The Most Famous Fish Shack in the World | First Light

Behind its picturesque facade, this little red building in Rockport, Massachusetts, holds meaning and memories.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Stephen Sheffield

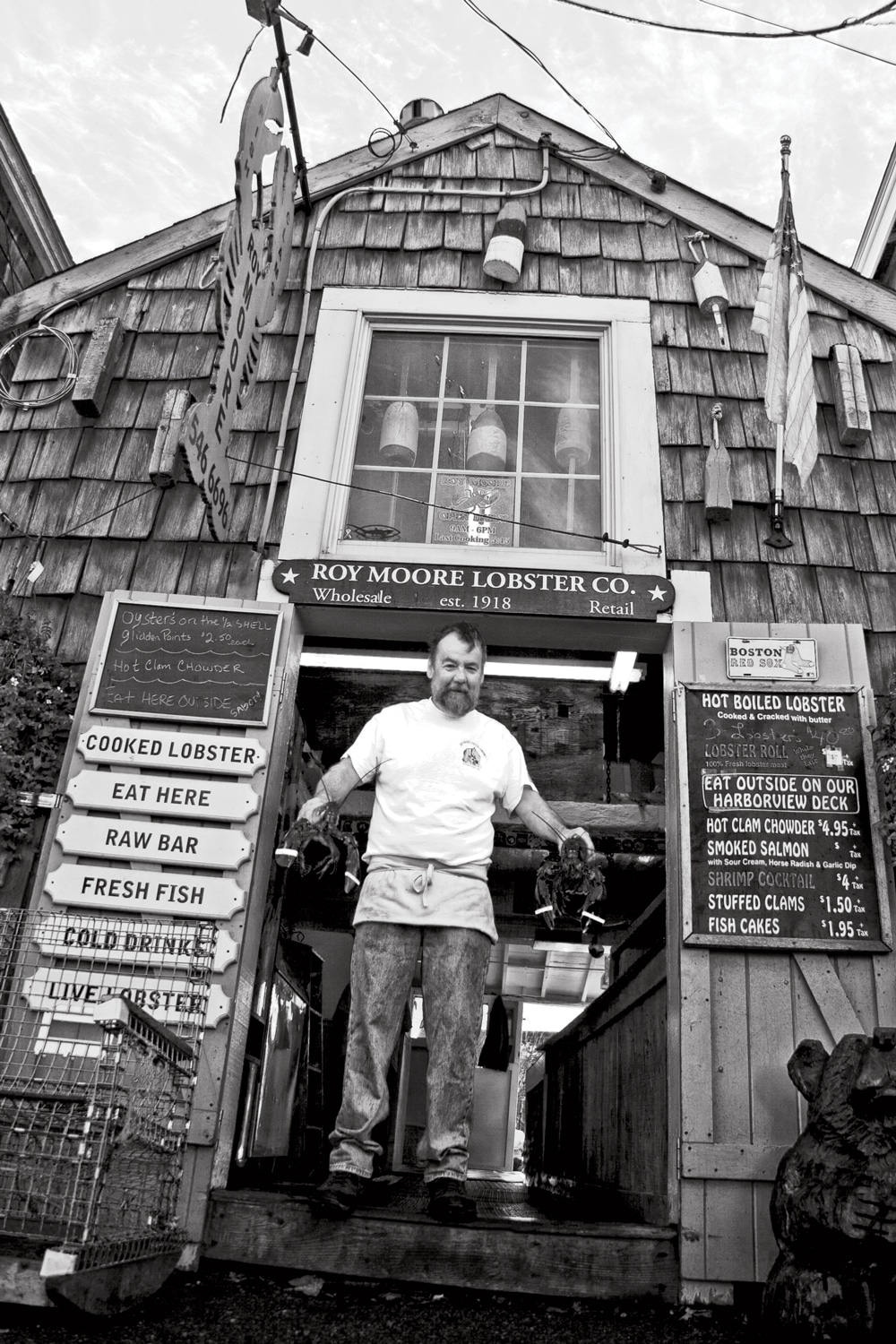

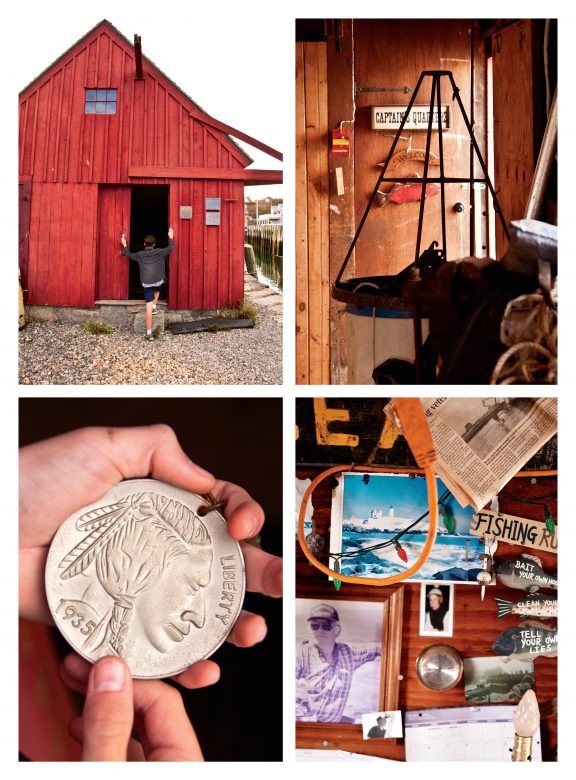

I’m standing on an apron of stones at the entrance to Motif No. 1, the famed landmark in Rockport, Massachusetts, on a brilliantly sunny day—this rectangle of red against a wall of blue. Next to me is Kenny Porter, a boyhood friend who owns neighboring Roy Moore Lobster Co., and who has offered to take me inside. “Pretty elaborate security system, right?” he chuckles. There’s a rusted old chain casually draped over the door hasp, but no lock. A large solitary granite cobblestone is a makeshift, off-center step at the door’s threshold. Three plaques are affixed to the red siding, but one is badly weathered and impossible to read. Instead it’s hand-etched with a scratchy “Motif 1” that looks like the product of a late-night misadventure. It’s surprisingly endearing to see our picture-perfect building so clearly not.

Photo Credit : Stephen Sheffield

To my left, across a narrow channel of water, is the pier where my 20-something artist dad once ran a frame shop, his meager income nicely supplemented in a dry town by selling cold beer out the back door. He and my mom would settle in Rockport a few years later, meaning I’d grow up here, on an island in everything but the name, attracted and repelled by the fish shack that makes my town a little bit famous. In getting to go inside for the first time, however, I’m definitely attracted. I don’t know anyone from Rockport who’d feel any differently. The exterior of the building is identifiable around the world. The interior is ours.

—

Before finding Kenny, I take a walk through Dock Square to the alleyway next to the Judi Rotenberg Studio. It yields the money shot of the Motif, the long, narrow alley framing the shack a few hundred yards of inner-harbor water away. A woman is at the water’s edge, staring dreamily out at the Motif, just as I expected someone would be. I’ve seen the Motif thousands of times and will likely see it a thousand more, and still I snap a picture.

It is difficult to pinpoint why people fall for Motif No. 1—as Kenny says, there are lots of fish shacks in Rockport—but I’m looking, too, and there is something perfectly proportioned and pleasing about the building and how it sits on the pier in relation to everything else in the harbor. It’s not trying too hard, but it’s a scene-stealer all the same. We don’t stare at it as the visitor does, yet I think we’re satisfied to know it’s there.

A lone painter, plopped down on his fanny along the Bradley Wharf entrance road, has nothing more to encumber him than a light jacket, a bottle of water, and a sketch pad. A retired architect from Houston, Tom Fannin is doing a watercolor of the Motif—but not representationally, he adds. His stroke feels better outside, freer en plein air, he tells me, though a “few more clouds would make it more fun.” It’s a too-perfect day.

“Free” wasn’t the dominant sensation of some other plein air painters I met on an earlier May weekend. They’d gathered on Motif No. 1 Day, an annual celebration featuring a road race, live music, and vendors in Harvey Park. At the invitation of the Rockport Art Colony, local artists were encouraged to take their best shot at Motif No. 1 and exhibit the results in the afternoon. Organizer Dan DeLouise was happy with the turnout that morning, with a half dozen painters in position—the year before, there’d been only him and one other—but there was angst with the burdensome air of expectation. The canvases were small. “What else can you say?” muttered one woman, who’d found a hard-earned midmorning spot between a Toyota sedan and a Silverado. (“Please don’t hit the easel,” she intoned to a departing motorist.)

I could empathize. What else can you say about a building whose story is told in books and innumerable travel articles? And yet, when I sent out word among old friends that I was writing about Motif No. 1, I heard fresh stories.

One of my favorites is my friend Kip’s. He got elected to a statewide program in high school, and as he prepared to go and meet his new roommate from the western part of the state, he looked for an object that would say something about where he was from. He decided on a large, jagged piece of wood. It was from the Motif—the original one that was destroyed by the Blizzard of ’78. Like a lot of people in town, Kip hoarded pieces of the broken shack “as if they were moon rocks.” Kip said his roommate’s reaction was priceless: “What is that?” In that moment, he knew the kid couldn’t possibly understand. Kip himself barely did. So he mumbled something about an ongoing woodworking project and tucked the offering back into his luggage.

Sometimes we forget that as much as the building has been painted, photographed, and reproduced on all manner of curios, it isn’t as famous as we assume. Everyone has seen it, but that doesn’t mean they know what it is. Or what it means.

Photo Credit : Stephen Sheffield

Back in the 1930s, it was a fish shack like many others in the harbor. The town now owns the building, but it didn’t then. It was nameless. It was, however, prominently placed downtown, just down the hill from the Rockport Art Association. It was an easy target for Lester Hornby’s art students. As legend has it, the master teacher (who’d lived and painted in Paris for years) gave the much-painted building the moniker Motif No. 1.

The story that resonates with locals, however, is the one about how artists and townspeople built a 27-foot scale model of the Motif as a float and drove it 1,000 miles to the American Legion Convention at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. The float, which earned a top prize, effectively began the era of Motif notoriety.

Replicas are still being built. On a recent visit to the locally owned lumberyard, I bumped into a half-finished chicken coop made in the likeness of Motif No. 1. The builder, Todd Smith, the son of the yard’s owner, couldn’t say what exactly inspired him, only that he was pretty happy with the way it was going. “People are going to be knocking at your door for one of those,” said the yard supervisor. It was the perfect Rockport marriage of form and function.

Part of the Motif’s legacy is how we say the word. “If you’re local you say mo-tiff,” says Kenny, “but if you’re from out of town you say mo-teef.” Yet it’s more complicated than that. If you’re from the working-class part of town, what old-timers call the North Village or Pigeon Cove—the place where the granite was mined and the Rockport Tool Company pounded away—the mo-tiff pronunciation is more common. The red building is how we self-identify. Local. Or a little more local.

It’s also how others identify themselves. “It’s my signature—I sell it everywhere,” says Janis Anderson, when I ask her about the unusual photograph of the Motif she has on her easel at a street arts festival in Beverly. The image, with its unlikely overlaid vertical reflections of the inner harbor and the Congregational church in the distance, seems to be ingeniously manipulated, but she says it was a singular moment granted to her, when light and luck smiled. There was no trickery, just magic; she was set up on T-Wharf at the right time. It’s her Mona Lisa, and though I’m harmless enough with a smartphone, she refuses my request to take their picture together.

My friend Dana’s postal service route covers Bradley Wharf. He sees the Motif nearly every day. His favorite story is about that “rare moment of municipal brilliance” in 1977, when the town had blueprints made for the exact dimensions of the Motif. A year later it was wrecked in the blizzard. Thanks to those plans, the present-day “Motif No. 2” (inside joke) was born “through public effort and subscription,” erected and dedicated in November 1978.

In the Academy Award–winning film Finding Nemo, writer-director Andrew Stanton (Rockport High School Class of ’84) placed a painting of the Motif in a dentist’s office. Musician Nelson Bragg (Class of ’79) has it on the cover of his album Day Into Night. Icons populate the digital landscape. For Rockport expats it’s a running gag; it’s a flag in the sand.

—

The closer you are to the Motif, the messier it gets. The unmoored stepstone, the plaque with the childlike scrawl, the missing (or simply unnecessary) lock. But these aren’t blemishes, really—they’re signs of life, of a quirky, full-featured place. Inside the building is more of the same: open storage stalls for a few fishermen and the harbormaster. It’s comforting that, inside, the Motif looks like any other fish shack.

But as Kenny has promised, the best is yet to come. On the second floor we pop into a treasure-filled attic from our childhood imaginations. There are layers upon layers of odd collectibles and yellowed news clippings. On a joist over our heads is a five-foot-long bill of a prize swordfish. Of course! Next to that, on the adjoining joist and getting equal billing, is a tenor saxophone. A sextant is cheek by jowl with a disco ball. It’s like that throughout, in part due to the tenant, a marine salvage operator and colorful harbor mainstay named Billy Lee. He’s not here today to explain the ceramic toucan or the cubist painting reprint or the saxophone, but no matter.

Kenny is overdue back at his bustling shop, but he’s happily losing himself in the buoys and belongings of fishermen he’s known, and vintage paintings, woodcuts, and photographs of the building we’re in. “It’s too bad, these are getting ruined—I hate it!” he says, alarmed at their dissolving condition. “But you don’t want to take them out of their spots.” It feels like a sacred space, as if we’re on an archaeological site, which we kind of are. There’s a ship’s bell and a tidy cast-iron stove. For a long time we hover over a small mounted photo: The handsome young fisherman on the right was a classmate of ours who died soon after the picture was taken.

The building teems with stories. Our stories. When we get back outside, I ask Kenny if he owns a painting of the Motif. Kenny has a robust art collection, one that’s so large he’s not sure of everything he’s got, but nothing immediately comes to mind. He professes no special sentimentality about the building in his backyard. What about a salvaged piece of wood from the original Motif? Did he get himself a keepsake? “Oh, I think I do have one of those,” he says. “Oh, sure.”

I cant wait to visitRockport this summer.

I learned to swim off the wharf and as young kids, Roy Moore used to give us bags of cooked lobster bodies that we would take up to the breakwater and play hide and seek in the rocks and eat lobster.

The chicken coop is finished and the young man’s name is Ben, a true son of Rockport.

My husband and I have come to this area and stay at the Cape Ann Motor Inn every year… Since 1971, our 48th anniversary this year!

We visit every year! One of my favorite coastal towns! Check out Halibut Point..such a hidden Gem!

I was born, raised and still live an hour from Gloucester and never have I called it mo-“tiff.”

My mother, Mary O’Leary painted Motif #1 back in the 1970s. She was a member of the North Shore Art society back in the day. I have many memories of trips from Lexington to Rockport. Enjoy my mother’s painting every day

Wish you could put a picture of her of her painting here!

wonderful visit to Rockport vicariously. Thanks.