Home and Away | Maine Photographer Greta Rybus

Spanning cultures and continents, Maine photographer Greta Rybus finds the threads that tie us all together.

Ever since Rybus moved to Maine in 2011, she’s found endless inspiration in its rugged and beautiful landscape. In this image, taken on assignment for the state’s tourism office, she shows what Camden Harbor’s iconic Curtis Island Lighthouse looks like from inside a lobster boat’s pilothouse.

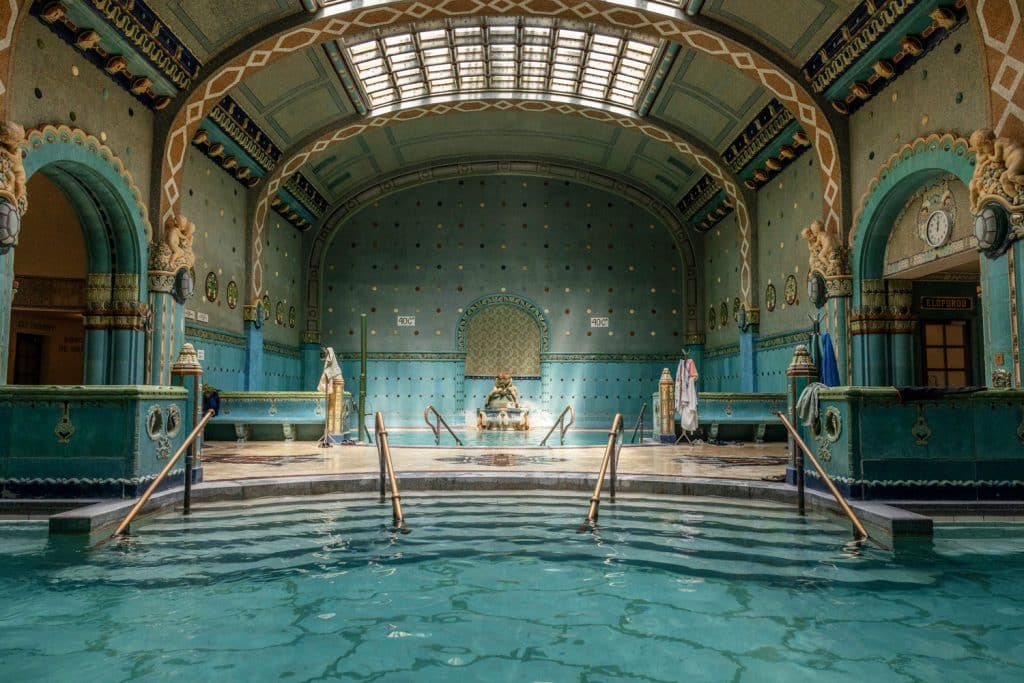

Photo Credit : Greta RybusWhen talking about a photographer, we often refer to their “eye,” as if what is seen through their lens explains what emerges for us as viewers. And the photos you see here certainly reflect the keen and restless eye of Greta Rybus, whose work has often appeared in Yankee as well as in many other publications. And with her brand-new book, Hot Springs (Ten Speed Press), her eye takes readers on a world tour of 14 countries. “Hot springs have helped shape the culture of these places—what does that look like?” she says.

But to understand the depth of Rybus’s work, you need to know as much about her heart as her eye, and how she is inspired to show how people care for their places, and each other.

Raised in the Mountain West with stints overseas, Rybus came to Maine after college to intern for a Portland photo agency—the only work offer she had received. “I fell for Maine, how its landscape could be both harsh and nourishing,” says Rybus, who still lives in Portland today.

As a freelance photojournalist, she carries versions of the same cameras she used in college. “I want to think about equipment as little as possible,” she says. “I want to think about the experience.” And the breadth of her experiences is vast, from immersing herself in the world of wild sheep and the Mainers who care for them, to capturing the haunting moments of a home in Senegal being washed into the sea—an event, she says, that changed her life and spurred her desire to show climate change not as an abstract concept but as a burning reality.

To make her delicately beautiful landscapes and portraits, she strives to find intimacy and empathy with her subjects. “I’m asking people to be vulnerable” to what she calls “an interview with my camera,” she says. What she learns with her heart shows up in her eye, and we feel them both.

To see more of Greta Rybus’s work, including a preview of her new book, Hot Springs, go to gretarybus.com.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen