Remembering Russ Morash: The Man Who Revolutionized How-To TV

When it came to building a new genre of television, “This Old House” creator Russ Morash went DIY all the way.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan“Russ Morash, 88, died after a brief illness on June 19, 2024.”

I still can’t quite believe I’m writing that, having hung out with Russ and his wife, Marian, for this article only a few months before. That day, he’d been the same inimitable, avuncular, irascible, confident, brilliant guy I’d known since we’d met in 1980, when I was 19 and working as a busboy in the Nantucket restaurant Marian had co-created, and he was 44 and had just launched This Old House, the show that would cement his reputation as a television pioneer.

A few years later, having graduated from college and working in Tokyo but wanting to live in Boston, I wrote to Marian to see if I could talk to Russ about a job. There was at that time precisely one full-time position on This Old House. It happened to be open, I got it, and I spent the next 17 years producing the show.

During my last visit to his house, Russ and I reminisced about our adventures from that time together. Highlights included shooting a scene atop the north tower of the Golden Gate Bridge, interviewing the Lady Chablis from Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, and helicoptering over an active volcano in Hawaii—all in addition to the dozens of house renovations we followed step by step through sun, rain, and snow, all across the country.

Along the way, we’d had most of the struggles a boss and a right-hand man can have. But we had put all that behind us years ago: He’d retired, I’d left the show, and we’d formed a brothers-in-arms friendship that glowed warmly as I interviewed him. My unsolicited advice: Stay close to the people you’ve shared the journey with, because you never know when your paths will diverge.

* * * * *

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

There’s an on-brand memento as soon as you enter Russ and Marian Morash’s renovated 1851 farmhouse: a framed black-and-white photograph that shows the building back in the old days, long before they bought it in 1974. It’s a classic “before” to the “after” they’ve built in a long series of improvements, like a six-decade episode of This Old House. The house, the workshop out back, and these two acres of New England soil have been background and foreground to three iconic American how-to television series—The Victory Garden, This Old House, and The New Yankee Workshop—supplying the visuals and content for at least two generations’ idea of the right way to grow, cook, and build.

In fact, it’s safe to say that without this slice of Lexington, Massachusetts, the entire genre of how-to TV would have looked a whole lot different—if it had come into being at all. That’s because Russ, now 88, essentially invented the concept, and if he’d stayed inside the studios of his employers at the Boston public broadcast station WGBH, he might have spent his career differently. Joining the fledgling station as a cameraman in 1961, the Boston University theater major cut his teeth on public-interest shows like The Advocates, but it was his work with Julia Child on The French Chef that planted the seeds for what was to come.

Starting with omelets and beef bourguignon, showing how things get done step by step turned out to be his passion. Voice-overs, lots of edits, and other production fripperies didn’t interest him—as in theater, the immediacy of a long scene seemed right to him. “You want to do it real,” he says.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

When he started a show about gardening in 1975, that meant turning a patch of greensward next to the station’s loading dock into a 75-by-75-foot working field. When that garden became a popular stop on station tours, he and his bosses knew he was onto something. And when Russ saw a guy measuring the plot and found out it was because The Victory Garden would now be charged on a square-foot basis for use of the land as a studio, Russ knew it was time to decamp. He had his own land.

“You can’t know it till you grow it!” Russ would say. The talented plant people he employed—Jim Crockett, Bob Thomson, Roger Swain—helped him turn his backyard into a laboratory to show everything from how to build a cold frame to how to brew manure tea. A greenhouse came next, crucial to keeping a New England garden going and, as important, to extending the production season.

As the crops poured forth and the station started getting letters asking How do I cook that vegetable I just saw?, it was time to enlist Marian. A self-described home cook, she brought a cheerful you-can-do-it spirit to the screen, whipping up dishes in the Morash kitchen (which Russ and his father had built from scratch in their basement) and not leading with the fact that she was also head chef at a renowned Nantucket restaurant in the summer months. The unerringly useful Victory Garden Cookbook she published in 1982 has sold more than 350,000 copies.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Back at the old photo, Russ points to the rear ell of the house and describes how they kept the roof but removed everything else, rebuilding the structure to accommodate their growing family. Daughters Vicki and Kate grew up in this house, though Vicki was born when the Morashes lived in their first place, a modest cottage a few streets away. There, when the excavator Russ had hired for a new addition’s foundation broke down, he dug it himself, by hand. His father had been a house builder, and Russ wasn’t afraid of hard work—nor was he averse to the cost savings that come from doing things yourself.

Thrift is in his blood. “All the plywood we used here,” he says with some pride, “it came from the John Hancock Tower.” (When its windows began popping out during construction in the mid-1970s due to a design defect, the landmark Boston skyscraper removed all 10,334 of them, with their temporary replacements earning it the nickname the Plywood Palace. After new windows went in, the 20 acres of used plywood then went on sale for a buck a sheet. Russ pounced.)

A guy with a reverence for the past—victory gardens hark back to the world wars, houses are more interesting when they’re old, and Yankees have been in New England from its beginnings—Russ was equally focused on the new. Despite coming out of the theater world, he embraced the new technology of television, and he made sure his shows limned both tradition and the latest and greatest gizmos.

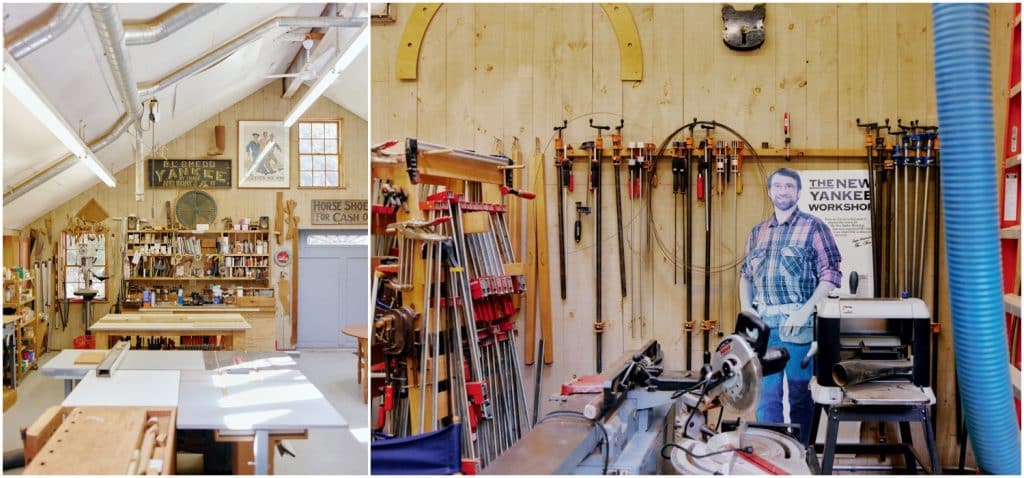

Lexington was his palette, a media-age working farmstead. The outbuilding that This Old House master carpenter Norm Abram built, in part to hold garden equipment for The Victory Garden, went on to be the set for the Abram-hosted The New Yankee Workshop, a mesmerizing mix of old-school craft and cutting-edge woodworking machinery, the shop brimming with laser-guide miter boxes and a table saw whose blade stopped the moment a finger touched it.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

A big European beech tree was transplanted in the yard when The Victory Garden wanted to demonstrate what a huge truck-mounted tree spade could do. When radiant heat became a thing in the early 1990s, Russ installed a warm-water pipe system in his driveway for snow-melting, trying out a new macadam containing recycled plastic at the same time. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, he never uses it because it consumes too much natural gas to heat the water.) When This Old House featured new energy-efficient windows with a heat-reflecting membrane suspended inside their thermal panes, he decided to install some in his Nantucket vacation home to test them. (He grimly reported later that their seals failed.) On the day of my visit, he was rebuilding a garage door whose composite bottom panels had rotted away, lamenting the way companies use “these new materials that have been tested in some lab for a couple of months.”

The Morash living room sits in the rear addition they put on in 1974. Light-filled even on a gray day, it looks out over the landscaped backyard, garden beds in the distance. It’s hard to miss the golden glow of the 14 Emmy statues in this room (Russ has another one, a prestigious Lifetime Achievement Emmy, out on Nantucket). Nearby stands Sam, a life-size cigar-chomping carved-wood cowboy with a stubble of nails. The house is tastefully replete with mementoes and antiques they’ve collected during the travels the show made possible—they picked Sam up during the This Old House project in Santa Fe. And everywhere are the works of Norm Abram. He made 236 projects during The New Yankee Workshop’s 21-season run, and most of them required a practice-run prototype.

“We just kept replacing our old furniture with these beautiful pieces,” marvels Russ. “How fortunate we are to live with this stuff.”

There are high-style examples, like the exquisite tiger-maple highboy modeled on an original built in Connecticut in the early 19th century, and simpler pieces, like a three-legged Shaker candle stand in cherry. None escapes Russ’s wondering, wandering eye; he flips the candle stand to point out the triple through-dovetail joint holding the legs in place.

“You notice how there’s no wobble? There are no screws or nails holding it together. It’s perfect,” he says admiringly, “in all ways.”

For many years Saturday mornings were dedicated to This Old House, The Victory Garden and The New Yankee Workshop. Russell Morash was the Master of DIY television. RIP Mr. Morash.