Maritime Salem, Massachusetts | A Visit to the Peabody Essex Museum and Salem Harbor

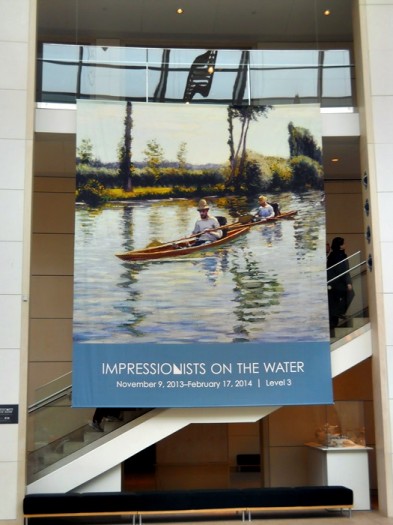

It appears art has fused with the sea in Salem, Massachusetts. The Peabody-Essex Museum’s newest exhibit Impressionists on the Water, open through February 17, 2014, has found a proper setting in maritime Salem. This past rainy Sunday, I spent the day discovering the maritime influence in Salem’s art and culture. The exhibit opens with a […]

A tour group stands in the cold air.

Photo Credit : Zinnia SmithIt appears art has fused with the sea in Salem, Massachusetts. The Peabody-Essex Museum’s newest exhibit Impressionists on the Water, open through February 17, 2014, has found a proper setting in maritime Salem.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

This past rainy Sunday, I spent the day discovering the maritime influence in Salem’s art and culture. The exhibit opens with a stunning Monet painting placed next to a model sailboat. The clear connection between the subject of the Impressionists and the model ships displayed the surprising theme: an acknowledgment that the placid subjects of the paintings come from a rich history of man and boating.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

The exhibit retells the maritime history of France, starting with its trade in the 18th and 19th century. A French Naval Frigate Model from the 1780s is placed next to a painting by Francois Joseph Frederic Roux, Fleet Maneuvers (French Warship) from 1834. Both are beautiful recreations of an intricate ship, but hold a high regard for the dramatic.

As I moved through the gallery, I was led into the sporting life of the Impressionists and boating. The turmoil of the romantic fleets and ships eventually shifts into the relaxed and recreational boats of the Impressionists. Dark and rolling clouds of benevolent storms are replaced with white, billowy skies. The models of trade and warships are replaced with full-sized skulls with names like the Nana.

The whole exhibit is designed around the boating experience. Boat curves and details subtly appear on the walls of the exhibit space. Cloud projections are set up on the light grey walls. Perhaps the most rewarding live-action feature of the exhibit is the replication of Monet’s floating studio he had in Argenteuil. You stand inside this “boat” with cast-iron pans, paintbrushes, and breakfast’s leftovers. You look upon a video screen with alternating river scenes. Next to this “window” is the artist’s window: an electronic canvas that records the creation of pastel landscapes.

My grandmother, who accompanied me to the museum, was perhaps critical of the “formless sails” and “curly-haired heads” of Monet’s rolling waves. Still by the end the emerald greens, soft or stormy grays, and Renoir’s peachy pallet came to be approved. She was quiet pleased with the exhibit.

Impressionist on the Water is scattered with French flags, but the story depicted by the artists is a similar narration to Salem’s history. With the original settlement in 1626, Salem fishermen developed an economic base that would develop into the international trading port of Salem. Even the PEM’s roots trace back to the sea. The museum started in 1799 when the East India Marine Society of Salem’s captains decided to collect their worldly objects.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

The rest of maritime Salem is just outside the museum’s doors with the National Park Service’s visitor center across the street. My family and I took a short drive to see the historic wharfs that are a part of the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, and to grab lunch.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

It was nothing but a pleasure to discover how the sea has impacted Salem’s cuisine. We went to Finz for a late lunch. The restaurant sits right on the water. Their menu ranges from classic New England seafood like lobster rolls, to creative seafood dishes like buffalo calamari.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

After lunch, I took a quick walk down the wharfs. A tour group was stopped by the historic houses, and a few people were walking with their dogs on the windy wharf.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Despite the cold air, the scene resonated with the exhibit at the PEM. Gulls flew from the harbor and boats lined the docks. A small yacht named My Wife had the same humor of painter Gustave Caillebotte’s boat, the Roastbeef.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

The Friendship, a replica of the trading ship built in 1797, sits in the wharf with the backdrop of Salem’s mills and harbor. The New England scene could have been a replica of Monet’s Sailboats on the Seine, which subtly captured industrialism on the French rivers.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

At the same time, nothing about Salem could have been a part of those French paintings. From the federal-style houses, to the seafood, the Christmas lights in the stores, and the cold November day; it was New England through and through.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

It was such an easy and enriching day trip. As the weather gets colder and wetter, looking out through the museum windows can be quiet a comfort.

Photo Credit : Zinnia Smith

Walking with my grandmother from the restaurant to the car, she pointed to the historical wharfs of Salem and restated everything I had noticed from my walk, and proceeded to instruct me to bring my watercolors and easel down here to the harbor. I responded that I would need to bring a large hat and mittens.