How Boston Got Its Christmas Tree | Holiday History

Every year Nova Scotia donates a Christmas tree to the city of Boston as a thank you for their aid following a 1917 tragedy. It’s a fascinating story.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanBy the time I saw the Tree again, two weeks and more than 700 miles distant from where I first made its acquaintance, I felt as though I knew it better than almost anyone else in the crowd gathered here on Boston Common to greet it.

On a mid-November day last year, I had driven along a two-lane blacktop in the heavily wooded town of Ainslie Glen, on Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton, following a local’s tip that I should stop “where you see some cars parked.” I saw some cars, all right—I parked on the shoulder, the last in a string of a good mile of them, and walked to where the road was blocked off by men in orange safety vests. There was a truck with a crane, and a big flatbed semi. In a roadside clearing stood a crowd of schoolchildren, all wearing toques in the blue and white of Nova Scotia and waving little provincial flags. Hundreds of their elders milled around with an air of cheerful anticipation.

And there, down a short slope from the roadside, stood the Tree.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

It was a white spruce, 66 years old and 47 feet tall, grown straight as a schooner mast. Its branches were tied tight against its trunk, and not a needle was out of place. It was an especially significant tree this year, as it was the first in its long ceremonial line to come from Cape Breton, and unusual for its having grown on public land. Private landowners clamor each year for their trees to reach this pinnacle of honor, and scouts from the provincial Ministry of Natural Resources fan out to see whose spruce might measure up.

There were speeches, one in a lilting Scottish Gaelic appropriate to a district where the road signs are bilingual; Ainslie Glen, I’d noticed, is Gleann nam Màgan. A kilted bagpiper played. And since this was the territory of the Waycobah Mi’kmaq First Nation, there was drumming by the group We’koqma’gewiska, a speech by Mi’kmaq Chief Rod Googoo, and a traditional ceremony in which Mi’kmaq representative Kalolin Googoo held a smoking dish of tobacco while John Cremo, a member of the nation’s grand council, circled the tree, reverently laying his hands upon its trunk.

Then a Cape Breton fiddler struck up “Here Comes Santa Claus” as the jolly old elf himself strode through the crowd. Santa had a job to do. A crane carried him and an assistant to the top of the tree, where they tethered the big spruce to the crane so that it wouldn’t slam to the ground when the time came.

And the time came next. Firing up a big Husqvarna chainsaw, a forester surgically cut the tree a yard or so above the ground. It swung loose for a moment, then it was gently lowered onto the flatbed trailer.

Moments before, the Nova Scotia minister of natural resources, Lloyd Hines, had said, “We will never forget the kindness bestowed by Bostonians—they were there for us when we needed them.” And the flatbed carried a big blue sign: “The Nova Scotia Tree for Boston.”

* * * * *

A century ago, it was another Nova Scotia morning on the cusp of winter. The port of Halifax bustled with the maritime business of the Great War. Ship after ship steamed into one of the world’s greatest natural harbors, where convoys assembled to carry men, munitions, and matériel to the insatiable Western Front.

The French ship Mont Blanc had left New York on December 1, 1917, laden with nearly half a million pounds of TNT and 2,300 tons of picric acid, the explosive used in artillery shells. Lashed to the deck were steel barrels containing benzole, a highly flammable cocktail of benzene and toluene. The Mont Blanc approached Halifax Harbor on the evening of December 5, too late to steam beyond the antisubmarine nets that were lowered across the harbor entrance each evening. It would have to wait until morning to pass into the Narrows, the slim channel lined with the city’s dockyards, and head into broad, protected Bedford Basin, where transatlantic convoys were assembled.

As the Mont Blanc’s pilot gingerly navigated the Narrows on the morning of December 6, another ship, the Imo, was steaming out of Bedford Basin with a cargo of civilian-relief supplies for war-ravaged Belgium. Port side to port side—that was and is the rule for vessels passing each other. But this morning the rule was not followed (courts of inquiry first assigned blame to the Mont Blanc, then to both ships), and the two vessels began a slow dance similar to what happens when two people feint and dodge in a hallway to avoid collision.

The feints and dodges didn’t work, and the dance became one of death. At 8:40 a.m., the Imo’s prow sliced into the starboard bow of the Mont Blanc, rupturing barrels of benzole and showering them with sparks.

The crew of the Mont Blanc knew the nature of their cargo, and as flames and smoke billowed higher they abandoned ship, rowed madly to shore at Dartmouth, the town opposite Halifax, and took cover in a grove of trees. But almost no one in Halifax knew what the burning ship carried, and there was little cover to be taken even if they had. Most vulnerable, as the fire ate deeper into the Mont Blanc’s hold, was the working-class Richmond neighborhood in the city’s North End. Here, as Hugh MacLennan wrote in Barometer Rising, a novel set amid the events of that terrible day, “the wooden houses crowded each other like packing-boxes left out in the weather for years.”

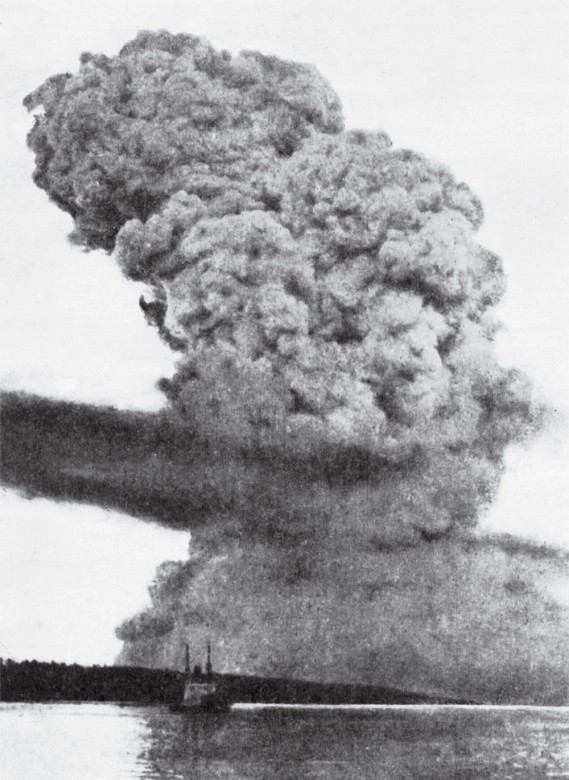

Photo Credit : Library and Archives, Canada

At 9:06 a.m., the heat of the benzole fire ignited the Mont Blanc’s hellish cargo. Within a 50th of a second, the vessel disappeared in a cataclysm ranked as the world’s most powerful man-made explosion until the bombing of Hiroshima almost 30 years later. The granite floor of the Narrows cracked open. Windows shattered 60 miles away. A tidal wave billowed outward with such force that a ship’s captain far out at sea thought he had struck a mine. A 1,140-pound piece of the Mont Blanc’s anchor landed two miles away. And most of the Richmond neighborhood, along with much of the rest of Halifax east of its massive hilltop Citadel, simply ceased to exist.

A square mile of the city was totally destroyed. Some 1,650 people died instantly; 9,000 were injured, many blinded by flying shards of window glass. Nearly 1,750 buildings were flattened, including three schools, and overturned coal stoves quickly spread conflagration through the wreckage. Twelve thousand other buildings were damaged. In a city with a population of fewer than 60,000, the eventual death toll reached at least 2,000.

That night the temperature plunged to near zero, and a daylong blizzard began to drop 16 inches of snow on the smoldering ruins of Halifax.

Halifax resident Eugenie “Genie” Fox heard firsthand about that terrible day from her grandmother, Catherine McNeil. “She was home on Barrington Street with her four children, doing housework, getting the two older kids ready for school. Her husband was at sea, serving with the Canadian navy,” Fox recounts. “Her neighborhood, pretty much the whole North End, was flattened.”

Yet the McNeil house remained standing. “It was just a fluke that my grandmother’s house survived when others around it were leveled,” says Fox. “Many of her friends and neighbors were killed.” Among those who survived was 2-year-old Anne Welsh, who was thrown into a pan of warm ashes beneath a kitchen stove. Rescuers found her there, insulated from the cold by the ashes, more than a day later. “For the rest of her life,” Fox recalls, “she was known as Ashpan Annie.” Like Catherine McNeil, Anne Welsh lived into her nineties—but her mother and brother died on that December 6.

Like many women in the aftermath of the explosion, McNeil took in sailors as boarders, as protection from looters. “The sailors needed housing, too,” says Fox, “since many of their barracks had been destroyed.”

Photo Credit : Riley Smith

* * * * *

The telegraph lines serving Halifax were severed in the blast. So it was that the most important message of the day, addressed to the city’s mayor, sputtered into oblivion and went unanswered:

Understand your city in danger from explosion and conflagration. Reports only fragmentary. Massachusetts ready to go the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of. Wire

me immediately.

The sender was Samuel McCall, the governor of Massachusetts. Receiving no reply, he sent a follow-up wireless message, concluding with an offer “to send forward immediately a special train with surgeons, nurses, and other medical assistance.”

Still no response. McCall then sent a second wireless message:

Realizing that time is of the utmost importance we have not waited for your answer but have dispatched the train.

The train left Boston that night. On board were 13 doctors from the Massachusetts State Guard, including several surgeons; 10 nurses; and six Red Cross representatives. The cars were packed with supplies: pillows, gauze compresses, bandages, slings, ether. And four pints of brandy.

As it headed north and then swung to the southeast, through New Brunswick, the train picked up workers to help repair as many damaged Halifax homes as possible in the face of the winter weather. At each stop, additional details were patched into what was still a hearsay narrative. “When the train got to Saint John, New Brunswick,” says interpreter Jeanne Church of Halifax’s Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “they learned that there was hardly a window left in the city, so they sent for glaziers and glass.”

Photo Credit : Granger NYC

But a more immediate task loomed: The blizzard that shrouded the ruins of Halifax stalled the relief train between Amherst and Truro, Nova Scotia, forcing men to dig through the enormous drifts that blocked the rails. In the words of A.C. Ratshesky, the Massachusetts Public Safety Commission officer who led the mission, they “worked like Trojans” to free the locomotive and cars.

The train reached Halifax around 3 a.m. on December 8, less than 48 hours after the explosion. That evening, the first patients were received at an officers club that had been requisitioned and outfitted as a hospital.

The next day, a second train left Boston with more doctors, nurses, and equipment for a 500-bed hospital. Also on their way were the Calvin Austin and the Northland, steaming from Boston laden with building material, along with trucks and drivers. The construction supplies were the vanguard of a rebuilding effort that would eventually include the donation of nearly 2.5 million square feet of glass and 7.5 million board feet of lumber.

A Massachusetts-Halifax relief commission was organized with the goal of raising money not only for constructing new housing for Haligonians left homeless, but also for furnishing temporary apartments and, eventually, creating a new neighborhood of permanent residences to replace the vanished “packing-box” houses of the old North End. Even the Boston Symphony Orchestra joined the effort, giving a December 16 fund-raising concert featuring legendary violinist Fritz Kreisler.

Organizers of the Massachusetts-funded campaign boasted they would build “one apartment an hour,” and construction was well under way as the new year began. The temporary apartments that rose quickly on the Citadel football grounds rented to survivors for $7.50 a month for three rooms, $5 for two. Another group of temporary structures, christened the Governor McCall Apartments by grateful residents, rented four rooms for $12.

Photo Credit : State Library of Massachusetts

But “temporary” meant just that. In September 1918, work began on permanent housing in what became known as the Hydrostone neighborhood, after the newly developed compressed-cement building blocks used in construction. More than 300 homes were built, all facing tree-lined boulevards. “People originally rented there,” Genie Fox remembers. “They paid rent to the Halifax Relief Commission, but they were later given the opportunity to buy. My grandmother lived in the Hydrostone for 68 years.” Today designated a Canadian National Historic Site, the now-upscale neighborhood was originally furnished with contributions from the people of Massachusetts. Those pieces that survive are now treasured heirlooms.

And in December of 1918, as the Hydrostone homes were still rising, the province of Nova Scotia sent the city of Boston a thank-you gift of a Christmas tree.

* * * * *

On a brisk, sunny morning the day after the 2016 tree-cutting, a crowd gathered at the Grand Parade in the heart of Halifax. The onetime military parade ground faces St. Paul’s Anglican Church, built in 1750. It is the oldest structure in the city and a survivor of the explosion—but not without scars. High on a vestibule wall, an iron bar impaling the plaster is one of the last few relics of the Mont Blanc’s violent end.

The crowd had come to see off the Tree. The big white spruce from Ainslie Glen had just arrived from Cape Breton, and its proud driver, Dave MacFarlane, was set to take it on a much longer trip as the annual Christmas gift from the people of Nova Scotia to the people of Boston—the 46th such gift since the annual tradition began in 1971.

Photo Credit : Riley Smith

Photo Credit : Riley Smith

An honor guard of police and firefighters, as well as red-jacketed members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, stood by as Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil spoke of “the powerful moment when you stand on Boston Common and see the Nova Scotia tree,” and Halifax Mayor Mike Savage vowed to “remember the friendship that came out of that terrible day.” For his part, Boston Parks Commissioner Chris Cook brought a colloquial touch of the Hub to the proceedings, telling the crowd they had “a wicked good mayor.”

As this was the first Boston tree to have been cut on Cape Breton, a rock band from that remote and beautiful region played a set. To mark Ainslie Glen’s place in the territory of the Waycobah Mi’kmaq—and in remembrance of those lost when the force of the 1917 explosion struck a Mi’kmaq encampment on the Dartmouth side of the Narrows—the native drummers gave a reprise of their performance at the cutting. And all the while, a line of Haligonians snaked through the little park, waiting to sign a “book of thanks” to be presented to Boston along with the tree. Finally, Jim Stewart, president of the Nova Scotia Guild of Town Criers, wearing 18th-century regalia, proclaimed in a booming voice the reason for the departure of the Tree.

* * * * *

Two weeks later, Premier McNeil’s “powerful moment” arrived, as he and thousands of Bostonians awaited the lighting of the Tree on Boston Common. The Cape Breton rockers played again, introduced by the hosts of the live TV special that centers on the event each year. Amid the dignitaries and entertainers was driver Dave MacFarlane, who told the crowd that “from the day I get here, I look forward to next year.” And Ainslie Glen had its mention, no doubt for the first time ever on Boston television. Mayor Marty Walsh pressed a button, and the big white spruce suddenly sparkled.

I stood at that festive corner of the Common, the Park Street Church on my left and the now-familiar Tree just before me. At my back stood the Massachusetts State House, from which Governor McCall sent his first urgent offers of help to a deafened and isolated Halifax.

A day earlier, I’d ventured deep beneath that golden-domed building, to a room housing special collections of the Commonwealth’s archives. Here I was shown yellowing typescripts documenting the work done to relieve the suffering of Halifax. Among the papers are transcriptions of hundreds of letters of gratitude sent by explosion victims. There are poignant apologies for a lack of eloquence (“I much regret not having words to express”); thanks for the plainly practical (“for the beautiful and splendid piano … my only means of livelihood”); and, from the superintendent of an infants home, for simple things that made an unexpected difference (“such comfortable tables and chairs … [that] have in some cases changed bad tempers into good ones”). But perhaps the most touching and succinct thank-you was penned by a Mrs. Joseph Richardson, who wrote, “I hope the good people of Massachusetts will be rewarded for all their kindness to the many who suffered in the terrible disaster of December 6.”

Each year a handsome Christmas tree arrives, and, a century on, becomes a part of that reward.

I grew up hearing stories of the Halifax Explosion. My Father was an 11 year old boy living in Halifax. At the time of the explosion he was on his way to a store to do an errand for his Mother. The large explosion caused him to lose the few coins he was carrying. Coming from a large family where every cent mattered he worried he would be in trouble for losing the money. Thankfully no one in our family was hurt and their home only suffered very minor damage. The family moved to Massachusetts in 1922. Years later I read how generous the people of Boston were to the people of Halifax. I think the Christmas tree is a wonderful gift and remembrance of that time.

Halifax suffered so greatly from the 1917 explosion because it happened on a ship below the waterline. Water does not compress so the force of the exploding ship hull was transmitted directing to the shore. Much worse than a tidal wave, the solid blast of water striking communities was more like the hammer of a pile driver. When building the atomic bomb, the explosion was not tested underwater, instead in the sands of Nevada, because of the unimagined devastation experienced by Halifax.

Adding to Rob’s comments, I understand that the under-water nature of the horrific blast blew all the water out of the harbor exposing the bottom for an instant before it came rushing back.

For a more extensive telling of the Halifax explosion, read “Curse of the Narrows” by Laura MacDonald

my father was 7years old when he had gone to buy a bottle of milk atLogan’s Dairying New Glasgow.Having left the milk on the kitchen table ,he left for school.What he thought was the door slamming behind him was actually the sound of the Halifax explosion.

See the New Book, The Reward by Robert Burns on Amazon Books

My mother was 8 years old and lived near Halifax and always remember the story of this. She never wanted to miss watching the tree lighting on the TV.

Thank you for this terrible, but also heart-warming account of history. But I am Anne Anderson, Erik is the son to whom I sent a Yankee subscription as a gift. I sure hope he is also receiving these fascinating tips of New England history?!

Very very moving article it warms me to know how wonderful our humans can be, with all this hate going on in our politics this is what America is truly all about ????

One more incredible reason why I will never let my Yankee subscription lapse. How I treasure these precious historical recordings from my parents’ youth. Now living in the beautiful Berkshires, born and raised in Boston 74 years ago, my soul will forever be New England and Boston-bred.

This a beautiful story of mankind and how we survive helping one another. I love Yankee articles and all the history that otherwise we would not have known. Thanks Yankee.

One of the most moving stories is that of Vince Coleman; here is Wikipedia’s account:

The death toll could have been worse had it not been for the self-sacrifice of an Intercolonial Railway dispatcher, Patrick Vincent (Vince) Coleman, operating at the railyard about 230 metres (750 ft) from Pier 6, where the explosion occurred. He and his co-worker, William Lovett, learned of the dangerous cargo aboard the burning Mont-Blanc from a sailor and began to flee.

Coleman remembered that an incoming passenger train from Saint John, New Brunswick, was due to arrive at the railyard within minutes. He returned to his post alone and continued to send out urgent telegraph messages to stop the train. Several variations of the message have been reported, among them this from the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.”

Coleman’s message was responsible for bringing all incoming trains around Halifax to a halt. It was heard by other stations all along the Intercolonial Railway, helping railway officials to respond immediately. Passenger Train No. 10, the overnight train from Saint John, is believed to have heeded the warning and stopped a safe distance from the blast at Rockingham, saving the lives of about 300 railway passengers.

Coleman was killed at his post.