Peabody Essex Museum’s Gripping New Exhibition Shines a Spotlight on Salem Witch Trials

Drawing on rarely seen items from the sprawling collection of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, “The Salem Witch Trials 1692” tells the tragic, true stories behind one of New England’s most notorious events.

PEM’s exhibit includes two of T.H. Matteson’s famous depictions of the crisis. In this 1855 oil painting, “The Trial of George Jacobs” we see a scene from the famous court case in which Jacobs’ own granddaughter accuses him of witchcraft.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of PEMSponsored by the Peabody Essex Museum

In mid-September 1692, Mary Esty made a final, emotional appeal for her life to be spared. The wife of a wealthy farmer in Topsfield, Massachusetts, the 58-year-old mother of 11 had weathered a harrowing spring and summer. Since the early part of the year, her community, along with others in and around the town of Salem, had been roiled by a series of witch trials that threatened the very core of the Massachusetts colony. Families and friendships had been ripped apart in a crisis that eventually involved more than 400 people and led to the deaths of 25 innocent men, women, and children.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of PEM

Esty and her family were at the center of the madness. One of her older sisters, Rebecca Nurse, had already been tried and convicted for witchcraft; she was hanged in July of 1692. A younger sister was also charged with the crime, and even Esty’s mother was under suspicion. Esty herself had submitted to arrest in April and was sentenced to death in early September.

In a carefully worded petition she filed only a week before her execution, Esty pleaded with newly appointed Governor William Phips, the court, and the clergy to reconsider not just her conviction but also the trials themselves. “I petition to your honors, not for my own life, for I know I must die,” she wrote. “And my appointed time is set. But the Lord, he knows it is, that if it be possible, no more innocent blood may be shed.”

That powerful document, along with a host of other rare papers and relics associated with this period in colonial Massachusetts, is now on display at the Peabody Essex Museum as part of its newest exhibit, “The Salem Witch Trials 1692,” which runs through April 4, 2021. The exhibit showcases a curated selection of PEM’s collection of witch trial materials, which is the largest such collection in the world but has rarely been on public view.

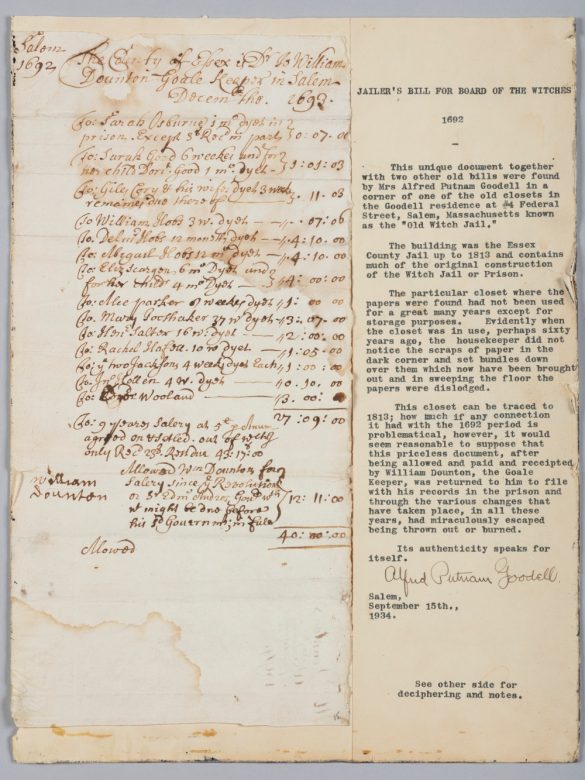

Included in the exhibit is the execution warrant for Bridget Bishop, the first of 19 people to be hanged in the Salem trials; invoices from the jailer; and direct testimony from accusers. Adding context to such documents are rare books such as Malleus Maleficarum, a 15th-century guide to finding and executing witches that was recently acquired by PEM’s Phillips Library.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of PEM

This is not an exhibit that merely displays what PEM has in its collection, however. Instead, it’s a tightly constructed and personal journey into the witch trials and the lives of those who survived them, presented in five thematic, roughly chronological sections: “Witchcraft from Europe,” “Salem and Early New England,” “Intolerance and Suspicion,” “Reflection and Impact,” and “Reckoning and Reflection.”

Along with the documents, visitors will see personal possessions of those involved in the trials, such as a trunk that belonged to a judge named Jonathan Corwin, who resided at the 17th-century house in Salem that is today known as the Witch House. There are also two original beams from the Salem jail and an 1855 painting from PEM’s collection, Tompkins Harrison Matteson’s Trial of George Jacobs, Sr. for Witchcraft, that details the pandemonium in the courtroom as the drama unfolds, as George Jacob Sr.’s own granddaughter points an accusing finger.

“My hope is that visitors will encounter these original witch trial documents and objects and recognize that there were real people that are at the heart of this historical drama,” says Dan Lipcan, head librarian at PEM’s Phillips Library. Along with Lipcan, the exhibition’s curatorial team includes Dean Lahikainen, the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Art; Paula Richter, curator for exhibitions and research; and Hilary Streifer, assistant manuscript librarian at Phillips Library. “The victims of the Salem witch trials had complex emotions, fears, and doubts just like we do,” Lipcan adds. “To empathize and understand their experience emboldens us to speak out against injustice and cruelty in our own time.”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of PEM

The context for the witch trials begins with what came before. Witchcraft hysteria had gripped much Europe since the 15th century. During the great age of witch hunts, from 1400 to 1775, religious upheaval and warfare, political tensions, and economic dislocation led to waves of persecutions and scapegoating in Europe and its colonies. In all, roughly 100,000 people were tried for witchcraft and some 50,000 were executed.

“The Salem Witch Trials 1692” carefully walks PEM visitors through this early history while also detailing the challenges that the colonists faced — from extreme weather to the threat of constant war to a series of crop failures — that fueled a sense that allies of the devil lived among them.

“There was really this perfect storm of events that made people feel unsafe,” says Emerson W. “Tad” Baker, vice provost and history professor at Salem State University, who consulted on the exhibit along with Richard Trask of the Danvers Archival Center, at the Peabody Institute Library of Danvers, and Kerry Anne Morgan, director of gallery and exhibition programs at Minneapolis College of Art and Design. “If you don’t feel safe and you don’t feel secure, then you start looking at people to blame your problems on. That is when the scapegoating begins.”

Photo Credit : Peabody Essex Museum

“The Salem Witch Trials 1692” marks the first time in nearly three decades that artifacts from PEM’s vast witch trials collection have been put on display. The exhibit was born from an initiative of PEM’s director and CEO, Brian Kennedy, to give greater Salem a stronger presence at the museum — something that’s also reflected in the companion exhibit “Salem Stories.” Open now and continuing through October 3, 2021, “Salem Stories” uses more than 100 works, including paintings, sculpture and textiles, to bring Salem’s history to life, from past to present day.

Photo Credit : Kathy Tarantola/PEM

Taken together, the two exhibits show how far the city has come in telling its story authentically. It wasn’t until 1703 that Massachusetts begin issuing pardons for victims of the witch trials, a process that wasn’t completed until 2001. Shame over the trials became so ingrained that it took 300 years before a memorial to the victims was constructed — which is why the most moving part of “The Salem Witch Trials 1692” comes at the end, where a wall reminiscent of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington lists the names of the victims by the date they died. It’s final, somber reminder of the human toll of this event.

“In 1692 we made the mistake of prejudging people and rushing to judgement,” says Baker, author of the 2015 book A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Witch Trials and the American Experience. “Today, I think the city really prides itself on welcoming everybody because of what happened. So I hope when people come to Salem and take in the wonderful history, the PEM, the culture, and the architecture, they’ll be able to have a more serious reflection on what this period all means.”

The Peabody Essex Museum is located at East India Square, 161 Essex St., Salem, MA. It is currently open from 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Thursdays through Sundays. Reserve tickets in advance atpem.org/ticketsor by calling 978-542-1511. For details on PEM’s safety protocols, go to pem.org/safety. To listen to a riveting podcast episode about the Salem Witch Trials, got to pem.org/pemcast

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich