Arlington, Massachusetts. Metal shelves, tables, and even the floor are lined with typewriters of different vintages—some 300 in all. A narrow path between the stacks of machines leads to Furrier’s desk, which backs up to a cabinet of obscure parts and is itself a home to a rare Chinese typewriter holding 2,500 different characters.

A tall man with a thatch of brown hair that hangs over the tops of his ears and wearing a pair of square, dark-rimmed glasses, Furrier takes a seat at his desk and surveys the scene. “It’s not always like this, but”—he shakes his head—“we’ve been busy, and trying to keep up with everything has been a challenge.”

But today will be a quiet one—few calls, even fewer drop-ins—which will allow Furrier to anchor himself in the back workroom, where he hopes to finish reconditioning a 1950s Corona Zephyr. It’s a cramped space that Furrier has put to creative use. A back shelf overflows with boxes of rollers and other typewriter parts, including the carcasses of a few junked machines. In the adjoining bathroom, a stack of IBM Selectrics resides next to the toilet.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

To call Cambridge Typewriter just a shop misses the point. In a metropolitan area that was once filled with businesses devoted to typewriter sales and repair, Furrier’s is the lone survivor, and one of the few of its kind left in the Northeast. After first coming to Cambridge Typewriter in 1980, when it still resided in Cambridge, Furrier took over as owner a decade later. And in one sense, he is a fix-it and sales guy: restoring treasured machines for some clients, finding obscure ones for others. (Even reminders of Furrier’s once-robust service calls still occasionally occur, thanks to the handful of government and law offices that continue to rely on typewriters.)

But in another sense, Furrier is both a curator and the embodiment of an analog experience that thrives as a contrast to the touchscreen world outside Cambridge Typewriter’s walls. Furrier rarely uses a computer and only reluctantly began carrying a cellphone. A landline receives the shop calls, every one of which he logs with pen and paper. A record player, often playing jazz vinyl, provides a steady soundtrack, while the tools of Furrier’s trade are a collection of obscure mini flathead screwdrivers, scissors, and hooks.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

“When people come here for the first time, they do kind of marvel at the place,” says Furrier. “What I do, how I operate, what this place looks like—it’s a throwback. But then as soon as someone gets their fingers on a typewriter, there’s something that also feels comforting. Young people, especially, tell me all the time: There are no distractions. You can’t multitask. You have to zero in and concentrate. And you have to carefully pick and choose what you write.

“And then you’ve got the sensory feedback from the typewriter itself,” he continues. “The rhythm of the typewriter kind of meshes with the speed of your thoughts coming out of your brain. They work together, and that’s something you’re never going to get from a computer.”

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Furrier’s expertise in—and shared enthusiasm for—these old machines has led to close ties withtypewriter-loving authors such as Tayari Jones and the late David McCullough, as well as a collaboration with Errol Morris for his 2017 miniseries, Wormwood. Furrier himself has been the subject of a short documentary. He marvels at the worlds he’s entered. “I would carry Mr. McCullough’s typewriter around like I was holding a baby,” he says. “He wrote all of his books on it, and I kept thinking, If I do something to it, that’s going to be really bad.”

But now Furrier is ready to step aside. He turns 70 next year, and recent health issues have sped up his retirement plans. This past spring, a sale that had been three years in the making fell through, leaving Furrier scrambling to find a new buyer. He’s asking just $35,000, a price that includes his tools and not just all the machines he has on-site, but also the several hundred others he has at home. If he can’t sell the shop by the end of the year, he may simply close it for good.

“I love what I do, but I also don’t want to croak at my bench,” he says. “I’ve got stuff I want to do. My wife and I want to travel. We want to spend time with each other. But to just close it up and not see it continue would be the worst possible outcome. That would haunt me.”

* * * * *

Shortly before noon, a woman named Donna steps into the shop clutching an Underwood Five, a bulky machine that was the dominant typewriter for the first few decades of the 20th century. Furrier springs to his feet to clear out a space for it.

“I’m so glad I found you,” says Donna, who drove up from her home on the South Shore. “We spoke on the phone not that long ago.”

Furrier takes a seat in front of the machine and begins to look at it. “You wanted a tune-up, right?”

Donna nods. “This was my mother’s,” she explains. “She’s 98 now, and her parents gave her this when she was 16. They were living in Braintree and her father bought it in Boston. He carried it all the way home on the train. It’s so heavy—can you imagine?

“We’ve had it in my house, and my grandchildren thought it would be a fun thing to play with.” She shakes her head. “We’re not going to allow that anymore. I don’t want anything to happen to it. It’s so beautiful.”

Furrier runs his hands over the side panels. “This is all original,” he says admiringly. “It’s from before they went to a single panel.”

He looks up at Donna. “Give me about a month, and I’ll have this nice and shiny. Just like brand-new.”

About a half hour later, a longtime customer named Tom arrives to pick up a similar Underwood, built nearly a century ago, that Furrier has refurbished. “It’s going to have a home in our 1932 house in New Hampshire,” Tom says with pride. He rattles off the seven other machines he’s bought from Furrier over the years. “We’re using them, too—they’re not just showpieces,” he adds. “I have kids in high school and college and always tell them, ‘If you want to add an interesting touch to something, you can’t go wrong with a typed letter.’”

Furrier smiles. “That’s what I like to hear.”

The presence of a typewriter shop may seem like a minor luxury for a downtown. But something valuable is lost, says typewriter historian Richard Polt, when niche expertise is strictly relegated to chat rooms and YouTube. That’s especially true for anyone seeking refuge from the digital mayhem and the growing presence of artificial intelligence.

“You can still find typewriters online very easily, and you can find people online who you can send your typewriter to, and so on,” says Polt, a professor of philosophy at Xavier University in Cincinnati and author of the 2015 book The Typewriter Revolution: A Typist’s Companion for the 21st Century. “But having a physical spot like Cambridge Typewriter where somebody still practices this work, which just seems more and more magical every day—that’s irreplaceable.”

Others agree. Last year, Tom Hanks, whose collection of typewriters numbers north of 250, sent Furrier a signed machine as a thank-you for the commitment to his craft.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Furrier’s obsession with the mechanical began early. The oldest of seven kids, he grew up in Wakefield, Massachusetts, under the guidance of parents who encouraged his love of tinkering and learning how machines worked. Lawn mowers and other small engines held particular fascination for him. “I loved fixing stuff and bringing them back to life,” he says.

Furrier also loved the outdoors, and he would go on to study forestry at the University of New Hampshire, even working in the woods briefly after graduating. But in 1980, a family friend named Ed Vanderwalle, who’d opened Cambridge Typewriter 12 years earlier, asked Furrier if he’d like to work as a repairman.

“He said, ‘Come in for a week to try it out and we’ll see what you’ve got.’” Furrier laughs. “I never left. At the end of that first day, I bonded with it. There was this voice in my head that said, This is what I’m going to be doing. This is going to be my career. I just connected with it. I got the whole vibe of it, the laser focus you need to do the work. It all sunk in.”

Nobody knew it then, of course, but the typewriter era was in its waning days. By the mid-1980s the personal computer had taken hold, and in 1986 Vanderwalle laid off his entire team, even his son, except for one: Tom Furrier. Four years later the owner sold the shop to his protégé for $25,000, and Furrier relocated Cambridge Typewriter to Arlington.

Over the next decade, business only got leaner. By 1999, Furrier could barely keep the lights on. “I’d resigned myself to the fact that this was it,” he says. “I’d even started taking watch-repair classes, thinking that was something I could do. But, I don’t know, this feeling came over me. That I needed to hold on. Don’t close. Something is going to change. I didn’t know what, but I needed to stay open.”

A few years later, Furrier still had his doors open, just barely, when he started noticing a new kind of customer: high school kids. They’d ask questions about his machines and want to test them out. Furrier was baffled.

“There were these girls from Lexington High School who kept coming in to ask about a very specific model of machine. I finally said to them, ‘Why do you want that typewriter?’ One of them just looked at me and said, ‘That’s the machine Sylvia Plath typed her poetry on, silly.’ And it all clicked for me in that moment. There was going to be this resurgence of interest. This was how it was going to work for me.”

In a typical year, Furrier sells around 150 typewriters and repairs about 700 more. Plenty of them are the electric Smith Coronas and IBM Selectrics that were always a staple of his work, but many others are the antique manuals that have caught the attention not just of Furrier’s new generation of customers—a third of his buyers are under the age of 40—but also of the shop owner himself.

“Until then, I didn’t have any typewriters at home,” says Furrier. “It never even occurred to me to type on these things—I fix them all day, why would I want to use them when I’m not at work? I wasn’t working on these old manuals. But then everything changed and I had to learn about them. I’d practice, taking them apart on my bench and putting them back together again and again. They’re a different animal than the [electric machines] I was used to. They have a different vibe, and you kind of resonate with them. I quickly became a fan.”

* * * * *

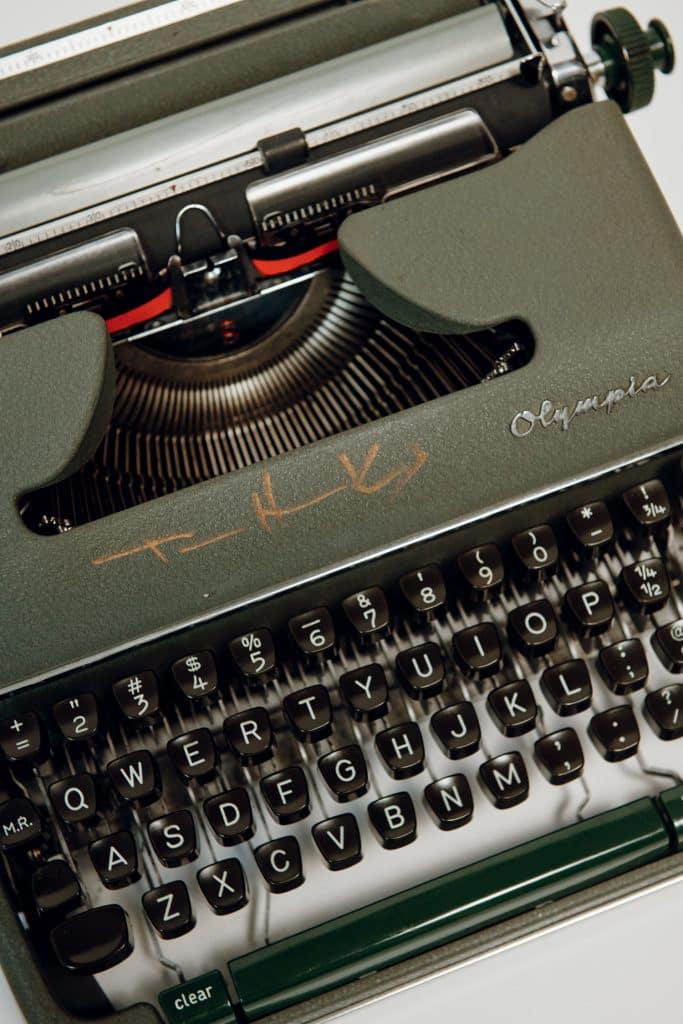

Furrier’s own admiration for these machines has grown alongside his customers’, and a walk-through of his shop is a tour of some of his favorites: the West German–made Olympia SM3 from the 1950s, the Swiss Hermes models from the 1960s, and the American-built Corona Fours.

“I love the clunkers from the 1920s and ’30s because they’re slower, they’re awkward, they’re noisy, and they have that classic clicky-clack sound,” he says.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

In most cases, the machines find him. Long gone is the time when Furrier had to scour flea markets and yard sales to bolster his inventory. Now, on any given day he’ll receive up to six calls from people who are downsizing or cleaning out a parent’s estate and who have an old typewriter that needs a new home. Some simply donate it to Furrier; others he’ll pay as much as $100 for their machine—and the opportunity to spend a good half day stripping and reconditioning it back into working order.

In doing so, Furrier is also helping bring the stories of these typewriters back to life. The portable Royal that a World War I soldier carried into European battlefields to file his reports. The Folding Corona used by the late golfer and writer Francis Ouimet. The Underwood favored by journalist Paul Mowrer, who won the 1929 Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence.

On a few occasions, visitors to the shop have shared with Furrier how typewriters have touched their life—or even saved it. “One guy had tears in his eyes when he was telling this to me because most of the unit he was in [during World War II] got wiped out,” says Furrier. “But he’d been yanked at the last minute because he knew how to type and they needed him in the clerk’s office.”

Those stories may be what Furrier misses the most when he walks out of his shop for the final time. Which is why whoever the next owner of Cambridge Typewriter is, they must carry an appreciation for what those stories mean. Furrier says it’s as important to running the business as having the skills and patience to work on the machines themselves.

“If you’re into typewriters even just a little bit, this is heaven,” he says. “The coolest people on earth use typewriters today. People who are doing really interesting things: artists and musicians and writers. They all have cool stories. You get to hear those stories, and that’s the best thing about this job. You could write a book about it all.”

Preferably on a typewriter.

To inquire about purchasing Cambridge Typewriter, call Tom Furrier at 781-643-7010 or email him at info@cambridgetypewriter.com.